‘Immensely Invisible:’ Women Fighting ICE’s Inaction on Sexual Abuses

When 23-year-old Mari walked out of the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention in 2022, she felt invisible. It was barely a month after she had entered the United States as an asylum seeker from Venezuela. The once vivacious bodybuilder now felt like she didn’t matter.

“When I looked at myself in the mirror, I felt like I didn’t deserve to wear nice clothes or to put on makeup or look good. I felt so immensely invisible,” Mari said.

Her time inside ICE’s Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia, between December 2021 and January 2022, left a deep mark on her self-worth. A year and a half later, it continues to wake her up in the middle of the night, shivering and in tears.

Mari is not her real name. We’re using it to protect her identity. She is one of five women who complained of being sexually assaulted by a male nurse who worked at Stewart.

Escaping from political violence in Venezuela, Mari arrived in the U.S. in late December 2021. She was arrested by Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) after crossing the border and then quickly transferred to Stewart. Shortly after, she went into the infirmary for a routine check-up. There, Mari encountered the nurse for the first time. He was a short, middle-aged white man with a short beard.

The nurse asked her to follow him into a small room and closed the door. When Mari was alone with him, she felt uneasy. After a few routine medical questions, he said she was pretty. He asked her if she had had any surgeries in the past. When Mari informed him of her breast surgery, he got excited and began staring at her breasts. And then he asked her to lay down on the examination table.

“He pressed my hand against his penis. When I tried to take my hand away, he began masturbating with it. I was devastated,” Mari said.

Weeks before, another asylum seeker from Venezuela, who we will call Viviana, said she faced a similar experience. Viviana has accused the male nurse of sexually assaulting her on two occasions.

“He asked me to lower my pants and placed the stethoscope down there,” Viviana said. “He would make lewd faces while doing that. I froze and stared into the void. I couldn’t understand why he did that to me.”

There are several laws meant to protect immigrants detained at ICE facilities from sexual assault and abuse. The primary law that offers this kind of protection to incarcerated and detained people is the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA).

After learning about PREA, Viviana, Mari, and two other women filed an administrative complaint with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) —ICE’s supervisory body— in July 2022.

The complaint, first reported by The Intercept, stated that the nurse had “repeatedly taken advantage of his position as a medical professional to isolate women at Stewart in private medical examination rooms, to force or coerce them into giving him access to private parts of their body without medical justification or need and assaulting them during his ‘medical exams.’”

Apart from these four women, public records confirm that a fifth woman has also made similar allegations about the same male nurse.

A broad pattern of sexual abuse in ICE detention

There is a pattern of sexual abuse complaints in ICE detention that goes beyond the Stewart facility and the accused nurse. Official records and testimonies obtained by Futuro Investigates – not reported previously — show disturbing details of 308 sexual assault and sexual abuse complaints filed by immigrants detained in ICE facilities nationwide between 2015 and 2021.

One of the complaints was from a woman who accused two ICE guards of raping her when she was detained at the East Hidalgo Detention Center in Texas. An unnamed person sent an email complaint to the DHS on behalf of this woman, who had been transferred to another detention facility in Louisiana at the time.

A transgender woman held in another facility in Texas said men she was detained with forced her to perform oral sex. When she complained to ICE officers, they ridiculed her. No one registered her complaint at that facility. She couldn’t file a complaint until she was transferred to another detention center.

A woman detained in Colorado said an ICE guard sexually assaulted her. The guard commented about her breasts and told her he would “let her go free if she had something to do with him.”

He told her that otherwise, she would be denied asylum and get deported, the woman said. The officer allegedly asked for her address and said he would look for her if she were released.

In Colorado, a man complained of being sexually assaulted by an ICE officer. The officer, the man said, touched his genitals and mocked him in front of his high-ranking sergeant.

The complainant also alleged that the high-ranking sergeant told him, “Are you going to cooperate or are you going to make charges?”

Later, the complainant said that the sergeant threatened him by saying: “I can deport you to Juarez, Mexico right now. I have an airplane right here. Nobody knows where you are, and if you try to escape, it will go very badly for you because there are five of us here.”

