A Century After Its Founding, the Israeli Communist Party Is at a Crossroads

One-hundred years after it set down roots between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, the Communist movement in Israel, once the leading current of the Palestinian political struggle for equality, is at a potential crossroads.

Establishing the Arab-Jewish Democratic Front for Peace and Equality (Hadash/Al-Jabha) in 1976 was a historic accomplishment for the Communist Party of Israel, commonly known by its Hebrew acronym, Maki. Hadash signified the party’s prominence among Palestinian citizens, affirmed its commitment to joint Arab-Jewish political action, and became its most visible public face.

In May 2023, Hadash chair Ayman Odeh, arguably the most statesman-like national political figure from any party, announced he would not run in the next Knesset election. Hadash regulations require anyone who has served eight years in the Knesset to be endorsed by ¾ of the Council members before seeking another Knesset term, and Odeh did not appear to have the votes.

Odeh was the leading architect of the now-defunct Joint List, comprised of entirely and predominantly Arab parties, whose strength peaked at 15 Knesset seats in 2020. The Joint List won’t be resurrected. Odeh’s departure from the Knesset therefore offers an opportunity to affirm the value of democratic governance, assert that the Knesset may not be the most important arena for organizing for political change, and open up a vital discussion about the future of Maki and Palestinian politics in Israel.

Throughout its history, Maki has been more thoroughly committed to Palestinian-Jewish equality and joint Palestinian-Jewish political action than any other political force in the country. That is an achievement to celebrate in a political environment defined by the severe constraints on left-wing political action imposed by the Zionist project and its alliance with its imperial patrons: successively, Britain, France, and the United States.

Ayman Odeh speaks during a debate in the Knesset plenum, Jerusalem, June 13, 2022. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

Nonetheless, despite years of mass support from the Palestinian public in Israel, over the course of its 100-year existence, Maki has manifestly failed to unite Arab and Jewish workers in Palestine-Israel into a viable socialist movement. It committed serious political errors and misunderstood the circumstances in which it acted.

Like all communist parties, it apologized for the crimes of Stalinism and adopted an undemocratic organizational structure. After the establishment of the State of Israel, following the lead of the Soviet Union, Maki minimized its critique of Zionism as a settler-colonial project. It did not adopt the Palestinian view of Israel as an apartheid regime. Like most Israeli parties, it has rarely acknowledged the full significance of the issues of gender equality and the structural subordination of Mizrahim.

Communist theory anticipated that the Jewish working class in Palestine would participate in a struggle for socialism and be a major force in the anti-imperialist struggle against British rule. But recently implanted settler-colonial working classes who perceive themselves as politically more “advanced” than indigenous populations have never constituted a stable social base for internationalist socialist politics. The working class of the yishuv (the pre-state Zionist settlement in Palestine) was overwhelmingly loyal to Zionism and, for the most part, its alliance with British imperialism.

The leaders of the Mandate-era Palestinian national movement were primarily socially conservative urban notables and large landholders who dominated the peasant majority. By the time of the Great Arab Revolt of 1936-39, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husayni, who initially owed his prominence to a British appointment, emerged as the titular head of the Palestinian national movement.

The incompatibility of the Zionist loyalties of the great majority of the Jewish working class, and the social character of the leadership of the Palestinian national movement made any alliance between them improbable. This has been the defining problematic of communism — indeed all progressive political action — in Palestine-Israel ever since.

Inherent contradictions

Maki’s historical trajectory was shaped by reciprocal and asymmetrical relationships between worldwide political developments, local and regional labor movements, and anti-imperialist struggles.

Communism emerged in Palestine as a movement of a small group of radicalized Ashkenazi Jews who had recently arrived as Zionist settlers. Inspired by the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, they sought to align themselves with the Communist International (Comintern) established in 1919 under the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Following four years of ideological debates and a tortuous series of splits from the socialist-Zionist Left Po‘alei Tziyon (Workers of Zion) Party, these pro-Comintern Jewish immigrants gradually renounced their Zionist and quasi-Zionist positions.

