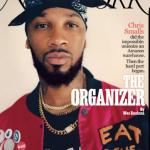

What Will Chris Smalls Do Next? He Did the Impossible: Unionize an Amazon Warehouse. Then the Hard Part Began

In early April, Chris Smalls drove down Canal Street, a blunt in his left hand and an iPhone in his right. He somehow juggled the steering wheel, too, guiding his boat-size Chevy Suburban through Saturday-evening traffic, glancing every so often over the wheel before looking back at the YouTube video playing on his phone. As the leader of the Amazon Labor Union, the first group in the country to successfully unionize an Amazon facility, he had been busy. He had already given two interviews that day, talked to a potential donor, and discussed renting an 11,000-square-foot space for the union’s headquarters. In recent days, he had fielded dozens of messages from workers across the country seeking advice about organizing their own Amazon warehouses as well as media requests from places like The Daily Show With Trevor Noah. “I’ve gotten messages like, ‘Yo, we need you to save the country’; ‘We need you to save gun laws’; ‘We need you to save abortion rights,’ ” he told me. “I’m the savior now of everything.”

Spending time with a 34-year-old whose to-do list is topped by “Save the world” had proved difficult, which is why I was riding around with him in his car — he was juggling me, too. Smalls stubbed out the blunt and turned up the volume on the YouTube video. The clip featured Jimmy Dore, the left-leaning comedian, talking about Smalls’s recent appearance on Tucker Carlson Tonight. Smalls was slammed on Twitter for appearing on the program, and he was annoyed by the suggestion that he was a pawn being played by Fox News. “Do people think there aren’t any Tucker Carlson fans who work at Amazon?” Smalls asked. “This isn’t about Democrats or Republicans, bro — it’s about workers.” Dore was making a similar point. “The video makes Christian Smalls look great,” Dore said. “I love the fact that he’s not wearing a shirt and tie and he’s just being radical.”

At that, Smalls smiled with satisfaction, his gold grills glinting. He was decked out in what he called “union drip”: Versace sunglasses, diamond earrings, chains coiled around his neck. The bling is a core part of his appeal and his politics. For working stiffs used to being bossed around by, well, their bosses, it epitomizes the belief that 40 hours of work a week should afford people more than just basic survival. It should buy a decent apartment, some savings, and maybe even jewel-encrusted fronts — Smalls’s version of bread and roses.

His fashion sense has spawned thousands of #UnionDrip hashtags and grabbed the attention of fashion designers and Hollywood. His image has also resonated with today’s blue-collar labor force, especially at Amazon, where the workforce skews young and three-quarters are Black and brown. His ALU is part of a burgeoning movement led by young workers instead of professional activists and without the support of traditional labor unions, whose bureaucratic professionalism and nonconfrontational tactics are considered by some to be stale and ineffective. Smalls calls this the “new school” labor movement, and he is its most visible practitioner. “They’re looking at me,” Smalls said of old-school unions like the SEIU, which he blames — along with Democrats — for abandoning low-wage workers and being too cozy with big business to rein in billionaires like Jeff Bezos. “If they was doing shit, they’d probably get some attention too. But they ain’t doing shit.” Switching to the third person, he said, “Chris is actually putting in the work.”

Smalls has been celebrated by everyone from President Joe Biden to Jesse Jackson as the prime author and strategist of what the New York Times called “one of the biggest victories for organized labor in a generation,” which came amid spiking rates of union activity across the country, with employees organizing at Starbucks, Trader Joe’s, REI, Activision, and Apple. But until he was fired in March 2020, Smalls was just another worker at the JFK8 fulfillment center in Staten Island, where he and 8,000 other employees packed up and shipped nearly every sex toy, phone charger, book, and roll of toilet paper that New York City residents ordered from Amazon.com. He formed the ALU in an audacious attempt to reform the second-largest private employer in America. Last year, Amazon spent $4.3 million on anti-union consultants; on the day of its victorious union vote, the ALU, then a ragtag group of 20 members, had just $3 left in its bank account.

Since then, Smalls’s task has been to prove that his union could replicate its first win. He dreams of organizing every Amazon facility in the U.S. — that’s hundreds of thousands of workers. As the ALU’s leader, it is Smalls’s job to use his charm and clout to raise funds, corral sympathetic politicians, attract new members, and put pressure on Amazon to capitulate to the union’s demands. By making himself as well known as possible, in other words, Smalls hopes to expand the size and power of his union. “It’s a lot of pressure,” he told me, “but my voice was meant for something bigger than packing up boxes in a warehouse.”

That project, however, has already run into setbacks. On May 2, a vote to unionize a Staten Island sorting warehouse, LDJ5, failed, arresting the ALU’s momentum. Amazon has brought a case before the National Labor Relations Board to have the victory at JFK8 thrown out in a trial that is expected to be decided in August. And as the ALU prepares for contract negotiations for JFK8 that could drag on for years, the organization has been mired in infighting stemming from the perception that Smalls is now too busy being a celebrity to join his comrades in the trenches. “He thinks everything is about Chris Smalls,” Most Daley, an ALU member, told me. “We’re supposed to be a worker-led union, and he ain’t a worker no more.”

