King David and Boss Daley

Gangs exist where poverty exists and that’s been true in Chicago for more than a 100 years,” tweeted Lakeidra Chavis, a Chicago-based reporter for the Marshall Project, in January 2022. Chavis was writing to criticize current Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s proposal for a new law that would allow the City to sue gangs and seize the assets of anyone the Chicago Police Department (CPD) alleges is in a gang, because the law would directly worsen Chicago’s obscene levels of poverty and precarity that produce the violence in the city. However, Chavis also made the important point that Chicago gang history stretches much farther back than many Chicagoans may realize.

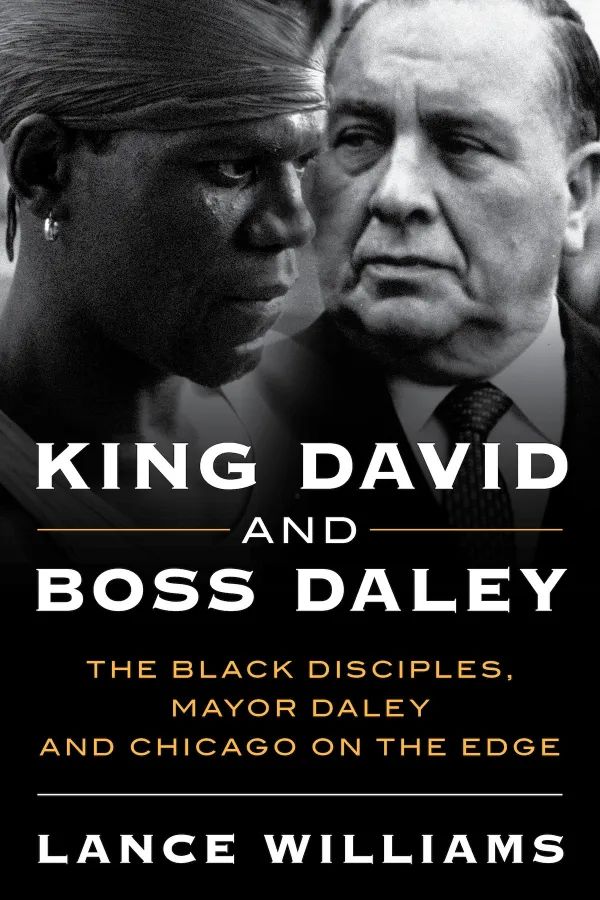

In a new book King David and Boss Daley: The Black Disciples, Mayor Daley and Chicago on the Edge, coming out in December , author and Northeastern Illinois University Professor Dr. Lance Williams traces the life stories of two of Chicago’s most powerful leaders: Black Disciples “King” David Barksdale and “Boss” Mayor Richard J. Daley. While Williams notes that the two never met in person, and many Chicagoans may not think of them together, Barksdale and Daley were on directly opposing sides of many of the city’s political battles throughout the 1960’s. Barksdale and Daley were both leaders of their own powerful organizations: Barksdale had the Disciples, later the Black Gangster Disciple Nation, while Daley had the Hamburg Athletic Club, and later the city’s entire Democratic Machine, including the CPD.

King David and Boss Daley book cover. Courtesy of Prometheus

As Williams writes in the introduction: “Behind the poverty, crime and violence, this story is about the struggle for power between two men of violence, one with a chance and a historical opportunity and one with a chance and nothing else. In the end, it is a story about the inevitable conflict between right and wrong. Black and white. And the Black inner city and City Hall.”

Through a variety of historical archives, government documents, first-hand interviews, and personal experience, Williams has created a masterful document of history that is an essential read for anyone interested in the city’s past and future. The book contextualizes the pressing issues that Chicago faces today, from the racialized structural violence that is the perpetuation of segregated ghettos and concentrated poverty offset by concentrated wealth, to the interpersonal violence that manifests in shootings.

Williams weaves the book’s narrative between the lives of Barksdale and Daley, but the story in terms of Chicago’s gang history starts with the Irish and other white ethnic gangs that were formed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These Irish gangs arose as a byproduct of the poverty and discrimination that Irish immigrants originally faced in Bridgeport—“Chicago’s first slum,” as Williams puts it—until the Irish assimilated into whiteness by becoming police and politicians, among other establishment, status quo-maintaining careers.