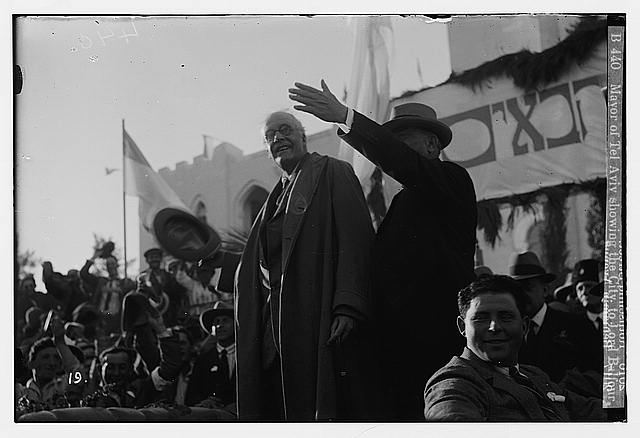

The Mayor of Tel Aviv showing the city to Lord Arthur Balfour, April 1925. (Library of Congress)

The new communists easily agreed on opposing British imperial rule and its alliance with Zionism enshrined in the 1917 Balfour Declaration. However, they were ideologically divided on three main issues: how should communists relate to working-class Jewish settlers? Would Jewish immigration and Zionist construction create conditions conducive to the growth of socialism? And how should communists relate to the emergent Palestinian Arab nationalist movement and its conservative leaders?

By July 1923, sufficient unity on these questions was achieved to convene the founding Congress of the Palestine Communist Party (PCP). Its commonly used Yiddish name, Palestinishe Komunistishe Partei, reflected the party’s social base and marginal status in the country. The PCP resolved that Zionism was “a movement which contains the aspirations of the Jewish bourgeoisie” allied to British imperialism. This flawed analysis could not explain why the great majority of Jewish workers in Palestine supported Zionism. It was nonetheless sufficient for the Comintern to accept the PCP’s application for membership in March 1924.

Four months later, Karl Radek, head of the Comintern’s Eastern Section, wrote with concern to the Third Congress of the PCP: “Until now, the party was composed of immigrant Jews. In the future, it must become a party of Arab workers to which Jews can belong who have acclimated and rooted themselves in the Palestinian conditions, people who know Arabic.”

This would have been a formidable task even if the worldwide upsurge of socialist and anti-imperialist revolutionary movements anticipated by the Comintern had succeeded. However, in light of their defeat in places such as Germany, Italy, Iran, China, and elsewhere, doing so was certainly beyond the reach of a small, new political formation comprised overwhelmingly of Russian and Yiddish speaking Jews, some of whom were not yet fluent in Hebrew, let alone Arabic. Yet internationalist discipline required the PCP to accept the Comintern line, and, after its dissolution in 1943, the less formal version of pro-Soviet loyalism embodied by the Cominform.

Still, the PCP’s political action remained initially concentrated within the Jewish working class, which was largely organized under the General Federation of Hebrew Labor in Eretz Israel — commonly known as the Histadrut — on the exclusionary Zionist principle of Hebrew labor (“avodah ivrit”). As internationalists, the communists opposed this principle, leading Histadrut leaders to ban them from participating in the organization in 1924. The British Mandate authorities had already banned the PCP altogether in 1921.

Throughout the 1920s and 30s, there were very few Arabs among the party’s roughly 300 members, while the Palestinian Arab working class was still in its formative stages. A dozen Arabs were sent to Moscow for political education between 1925 and 1930, but only four returned to become party leaders; one died fighting for the Republic in the Spanish Civil War.

