You’ve Been Lied to About the 1963 March on Washington

Despite his towering contributions to the Civil Rights Movement, A. Philip Randolph (1889–1979) has somehow faded from popular memory. A black trade unionist and socialist, Randolph’s long political career started in the 1910s (when his Harlem-based magazine the Messenger staked out a pro-labor, pro-socialist position), ran through the 1930s and ’40s (when he gained renown for leading the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the first March on Washington), and stretched well into the ’60s (when he founded the Negro American Labor Council and served as the official head of the 1963 March on Washington).

Randolph’s life alone rebuts the whitewashed versions of the Civil Rights Movement and the 1963 march. Here was a man who saw the struggle against racial oppression and economic exploitation as intimately linked; who located the locus of change in the organized masses rather than the upper crust; who regarded unions as a grand instrument to bludgeon racial injustice.

As historian William P. Jones lays out in the following interview, it was fitting that Randolph headed the August 28, 1963, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. For that march was a union march, a mass working-class march, a march that sought not only to end Jim Crow tyranny and racial segregation but to win a massive federal jobs program, well-funded education and housing, and a living wage for all workers.

Randolph had plenty of pro-labor company at the march: Cleveland Robinson, a key organizer, was head of the New York City local of the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union. Addie Wyatt, a leader of the Packinghouse Workers union in Chicago, organized a large group to come to the march. The Garment and Auto Workers unions footed the bill for the event’s $20,000 sound system. Martin Luther King even originally tried out his “I Have a Dream” rhetoric at a 1961 AFL-CIO convention.

For years leading up to the March on Washington, black labor leaders and rank-and-file workers had used their unions, as Jones puts it, “both as vehicles of economic empowerment of black people and as tools for fighting racism.” When they gathered on that late August day, it was likely the largest-ever march of US union members up to that point. The following spring, with civil rights legislation languishing in Congress, Randolph pulled out another classic labor trick: he threatened to call a general strike. The Civil Rights Act passed that summer.

Jones tells this story to great effect in his 2013 book The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights. He spoke with Jacobin‘s Shawn Gude about the first March on Washington, the central role that black trade unionists played in the Civil Rights Movement, and the unfulfilled promise of the 1963 March on Washington’s radical, mass working-class vision.

SHAWN GUDE

What was A. Philip Randolph trying to accomplish with the first March on Washington?

WILLIAM P. JONES

There were two main demands. One was the integration of the armed forces, and the other was a prohibition on employment discrimination, both for federal contractors and the military.

When they initiate the march, the US is not yet in the war. Franklin D. Roosevelt is saying that we have to be the “arsenal of democracy,” and there’s a huge flood of federal money into contractors. The auto companies are retooling to make weapons and airplanes, the shipbuilding industry is gearing up, etc. But black people are being shut out of these jobs.

A student activist movement gears up in protest against the draft: people are saying, I’m not going to sign up and get drafted into a Jim Crow army. And that gives Randolph the sense that there could be this mass mobilization along the lines of the anti-colonial movement in India. He’s saying, We can bring a hundred thousand people to Washington in the midst of the preparation for the war, and that will force the hand of the government.

It’s really striking, looking back, how threatening that was perceived. Thousands of people demonstrating in Washington is kind of old hat at this point, but it certainly was not back then.

WILLIAM P. JONES

It was a big deal. In ’63, it was seen as a real threat, but especially in ’41, people freaked out. The NAACP’s Roy Wilkins was like, No way, we can’t do that — it’s going to backfire, it’s going to create rioting.

There had been rioting during the war. There was a streetcar protest in Washington, DC, where Southern elected officials had encouraged soldiers to beat up protestors. There was the memory of the Bonus March, which ended in troops being called out and beating everybody up and burning down the Bonus Army village. People pointed to the fascist March on Rome.