At least five complaints in the records allege that ICE employees threatened them with deportation.

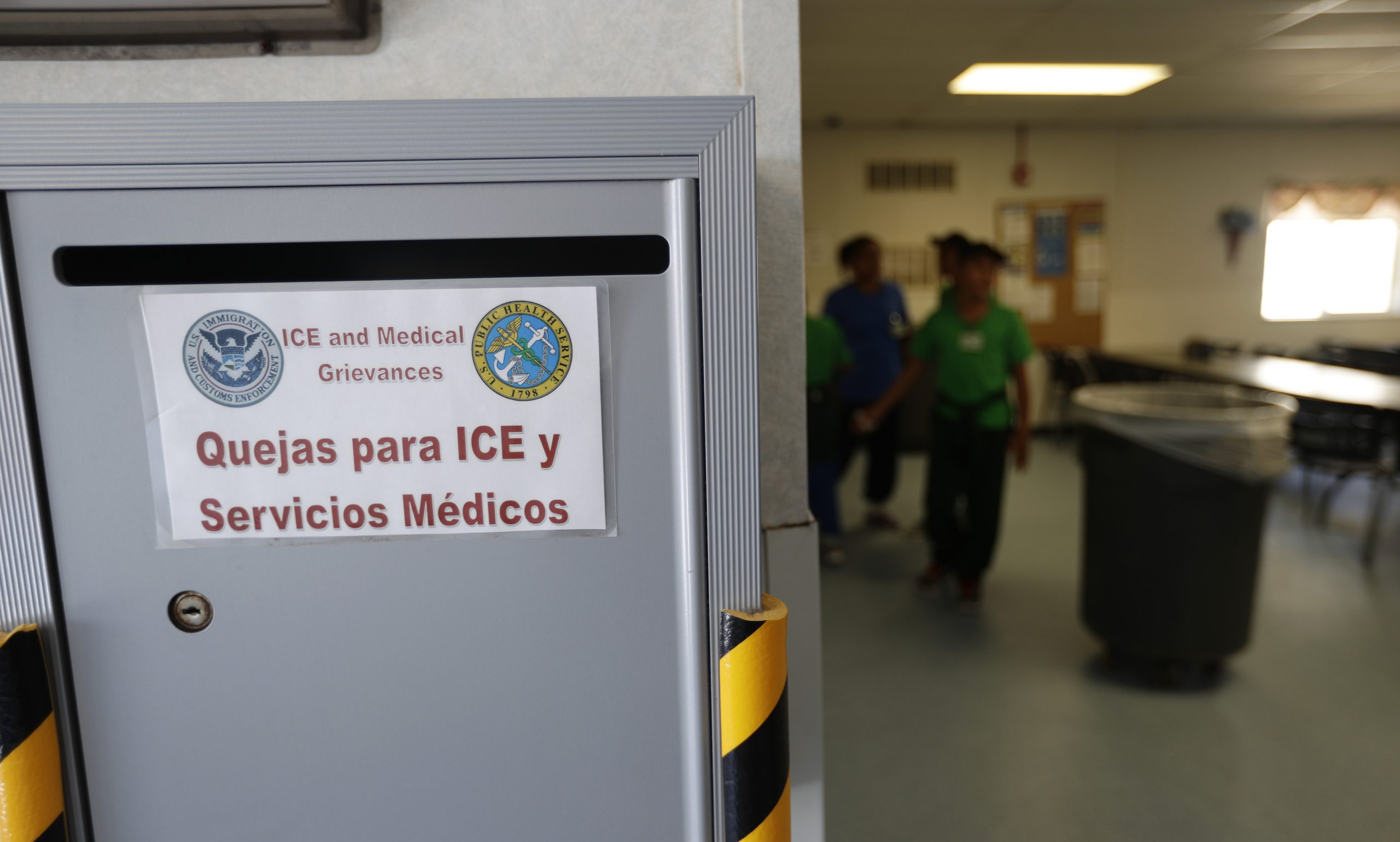

A box for grievances is seen in the cafeteria at the ICE South Texas Family Residential Center.(AP Photo/Eric Gay)

It is difficult to decipher whether ICE took any action after the complaints were filed and whether the allegations were investigated, as the records we obtained are heavily redacted. In most complaints —about 60%— columns on current activity are left blank.