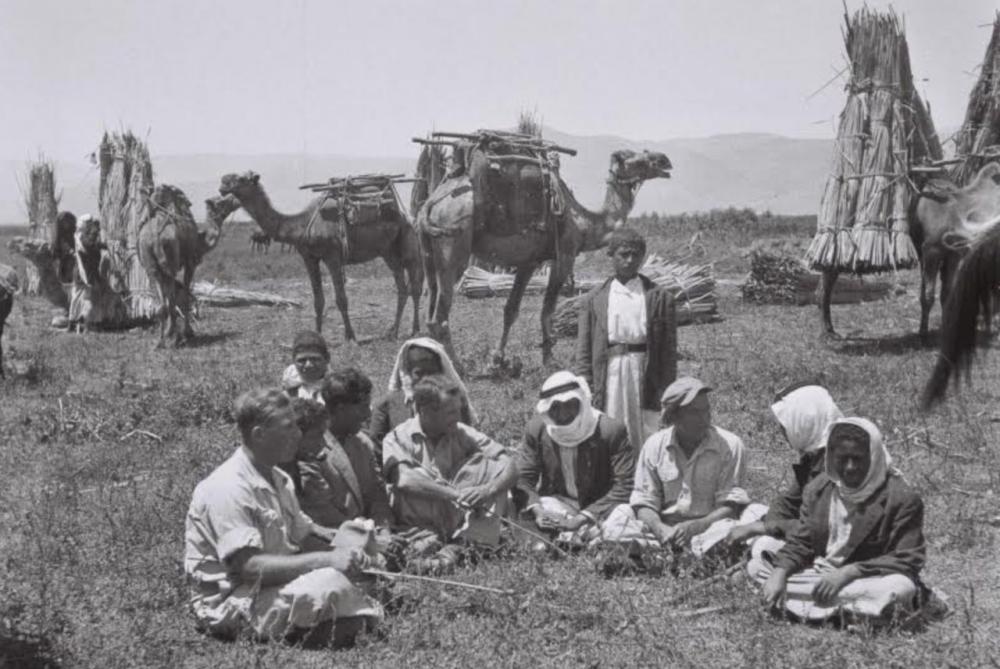

Palestinian farmers and their Jewish neighbors in the Lake Hula area, northern Palestine, 1946. (Zoltan Kluger/GPO)

The potential for Arab-Jewish unity and broadening the PCP’s Arab constituency was continually undermined by a complex of factors, including the structure of a settler-colonial society that awarded privileges to Jewish workers over Arabs; Jewish communists’ inability to extricate themselves from their social location in the yishuv; the alliance of Zionism with British imperialism that lasted until the 1939 White Paper; and the reactionary leadership of the Palestinian national movement, which disastrously misread the post-World War II global political map.

Moreover, from the mid-1930s on, a substantial proportion of Jewish workers and kibbutz members embraced the Zionist leadership’s aggressive security doctrine, which helped the British crack down on the Arab Revolt and would later shape the policy of the State of Israel. These impediments were exacerbated by the international communist movement’s Stalinist personality cult which made it impossible to distinguish between European and local political dynamics and the state interests of the Soviet Union.

The PCP’s inherently contradictory condition was manifested during the Arab Revolt, when some Arab party members interpreted the anti-fascist united front policy adopted by the Comintern’s Seventh Congress as authorization to join the guerilla bands that attacked both British forces and Jewish settlers. Jewish members rejected this approach. Some even believed that the Comintern’s line authorized collaboration with left-Zionists.

Ethno-national split

The onset of World War II transformed Palestine into a British logistical and military-industrial base. The Arab working class grew rapidly, reaching approximately 100,000. Communists emerged as an important force in the Arab trade union movement.

The Histadrut vied with two other major workers’ organizations — the Palestine Arab Workers Society (PAWS) and the communist-led Federation of Arab Trade Unions and Labor Societies (FATULS) — to organize Jewish and Arab workers employed in the British military camps and manufacturing and logistical facilities. In May 1943, without consulting with either of the Arab unions, the Histadrut called a strike to demand that a cost-of-living-alliance previously granted to other government workers be applied to the camp workers. Rejecting the Histadrut’s claim to speak for Arab workers, both Arab union federations opposed participating in the strike; only a small number of Arab workers joined in.

The PCP’s Arab leaders likely also opposed the strike because they saw it as an impediment to the war effort, a position common to communist parties in Allied countries during World War II. Some Jewish PCP leaders who advocated that the party should moderate its critique of Zionism and cooperate with left-Zionist forces, at least on trade union and labor issues, thought that Arab workers ought to have participated in the strike. That difference brought the tensions in the party, which had been escalating since the Arab Revolt, to the breaking point.