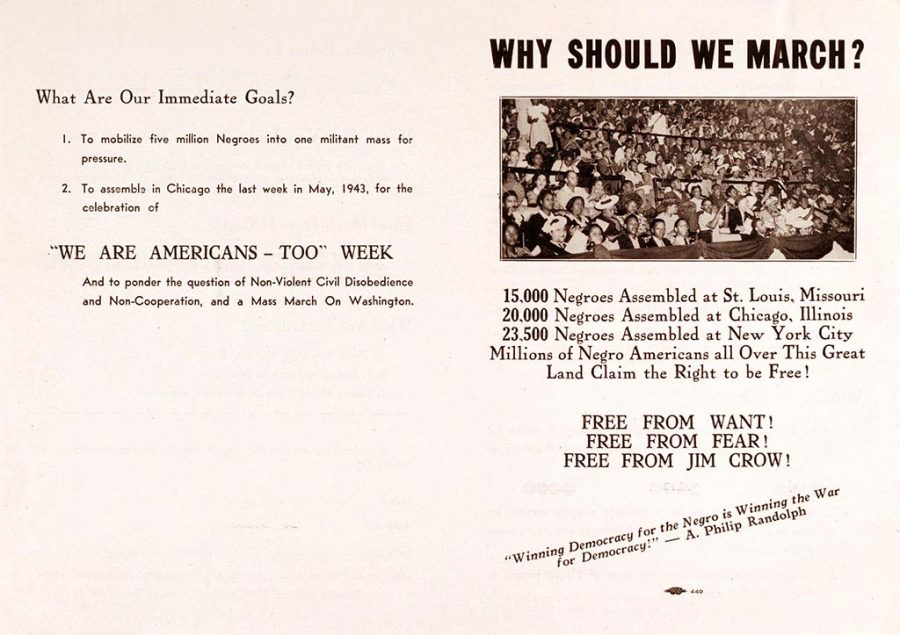

A March on Washington Movement flyer, 1941. (Library of Congress)

So there was a combination of paranoia and hyperbole, and then a real threat of violence.

FDR tried ignoring the movement — he said, If I meet with you, it would show that this mob politics works. He sent Eleanor Roosevelt and New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia to try to talk people out of the march. Then he finally caved and met half their demand: he prohibited employment discrimination by contractors and created the Fair Employment Practices Committee.

This definitely raised Randolph’s stature and gave him something to point to and say, Look, this works. We didn’t even have to march and we got this, so it’s effective.

A lot of people involved in the march were actually pissed that he called it off, because they were ready to go. But it’s not clear how many people would’ve showed up, so I think that was part of his calculation. He recognized that if they showed up with like fifty thousand people, it would still be a lot, but it would be only half of what they had said.

SHAWN GUDE

By this point, there’s an ascendant strain of black politics — exemplified by Randolph — that sees the black working class as the primary driver of change. That’s a real shift from earlier, more elite-driven brands of black politics — Booker T. Washington–style conservatism being the most famous, but even W. E. B. Du Bois’s idea of the “Talented Tenth.” Could you talk about the mass, working-class, black politics embodied by Randolph’s 1941 March on Washington? And how did the March on Washington Movement’s relative success affect people’s sense of mass politics as a possible strategy going forward?

WILLIAM P. JONES

As I said, a lot of people in the leadership of the NAACP and the Urban League remained very committed to the idea that the way to fight for racial equality was through a kind of respectability politics —demonstrating that black people could be just as educated and behave like white people supposedly did.

The NAACP was committed to working through the courts and through access to elected officials, and Roy Wilkins was very suspicious of the idea that you could win anything through demonstrations and the like. Disruptive mass movements, the idea that working people were going to be at the forefront of change — he saw that as naive.

So it’s important to recognize that what Randolph was saying was still controversial. He was a radical. Randolph’s position was that mass politics is the way the vast majority of black people can get involved in the movement. He saw it as a way of building a biracial working-class movement.

The real thrust of this new mass politics was coming from two sources. One was young, college-educated, black radicals, mostly women: Ella Baker, Pauli Murray, Dorothy Height, Bayard Rustin. They’re pointing to the anti-colonial movement in India as a model.

And people are like, Well, India is still a colony and the movement there is getting beat up. It is a majority movement that’s trying to get rid of this tiny British minority — it doesn’t apply to the United States. If you do it here, it is going to get people killed. And that’s what happened: when Bayard Rustin started these bus rides [the original Freedom Rides of the 1940s], he got beat to hell and thrown in jail.

So this mass approach is very controversial. The NAACP and the Urban League are really hesitant to get involved in the March on Washington ’41. They do it at the last minute, only when it’s clear that it’s going to bring a significant group of people to the Capitol.

