Green Tide Rising in Latin America

Latin Americans looked on in shock as the Trump-loaded U.S. Supreme Court in June stripped women of a basic right that they had taken for granted for decades. Since 1973, women in the United States could choose to terminate a pregnancy, while in Latin American countries, women suffered clandestine abortions and imprisonment for deciding if and when to enter motherhood. Now powerful women’s movements in Mexico, Argentina and Colombia have won access to the right to choose, just as women in half the U.S. states are on the verge of losing it.

Mexico’s Supreme Court unanimously declared it unconstitutional to penalize abortion on Sept. 7, 2021. The decision, centered on a woman’s autonomy, affirmed that criminalization violates the sexual, reproductive and human rights of women and discriminates against “women and persons with the capacity to become pregnant.” Tens of thousands of Mexican women poured into the streets to celebrate the decision.

“It is really fundamental in concrete terms that in this country no woman can be imprisoned unjustly for exercising her right to choose,” Karla Micheel Salas, a Mexican feminist lawyer-activist, told me.

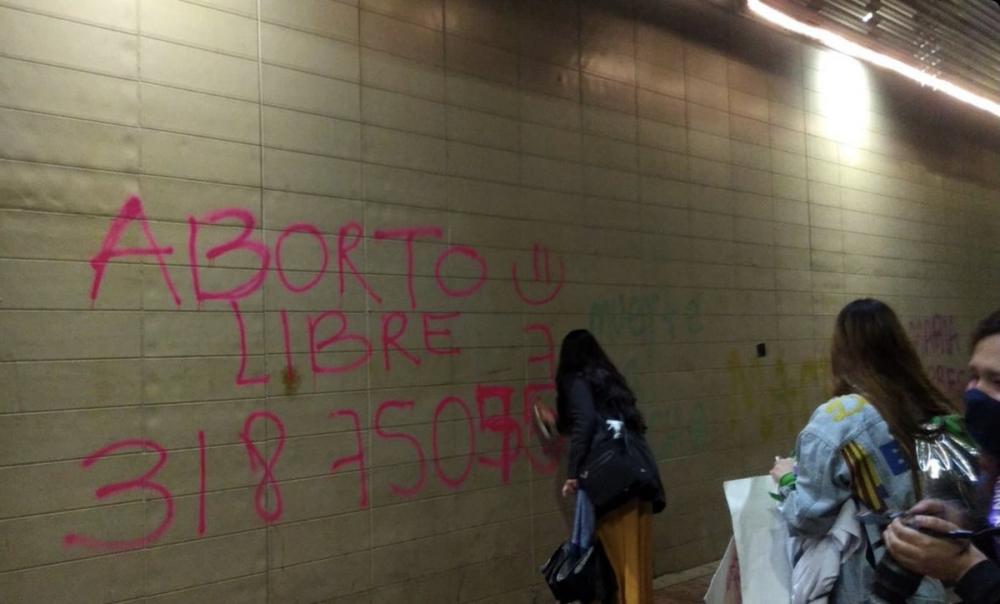

The green tide

Mexico’s victory was the result of decades of feminist grass-roots organizing and strategic litigation. It also received a gust of wind in its sails from the Argentine women’s victory in December 2020, when congress passed a law allowing abortion during the first 14 weeks of pregnancy. What became known as “the green tide” — after the green bandanas worn by women in Argentina to symbolize life — fueled movements throughout the hemisphere.

The green tide and previous movements broke down social taboos against talking about abortion and mobilized people to defend their rights. The change at the community level happened silently, as a reality that had been kept hidden by associations of sin and personal shame was placed in the public sphere.

Women in Mexico first had to build a movement that worked on three main fronts: pressuring the state to guarantee the right to abortion as the domain of a woman’s choice; educating and galvanizing public opinion in favor of women’s rights; and creating networks to accompany women who decided to abort, when it had to be done clandestinely and under threat of prosecution. These strategies were carried out simultaneously, and all faced opposition from the right wing and from the state that put the women involved at great risk.

The bravery and perseverance of women activists enabled the green tide to advance. Colombia legalized abortion in February 2022, freeing more millions of women and their families to make independent reproductive decisions.

The next showdown could be in Honduras, which has among the most draconian anti-abortion laws in the region, rammed through by the government of former president Juan Orlando Hernandez, now indicted for drug trafficking in the U.S. The new progressive president, Xiomara Castro, has promised feminist allies to support efforts to eliminate the constitutional ban on abortions to at least allow it in cases where there is a risk to the pregnant woman or girl’s life or health, the fetus is not viable, or the pregnancy is a result of sexual violence. Chile is also in line, as the right to abortion is included in the proposed constitution that will go before voters on Sept. 4.

Backlash

But the U.S. Supreme Court decision has once again proven that progress in women’s freedom and rights are always vulnerable to reverses. Latin American countries face a powerful Catholic Church hierarchy and Christian fundamentalist movements that invest enormous resources in restricting women’s rights. Governments maintained the prohibition on abortion even as majority public opinion and international human-rights standards evolved. Several countries, notably Nicaragua, El Salvador and the Dominican Republic, have complete bans on abortions in all circumstances. Recent health research estimates that as many as a quarter of pregnancies result in miscarriage in the first trimester, which means that miscarriages too are subject to criminal investigations and punishment.

The lessons from Latin America are that grassroots mobilization works to change laws that deny women’s rights, but also that women cannot depend entirely on the patriarchal state to guarantee their rights.