Smalls bristles at the notion that he has abandoned the ALU, underscoring that the success of this union specifically and the new-school movement more broadly has so far been powered by his prominence — his celebrity serves the movement, he insists, not the other way around. He noted that his critics “wouldn’t last one fucking day in my shoes. You want to be on TV? You want to travel the country? You want to have the weight of the world on your shoulders? Sure, take it all.”

Helping millions of workers rise up against a new American oligopoly may be too much to expect of a single person. But as we drove down Canal Street on that bright day, just two weeks after the JFK8 vote and before the LDJ5 debacle, Smalls seemed to have no limits. He cranked the wheel of the Suburban and steered onto Mulberry Street, where he hoped to hit the bars. (The previous night, he partied nearby with Paperboy Prince until 3 a.m.) He slotted the giant SUV into an impossibly small parking space on Baxter Street, bumping the Saab in front of him to fit. Then he stepped into the street and slipped his arms into a red satin jacket. On its back was stitched in big blood-orange letters EAT THE RICH.

Picture Smalls in a tiny two-piece suit as a young boy in Hackensack, New Jersey, where he grew up, playing Martin Luther King Jr. in an elementary-school pageant and getting his first taste of the gravity of leadership. In middle school, Smalls was athletic, popular, a natural trendsetter. He introduced nameplate belts to his classmates, showing up one day with a big buckle reading CHRIS in bold letters. He and his best friend would play hooky and go to Harlem. “I just always had an infatuation with going to Harlem,” he said, “because Harlem was known as a city that had so much swag.”

He studied for his associate’s degree in music administration from the Institute of Audio Research in Manhattan and started rapping, trying to break into New York’s hip-hop scene. At age 19, he lived for a summer in his PT Cruiser on Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights while getting invites to VIP clubs and helping put on shows, including one with Meek Mill. “I was better than the people around me,” he told me, “and their careers were taking off, so I know I could’ve made it big.” One night in 2012, he visited a strip club and was thrilled that one of his tracks was being played on the sound system. He posted about it on his personal YouTube channel, celebrating that his song was “ALREADY BUMPING IN STRIP CLUBS!!!” He described himself as well on his way on the “grind to fame.”

“I’m Chris Smalls, big balls,” he rhymes on a track titled “Work.” “I’m a big dog, making big noise / I’mma get mine; bitch, get yours.” He also dreamed of a future in which he was “in the mall / Buying everything that I deserve,” as he raps on a different song, “My Time.”

“Chris was always into gold, wearing caps and colors,” said Gerald Bryson, a co-founder of the ALU. “But he wasn’t hood — he was just a normal guy and a hard worker.”

His dreams of rap stardom were quickly complicated by reality. By the time he was 22, he was married and had a child. To sustain his young family, he spent the next five years working grueling manual-labor gigs, loading trucks for FedEx and hauling huge crates for a grocery-distribution warehouse. Amazon was supposed to be a life-changing opportunity. The company’s warehouses were popping up all over to serve its rapidly expanding delivery service, and his mother, Dawn Smalls, an administrator at Beth Israel, saw an opening for a job.

In 2015, Smalls started as a “picker” at a brand-new Amazon distribution facility in Carteret, New Jersey. He was excited by the PlayStations in the break room. Accustomed to working fast and hard, he excelled as a picker, whose job is to race across warehouses and pluck items from shelves, then sort them in preparation for the workers who package them. He easily exceeded Amazon’s quota of 250 items per hour, and after seven months he was promoted to a process assistant, a sort of assistant manager who oversees and trains their own teams of pickers. “I loved the fact that I was being recognized for my work,” Smalls said. “I was excited, went above and beyond. I was really pro-Amazon.” (Amazon declined to respond to requests for comment.)

In August 2018, he transferred to the newly built JFK8, an 855,000-square-foot warehouse on a marsh in Staten Island. Three years after he was promoted to process assistant, his career at Amazon had stalled, and by then his marriage was dissolving, his debts had grown, and he was depressed. A mental-health counselor took him to small-claims court for owing $667. “I had sleepless nights all the time,” Smalls said. “I had a lot of bullshit that I had to battle. I had to battle depression. I had to battle loneliness.”

Smalls found common cause with a group of his co-workers who would later go on to form the ALU: Bryson, Derrick Palmer, and Jordan Flowers — half in jest, they called themselves “the Four Horsemen” — and another worker, Jason Anthony, a 28-year-old with Clark Kent frames who worked on Smalls’s team of pickers and at times earned so little that he lived in a Brooklyn SRO. According to Bryson, the friends would gather each Saturday to watch Knicks or Nets games and play dominoes. They bonded over clubbing, smoking weed, their families, and their frustrations at work. The oldest of them, Bryson, was middle-aged and preferred Donald Trump to Biden; the youngest, Flowers, was just 19. When they took him to a club for his 21st birthday, he wore sweatpants and the bouncer wouldn’t let him in.

