Contemporary Pundits Need a Refresher on Populism’s History

The way “populism” is typically invoked in today’s media, you wouldn’t know that the word comes down to us from one of America’s most successful progressive movements— the grass-roots crusade that resisted corporate power and fought to save democracy 130 years ago.

Many of today’s pundits would have you think otherwise.

“Is American Democracy Doomed by Populism?” asks Yascha Mounk of the Council on Foreign Relations, writing days after Trump supporters stormed the Capitol. Politico called Trump “The Perfect Populist” in 2016, likening him to George Wallace, Alabama’s white-supremacist governor in the 1960s. “Trump and Sanders Lead Competing Populist Movements,” says the Washington Post, echoing a common claim that progressives share some kind of “populistic” perspective with the far right.

In this ahistorical babble, you rarely hear mention of the men and women who organized a multiracial resistance to the first corporate oligarchs.

“The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few,” the Populists announced when they formed the People’s Party in 1892. The mega-rich who “despise the republic and endanger liberty” were the real danger to democracy.

The People’s Party would contest the rule of these “plutocrats” at a time of rapid social change. Railroads, electricity, and mechanized crop harvesting were transforming the economy, making the “Robber Barons” who controlled these new technologies the richest men on earth. While many workers took home less than $10 a week in 1890, Jay Gould, the infamous stock speculator, was pocketing more than $20,000 a day (in today’s dollars, about $700,000).

Farmers were routinely abused. Railroad monopolies gouged them with inflated charges for shipping wheat and cotton to distant markets, while lenders (especially in the South) extorted interest of 40% or more on loans for overpriced supplies and equipment. At a time when farmers and farm laborers accounted for more than 40 percent of the labor force, their collective anger posed a genuine threat to unfettered capitalism.

Neither the Democratic nor Republican parties saw what was coming. Both were dominated by monopoly capitalists who wanted minimal taxation, no regulation of their “private” business empires, and no legal rights for the farmers and workers who resisted corporate profiteering. At a time when there were no primary elections for choosing a party’s presidential candidate, there was little prospect for internal reform in either major party.

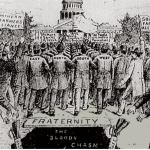

The Populists had to launch a new political movement, drawing support from the Farmers Alliance, the American Railway Union, the women’s suffrage movement, Christian Socialists, the United Mine Workers, and utopian reformers. The People’s Party was also a multiracial movement in the South, where African Americans served on the party’s state executive committees in Texas, Louisiana and Georgia.

The economic and political goals of these Populists were as broad as their membership. They wanted farmer-owned cooperatives that would negotiate for better prices from processors and merchants. They favored public ownership of railroads, utilities and other natural monopolies. They called for postal savings banks and low-cost federal loans for farmers and workers. They wanted recognition of farm organizations and labor unions. Where bankers favored the high interest rates that came from basing the money supply on scarce reserves of gold, the Populists wanted to abolish the Gold Standard and expand the money supply with government-issued bills and silver coinage.

Above all, they wanted to restore a democracy corroded by the blatant buying of privilege. Nationally, they favored the election of senators rather than their appointment by bought-and-sold state legislatures— as was then the case. To reform state government, they called for referendum, recall, and votes for women. In the South, they favored political rights for Black voters.

On this reform platform, the Populists called on the “producing classes” to vote for the return of government “to the hands of the ‘plain people’.”

They failed nationally, but it was a close call in the West, the Great Plains and the South. Fifty Populists won election to Congress from 16 states. North Carolina, Oregon, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado all elected Populist governors. The Populist vote would have been higher still in the many southern states where white elites organized a deadly backlash, stealing votes, murdering Populists, and imposing one-party rule by white-supremacist Democrats.

Even so, the Populists transformed the political terrain in America, marked by the subsequent emergence of progressive movements in both national parties. The watershed was 1896, when William Jennings Bryan won the Democratic Party nomination for president on a pledge to regulate the railroads and expand the money supply with silver. Running as a Democrat— and widely viewed as a “Popocrat”— he fell short with 47 percent of the popular vote. But progressives thereafter gained ascendency in the party, leading to reforms in the next century that included much of the Populist platform: election of senators, votes for women, corporate regulation, collective bargaining rights for workers and farmers, and an end to the Gold Standard.

Bernie Sanders, the Democratic Socialist, is at least a distant cousin of these original Populists. Donald Trump is not. Even the phrase “right-wing populism” is— historically speaking— an oxymoron. The Populists of the 1890s would have despised the likes of Trump, a preening billionaire allied with today’s mega-rich.

Mainstream pundits would nevertheless have us believe that any popular movement calling on “the people” to overturn “corrupt elites” is a populist threat to democracy. Lumping Sanders together with a wanna-be fascist like Trump implies that both men seek to sway voters with equally polarizing and manipulative rhetoric.

Those who apply this shape-shifting term are actually branding themselves. Some are simply unwitting users of a phrase that’s in vogue and gives the appearance of historical insight. Others may know better, but have gotten used to it. Still others deliberately use the populist label to stigmatize any movement that challenges the questionable legitimacy of our elite-dominated “meritocracy.”

Elites who tar their critics in the U.S. with the sly pejorative of “populist” count on our collective amnesia. They’d rather the real Populists remained forgotten, along with the potential they represented.

Steve Babson is a labor educator, union activist, and history PhD living and working in Detroit. He is the author of the just-published Forgotten Populists: When Farmers Turned Left to Save Democracy.