The Scots Guard regiment of the British army marches along Bethlehem Road outside the Old City of Jerusalem, 1936. (Library of Congress)

In response, a group of younger Arab intellectual PCP members issued an Arabic-language leaflet in the name of the party’s Central Committee, which had not approved it. They asserted that the party had purged the “Zionist deviationists” from its ranks and defined the PCP as “an Arab national party in whose ranks there are Jews who accept its national program.” The leaflet welcomed the recent dissolution of the Comintern, which would allow broader Arab national elements to join the party.

A series of mutual expulsions ensued, and the PCP disintegrated. The social motor of the split was the consolidation of a sizable Arab working class alongside a young, urban Arab intelligentsia, disproportionately composed of Christians from families lacking high social status. They formed left-leaning associations like the League of Arab Intellectuals, the People’s Club, and the Rays of Hope Society. Ironically, Palestinian communists most successfully participated in the political life of the Arab and Jewish communities only after this split in the PCP.

Communists led the fusion of the left wing of the PAWS and FATULS to form the Arab Workers Congress (AWC — known also as Ittihad al-Ummal al-Arab in Arabic), which by 1945 claimed 20,000 members. The AWC was the leading Arab trade union federation in Jaffa, Gaza, Jerusalem, and Nazareth and had a presence in the leading industrial center of Haifa as well, providing a social base for the new left-wing Arab political formation that emerged after the demise of the PCP.

In September 1943, leftist intellectuals and trade unionists, former PCP members, and others met in Haifa. At first, they sought to establish an all-Arab communist party. By early 1944, they established the anti-imperialist National Liberation League (NLL — Usbat al-Taharrur al-Watani), appealing to broad nationalist sentiment, as communists were then doing in several Asian and European countries.

A major achievement of the NLL was the establishment of an Arabic weekly, “Al-Ittihad” (The Federation or Union), in May 1944, formally as the organ of the left in the Arab trade union movement. Former PCP members Emile Tuma, Emile Habibi, and Fu’ad Nassar, a leader of the AWC, served as the paper’s editors and prominent contributors.

The NLL program prioritized evacuation of British troops and the independence of Palestine, calling for “a democratic government guaranteeing the rights of all inhabitants without distinction.” It differentiated between Zionism and the Jewish inhabitants of Palestine, and it criticized the other Arab parties — the largest were the Palestine Arab Party led by the Husayni family and the rival National Defense Party led by the Nashashibi family — for “ignoring the existence of the Jewish inhabitants” and refusing to grant them equal democratic rights as full citizens. While the NLL was an Arab national party, these positions bore the marks of its leaders’ communist training.

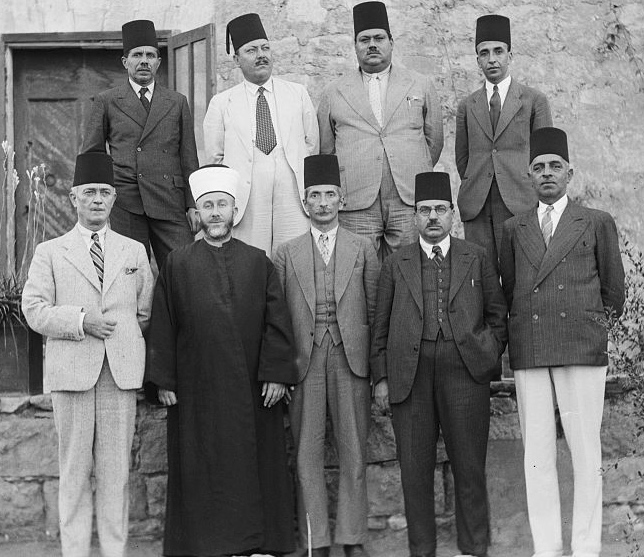

Members of the Arab Higher Committee. Front row from left to right: Raghib al-Nashashibi, Amin al-Husayni, Ahmed Hilmi Pasha, Abdul Latif Bey Es-Salah, and Alfred Roke, January 1, 1936. (Matson G. Eric and Edith Photograph collection/Library of Congress)