Still committed to rising through the ranks at Amazon — and desperately trying to pay his child support — Smalls threw himself into the project of becoming a full manager. At the Staten Island facility, the quota had by now been raised from 250 to 400 items picked per hour — that’s less than nine seconds per item, or about 4,000 items in a ten-hour shift — and Smalls estimates he and his team had the highest rate in the building. “I wanted to be on their crew,” recalled Angelika Maldonado, a 27-year-old from Staten Island who began working at JFK8 in 2018. “They were always laughing and having a good time but also working really hard.”

In the four and a half years Smalls worked at Amazon, he applied for a promotion to manager over 50 times. Ruth Milkman, a professor at the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies, said the inability of Smalls and others to rise through the ranks was in part a function of the company’s business model, which relies on a high turnover of entry-level workers to keep wages down. Meanwhile, according to one 2019 report, employees in the main Staten Island warehouse “are injured more often than coal miners, waste collection workers, and other laborers.” And according to 2021 OSHA data, the serious-injury rate at Amazon is more than double the rate of non-Amazon workers in the warehouse industry. As a result, the average tenure of an Amazon warehouse worker is just eight months, and the company’s turnover rate in its warehouses is around 150 percent each year, more than two times the average turnover rate of American workers.

Minority workers are disproportionately harmed by all of this, critics believe. Although 75 percent of warehouse workers are Black or Latino, only 8 percent of executives are. Workers who have been fired after complaining about conditions have overwhelmingly been people of color or women, according to former Amazon executive Tim Bray, who characterized such firings as “designed to create a climate of fear.”

By March 2020, Smalls had accepted that he would never be promoted. His wages had topped out at about $40,000 a year. At only 31 years old, he had begun to suffer back spasms. He commuted over two hours each way from New Jersey to Staten Island. As an additional incentive to promote high worker turnover, Amazon offered employees a $5,000 bonus if they quit after five years, at which point they are prohibited from working for the company again. Smalls planned to take this buyout. “It didn’t matter what I did,” Smalls said. “I had no chance of a promotion at Amazon.”

But before he could accept the $5,000, the pandemic arrived in New York. That same month, as the city’s COVID death toll was rapidly rising, his bosses informed him that a co-worker with COVID had been in their midst two weeks prior — and not only had the supervisors failed to tell employees, they now urged Smalls to keep it a secret. (His account is backed up by witnesses present that day.) On March 25, Smalls, Palmer, and a handful of others walked into the general manager’s office and insisted the company close to clean the building and send workers home, with pay, for two weeks. A few days later, management told Smalls he needed to quarantine for two weeks. No one else was put on quarantine. Smalls started planning a protest.

He had never done anything like it before, but from the start, he had an intuitive sense of how to orchestrate the optics of the situation. He reached out to the New York Post and said hundreds of workers would be marching out of the JFK8 building that coming Monday, March 30. Smalls had checked the weather and planned the march for lunchtime because he knew that on a sunny day workers would be outside eating, so it would look as if they were part of the rally. He promised the media hundreds of “protesters,” and that’s what they saw.

Two hours after the protest peacefully ended, he received a phone call: He was being terminated for violating his quarantine. It turned out to be an enormous blunder on the company’s part.

In what is now an infamous memo, notes from a meeting including Bezos and Amazon general counsel David Zapolsky that outlined the company’s strategy to undermine the pro-testing employees were leaked to a Vice News reporter. Smalls is “not smart, or articulate,” Zapolsky wrote. “Make him the most interesting part of the story, and if possible make him the face of the entire union/organizing movement.”

At first, Smalls had no interest in forming a union. Instead, he wanted an organization more akin to Black Lives Matter or the Sunrise Movement, one that would be a group of workers from Amazon and other stakeholders engaging in boycotts, pickets, and protests, putting pressure on Amazon’s bottom line. He called his group the Congress of Essential Workers, or TCOEW, a first step toward what would evolve into the ALU.

Smalls worked with Attorney General Letitia James on a case against the company. He appeared on Dr. Phil and 60 Minutes and was invited to Zoom with Angela Davis. He studied The Autobiography of Malcolm X. “I’m not gonna say I’m the Second Coming of Malcolm X,” he said, “but there’s a lot of things that happened in his life that I can absolutely relate to.”

As a result of Smalls’s growing notoriety, he attracted others who had been waiting for someone just like him to come along. One of these people was Connor Spence, a mousy 26-year-old with a scraggly Lenin beard. By most accounts, it was Spence’s idea to try to unionize Amazon. When the Zapolsky memo was leaked, Spence was studying aviation at Mercer County Community College in New Jersey and working at an Amazon facility at night. He said he was radicalized simply by how miserable the work was, and only later did he get into reading Marx, Gramsci, and the popular labor organizer Jane McAlevey. “Someone like Chris is naturally going to be a beacon for people like me and people who think the same way,” he said. “We’re all going to flock to him.” He introduced himself to Smalls at a rally in Manhattan and pitched him on forming a union. Smalls gave him his number, and soon after that Spence moved to Staten Island, got a job at JFK8, and became an integral member of Smalls’s circle.