The data obtained by Futuro Investigates reveals a disturbing trend beyond Stewart, the detention center where Viviana and Mari were detained and allegedly abused. This trend shows that detention officers, contractual guards, and ICE employees are accused of sexually assaulting the individuals they are meant to protect. According to the obtained data, more than half of all abuse allegations made in the past six years were directed against staff.

A closer inspection of the data reveals allegations of similar patterns of abuse by authorities: intrusive pat-down searches, open shower areas, groping and invasive touching of genitals and the use of solitary confinement as a retaliatory measure to deter detainees from following up on their complaints.

Over the past two years, Futuro Investigates interviewed at least a dozen immigrants complaining about their time in detention. The patterns of abuse reflected in the data also emerged in several of their allegations, illustrating how this is a systemic issue.

In those interviews, immigrants who don’t know each other and were held in different detention centers have mentioned similar fears of deportation and have similar accounts of how they have been facing different forms of retaliation —from solitary confinement to revocation of privileges.

In one interview, a 29-year-old asylum seeker from Nicaragua detained at the Jackson Parish Detention facility in Louisiana alleged that she was physically abused and beaten up by multiple ICE guards because she resisted sexual abuse.

The woman alleged that she witnessed how one ICE officer had sexually abused her friend by pressing her breasts under the garb of a pat-down search. She said the ICE officer was “known to do this to women.”

When it was her turn to be patted down, she refused, and that angered the officer, who later beat her up. “I said no and he got pissed off that I did not allow him to touch me, and that’s why I think he physically attacked me later,” she said.

After being physically attacked by the ICE officer and other guards, the woman said she was placed in solitary confinement as punishment. Futuro Investigates reviewed a Civil Rights complaint filed by her with Homeland Security about these allegations.

In another interview, a 21-year-old woman detained first at Glades County Detention Center and later transferred to Baker County Detention Center in Florida talked about open showers and sexual voyeurism by guards at both facilities.

“The shower is like, everybody can view you. Because all of the showers, every last one of them, is open, you can literally reach over and touch the person. You can reach over and grab them. And we could see the guards in their guard tower staring at us,” she said. This young woman also filed a complaint with DHS detailing these allegations.

The aftermath at stewart detention center

The male nurse Mari, Viviana and three other women accused of sexual abuse had worked at Stewart since at least 2018. According to internal medical records reviewed by the advocacy group Southern Poverty Law Center, he was allowed access to female detainees until at least mid-July 2022, months after the women were allegedly assaulted.

Following the complaint, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation launched a criminal probe into the alleged sexual abuses in 2022. Earlier this year, a spokesperson from the Bureau confirmed to Futuro Investigates that the investigation concluded and was submitted to the Georgia District Attorney’s office.

Women work in ICE detention while they wait to clear their legal status. (AP Photo)

In August 2022, the nurse was placed on administrative leave. Another complaint was also filed with the Georgia Bureau of Nursing. His license has not been revoked at the time of publication. Its investigation is pending.

Futuro Investigates has called and left multiple messages to the accused nurse, but he didn’t answer.

It’s been a year since Viviana, Mari, and other women spoke up and filed their complaints. None of them have heard anything about the outcome yet.

The Lumpkin County DA’s office in Georgia, which is supposed to decide whether to pursue charges, did not respond to our questions. ICE and CoreCivic, the private company that manages Stewart Detention Center, have denied our requests for an interview on this subject.

“It has been a very opaque process,” said Erin Argueta, from the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). “No one at any (government) level has responded to requests for more information, responded to questions from the women about the next steps or what is happening with the complaint or the investigation.”