Meanwhile, in 1944, Shmuel Mikunis, Esther Vilenska, and Meir Vilner reestablished the PCP under their leadership, effectively as an all-Jewish party. As reported in “Kol ha-Am” (Voice of the Nation), the party’s Hebrew organ, in September 1945, the PCP’s Ninth Congress resolved that Palestine was a “country with a binational character” and called for establishing a “democratic and independent Arab-Jewish state.” This formulation signaled the first communist recognition of the yishuv as a national community, meaning Jewish settlers in Palestine had the right to self-determination, including the right to form a separate state, although the party continued to oppose this.

The question of partition

The principal difference between the PCP and the NLL, then, was their position on the question of whether or not settlers could acquire rights, and if so, what those rights would be.

The line of the re-established PCP did not recognize the national rights of a worldwide Jewish people or promote aliyah, so it was not fully Zionist. But it did seek to cooperate with Zionist parties that had a strongly pro-Soviet left wing, and with which it had programmatic agreement on labor and foreign policy issues. The popularity of the Soviet Union, due to its role in the defeat of Nazism and its legalization by the British, broadened the PCP’s opportunities for political action. Yet the party remained a minor player in the politics of the yishuv.

The NLL distinguished between the Zionist movement, which it opposed completely, and the population of the yishuv. The latter, it argued, deserved full and equal rights of citizenship, but not national rights, in an independent Palestine (recall that Arabs constituted two-thirds of the population in post-World War II British Mandate Palestine and Jews only one-third).

With the end of World War II, the demand for a Jewish state became far more acceptable to international opinion. Even among non-Zionists, establishing a Jewish state in Palestine was widely considered a form of reparations for the mass murder of European Jewry, an insurance policy against a recrudescence of fascist antisemitism, a foil to British imperialism in the Middle East, and a home for the roughly 225,000 Jews languishing in European displaced persons camps. Weighed against these considerations, Palestinian Arab national claims were considered less legitimate, and even politically dangerous because of Amin al-Husayni’s wartime collaboration with the Nazis.

Until the formation of the UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) in May 1947, the Soviet Union and the international communist camp upheld the line of Lenin and the Comintern: Zionism was an ally of imperialism; there was no worldwide Jewish nation; and British imperialism had imposed the yishuv as a settler colony on the indigenous Palestinian Arabs. But on May 14, 1947, Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko hinted at the Soviet Union’s willingness to abandon that position.

Jewish Jerusalemites celebrating the UN decision on the partition of Palestine, riding on top of an armored police car, Jerusalem, 1947, November 30, 1947. (Hans Pinn/GPO)

Addressing the UN General Assembly, he acknowledged the “exceptional sorrow and suffering” of the Jewish people during the war, and correctly argued that the Western European states failed “to ensure the defense of the elementary rights of the Jewish people and to safeguard it against the violence of the fascist executioners.” This, he said, “explains the aspirations of the Jews to establish their own state. It would be unjust not to take this into consideration and to deny the right of the Jewish people to realize this aspiration.”

Should a single state with equal rights for both peoples prove infeasible, Gromyko said, the Soviet Union would consider partitioning Palestine into an Arab and a Jewish state. And indeed, on October 3, 1947, it announced its support for the UNSCOP majority proposal recommending partition with an international corpus separatum in the Jerusalem-Bethlehem area.

This shift prompted the PCP to abruptly reverse course and rename itself the Communist Party of the Land of Israel (ha-Miflagah ha-Komunistit ha-Eretz Yisra’elit), adopting for the first time the Hebrew name for the country. The rival NLL initially rejected partition and asserted its right to maintain a position independent of the Soviet Union. But after the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 181 favoring the partition of Palestine on November 29, 1947, a slim majority of the NLL Central Committee accepted the UN resolution. Opponents of partition, led by Emile Tuma, were expelled from the party; Tuma was permitted to rejoin Maki only in 1951.