At every TCOEW meeting, Spence would introduce himself by saying, “I’m Connor, and I’m here to start a union at Amazon.” Smalls was skeptical. “What we do is protest,” he said. “That’s what we’re known for.” Smalls thought McAlevey’s ideas about a worker-led democratic movement that eschewed the rigid hierarchies of traditional unions were abstract, irrelevant. When Spence and Carolyn Steinhoff, another early member of TCOEW, signed Smalls up for a free, six-week online organizing class given by McAlevey, Smalls agreed to attend but never showed up. “ ‘She doesn’t know what it’s like to work at Amazon,’ ” Steinhoff recalled him saying. “ ‘What does she have to teach me?’ ”

Smalls did seek support from his mother, Dawn, who had been part of the SEIU 1199 union as an administrative hospital assistant at Beth Israel. She and Smalls are exceptionally close, and she attended most TCOEW meetings. She loudly defended Smalls when, in May 2020, two people working with TCOEW, Katherine Washington and Emilie Hoeper, accused him of being shady about how he had spent $43,000 in donations collected via GoFundMe. “We do not know whether or not Chris redistributed his money to workers, used it for business expenses, or kept the money for himself,” they later wrote in a letter they posted on social media.

Smalls, who was still unemployed at the time, admitted to me that he mostly survived off this GoFundMe account, which had been created for him by a supporter in Virginia and advertised as a fund to “support us Essential Workers.” While it wasn’t illegal, or necessarily unethical, for him to use GoFundMe money for whatever he wanted, Smalls had allegedly told the women he planned to file paperwork for TCOEW as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, but he never followed through. (Smalls denied he made this promise.)

Steinhoff told me she thought the financial accusations were unfair given that TCOEW would have ceased to exist if Smalls couldn’t feed and house himself. Still, she understood how his unreliable communication could anger those around him. “He could be arrogant,” she said. “He was not someone who would step aside and let others speak a lot.”

Bryson, the ALU co-founder, agreed that Smalls could be “caught up a little bit with himself,” but his supposed arrogance was inextricable from his confidence, and to most, he was a leader who inspired awe and trust. “There’s something about Chris that makes you want to impress him,” said Maldonado. After seeing a story about Smalls’s firing on the news, Brett Daniels, a blond 27-year-old from Arizona, quit his job at an Amazon facility in his home state and bought a one-way plane ticket to New York so he could work at JFK8, saying he wanted to be part of a “revolution” led by a Black working-class man. “I’d been waiting my whole life for something like this,” he said.

On a podcast Smalls started in January 2021, Issa Smalls World, he interviewed labor leaders, historians, community organizers, and activists. Over more than a dozen episodes, one can chart the evolution of his thinking more clearly than he’s willing to reveal in interviews, perhaps out of fear of coming off as too radical and thus alienating those Tucker Carlson viewers he’d like to bring into the new-school labor movement. During our drive in April, I spotted Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth — the classic Marxist psychoanalytic tract suggesting that only violence committed against colonial oppressors can restore the dignity of the colonized — peeking out of his bag in the back seat. When I asked him about it, he demurred and said he was just flipping through it.

As Smalls explained on his podcast, the defining feature of his young life was his father going to prison for murder, which happened shortly after he was born. “The way I remember my childhood was going to different prisons, Rikers Island, some of the worst prisons you can think of,” Smalls said. “And when he was released for the first time, we actually bonded, and we got a chance to spend time as a free man, and it was the greatest feeling.”

But his father was soon back in prison. “When they come out, ex-cons, they don’t set them up for success,” Smalls continued. “He literally got a job and tried to do the right thing,” but then “he got laid off after they did a background check.” In 2017, his father was imprisoned again, this time for armed robbery.

Smalls increasingly saw connections between his life and his father’s, even while criticizing many of the decisions his father had made. Both men had struggled to find decent employment, both were warehoused in anonymous facilities, and both were at the mercy of authorities who didn’t seem to care much about their lives. Capitalism and mass incarceration were the first “epidemics of this society,” Smalls said on Issa Smalls World. “He’s going through the same thing, and I just feel it. I feel all of that.”

The disappointments of Smalls’s life and a whirlwind of new influences were cohering into a worldview. Amazon’s unforgiving algorithms measuring worker productivity, the company’s high injury rates, and the racial dynamics between management and entry-level employees — all appeared to Smalls as part of the same system that had enabled slavery and the carceral state. When he thought back to a day when an Amazon supervisor had told him to “whip these pickers back in shape,” he shuddered with anger. He noted the historical resonances of the word pickers. Sure, they no longer picked cotton, but they still plucked goods for wealthy consumers who had no idea what kind of labor was required to deliver them so quickly and cheaply. “Amazon is definitely the new-day slavery,” Smalls reflected on the podcast. “Jeff Bezos is definitely an oppressor, definitely a slave master.”

In another episode, he interviewed Carl Rosen, president of the United Electrical Workers, a pioneering worker-led union with 40,000 members. Rosen explained how laborers in the 1930s steel industry had confronted a challenge similar to the one faced by employees hoping to unionize at Amazon today. The steel companies were so powerful and monopolistic, and the workforce so massive and disorganized, that traditional unions had basically given up on trying to recruit them — they didn’t have nearly enough staff or resources. Employees in those facilities instead did it themselves, and, in so doing, they were freed up to engage in the militant tactics, such as general strikes, that established unions and paid, professional organizers in the U.S. have typically shied away from. That’s what Amazon needed, the two men agreed: truck drivers, warehouse workers, manufacturing employees, all united against Jeff Bezos. “It’s them-and-us unionism,” Rosen told Smalls. “What some people call class-struggle unionism. You know which side you’re on, and you take that into account as you do your fights.”

