In Wealthy City, a Marxist Mayor Wins Over Voters

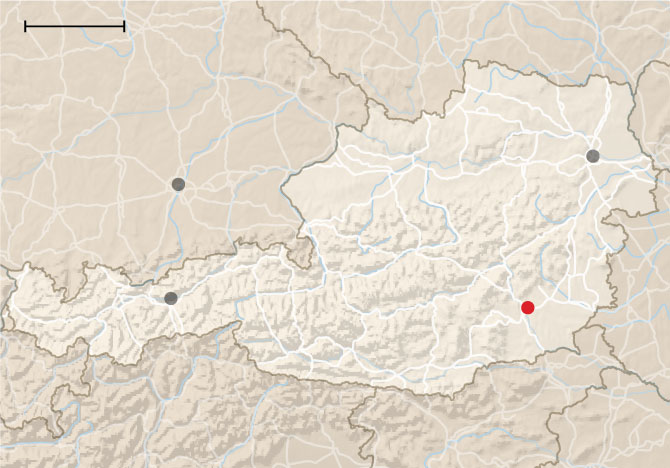

GRAZ, Austria — That the conservative mayor would win yet again, and serve a fifth term, had been treated as a foregone conclusion in Graz, Austria’s second-largest city, a place where it’s not uncommon to encounter local residents proudly dressed in traditional lederhosen and dirndls.

Elke Kahr, the leader of the city’s Communist Party, was equally convinced she would lose again to the slick heir to a trading dynasty who had led the city for 18 years.

So she was as surprised as the journalist who told her the election news last September: The Communists had emerged victorious, and she would be the next mayor.

“He was completely bewildered — and I thought it was a joke,” Ms. Kahr recalled of her election night conversation with the reporter at City Hall.

Newspapers across Europe started calling the city “Leningraz,” a moniker the new mayor smiles about.

“Yes, 100 percent, I’m a convinced Marxist,” Ms. Kahr said in her mayoral office, flanked by the used Ikea shelves with which she displaced the stately furniture of her predecessor, Siegfried Nagl, of the Austrian People’s Party, or Ö.V.P.

Ms. Kahr, 60, is now trying to “redistribute wealth” as much as her role allows her to, she said.

But that doesn’t mean that her Communist Party of Austria, or K.P.Ö., plans to dispossess the bourgeoisie or abolish the free market. Ms. Kahr said her goal was “to alleviate the problems of the people in our city as much as possible.”

To an outsider paying a visit, the city’s problems might not be immediately obvious.

When Arnold Schwarzenegger visits Graz, his hometown, he strolls on clean streets past modern, affordable apartment blocks.

But there are pockets of poverty, and plenty of people are struggling with rising prices and flat wages.

And for nearly two decades, Ms. Kahr, not without controversy, has dipped into her own pocket to help people pay for unexpectedly high electric bills or a new laundry machine. She’ll listen to a problem, ask for a bank account and transfer some money, usually capped at a few hundred euros.

During her political career, she has given away about three-quarters of her post-tax salary. Since becoming a city councilor in 2005, Ms. Kahr’s handouts have amounted to more than one million euros, or approximately $1,020,000.

Political opponents have accused her of vote buying, but “they’re free to do the same,” Ms. Kahr noted. “Besides, it’s not charity,” she added. “I’m simply convinced that politicians make too much.”

As mayor, her salary of about €120,000 after taxes is more than four times the national average, and the €32,000 she keeps for herself suffices. She rides the city’s buses and tramway, shops at budget stores and rents a modest apartment, overflowing with books and records, where she lives with her partner, a retired K.P.Ö. official.

Austria has a long tradition of socialism and has created an expansive welfare system. Health care is universal and universities are free.

But voters have largely shunned the Communist Party ever since Austrians had a front-row seat as the Soviet Union violently crushed a popular uprising in neighboring Hungary in 1956. The K.P.Ö. hasn’t won a national parliamentary seat in any election held since.

Graz, however, has been an anomaly: With the party’s focus on housing, charismatic Communists have sat on the City Council since the 1990s.

None have been as popular as Ms. Kahr.

Supporters and critics alike describe her as approachable, pleasant and a straight shooter. Constituents often compliment her for “not being like a politician,” but more like a social worker.

As mayor, governing in a coalition with social democrats and greens, she now has more influence to steer policies in directions she favors.

So far, that has included capping residential sewage and garbage fees as well as rents in city-owned housing. She has made thousands more residents eligible for heavily reduced annual passes for public transport.

And she’s cut the marketing budget for the entire city, as well as subsidies for all political parties.

Kurt Hohensinner, the new head of the Ö.V.P. in Graz, dismissed these efforts as more symbolic than substantive. Predicting how the city would fare under Ms. Kahr’s leadership, he said, “Graz won’t suffer from communism, but from standstill.”