Argueta was Viviana’s attorney. She was among the first lawyers to learn about the sexual assault allegations at Stewart. She and other advocates at SPLC were instrumental in drafting the sexual assault complaint on behalf of the women.

Argueta fears many other complaints don’t get reported. “It took an amazing amount of bravery for these five women to come forward,” she said. “Sadly, I think there are numerous other people that will never publicly tell their story because of the threats and fear of retaliation.”

For years, Stewart hosted only male detainees, so the nurse couldn’t access immigrant women. The center began holding women in late 2020, a year before Viviana and Mari were transferred there.

In 2020, another notorious Georgia detention facility, the Irwin County Detention Center, was shut down following a whistleblower’s complaint that exposed non-consensual hysterectomies of female detainees by a gynecologist.

The women who were detained at Irwin were transferred to Stewart. Even before the transfers, Stewart had a documented history of abuses, including allegations of medical negligence, sexual abuse, racism and the use of force and pepperspray to control detainees.

Advocacy groups often refer to Stewart as “the deadliest detention center in the U.S.” Since 2017, nine detainees have died there, the highest number of deaths reported in any detention facility nationwide. Two of them committed suicide.

It is also one of ICE’s largest facilities, currently holding 1,600 detainees —according to federal data compiled by the Transaction Record Analysis Center.

Public records from Homeland Security – obtained by The Intercept and also reviewed by Futuro Investigates – along with ICE’s own Facility Inspection report show that, in addition to Mari, Viviana, and the three other women who have alleged sexual assault by the male nurse, there were at least six other complaints of sexual abuse made inside Stewart between 2021 and 2022.

A cloak of secrecy

In 2003, the U.S. signed the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA). PREA is the law aiming to protect incarcerated and detained people from sexual assault. It took 11 years to fully implement PREA in all immigration detention agencies, including ICE, in 2014. In the U.S., the immigration detention system is completely independent of the criminal justice system, and immigrants have no legal status in detention — so they have no right to free legal representation, for example.

Today, ICE claims it thoroughly implements PREA and has “zero tolerance for all forms of sexual abuse or assault.” Our reporting shows that most sexual abuse complaints aren’t being investigated. Of the 308 complaints we received in the records, only 40% of cases triggered any action as per the information we’ve received in the data.

“It’s likely that that number [308 complaints] only scratches the surface, because ICE operates under a cloak of secrecy and rarely publishes comprehensive data on complaints,” said Layla Razavi, the interim co-executive director at Freedom for Immigrants, a nonprofit based in California focusing on stopping immigration detention.