“Amazing,” Smalls replied.

People describe Smalls’s ideology as a mix of narcissism and egalitarianism, of earnest solidarity and ego — “Chris-ism,” as one former ALU member described it to me. But the key to Smalls’s success is how well he grasps class-war unionism as a moral outlook as well as a strategy. When, on July 20, 2021, news broke that Bezos had flown to outer space on his private rocket, it provided the perfect opportunity for Smalls and the other organizers to bond with beleaguered Amazon employees by skewering the CEO as a feckless billionaire whose head was literally in the clouds. A year earlier, Smalls had demonstrated the same savvy when he had led a protest outside Bezos’s mansion in Washington, D.C., in which he set up a guillotine. (“I thought that was a little too crazy,” said Flowers.)

A visit to Bessemer, Alabama, in February 2021 finally convinced Smalls that a union was needed in Staten Island. In Bessemer, Amazon employees had invited the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union to help them organize. He couldn’t believe what he saw. He wanted to meet with local pickers, but RWDSU staff seemed uninterested in his help. “What the hell is this other union doing?” Smalls said to me. “We as Amazon workers know how to connect with other workers.”

Since the 1950s, the share of union members in the workforce has declined from 35 percent to just 10 percent. Most major unions have responded by consolidating their power in the few industries in which they have a foothold: highly skilled jobs like construction and public-sector jobs like teaching. They’ve largely abandoned everyone else, especially low-wage and so-called unskilled workers like the many millions of Americans who work as Walmart cashiers, fast-food employees, hospital staffers, and drivers for Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash.

“I’ve been in meetings where I was appalled by what union leaders said about normal working people,” said McAlevey. “The established unions lost faith that working people could actually organize. Smalls showed them that regular workers could do this work — and they could do it as well as, and for less money than, many professional organizers.”

When Smalls and his fellow TCOEW members officially created the Amazon Labor Union and launched their union drive at JFK8 on April 20, 2021, the first thing he did was turn the S40 bus stop in front of the warehouse into a low-budget, welcome-to-all campaign grounds. To collect the signatures required for a union vote, he planted himself there in snowstorms, rain, and heat advisories, playing guitar, serving meals, ordering Lyfts and Ubers for exhausted employees, and handing out free marijuana. Inside JFK8, the growing crew of ALU members built support elbow to elbow with their co-workers. “If we were gonna form a union at Amazon,” Smalls told me, “I didn’t see how an established union could have done it.”

Such tactics succeeded in uniting the diverse Amazon workforce against its common enemy. One member, Pat Cioffi, an Italian American from Staten Island, was said to have convinced more than 500 workers inside JFK8 to change their votes to “yes” and support the ALU. Most workers liked how scrappy the union was and the fact that the ALU’s “union hall” was a dingy two-bedroom bachelor pad Spence and Daniels had rented in Staten Island. Meetings were held in their living room.

In May 2021, JFK8’s general manager, Felipe Santos, emailed the letter that Washington and Hoeper had written a year earlier accusing Smalls of financial impropriety to every single JFK8 employee in an attempt to delegitimize the ALU, but this effort backfired. No one was going to believe the word of management over Smalls or their co-workers in the ALU, with whom they spent more time than their own families. This was the strength of a worker-led union.

After ignoring Amazon’s assistant general manager’s orders to stop delivering food to workers on Amazon property, Smalls was arrested on February 23, 2022. Some sources suggested to me that Smalls had intentionally tried to provoke the confrontation. If so, it was a brilliant move: The arrest, and the widely shared video of Smalls in handcuffs being shoved around by police, reinforced the notion that Bezos and the company were racist bullies.

Less than six weeks later, on April 1, 2022, nearly 55 percent of JFK8 employees who voted said they wanted ALU to represent them. Smalls celebrated by popping a bottle of Champagne and announcing to millions of viewers on the internet and cable news, “We went for the jugular, and we went for the top dog, because we want every other industry, every other business, to know things have changed.”

After the vote, ALU members campaigned to unionize the LDJ5 facility, which sits just across the street from JFK8 and is home to 1,600 workers who sort packages for delivery. But now, Smalls was seldom seen. Following his arrest in February, a judge gave him a deferred sentence, and if he were caught trespassing again, he could go to jail. Smalls was also busy. In May alone, he appeared at an event for a fashion-models union, on the late-night show Desus & Mero, and on the “Breakfast Club” radio show with Charlamagne Tha God. He visited a school in Staten Island, gave a speech for CUNY law students, partied at various bars, and posed for photos with Questlove and Zendaya at a Time-magazine gala.

Smalls was suddenly hard for ALU members to reach. It has been widely reported that nearly 100 Amazon employees from across the country contacted him after the JFK8 victory seeking advice on how to unionize their own facilities, but according to one source who had access to the ALU inbox, few of those emails were answered.