In the early to mid 1900’s, these white gangs played an essential role in Chicago’s machine politics, often using violence or the threat of violence to turn out or suppress the vote and to reinforce the city’s racial segregation. Daley was elected president of the Hamburg Athletic Club in 1924 at twenty-two, and he had been a member of the group since his early teen years. He was seventeen in 1919, when the Hamburgs were heavily involved in the deadliest anti-Black race riot in Chicago’s history, although Williams notes that it was never confirmed whether Daley himself took part in the violence. Williams portrays the events that started the race riot in tragic detail—including the death of Black teenager Eugene Williams at the whites-only 29th Street Beach, and the police collusion and inaction that contributed to the chaos that reigned in the city for weeks.

Chicago’s history with Black street gangs generally started later into the twentieth century, and those groups were often first created as a form of protection from attacks by the city’s white gangs and the police. In fact, some of the city’s racist white gang members became police officers later in life, as they aged out of the gang—part of the city’s Democratic Machine and its infamous patronage politics, a system where city jobs were exchanged for political support.

Both the white gangs and the police played, and continue to play, a key role in reinforcing the city of Chicago’s racial boundaries. To this day, the city remains one of the most segregated and heavily policed in the world, with more police per capita than almost any other city in the world, other than New York City. Yet Mayor Lightfoot and many City Council representatives, such as 2023 mayoral candidate and 15th ward Alderman Raymond Lopez, advocate for even more police as a solution to the city’s violence and the poverty and precarity that produces it.

David Barksdale was born to Virginia and Charlie “Rainy” Barksdale, Jr. on May 24, 1947 in Sallis, Mississippi. The Barksdales were sharecroppers in Mississippi, and they were not able to afford to move to Chicago until 1958—three years into Mayor Richard J. Daley’s first term. The Barksdale family first moved to Bronzeville, the city’s Black economic and social hub, until large parts of it were cleared as part of the city’s “urban renewal”—or as Williams writes, “Negro removal”—which displaced the family to Englewood, to make way for the new expressway that, like the projects, was built to segregate Black and white Chicagoans.

David Barksdale had a very rough and impoverished childhood, and he was kicked out of his house by his father when he was just fourteen, as a result of his disobedience. David was known early on in his life as a great boxer, and he was never afraid to defend himself when challenged. Barksdale was first sent to the “Audy home,” the city’s jail for children, at the age of just sixteen.

As the city’s population of poor Black people grew, so did the police budget and presence in those neighborhoods, which led to youth like David being frequently criminalized, harassed and arrested by the CPD. There was an eightfold increase in Chicago’s Black population from 1910-1940 during the first Great Migration, and the city’s white power structure was determined to protect their segregated turf and wealth. Throughout the middle part of the century, during Daley’s tenure, Chicago’s Black population grew again from 8.2 percent to 32.7 percent. At the same time, from 1945 to 1970, the city’s police budget grew 900 percent and the CPD more than doubled the number of cops on the streets.

Black youth growing up on the South and West Sides knew not to trust in or talk to the police, which remains justifiably true to this day. Williams details the robbery, extortion, harassment, torture, frame-ups, abuse, racism, shootings, and straight-up murders that Chicago police perpetrated on the city’s Black communities throughout the entire period of the book, from before 1919 to around 1972.

In the early 1960’s, Barksdale started to lead around a group of youth from his neighborhood called the 65th Street Boys, in order to protect himself and his friends from racially motivated attacks—such as the 1957 murder of Black youth Alvin Palmer by white gang member Joseph Schwartz in Englewood. Chicago police and politicians were doing nothing substantial to stop these racist murders and assaults, so Black youth like David had to figure out a way to defend themselves.

In 1963, after Barksdale’s time in the Audy home where he encountered other gangs, he and his friends decided to create a more structured gang called the Devil’s Disciples. The group did not become the powerful Black Gangster Disciple Nation until years later, when they grew and merged with Larry Hoover’s Supreme Gangsters during the peacemaking that was encouraged by the Black Power movement. However, in the early days of the Disciples (they quickly dropped the “Devil” from the name, largely because David didn’t like it), they proved themselves to be among the best boxers in all of the South Side. They had to be, in order to defend themselves against rival Black gangs like the Blackstone Rangers, and white gangs determined to defend their territory, including the Chicago Police Department, in Williams’ words.

The most crucial parts of the book take place in the 1960’s during the Chicago Freedom Movement with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the Black Power Movement, and the Illinois Black Panther Party with Fred Hampton. This is where the conflict between “King David and Boss Daley” becomes the most pronounced, as both MLK and Hampton organized and met with Chicago’s Black gangs.