The other force that’s really important is the black working class — people who are involved in the labor movement during the Second World War, mostly in the CIO. It’s people in the autoworkers’ union, in the needle trades’ unions, in the warehouse and packinghouse workers’ unions. They take leadership in the movement, and they become the base of the NAACP, sort of in spite of the NAACP’s leadership.

SHAWN GUDE

Your book provides a wonderful account of labor’s foundational role in the Civil Rights Movement in these years. I was wondering if you could talk about that rich labor ecosystem — unions like the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and figures like Cleveland Robinson and Addie Wyatt — which we don’t hear about anymore, but was responsible for pushing a black working-class politics.

WILLIAM P. JONES

These are people who came of age in the late ’30s, early ’40s, mostly in CIO unions, and they’re exposed to a wing of the union movement that’s deeply committed to interracial cooperation and anti-racism. They’re not naive about it — they’re often fighting within their unions against white leaders resistant to challenging racism. But they see a strong possibility for using unions both as vehicles of economic empowerment of black people and as tools for fighting racism.

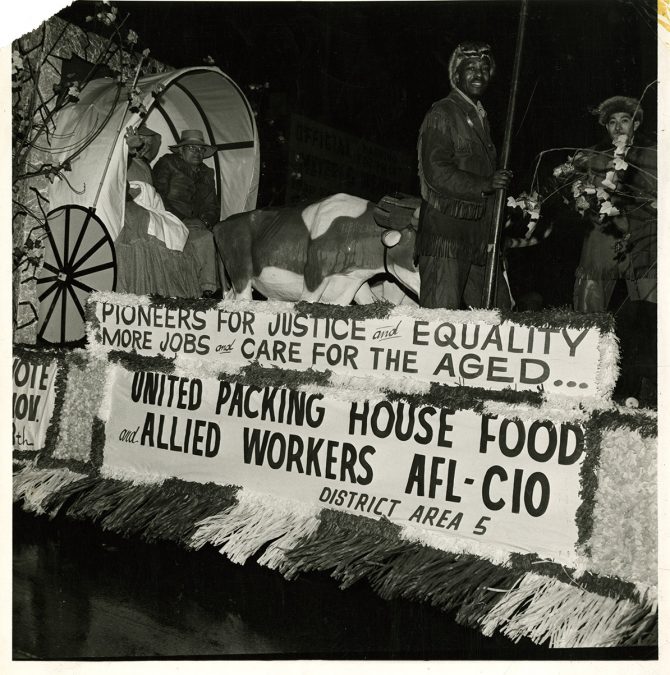

United Packinghouse Workers at a Chicago parade, circa 1960. (Chicago Public Library)

That idea was hard to have faith in before the CIO. But they came up with that [“civil rights unionism“] being a real possibility, and they ran with it. In places like Detroit and Chicago and New York, black people could rise into significant positions of power within the union movement, and that made a huge difference.

They’re also deeply connected to the NAACP — as I said before, in some ways they take over the NAACP. That creates the basis of a mass movement that facilitates the ’41 March, and really, in the ’50s and ’60s, becomes a significant driving force of the Civil Rights Movement.

They’re raising funds in all the big Northern cities and sending them down to Montgomery and New Orleans and Birmingham and other places where local movements are developing. Those movements wouldn’t have taken off without that kind of support.

SHAWN GUDE

Can you talk more about the Sleeping Car Porters? I guess this is becoming a major theme of our conversation, but it’s sort of amazing how forgotten they are given the central role they played in the movement.

WILLIAM P. JONES

Sleeping car porters were based in cities all over the country and were connected because of their work on the trains. They became these sort of communication networks, circulating information along the rails and building community bases of support. Women’s clubs were an important part of this movement — the Sleeping Car Porters had a women’s auxiliary that allied with the National Council of Negro Women and the YWCA.

So there are these community-based organizations that are able to mobilize, and you see that in every single place where there’s an upturn in civil rights mobilization in the ’50s. It’s based in these networks that had been built up since the 1920s.

What’s funny about the sleeping car porters is that, by the ’50s, it’s sort of a dying industry. The auto industry is taking off, and you have the airline industry too. But the union has the funds and, importantly, this national network that is able to mobilize and keep going. In a lot of ways, the growing industrial unions became more important to the movement, but the Sleeping Car Porters created a model that a lot of activists in those industrial unions followed. And it becomes this sort of glue, and even as it’s running into hard times, it’s created this leadership cadre — people like Randolph, like E. D. Nixon, who led the movement in Montgomery.