When one new organizer in the LDJ5 facility told Smalls that she needed help and that his absence from Staten Island was hurting her organizing efforts, he allegedly told her not to be “codependent.” In a meeting, he berated the same organizer so much that she cried, according to someone who was present. He also said that “salts” — those who get jobs at Amazon only to unionize it and who make up one-third of the ALU’s organizers — weren’t real Amazon workers, even while he publicly praised them.

“The fact is we was all burnt out. Not just me but everybody,” Smalls told me later. “Everybody was stressed out at that time.”

Under stress, Smalls reverted to an us-versus-them mentality, once going so far as to tell me that he trusted only the Four Horsemen and Anthony. “It’s crazy how privileged people think they are,” he said. “They jump onto these campaigns; they get involved at the very tail end and act like they’ve been doing this for the last two or three years like I have. Get the fuck out of here — none of them have. Where was you when we started the union? Nowhere to be found. I know who was with me. Everybody else are secondary-role players. Everybody else I can give a damn about.”

Two weeks after the victory at JFK8, Smalls and I drove out to Staten Island, where some of these tensions were already bubbling to the surface. His Suburban was cluttered with posters, a megaphone, a folding lawn chair, Bob Marley–brand rolling papers, and empty boxes; he had signed a lease on a new apartment but was living in a hotel in Elizabeth, New Jersey, until move-in day. At the S40 stop, dozens of employees in hooded sweatshirts and orange work vests poured off the bus. Taped to the bus stop was a flyer urging workers to vote “yes” to support the ALU, on which someone had scribbled “Fuck ALU.”

“We gotta be quick — in and out,” Smalls said. “When I pop up here, security is like, ‘It’s Chris Smalls time!’ ” Despite a growing fear that they would lose the election at LDJ5, there was a festive air at the warehouse, and workers competed with one another to get a fist bump from Smalls as he exited his car. But already, other ALU members believed his notoriety had become a liability.

“People are starting to see him more as a celebrity in my building and not like someone local anymore,” said Mike Aguilar, a worker at LDJ5 and an ALU member. “They ran up to him and were like, ‘Can I take photos?’ And I was just like, What’s going on? People think he’s so famous, he has all that money; people are probably going to believe the rumors a little more. It’s a distraction.”

Those rumors suggested that Smalls had embezzled money to buy himself a Lamborghini and that he had used union funds to buy another ALU organizer a car. Smalls insists none of it is true. He told me he still largely lives off the GoFundMe, and in June he sold a memoir to Pantheon. “I’m broke as hell,” he told me. When I asked if any of the $400,000 the group had received in donations since April had been used for personal expenses, he said, “No. I have a treasurer, and that money goes toward the union. I don’t even touch the money. I have no access to that money. If I need something, I have to request it.” He said one of the reasons he was sometimes hard to reach was because he had to do speaking gigs to pay his rent and child support. “Just ’cause you’re on TV doesn’t mean shit,” he said. “The glitz and glamour doesn’t make you survive.” In the future, the ALU hopes to make Smalls its first full-time salaried organizer, but for now, that’s just one of the union’s many dreams.

The alleged lack of transparency, though, has continued to brew distrust. Dana Miller, a former ALU member from Queens, became alarmed that the organization had no official bank account in July 2021. Smalls, Spence, and Palmer refused, in her opinion, to delegate any tasks that would have allowed others to have access to financial information. (Spence said there is now a formal process to set the budget and allow workers to vote on it.) One day in October 2021, after Miller suggested the ALU get an accountant, the tension exploded at the S40 bus stop. Smalls demanded that Palmer, as Miller recalled it, “cut her off all the channels,” and soon she was removed from the union’s Slack and Telegram, the equivalent of being kicked out of the organization. “It was a total dictator move,” she said.

Something similar allegedly happened to former member Mat Cusick. Cusick said he had overheard Smalls asking Spence, who was then the ALU’s vice-president, for $800 in cash, which was given without any sort of receipt. When Cusick started to raise questions, he said, he was ultimately pushed out of the ALU last month. Cusick said no one besides Smalls knew why some key decisions were made. “In a democratic union, it shouldn’t be that way,” said Cusick, “and you can’t just blame that on being busy.”

Meanwhile, Amazon had intensified its countercampaign. The company had hired anti-union consultants who circulated inside and outside the facility to dissuade workers from joining. It had begun its own free-food program, handing out coffee and Krispy Kreme doughnuts. Some employees were found destroying ALU literature. Most controversially, Amazon required employees to attend “captive-audience meetings,” sometimes holding more than 20 per day, at which anti-union consultants talked about why joining a union would supposedly lower their wages and “stifle their freedom.” (In April, National Labor Relations Board prosecutor Jennifer Abruzzo issued a memo determining that Amazon’s captive-audience meetings were illegal.)

These tensions shadowed Smalls that day we visited Staten Island. As he and I arrived at the designated meeting spot for an interview he had scheduled with CBS Morning News just beyond Amazon’s property, he received a flurry of texts that prompted him to pull the Suburban to the side of the road. “What the fuck?” he said, reading the messages. He told me he had a stalker of sorts, allegedly a former Amazon employee who posts rumors and allegations on social media. As Smalls read the messages, his phone rang, he answered it, and before I knew what was happening, he had stepped out of the car and was shouting into the phone, “Stop being a dick rider, bro! You don’t got shit going on! Stop texting me. Stop calling me. Get a life! Stop being a leech! You don’t have proof of nothing, motherfucker!”