Williams writes: “Mayor Daley had always been concerned about Black street gangs. But his concern wasn’t about them killing one another in their endless gang wars, nor was it about them terrorizing their communities. The mayor’s biggest concern was that Black street gangs like the Disciples had now added branches numbering several thousand and were starting to show signs of political and economic awareness.”

Daley’s own youth gang, or “athletic club,” the Hamburgs, had moved from fighting in the streets to politics and power, as Williams writes, and now Daley was worried the “young, tough Black males could be dictating who their Alderman would be if he didn’t stop them.” Daley felt especially threatened by the Black Panthers, “a more sophisticated, if smaller group” who were perceived to be even more dangerous than the gangs, due to their revolutionary politics. Williams writes, “The Disciples and the Black Panthers had set up a free food program in the ghetto and had opened a health clinic that was superior to those of own health department.”

Consequently, in 1967, Daley and the CPD leadership created the “Gang Intelligence Unit” to disrupt the political organizing of the Disciples, Stones, Panthers, and other like-minded groups. Daley’s next move was to hold a conference to attack the Black gangs in the eyes of the voting public. As Williams observes, however, “the meeting never acknowledged that youth crime was mainly a product of the evils in society like poverty, discrimination, and other unrighted wrongs. There was no mention of any of the positive efforts of these groups, like their attempts to have truces, job training, civil protest, and the like. They never offered solutions to help guide young people seeking constructive opportunities. It only focused on their so-called criminal activities. The mayor and the city agencies present never discussed its responsibility to aid such groups.”

Williams writes that, once Daley had sufficiently demonized the Black gangs, CPD ramped up their repression—especially when it came to the Black gangs’ political organizing. Several of the city’s largest gangs had called truces—such as the Lords, Stones, and Disciples (LSD) coalition—and they had done so in order to fight their real enemies in the city’s power structure, instead of fighting themselves. This was simply unacceptable to the CPD, who fought to sow discord between the gangs, in order to make it easier to incarcerate gang members and to justify the CPD’s own exorbitant funding and demand even more money from the city. As prominent Blackstone Rangers leader Mickey Cogwell told a reporter from the Atlantic in 1969: “the [CPD’s Gang Intelligence Unit]—black men—use the Rangers and the rivalry between us and the to make their work more important to the system.”

When Barksdale and the Disciples started a free breakfast program with the ultimate goal of ending poverty and hunger in Englewood, and leading protests against police brutality and discrimination—alongside their former rivals—Daley and the police ramped up the repression even further. Williams details the police attacking and breaking a strike when Barksdale and the LSD coalition protested against racial discrimination in hiring at city construction sites. Through subordinates, the Daley administration even denied that there was such discrimination in hiring, just like they denied the fact that there was slum housing in the city of Chicago when Martin Luther King Jr. came to town to protest those very slums. Homelessness, substandard, overpriced housing, and a lack of building management services still affects many people on the South and West sides today.

However, despite Daley and the police’s demonization of Black gangs, many people in Chicago’s Black communities knew their real enemy—and it wasn’t their sons, cousins, nephews, grandsons, and other family members who the police alleged were associated with gangs. Even when someone was killed by another person within the community, blame often fell on city leadership for creating the conditions that produced the violence, which remains justifiably true to this day.

Williams writes about the murder of Katie Stallworth in the Robert Taylor public housing projects: “The people of the projects knew that a person murdered Stallworth, but they blamed the ‘white power’ structure of Chicago, from the mayor’s office to the elected officials who had seen fit to designate certain areas in which to concentrate public housing. From the beginning, there was talk of the projects being the means to contain the Black population. It was widely known that wherever there is a dense concentration of people in a limited area filled with smoldering resentment, frustration, and despair, such crimes such as this and others will continue to happen.”

When Barksdale and the LSD coalition continued to press on with their civil rights activism alongside Fred Hampton and the Black Panthers, the police escalated their repression even further. Even though the gangs had called truces, their growing left-wing politicization made them dangerous to the status quo, so the CPD attempted to break up those truces—despite the fact that they were fostering peace, for a time. As Professor Toussaint Losier has written elsewhere, “the LSD coalition represented an attempt not only to win living wage employment and broader social transformation but also to work through each gang’s internal divisions by pursuing a vision that placed Black Power over gang empowerment.” However, Daley and the rest of City and police leadership did not want any social transformation along the lines of what the Black Power movement advocated—similar to how the current mayor does not want to disrupt the carceral status quo, especially during election season.