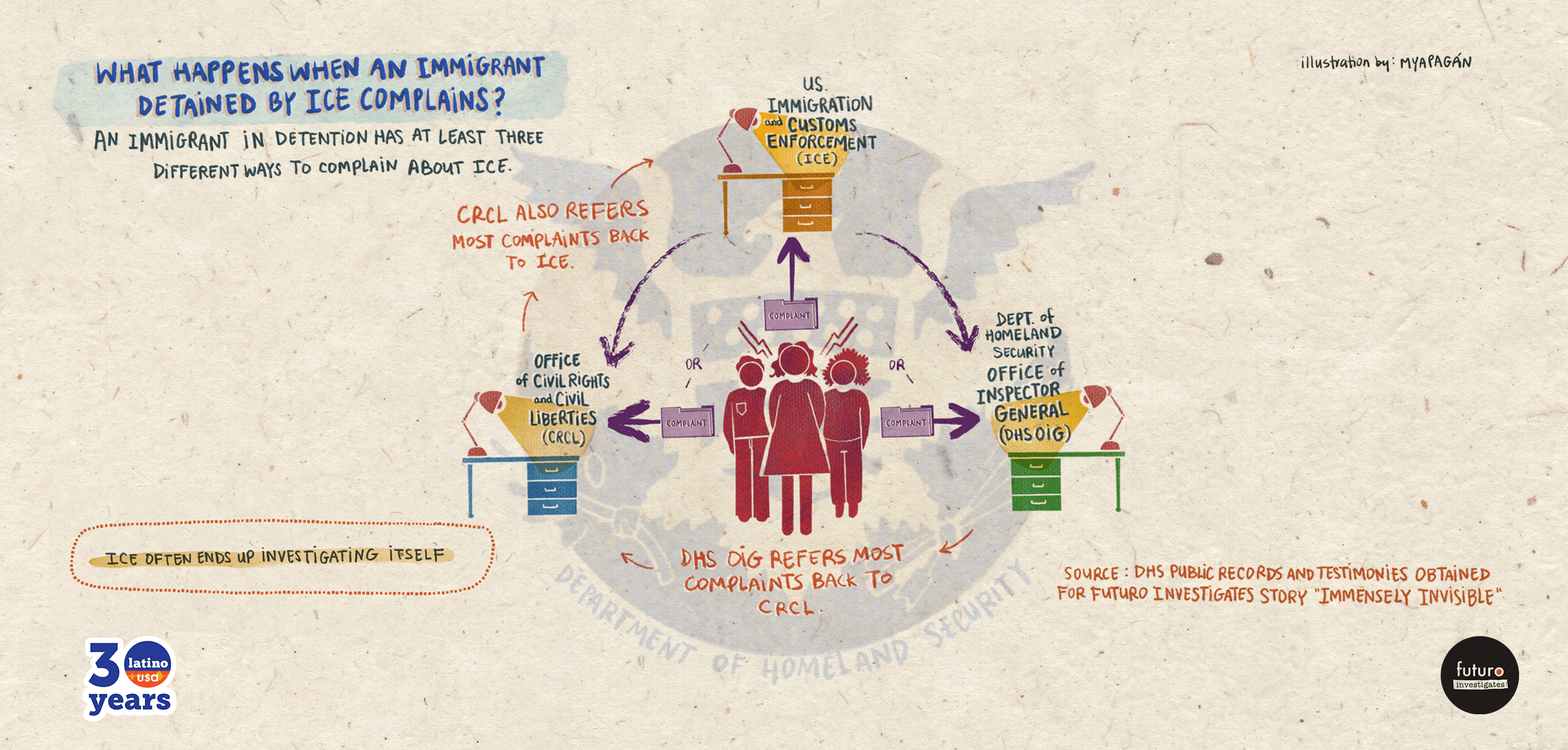

She explained the complicated bureaucratic path of an abuse complaint to return to ICE.

Image Credit: Mya Pagán, Instagram: @myashi

ICE is supposed to send all complaints to the Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL), the oversight body under Homeland Security that is supposed to investigate the allegations. This Office then refers the cases to the Office of the Inspector General (DHS OIG), the ombudsman overseeing all departments at Homeland Security.

The DHS OIG, in turn, sends most of the abuse complaints back to CRCL to probe.

“CRCL may investigate them on its own, but we’ve seen that in the majority of cases, CRCL sends it back to ICE. So it’s like ICE investigating ICE. And we never get the whole picture,” Razavi said.

Between 2010 and 2016, DHS recorded at least 33,000 instances of physical abuse and sexual assault —primarily committed at ICE and CBP facilities. Less than 1% of these complaints were investigated, according to federal data shared in 2018 with Freedom for Immigrants.

Today, ICE ERO, the arrest and deportation branch of ICE, operates nearly 100 detention centers across the country. Most are run by private prison companies like CoreCivic, which manages Stewart Detention Center, where Viviana and Mari said a male nurse abused them.

Protecting immigrants in detention

The PREA rules, the law protecting detainees and incarcerated people from sexual abuse, are also meant to safeguard victims from retaliation after they file an abuse complaint. They ensure that all complaints are recorded and investigated.

Over seven years after fully implementing PREA on paper, ICE has reportedly failed to follow its guidelines, according to multiple federal complaints filed by advocacy groups and testimonies of complainants such as Mari and Viviana.

While still detained at Stewart in early January 2022, Mari exercised her right to report sexual abuse under PREA.