About 50 feet away stood an astonished CBS News crew.

“You’re famous, aren’t you?” David Pogue, the show’s host, said, walking up and shaking Smalls’s hand.

“Sort of,” Smalls said, jamming his phone into his pants pocket. He explained to Pogue the situation with the stalker and tried to brush it off as nothing remarkable, but the call had clearly frayed his nerves. He tightened his Air Jordan 45s, adjusted his black-and-white bandanna, and removed his jacket so his white ALU T-shirt underneath was more visible as Pogue tucked a mic into it. Smalls kept his Versace sunglasses on, and before the interview began, one of the cameramen asked Smalls if he would like to take them off.

“I’m not actually wearing them to look fly,” Smalls said, clearly annoyed. He explained that he wore the sunglasses because his allergies were acting up and he didn’t want his eyes to look red and puffy. “I’ll be crying on-camera,” he said. And then, after a moment, he added, “But you guys would probably love that, wouldn’t you?”

The infighting in the ALU culminated in the disastrous vote to unionize LDJ5. On May 2, under a low gray ceiling of rain clouds, the ALU’s core members gathered in the plaza outside the office of the NLRB in Downtown Brooklyn to monitor the vote that was being conducted on the ninth floor. When word came down that the ALU had lost, the assembled press had one question: “Where is Chris Smalls?” The face of the new-school labor movement might as well have been on a milk carton — no one knew where he was. Anthony, left in the plaza to represent the ALU, blinked at the strobe of camera flashes.

Finally, nearly four hours after the vote count began, Smalls appeared on the edge of the crowd in a patterned robe and sweatpants, like a weary boxer entering the ring. “Chris Smalls is in the house!” Anthony shouted with delight.

It turned out that Smalls had been in Detroit accepting the annual Great Expectations Award at an NAACP conference, and his flight back to New York was delayed. But his absence raised the obvious question of whether he could balance the hopes of a public that wants a working-class hero with the demands of Amazon workers who need a leader who can make their lives better. What had initially made Smalls so effective in his battle against Amazon was the way in which his life story connected him to workers — but now, as his celebrity grew, that same life story risked alienating him from his base.

“I’m not Superman,” he told the crowd.

Today, Amazon has shifted its main offensive against the ALU to the courtroom. The company said it has 80 witnesses to support its claim that the ALU had engaged in illegal tactics to win, including offering marijuana in a direct quid pro quo for votes, according to a person familiar with the case. The consequences of the case could be enormous for the hundreds of thousands of Amazon workers across the country who aren’t unionized as well as the 8,000 who are. The case is also the first referendum on Smalls’s leadership approach. Were his roguish give-no-fucks methods a brilliant boon or liabilities bound to backfire?

“The stakes of this case couldn’t possibly be higher,” said Jessica Ramos, a New York state senator who has worked with Smalls to limit Amazon’s use of algorithm-based quotas. “Amazon is our Alamo. For our generation, we either organize Amazon or the future of our workforce is doomed.”

Even if the victory survives Amazon’s legal challenge of the vote, Smalls has an almost unfathomably difficult battle ahead back in Staten Island. The April win at JFK8 requires Amazon only to bargain in good faith with the union over a contract. The average time it takes for a newly formed union to reach a contract agreement with an employer in the U.S. is 409 days, according to an analysis by Bloomberg Law, and in about 5 percent of cases, it takes a full three years.* The effort to actually get Amazon to ever agree on raises, greater job security, a reduction in algorithm-based performance quotas, a $30 starting wage, a free shuttle, or any of the union’s other demands could drag on or even fail. The ALU’s members largely aren’t paying dues yet, which means the organization is financially dependent on donations to defray legal costs. “If you don’t get a contract,” said Gene Bruskin, a labor strategist and ALU adviser, “you’ll end up being dissed by everybody. And other workers will say, ‘They won, but what the fuck good did it do?’ ”

In the past few months, the company has fired seven managers at JFK8 who it believed were sympathetic to the union, along with numerous pickers and process assistants, including Cioffi, who was revered as a master organizer. The company has also planned to ban the words union, plantation, and negotiate from a messaging app it is developing for workers. Nationwide, dozens of fired workers have filed complaints with the NLRB stating that Amazon had retaliated against them for trying to form unions, which is illegal, though the company has encountered no serious legal repercussions so far except settling several cases out of court.

One of Smalls’s ongoing sources of anger is that even while Democrats like President Biden expect the electoral support of unions and working people, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have failed to successfully challenge 80 years of policy that have helped strip unions of power. One hardly needs to look further than the revolving door between the Democratic Party Establishment and Amazon’s corporate leadership to see the ongoing effects of the cozy relationship between Democrats and big business: Jay Carney, Barack Obama’s former press secretary, has worked as a top executive at Amazon since 2015, and Global Strategy Group, a Democratic polling firm that supported Biden’s candidacy, had been paid by Amazon to “counter-message” against the ALU in Staten Island.

