60 Years of No Progress on Black-White Unemployment Equity

60 Years of No Progress on Black-White Unemployment Equity

By Algernon Austin

Center for Economic and Policy Research

February 1, 2023

https://cepr.net/60-years-of-no-progress-on-black-white-unemployment-eq…

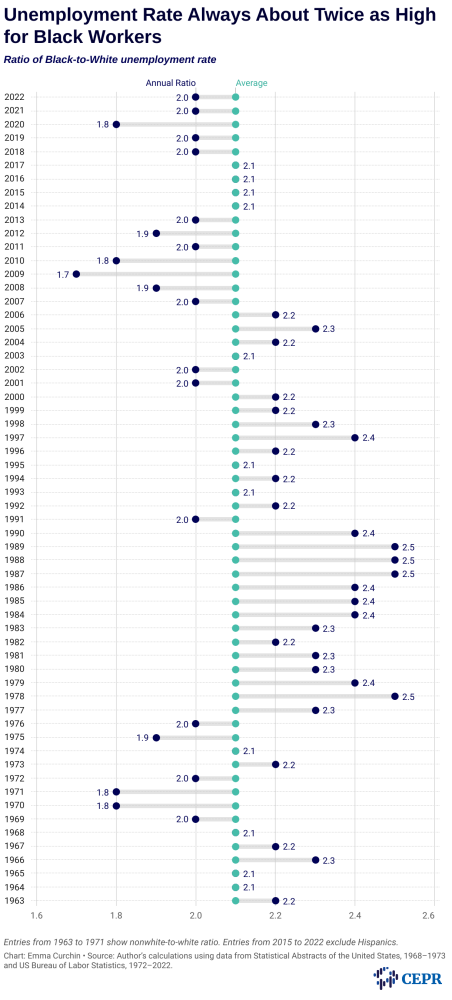

Regardless of whether economic conditions are good or bad, Black jobseekers are less likely to find work. From 1963 to 2022, the Black unemployment rate has been roughly twice the White unemployment rate. There have been times when the Black-to-White unemployment-rate ratio was somewhat higher and times when it was somewhat lower, but the average of the ratios over this period is 2.1. This means that, if one looks at the unemployment-rate ratio alone, there has been no progress in providing equal employment opportunity for African Americans over the last 59 years. The last Congress did nothing to directly address this disparity, so there is no reason to expect it to narrow this year.

Anti-Black discrimination in hiring plays a major role in this permanent inequality. The strongest evidence for discrimination can be found in field experiments where researchers have Black and White “testers” apply for jobs presenting similar qualifications or where they send out similar resumes with stereotypically “Black” and “White” names. A meta-analysis of 28 of these experiments over a 25-year period found consistent discrimination against Black applicants. There need to be stronger anti-discrimination policies and enforcement if the United States hopes to have equal opportunity in employment for all.

Another helpful policy would be a targeted federal program for subsidized employment. Joblessness can be concentrated in segregated and disadvantaged Black communities. For example, in the third quarter of last year the White unemployment rate in the District of Columbia was only 1.5 percent. The Black unemployment rate, however, was 10.1 percent. One way to move toward employment equity in the District of Columbia would be to target a subsidized employment program to the Black section of the city. If policymakers create a national subsidized employment program targeted to disadvantaged communities, it can help achieve full employment for all regardless of race, gender, or region.