In 1968, Daley’s protege, Edward Hanrahan, became Cook County State’s Attorney in order to continue to go after the Black gangs and the Black Panthers, and he was given his own CPD unit to do so. Most infamously (yet still not talked about enough in Chicago), working with the FBI, State’s Attorney Hanrahan’s CPD unit murdered Illinois Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton and Peoria chapter founder Mark Clark on December 4, 1969. The same day as this assassination and subsequent coverup, prominent LSD leader and Black P. Stone Nation member Leonard Sengali was arrested for a crime that he did not commit and pressured to testify against fellow LSD members and other civil rights activists. Bobby Gore, spokesman for the Conservative Vice Lords and another LSD leader, was similarly arrested on murder charges despite claiming innocence. Several other LSD members and Black Panthers were similarly arrested on fabricated and trumped-up charges and pressured to testify against each other.

Black Gangster Disciple Nation leader Larry Hoover was later arrested and sentenced to 100-200 years in prison for murder, contributing to the fracturing of the Nation into the Black Disciples and the Gangster Disciples—which was made worse by David Barksdale’s death from kidney failure in 1974, and still persists to this day.

By 1972, Mayor Daley, State’s Attorney Hanrahan, and the CPD had defeated the David Barksdale and Black gangs and Fred Hampton and the Black Panthers—at least in terms of their ambitions for political power and civil rights gains, such as the ending of poverty and segregation in Chicago’s Black communities. The Black gangs still persisted—as they do today, despite the persistent efforts of the CPD to eradicate them—but the gangs fell into different rivalries and factions amidst the decades of worsening violence, poverty, disinvestment, deindustrialization, gentrification, privatization, school and mental health facility closings, and continuing police brutality and mass incarceration, among other factors.

The “War on Gangs” approach still persists to this day in the city of Chicago, because it was continued by subsequent mayors such as Richard M. Daley, Rahm Emanuel, and now Lori Lightfoot. As Bella Bahhs has written for the Triibe: “Today, when violence in Black and brown Chicago neighborhoods is categorized as ‘gang related,’ it absolves the city officials from taking responsibility for constructing racial ghettos and designated pockets of poverty.” Policing and mass incarceration are then presented as the only possible response to violence, because structural change—such as actually ending poverty and segregation—is unthinkable to the people in charge of maintaining the discriminatory and violent status quo.

These are all the policies that make up the “organized abandonment” of racial capitalism and the “organized violence” that it takes to manage capitalism’s inherent racialized inequality, in the words of abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore. These apartheid-like structures created wars and cycles of violence that are exceedingly difficult to resolve—especially with the easy availability of guns in America, the world’s leader in gun manufacturing and arms dealing, military and police spending, and overall incarceration. Tragically, these cycles of violence will likely persist as long as the conditions that produce such violence still govern the City of Chicago and the country: including entrenched segregation, poverty, widespread police abuse and incarceration, and widespread availability of guns.

Williams has written an essential document of history that explains how Chicago got to where it is today. Whether you are interested in political history, gang history, or just the city in general, King David and Boss Daley: The Black Disciples, Mayor Daley and Chicago on the Edge is one of the best books out there. While it is a tragic story filled with lots of death and oppression, it is also a story of perseverance and ingenuity in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, and it deeply resonates today. Black youth and especially Black “gang members” continue to be the most demonized population in the City of Chicago, and that fact can be traced directly to the events portrayed in this book.

Several decades of heavy-handed policing and mass incarceration have proven to be completely unable to eradicate gangs or resolve the problem of gun violence. As Williams and others have written for the Chicago Reporter, Chicagoans should “reconsider the ‘war on gangs’ strategy that has been Chicago policy since it was declared by Richard J. Daley in 1969.” There will only be peace when the people in charge of the city of Chicago, and the nation, make transformative structural changes to how the city and country operate; such as passing the PeaceBook ordinance, ending poverty and segregation, and divesting from the massive policing, incarceration, and military budgets to facilitate investment in true community resources like education, housing, healthcare, and much more—including Reparations for the historical and present harm caused.

Bobby Vanecko is a contributor to the Weekly, and is the great-grandson of Richard J. Daley. He previously wrote about this family connection in 2020.

Subscribe to the South Side Weekly to get the print edition in the mail. Issues are published every other week. For the past ten years, the Weekly has produced original, local reporting for the South Side of Chicago and distributed it for free in print and online. Reader support helps makes this work possible. Please consider making a one-time or recurring donation today.