Notably, Ms. Kahr also canceled several prestige projects, including an Ö.V.P.-led proposal to give Graz’s 300,000 residents their own subway line.

Instead, the city will soon have a new office for social and housing services and more subsidized apartments.

Housing, Ms. Kahr says, is closest to her heart. It’s also the issue that built the Communists’ brand in Graz.

Fearing annihilation at the end of the Cold War, they opened a tenant emergency hotline, giving free legal advice on dubious rental agreements, looming evictions and the failure of landlords to return security deposits.

Poor and wealthy, left and right, called, and word of mouth spread: The Communists care. Often, Ms. Kahr answered the phone.

As mayor, Ms. Kahr tries to be a familiar presence on the city’s streets.

Jumping off the bus at Triestersiedlung, one of the city’s poorer neighborhoods, defined by its 1,200 subsidized apartments, Ms. Kahr complimented the owner on her car, a rare Soviet-made Lada, then headed into the shaded courtyard of a social housing block.

The facades of the apartment buildings were freshly painted, and on this sunny afternoon, its low-income residents were basking on their recently constructed balconies. It’s a luxury most private apartments in Graz lack and one that Ms. Kahr pushed for as a councilor.

As she distributed raised flower beds so residents could grow their own tomatoes and herbs, one of them approached and lauded “Elke” for “still coming to visit us, now that you’re mayor.”

Ms. Kahr reminded the woman that she, too, had grown up there.

i

Given up for adoption at birth, Ms. Kahr spent the first years of her life at a children’s home. Just shy of her 4th birthday, she was adopted. The story goes she cheekily asked a visiting couple for a banana sticking out of their grocery bag; impressed by the little girl’s lack of shyness, the couple adopted her.

Her father, a welder, and her mother, a waitress-turned-homemaker, rented a shack in Triestersiedlung. They fetched water from a well and tended chickens, ducks and rabbits. Their toilet was an outhouse.

Some of her playmates lived in barracks left over from World War II and trudged through the snow in sandals.

“If you grow up in this social environment, you can only pursue a socially just world,” Ms. Kahr said.

Yet she never felt she lacked anything: She remembered devouring the books in the housing project’s library. On Saturdays, when the family visited the public bathhouse, little Elke splurged by maxing out her time in the tub to 30 minutes.

As a young adult she drove to rock concerts across Europe (she likes most music, she said, including socially conscious rap, “though Eminem, not so much”) and tracked down her birth mother, a farm girl. Her biological father was a student from Iran.

The meeting wasn’t to foster a bond, but “to tell her that, no matter the reasons for her decision, for me it was perfect,” Ms. Kahr said.

Rebuked for “speaking like a Communist” growing up, Ms. Kahr was 18 when she decided to find out why.

She looked up the party’s address in the phone book and headed over to the local headquarters.

“She was a godsend,” said Ernest Kaltenegger, her mentor and predecessor as the party’s local head. “Not like other young people who burn bright for a little while — she was serious.”

When the bank branch she was working at closed when she was 24, Mr. Kaltenegger persuaded her to become the second employee of Graz’s K.P.Ö. During a six-month study in Moscow in 1989, she followed the passionate debates there on reform, and believed that “they’d turn the corner.”

Two years later, the Soviet Union dissolved.

Ms. Kahr consoled her older comrades, and focused on her young son, Franz.

In the 1990s, Mr. Kaltenegger campaigned on installing bathrooms in all of Graz’s social housing apartments, and turned the Communists into a local political pillar. He later moved on to the state level on the condition that Ms. Kahr took over the Communist mantle in Graz.

She did, and got off to a stumbling start. Leading the party in the 2008 election, she lost half his voters.

But within five years, she had turned the Communists into the city’s second-strongest party. One likely factor in the party’s win last year was growing discontent in Graz over a construction boom that was snapping up the last plots of undeveloped land. In a K.P.Ö.-organized referendum in 2018, an unusually high voter turnout effectively blocked the rezoning of an agriculture school’s land, a memorable victory for the party.

Often, criticism arises not from Ms. Kahr’s work, but her unabashed embrace of ideology. For example, her admiration for the former Yugoslavia, a multiethnic and nonaligned state run by a dictator, shows a “historical stubbornness,” said Christian Fleck, a sociology professor at the University of Graz.

But constituents don’t seem to care, with her approval rating in June standing at 65 percent.

As mayor, she continues meeting regularly with people who need help, as she did when she was a councilor and logged more than 3,000 visits a year from single mothers, the unemployed or people in precarious housing situations.

Dragging on a cigarette, a vice she can’t surrender, Ms. Kahr reflected on why Communism failed elsewhere.

“It just depends,” she said, “on whether the leaders also live by it.”