Reunification and reorientation

The reunification of Jewish and Arab communists under the Maki banner in October 1948, just months after the State of Israel was declared, was made possible by a political reassessment recognizing the rights of both the Arab and Jewish communities in Palestine-Israel to national self-determination, and consequently the legitimacy of partition.

The NLL signaled its ideological acquiescence to this line by signing on to a statement of the Iraqi, Syrian, and Lebanese communist parties that formally endorsed the partition of Palestine, in line with the policy of the USSR. These parties reasoned that the 1948 war was instigated by imperialism and reactionary Arab leaders. By extension, Arab resistance to the creation of Israel was illegitimate, and communist diplomacy to secure arms for Israel as well as service in the IDF were considered heroic. These dubious assertions consolidated a Jewish national tilt in Maki and fortified its claims to be a legitimate Israeli political party.

The decision of members of the NLL who remained inside Israel’s borders to join Maki was taken in the middle of a war during which Zionist forces were dismantling Palestinian Arab society, especially its urban and intellectual elements. The NLL and other progressive Palestinian forces were defeated, scattered, and persecuted. The Arab side, however one describes its configuration, had decisively lost the war by October 1948. Under those circumstances, NLL members concluded that becoming part of a legally recognized Israeli party was the best way to defend their people.

Members of the Communist Party on election day in Nazareth, January 25, 1949. (Hugo Mendelson/GPO)

In June 1951, acknowledging that the Palestinian Arab state envisioned in the 1947 Partition Plan was not being established, Fu’ad Nassar led NLL members who became refugees in the West Bank in forming the Communist Party of Jordan. The Jordanian party was illegal until 1993. Communists in the Gaza Strip regrouped as the Palestinian Communist Party of the Gaza Strip in 1953. Communism having been illegal in Egypt since the 1920s, the Egyptian authorities who ruled Gaza from 1948 to 1967 subjected its communists to constant harassment and a mass arrest campaign in 1959.

In October 1948, Maki held a “unity meeting,” which declared the “Restoration of a United Internationalist Communist Party in Each of the Two States.” In principle, the communists accepted the legitimacy of the State of Israel on the assumption that a Palestinian Arab state would also be established. In practice, that was unlikely to occur since the leaders in both Israel and its neighboring Arab states opposed such a state.

Shmuel Mikunis’s speech to the assembly sharply criticized the Israeli interim government’s expulsions of Palestinians, expropriations of their property, and opposition to establishing an independent Palestinian state, warning: “If matters continue in this way, then the war of liberation of the State of Israel may turn into an antidemocratic war of conquest.” As we now know, matters did continue in this way, but the communists were too weak to prevent it, while left-Zionists like Hashomer Hatzair rhetorically criticized the government’s ethnic cleansing policies even as their kibbutzim seized Palestinian lands.

Maki recognized the State of Israel within the borders of the UN Partition Plan. But gradually and reluctantly, the party participated in erasing Palestine from the map and the political horizon. Maki and its then overwhelmingly Jewish membership needed to adapt to the new Israeli political context, and therefore to reorient from a struggle against Zionism writ large to one for democracy, social justice, and equal rights for Palestinian Arab citizens, as well as the rights of Jewish and Arab workers within the parameters tolerated by the Israeli state.

Within these severe constraints, Maki was more thoroughly committed to equality and joint Arab-Jewish political action than any other Israeli political force. The party consistently opposed the military government imposed on Palestinian citizens of Israel from 1949 to 1966. Maki Knesset members Tawfiq Tubi and Meir Vilner battled heavy censorship to expose the Kufr Qasem massacre, which took place October 29, 1956. Furthermore, Maki was the only party to oppose the 1956 Suez War by Israel, France, and Britain as an imperialist war of aggression against Egypt.

These achievements established the basis for Maki’s future trajectory and primary political identity as the champion of the rights of the Palestinian citizens of Israel. Emphasizing its Arab program, however, ultimately undermined Maki’s aspirations to represent the entire Israeli working class — both Jewish and Palestinian.