Biden has promised to be the most “pro-union president ever,” yet so far such claims are largely rhetorical. Amazon recently received a $10 billion government contract, even though it has been charged with hundreds of labor violations.

In May, Smalls met with Biden, Vice-President Kamala Harris, and Marty Walsh, Biden’s Labor secretary, at the White House. Smalls was in Washington to testify in support of the PRO Act, a national bill championed by Senator Bernie Sanders that would strengthen federal labor laws. During his meeting with the president, Smalls urged him to sign the PRO Act into law by executive order. “That pen ain’t broken,” he said. “Trump used it all the time.” But Smalls quickly realized he had been brought there for a photo op so Biden could siphon off some of his clout. “You’re trouble, man,” Biden said, shaking Smalls’s hand.

“People really think that the president is really pro-union?” Smalls later told me. “Get the fuck out of here. What are we talking about?”

As White House staff snapped photos and shot video, Harris then said to Smalls, “The whole world is watching what you’re doing at Amazon.”

“Shit, Kamala,” Smalls thought to himself, growing increasingly annoyed, “they watching you, too.”

This, he stressed to me, is the burden of being Chris Smalls. Everyone — politicians, the media, his cheerleaders online, perhaps even some Amazon workers — expects him to fix what decades of weak labor laws, unrestrained corporate power, and growing inequality have created, and they expect him to do so with little political or institutional support. Even the vice-president, as Smalls understood it, was urging him to do what neither political party had been willing or able to do: bring Jeff Bezos to heel.

“We did something historical,” Smalls said, “and now the pressure is on us to fix the laws in this country, to fix the government, to fix Amazon. But we all need to be doing something, and that starts with the government. They don’t seem to understand that.”

Smalls may be distrustful or even cynical sometimes, but it’s no wonder. He, like those who gravitate toward him, has lived his whole life in a country where hard work can fail to earn you a decent existence and where the working class’s supposed allies have done little to change that fact. If there is a sense of Kismet to Smalls’s rise — that unique alchemy of inevitability and circumstance that creates all heroes — it’s due to the conjunction of his own personality with the anger that raged across the country during the pandemic. Only someone with bravery and ego in equally giant doses would ever have attempted what he did, yet his reward has often been people denouncing him as a megalo-maniac for even trying and as a failure for not winning every single battle.

“This is what we do in America,” said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers. “We have heroes, and we have villains. And then someone becomes a villain if they can’t rise to astronomical expectations.”

In recent weeks, Smalls has begun to piece together something of a strategy to win a contract. “Fuck bringing AOC out to Staten Island. Fuck bringing Bernie out. It didn’t do shit for us,” he said of a highly publicized rally with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sanders that preceded the LDJ5 loss. “We need sometimes to get knocked back down on the ground and get back to basics.” According to a confidential ALU document outlining its “War for Recognition,” the plans consist of an “inside game” and an “outside game.” The outside game of garnering support from politicians and the public to serve as pressure on Amazon is mostly Smalls’s responsibility, a role that will once again challenge him to balance the demands of his public persona with his day-to-day duties as a union leader. The inside game involves bolstering support for the ALU within the facility. It will need to enlist dozens of new leaders inside the deeply polarized warehouse to be able to threaten Amazon with a strike, the most powerful tool to force the company to negotiate. “We’re not anywhere near being able to strike,” Smalls said. “We can’t even say the word strike inside JFK8 right now.”

But the symbolic victories already won by Smalls and the ALU are harder to measure, and harder for Amazon to thwart, and there are signs that his example has caught fire in other parts of the country. Workers at Amazon facilities in Campbellsville, Kentucky, and Albany formed ALU chapters in July. Workers at a warehouse in Atlanta walked off the job ahead of Prime Day, disrupting Amazon’s yearly offering of deep discounts to shoppers.

Smalls has admitted he doesn’t “know how” and he doesn’t “know when” the ALU will win a contract at JFK8, but he feels as though, existentially at least, he’s now back where he started and where he’s most comfortable: alone, locked in a battle of us versus them, with the weight of the world on his shoulders. He said the interview requests have subsided since the LDJ5 loss. Union presidents don’t return his calls. And even though he has secured the support of some old-school unions, including $250,000 from the American Federation of Teachers, he’s still skeptical of powerful players who have never supported people like him. “We’re isolated,” he told me. “You think these people care about us? No, they don’t give a fuck about us. We’re back to square one. They expect me to call, beg, get on my knees. Get the fuck out of here. I didn’t need y’all before, and I damn sure don’t need y’all now.”

*This story has been updated to more accurately reflect the time it takes newly formed unions to reach a contract.

[Wes Enzinna is a writer whose essays and reportage have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Harper’s, London Review of Books, and the New York Times Book Review. He has written cover stories for the New York Times Magazine, Harper’s, and Mother Jones. His essay about traveling through Africa with two of the world’s greatest hitchhikers is a “notable” selection in Best American Travel Writing 2019 and his essay about living in a shack in Oakland is a “notable” selection in Best American Essays 2020. He is working on a book about housing for Penguin Press.]