*********

When the WPA Created Over 400,000 Jobs for Black Workers

By Algernon Austin

Center for Economic and Policy Research

February 9, 2023

https://cepr.net/when-the-wpa-created-over-400000-jobs-for-black-worker…

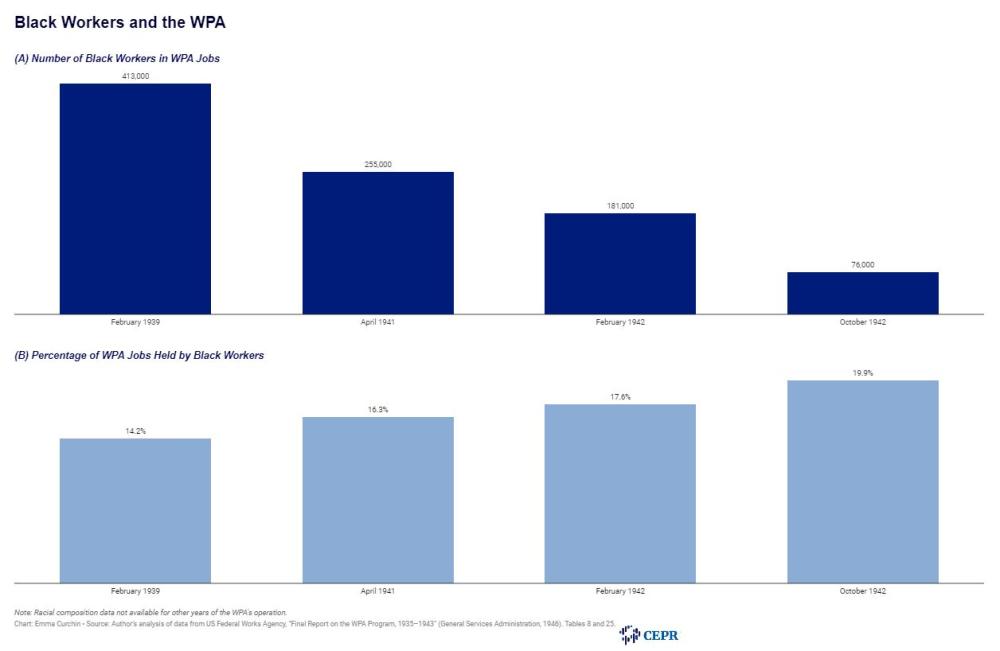

In response to the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) created jobs for over 8 million people between 1935 and 1943. While data on the racial composition of WPA workers isn’t available for all of these years, the data we have for 1939, 1941, and 1942 make clear that the WPA employed hundreds of thousands of Black workers. At its peak in 1939, the WPA employed over 400,000 Black men and women (Figure A) who accounted for one of every seven WPA workers (Figure B). These approximately 400,000 jobs would be equivalent to roughly 1.4 million jobs in today’s larger labor force.

The WPA shows that the federal government can provide subsidized employment for a large number of individuals doing all types of work. The WPA was involved in a wide variety of construction projects, including building roads, airports, housing, sewers, and parks. Although most of the work was in construction, the WPA also supported manufacturing, service work, recreation, and the arts. Not only did Black workers participate in the wide range of work supported by the WPA, a portion of WPA funds was spent on building or repairing segregated Black schools, colleges, hospitals, and public housing. The WPA also funded Black scholars doing research on Black history, and the work of Black artists.

The United States during the 1930s and 1940s was a country with strong and overt anti-Black racial discrimination. The WPA provided jobs for hundreds of thousands of Black people but within a system of racial hierarchy. Despite some new federal requirements requiring equal treatment, Black workers were often placed at the back of the line for jobs, and they were often relegated to the lowest paid positions regardless of their skills. (See Cheryl Lynn Greenberg’s To Ask for an Equal Chance: African Americans and the Great Depression for more details.)

As the US economy revived with the growth of the defense industries serving World War II, the WPA wound down and then ended in 1943. Just as Black workers were among the last hired for WPA jobs, when the US economy recovered, they were among the last hired into the reviving US economy. This meant that Black workers became relatively more dependent on the WPA as White workers were more able to obtain conventional work. As a result of this dynamic, as the economy recovered the share of Black workers in WPA jobs increased. As Figure B shows, the Black share of WPA jobs was 14.2 percent in 1939, and had increased to 19.9 percent by 1942. The WPA provided jobs that helped many Black families survive the Great Depression, but within a context of strong White employment preferences.

Today, it is important to remember that the federal government can create a large-scale subsidized employment program. Although the country is experiencing a historically low national unemployment rate, there are many communities that are still struggling with high unemployment. There are still roughly 15 million people of all races who are unable to find work, but Black people are overrepresented among the jobless. The country can still benefit from a subsidized employment program targeted to the communities facing high rates of joblessness, but this time without the anti-Black racial discrimination. Sign on to a call for a federal subsidized employment program here.

Algernon Austin is the Director for Race and Economic Justice at the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Algernon Austin has conducted research and writing on issues of race and racial inequality for over 20 years. His primary focus has been on the intersection of race and the economy.

Austin was the first Director of the Economic Policy Institute’s Program on Race, Ethnicity, and the Economy where he focused on the labor market condition of America’s workers of color. He has also done work on racial wealth inequality for the Center for Global Policy Solutions and for the Dēmos think tank. At the Thurgood Marshall Institute, the think tank of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., he worked on issues related to race, the economy, and civil rights.

Austin has a Ph.D. in sociology from Northwestern University, and he taught sociology as a faculty member at Wesleyan University. He has discussed racial inequality on PBS, CNN, NPR, and other national television and radio networks. His most recent book is America Is Not Post-Racial: Xenophobia, Islamophobia, Racism, and the 44thPresident.

The Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) was established in 1999 to promote democratic debate on the most important economic and social issues that affect people’s lives. In order for citizens to effectively exercise their voices in a democracy, they should be informed about the problems and choices that they face. CEPR is committed to presenting issues in an accurate and understandable manner, so that the public is better prepared to choose among the various policy options.

Toward this end, CEPR conducts both professional research and public education. The professional research is oriented towards filling important gaps in the understanding of particular economic and social problems, or the impact of specific policies. The public education portion of CEPR’s mission is to present the findings of professional research, both by CEPR and others, in a manner that allows broad segments of the public to know exactly what is at stake in major policy debates. An informed public should be able to choose policies that lead to improving quality of life, both for people within the United States and around the world.

CEPR was co-founded by economists Dean Baker and Mark Weisbrot. Our Advisory Board includes Nobel Laureate economists Robert Solow and Joseph Stiglitz; Janet Gornick, Professor at the CUNY Graduate School and Director of the Luxembourg Income Study; and Richard Freeman, Professor of Economics at Harvard University.