In almost all of the big cities, there are people who come out of the Sleeping Car Porters that are important civil rights leaders.

SHAWN GUDE

You mentioned the important role that women played in the Sleeping Car Porters, but often women were sort of pushed to the side in the movement, including being excluded from the leadership of the 1963 March on Washington. Can you talk about some of that exclusion?

WILLIAM P. JONES

It’s complex. After the ’41 march was called off, the fight for fair employment did focus a lot on women’s jobs, largely because the civil rights organizations walked away from it, and the ones that kept going were the National Council of Negro Women and the YWCA. They explicitly shift and say, Women are getting jobs during the war. We need to have a campaign to fight to keep those jobs.

So there are a lot of cases in which women are in leadership, it’s just that the top leadership isn’t recognizing them, and often explicitly trying to push them out. The male leadership of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters is really explicit in saying that there are too many women involved.

Ella Baker in 1964. (Wikimedia Commons)

But in spite of that, women are often pushing the movement in directions that it wouldn’t have gone. It’s women — Pauli Murray probably being the most important — who bring the idea of Gandhian nonviolence into practice.

Or look at someone like Ella Baker, who consciously avoided the spotlight and was like, I don’t want to be a leader, I want people to help people lead themselves. That’s actually extremely effective leadership, but it’s one that does not get recognized. So I think that combination of working in the trenches, doing the hard work, and then the blatant sexism, meant that they often didn’t get recognized for the leadership they were doing.

SHAWN GUDE

Let’s talk about the ’63 March on Washington. Obviously, the most remembered part is Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. But that omits a lot about the event. I was wondering if you could talk about the march, which explicitly paired the fight against Jim Crow with the fight for economic justice.

WILLIAM P. JONES

There are a couple things I would emphasize. One is the painstaking attention to the message — how it was articulated and how it would be projected. Bayard Rustin insisted they get this $20,000 sound system because he said that if people in the back can’t hear, they’re not going to be engaged. They had this whole security system within the march to try to dissuade people from getting into arguments and fights — the Nazi Party was there, taunting people, trying to cause trouble. So there was this very meticulous attention to getting the message out and preserving the image of the march.

Just getting people there was a tremendous endeavor. It was a weekday, so people had to take off work. Most people came from big Northern cities, and the unions often would hire trains. For most people, they were on the train or the bus overnight.

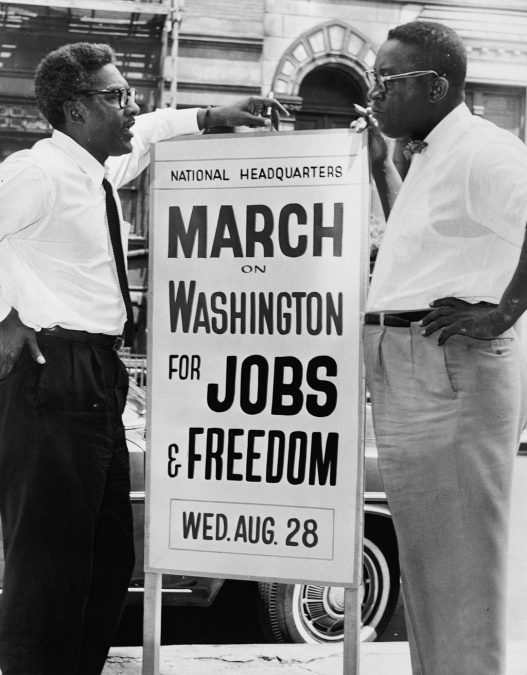

Bayard Rustin and Cleveland Robinson ahead of the 1963 March on Washington. (Wikimedia Commons)

King’s speech came at the end of this really long day. He was purposely trying to get people’s spirits up, trying to rally people before the end. What’s tragic about the way we remember the march — because they went to such extents to make sure everybody knew what the march was about — is that King’s was the least specific speech about the goals of the march.

Flyers were printed up with instructions on attending the march, then, really boldly, the demands of the march. Then they read out the demands at the beginning and at the end, and the speeches were really specific about the connection between economic justice and racial equality.

