New Cars Have Become Luxury Items

At some point in the not-too-distant past, a new car became a luxury purchase.

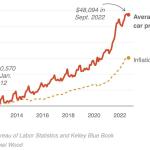

The average price for a new vehicle hit $49,500 at the end of last year, compared to $38,948 just three years earlier. Skyrocketing interest rates pushed the average monthly car payment on a five-year loan to $723 in March.

New vehicles priced under $25,000, a range that the average American might deem affordable, now account for less than 5 percent of all sales.

Customers who walk onto a dealer’s lot expecting such enticements as zero-APR financing and thousand-dollar rebates are in for a surprise: For the first time in recent memory, the automobile industry is a seller’s market.

“It is no longer a $25,000, $30,000 transaction. It is a $50,000, $60,000 transaction,” said Patrick Roosenberg, director of automotive finance intelligence at J.D. Power, a data and analytics company that researches the automotive sector. “It is a greater financial commitment than it has ever been.”

The car-and-truck marketplace went haywire during the COVID-19 pandemic, along with much of the American economy. A global shortage in semiconductors, the chips that control everything from airbags to windshield wipers, seeded massive production delays. Toss in pandemic shutdowns and other supply-chain kinks, and the conveyor belt of new cars slowed to a crawl.

At that point, simple economics kicked in. Demand overwhelmed supply. The customer-friendly, let’s-make-a-deal milieu of the typical new-car dealership vanished as quickly as that new-car smell. It hasn’t returned.

Generations of automotive customers have come to expect deep discounts, four-figure rebates and zero-interest financing. In a new-car negotiation, the sticker price was a mere starting point. No longer.

“Most people don’t expect to pay sticker price. People are paying sticker price,” said Jessica Caldwell, executive director of insights at Edmunds, the automotive information-services company. “Vehicles are coming off the truck, and they’re being sold immediately.”

The semiconductor crisis has eased, the supply chain has loosened, and vehicle production has resumed. But most of the cars and trucks rolling off the assembly lines are luxury items.

Between December 2017 and December 2022, the share of all new auto sales priced above $60,000 more than tripled, from 8 percent to 25 percent, according to research by Cox Automotive.

In the same five years, the share of sales under $25,000, a standard cutoff for economy vehicles, shrank from 13 percent to 4 percent.

“The manufacturers have been steering the market toward more expensive products,” said Charlie Chesbrough, senior economist at Cox. “All those bells and whistles, nav-screens, cruise control, all those fantastic and lifesaving technologies cost money.”

More than 90 vehicle models now fetch $60,000 or more, Cox reports. Meanwhile, in five years, the number of models priced under $25,000 has dwindled from 36 to 10.

U.S. automakers have walked away from economy-priced sedans because of thin profit margins and because consumers don’t seem to want them.

“Ford Focus, Ford Fusion, Chevy Malibu, Chevy Cavalier: There’s a long history of the Detroit three making passenger cars,” Chesbrough said. “But they decided, seven, eight years ago, that the margins just weren’t there for them.”

As a result, actual cars now make up only about one-fifth of the Detroit auto market, an industry dominated by high-priced pickups and SUVs.

A $60,000 vehicle costs more money than the average American earns in a year. Yet, car-buyers bear some blame for inflating new-car prices.

Car prices are rising so steeply, in part, because car buyers are loading up on options: upscale sound systems, sunroofs, leather seats and navigation systems that know your destination before you have chosen it. A “fully loaded” vehicle can cost twice as much as its “base price” counterpart.

Automakers make a lot more profit on luxury cars than on value-priced sedans. They are happy to help car-buyers option up.

“People are not pragmatic when it comes to car-buying,” Caldwell said. “They get very emotional.”

They may get more emotional when the invoice arrives.

Interest rates on new-car loans have soared from 4 or 5 percent to “almost 7 percent” in the past year, Caldwell said. Between high sticker prices and brutal interest rates, more than 15 percent of new-car buyers now shell out more than $1,000 in monthly loan payments. Not on their house: on their car.

“It’s pricing a lot of people out of the market,” Roosenberg said. Some buyers are resorting to loans with ever-longer terms of six, seven or even eight years. Longer loans yield lower monthly payments, but at progressively higher interest rates.

Buyers with low incomes and weak credit are fleeing the new-car market. Some of them wind up on the used-car market, where the pickings are not much better.

Used car prices rose by more than half between mid-2020 and early 2022, the market’s peak. Prices have eased, but the average used car still costs upwards of $26,000.

To find a used vehicle priced at $20,000 or less, a standard benchmark for affordability, a buyer may have to settle for an older, high-mileage vehicle, and those are in short supply.

Not surprisingly, many consumers are holding onto their cars. The average age of U.S. cars will hit 12.3 years in 2023 by one projection — an all-time high. It’s not a bad time to be an auto mechanic.

Industry analysts wonder, though, how long all of those aging vehicles can hold out.

“I do think there’s going to be a reckoning for this country at some point,” Chesbrough said. “We’re just not going to have enough personal transportation available.”

Surprisingly, the drop-off in customers hasn’t hurt automakers, at least not yet.

“We actually sold more than 3 million fewer vehicles in 2022 than in 2019,” Chesbrough said. “But revenue was $15 billion higher, because the prices were so much higher.”

But automakers aren’t necessarily happy with the current state of the new-car marketplace. They would rather have more inventory, analysts say, enough cars to restore the delicate equilibrium of supply and demand. The seller’s market has not gone over particularly well with buyers.

“I think consumers have been mad,” said Caldwell, of Edmunds. “Even customers who have a lot of money are looking at interest rates and saying, ‘Why would I do this?’”

If you plan to buy a new car, despite all of the aforementioned perils, then here are some tips from a pro.

“I think consumers need to be their own advocate,” Roosenberg said. “They need to do research. They need to set themselves a budget. And they need to make an informed decision, and not an emotional decision.

“You’re talking about six-, seven-year loans in excess of $700 in payments. What makes sense to me financially? What can I handle? And it’s hard to do, because there are some great vehicles out there, with a lot of extras.”

And here is some counsel from Benjamin Preston, autos reporter at Consumer Reports: “If you’re looking for a car, it has never been more important to research alternatives and cast a wider net to maybe find something outside your immediate locale.”

In the current climate, Preston said, “it’s a good idea to pick a car that you won’t mind hanging onto for a while.”