The legacy of Catholic colonialism and the reality of neocolonialism form major barriers in the fight for women’s reproductive rights. Control over women’s bodies and reproduction was key to the colonial conquests and now to imperialist efforts to exploit scarce natural resources through extractive industries such as mining, oil and gas exploitation, monocropping and hydroelectric plants. As women lead the efforts against these projects being imposed on their lands, unwanted pregnancies and criminalization of their sexuality force them to retreat from the public sphere and severely affect their mental health. Powerful economic interests benefit from women’s confinement to domestic labors, and many of those interests emanate from the United States.

Christian fundamentalism has played a role in the rise of reactionary movements in both the United States and Latin America. In recent Latin American elections, far-right candidates with explicitly anti-woman platforms supported by religious fundamentalists have gained power as their numbers rise. Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, elected in 2018 in large part because of the support of fundamentalist groups, tweeted after the Argentine legalization, “If it depends on me and my administration, abortion will never be approved on our soil.”

Experts warn that the Supreme Court ruling could fuel a backlash in Latin America and the rest of the world. Right-wing anti-abortion organizations are tightly linked and internationally funded. Many have set up “crisis pregnancy centers” throughout Latin America that offer disinformation to frightened young women facing an unwanted pregnancy. They lobby against all efforts to respect women’s rights over their own bodies. Abortion-rights organizations warn that the ruling could increase funding to these groups, and have documented that most opposition to abortion rights in Latin American countries is driven by organizations from outside the country. This encouragement of fundamentalists will also increase harassment and persecution of abortion seekers and providers.

The Supreme Court ruling is also likely to interfere with U.S. organizations abroad working for sexual and reproductive rights. The 1973 Helms Amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act has long prohibited federal funds being used for abortions abroad. The “Mexico City Policy,” initiated by President Ronald Reagan in 1984, banned U.S. foreign aid from going to any non-governmental organization that provides abortion-related services. The policy was rescinded by Bill Clinton, reinstated by George W. Bush, rescinded by Barack Obama, reinstated and strengthened by Donald Trump, and rescinded again by Joseph Biden. This Democrat-Republican ping-pong game has wreaked havoc with women’s health services abroad and points to the need for structural guarantees for women’s basic rights.

A new era of feminist solidarity

As a new phase of struggle begins in the United States, a new phase of solidarity has also begun. Feminist organizations in Mexico are working intensely with organizations in the United States to create networks to accompany women having medication abortions, using knowledge and experience they developed during decades of prohibition. The World Health Organization has long recommended medication abortion as a safe and effective method of terminating pregnancy.

“Because abortion had been restricted for so many years in Mexico, there came a moment when we in the movement had to go the other way — not betting exclusively on legislation, not just relying on the courts or that access to health services be guaranteed,” explains Verónica Cruz, a pioneer in the formation of these networks in Guanajuato, one of the most conservative states in the country. “In addition to that, we began to work on the social decriminalization of abortion, woman by woman, guaranteeing every woman who needs it her right to abortion with social accompaniment. That has made a difference in Mexico and throughout Latin America, and I believe that today the United States has the opportunity to learn from this experience, to learn from the South again.”

Control over women’s bodies and reproduction was key to the colonial conquests and now to imperialist efforts to exploit scarce natural resources.

The lessons from Mexico and Latin America are that grassroots mobilization works to change laws that deny women’s rights, but also that women cannot depend entirely on the patriarchal state to guarantee their rights — even though that is supposed to be the state’s job. Autonomous women’s organizations in Mexico made huge strides under cover in access to abortion, contributing to countless women’s mental and physical health, and also preparing the ground for legalization.

This is not to say that legalization is not necessary. All women need the right to have medical backup and to talk to professionals about their decision to terminate a pregnancy. Most of all, they need the assurance that they will not be prosecuted. However, in Latin America, we have learned how to organize and how to access this right with and without the blessings of the state. The issue here is not whether to “permit” a medical procedure, it is how far the state should be allowed to intervene in women’s personal lives. Mexico’s decision is perhaps the clearest yet to legally and constitutionally locate the decision in the realm of women’s life choices, with no legal grounds for the state to dictate one way or the other.

This is a dangerous moment for women’s rights in the Americas. But women’s movements have perhaps never been stronger in Latin America. In Chile, feminists mobilized nearly 2 million people on International Women’s Day in 2020 and have achieved the inclusion of women’s rights, including the right to abortion, in the proposed constitution. Mexico’s “8M” demonstrations on the same day gathered hundreds of thousands of marchers around the country. In many countries, feminist and women’s movements are the strongest autonomous grass-roots movements, challenging right-wing and supposedly progressive governments alike.

Even a chill factor from the United States will not turn back the green tide. Now the challenge is to make it global, to recognize how much strengthening or weakening restrictions on the rights of women in one country can affect their rights in another. If we can leverage the lessons learned, the organizing methods and the analysis of the threats we face, we can move forward together and have women in nations throughout the world, including the United States, filling the streets with green bandanas and the assurance that their daughters and granddaughters will experience the joy of sexual freedom and the satisfaction of choosing their own life courses.

[Laura Carlsen is coordinator of Global Learning and Solidarity with Just Associates (JASS). A dual Mexican-U.S. citizen, she lives in Mexico City and writes on U.S.-Latin America relations.]

Please support independent media today! Now celebrating its 22nd year publishing, The Indypendent is still standing but it’s not easy. Make a recurring or one-time donation today or subscribe to our monthly print edition and get every copy sent straight to your home.