There was a lot of grumbling after the March that the media didn’t pay attention to the economic demands, but at the moment, it was pretty unavoidable. The full thing was broadcast on radio and on television. Newspapers were there. It’s only over time that the image of the march was narrowed down, and that colorblindness was seen as the main goal of the march, which it was not at all.

SHAWN GUDE

I was kind of astounded to learn in your book that in the spring of 1964, several months after the march, and with the civil rights bill still stuck in Congress, Randolph called for what was effectively a general strike. Could you talk about the aftermath of the march, and how the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was finally passed?

WILLIAM P. JONES

A couple things about the Civil Rights Act are important to remember. John F. Kennedy introduced that bill in the summer of 1963, and he was adamant that it should not have the fair employment provision. He thought that would alienate Northern Republicans who might otherwise support a bill focused on voting rights, integration of schools, etc. An important part of the march was that they wanted to add an Fair Employment Practices Committee provision to the bill. And that’s what the march did.

There’s this idea that the march sort of convinced white people that they had been too hard on black people and, you know, that black people were okay. That’s obviously wrong. But it did convince people like George Meany and Hubert Humphrey — liberals within this coalition — that they had to support this kind of thing, and that they could actually get these fair employment provisions. So the fact that after the march, this coalition came together to pass the bill and keep those provisions in is really important — many people would see what’s now Title VII of the Civil Rights Act as the core of the law, but that was not at all Kennedy’s intention.

In terms of the effects of the march and the next few months, it’s important to remember there was a lot of frustration. It wasn’t clear the law was going to pass. It was being filibustered. And that’s the remarkable moment at which Randolph was like, we need to up the ante. Let’s call for a general strike. And they probably could’ve pulled it off.

The Negro American Labor Council [the organization Randolph founded in 1960] had people in positions of power in all the major industrial unions in all the major cities and in the public-sector unions as well. They could have shut down a few big cities.

The filibuster ended pretty quickly after he called that. I don’t know if that was people recognizing it was a realistic threat or other things, but it certainly showed both the importance of the employment provisions and the power that organized black workers had within the movement.

SHAWN GUDE

What is the March on Washington’s legacy, and what does it tell us about current fights against economic exploitation and racial injustice?

WILLIAM P. JONES

If I would point to one thing, it’s the idea that racial equality is impossible without economic justice. That motivated Randolph for his entire career, and it was the central message of the march: desegregation. Equal treatment based upon race is important, is fundamental, but it’s not going to be substantive without guaranteed access to decent jobs and union protections. These things are integral to the fight for racial equality.

The thing I find particularly frustrating about the memory of the march is that it is seen as this moderate, watered-down, defanged movement — when I think it’s actually the moment at which that political message was delivered most effectively by working people. Philip Foner pointed out that it was probably the biggest march of union members in American history up to that point.

It was a union march. And it was a march of working people demanding economic justice and saying that it is integral to the struggle for racial equality.

SHAWN GUDE

You have a great part in the epilogue where you write, “Ironically, frustration with the failure to realize the more radical goals of the March on Washington led some to suggest that its agenda had never been so ambitious.”

WILLIAM P. JONES

Yeah, there’s an incredible position that emerges, I think, in the ’80s and ’90s that the march was successful because it was moderate. That’s just insane. There’s absolutely no truth to that. It’s actually the reverse. It was successful because it was expansive in its demands, and because it was radical and militant. That’s a really important lesson that often gets overlooked or lost.

I also think we should make clear the present connection between the struggle for racial equality and for economic justice — between the sort of new union movement and the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s important to see them as intimately aligned, and that’s an important legacy of the march.

We’ve seen this during the pandemic and the racial inequalities in the workforce. The people who were most likely to be seen as essential workers are underpaid, disempowered, and tend to be people of color. Race and class are deeply intertwined.

And we saw this union movement emerge from frontline workers at places like Amazon who were deeply affected and who were largely people of color. I think people should be conscious of the fact that that’s a constant in American history, and that it has deeply shaped the union movement and the Left.

William P. Jones is a professor of history at University of Minnesota. He is the author of The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights and The Tribe of Black Ulysses: African American Lumber Workers in the Jim Crow South.

Shawn Gude is a senior editor at Jacobin. He is currently writing a biography of Eugene Debs.

The new issue of Jacobin is out now. Buy a copy, or a special discounted subscription today

If you like this article, please subscribe or donate to Jacobin.