She informed ICE and CoreCivic staff about what the accused male nurse allegedly did to her.

What followed were days of what she described as a “constant interrogation.” She was asked to repeat the details of the assault. Mari alleged that ICE and CoreCivic staff called her a liar and threatened her with seven years in prison.

“They asked me almost every day: ‘Are you still sure this happened?” Mari said. “They manipulated me and said I was lying and that I could get seven years in prison.”

Another woman who was detained at Stewart and joined the complaint echoed Mari. We are calling her Laura to protect her identity.

Laura said she complained internally while detained, following PREA guidelines, but the guards also told her she would be imprisoned for seven years if she lied.

ICE and CoreCivic found two of those complaints “unsubstantiated” and one “unfounded.” Immigration lawyers and analysts say only a few complaints are “substantiated,” or found to be accurate, after a probe within ICE’s internal review system.

Private prison companies: an added setback for accountability

Detention facilities operated by private prison companies — like Stewart Detention Center — have another layer of intermediaries, making accountability even more difficult.

“It’s already a challenge to get ICE to do anything and investigate its own employees,” said Razavi from Freedom for Immigrants. “So when it comes to exercising that type of accountability over a private entity, it’s that much harder to really get transparency for what’s happening or any type of reform or change.”

When President Joe Biden took office in 2021, he signed an executive order phasing out privately-managed federal prisons. Companies like CoreCivic, which operates Stewart, can still manage ICE facilities.

CoreCivic is the largest owner of private prisons in the country. Its latest annual report shows that it makes more than a billion dollars from public money — more than half a billion stemming from running detention centers like Stewart.

“The profit model is essentially making money off of the bodies of black and brown immigrants,” Razavi said. “So every time a person is picked up and put into an immigration detention center and held in that prison, that company turns a profit.”

CoreCivic does not mention sexual and other abuse complaints to its investors in its 2022 annual report.

Futuro Investigates asked CoreCivic about the sexual abuse allegations made by Mari and other women about the male nurse. The company’s public affairs manager, Brian Todd, wrote in an email: “If a detainee is found to be at substantial risk of imminent sexual abuse, immediate action is taken to protect the individual. Any potentially criminal allegation of sexual abuse is immediately referred to law enforcement and shared with our government partner.

Mari rejected that claim. “All CoreCivic has done is hide and lie,” she said.

This is not the first time a CoreCivic-run facility has received sexual abuse complaints. In August 2022, three female detainees at the Ota Mesa detention center in San Diego, California filed a lawsuit alleging that a CoreCivic guard forced them to perform sexual acts, assaulted them during strip searches, and groped them while they slept.

The Ota Mesa facility was also accused a year prior in an ACLU report titled “CoreCivic’s Decades of Abuse,” which cited 19 reported incidents, in 2019 alone, of an employee on-detainee sexual abuse.

Over the last year, since they filed the joint complaint, Mari and Viviana have gotten closer, becoming each other’s support system. They’ve both battled post-traumatic stress disorder triggered by their experiences at Stewart Detention Center.

When Viviana got out of detention last year, her family could sense she wasn’t who she used to be. She turned quiet and wouldn’t speak much. For the last year and a half, she’s had to undergo psychiatric treatment and still suffers from frequent nightmares.

“My family told me that I was out of my mind,” she said.

Viviana recently gave birth to her first child. Her baby girl has brought much-needed calm and hope, but she awaits justice.

“It is an indescribable feeling. it does not have a definition. I believe my daughter arrived to calm many things that were not well with me,” she said.

Mari has developed facial paralysis due to stress, which her doctor said could be due to her trauma. Despite the mental health and physical challenges, she remains indomitable. She participates in protests demanding the shutdown of Stewart and all ICE facilities.

“What is going to motivate me more than me telling them, ‘Hey, I’m here. I was the one that you did this to. But look at me. Here I am. You didn’t kill me. Here I am,” she said.

*Maria Hinojosa, Sofía Sánchez, Roxana Aguirre y Roxanne Scott contributed to this investigation.