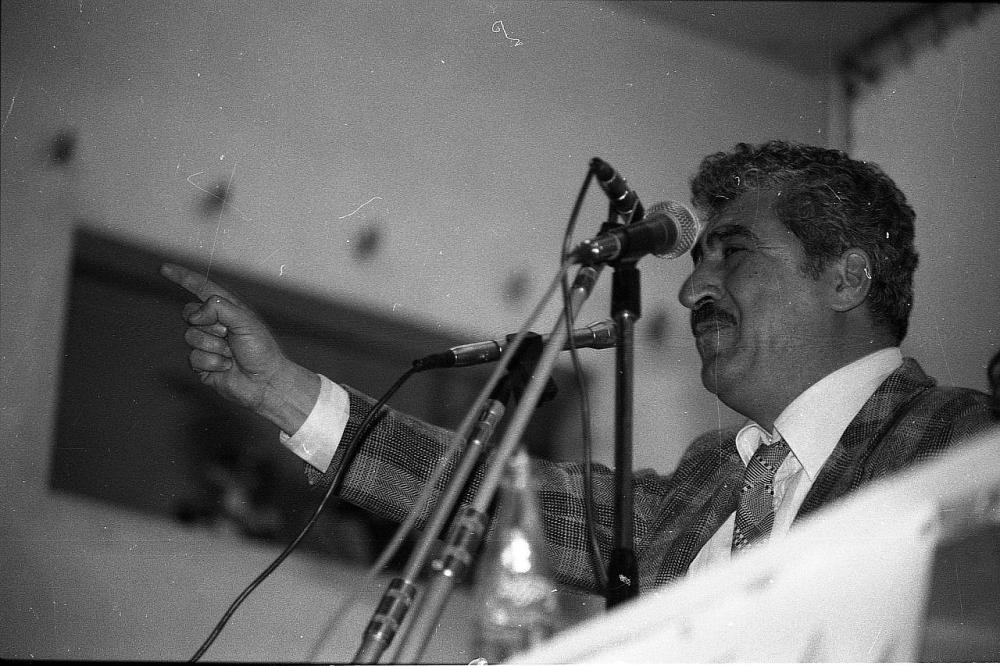

Tawfik Toubi, the Deputy-Secretary of the Hadash party, delivers a speech during a rally marking Land Day in the city of Sakhnin, March 30, 1988.

Meanwhile, the mass migration of Mizrahim (Jews who came from Muslim and/or Arab countries) to Israel lifted many veteran Ashkenazi workers familiar with the class-based discourse of communism out of the working class and into the middle classes. Nonetheless, Maki did win support among some Iraqi immigrants: literary luminaries such as Shimon Ballas, Sami Michael, David Semach, and Sasson Somekh, who had been members of or close to the Communist Party of Iraq, joined Maki after they arrived in Israel and wrote for Al-Ittihad.

Under pressure from Arab nationalism

In response to Nikita Khruschev’s denunciation of Stalin’s crimes in 1956, Palmiro Togliatti, the leader of Italy’s Communist Party, developed a theory of polycentrism and national roads to socialism. Jewish Maki leaders influenced by Togliatti began to imagine an Israeli road to socialism by drawing closer to Jewish national culture and seeking to ally with the left-Zionist MAPAM party, despite its support for the Suez War and its embrace of the Israeli national security consensus.

Nearly all of Maki’s Arab members resisted this approach, which would have diminished their standing in their own communities. Palestinians were also keenly aware that France, Israel’s co-conspirator in the Suez War and its principal ally and arms supplier from 1954 to 1967, was engaged in a cruel counterinsurgency war to thwart Algeria’s independence.

In 1947-49, the Soviet Union had determined that establishing a Jewish state was the strongest counter to British imperial ambitions in the Middle East. But after the 1956 war, the Arab nationalist movement — led by Egypt’s charismatic President Gamal Abdel Nasser — became the leading anti-imperialist force in the region, and consequently enjoyed increasing Soviet support. Maki’s standing in the Palestinian community in Israel was therefore under constant pressure from the mass appeal of Arab nationalism. Leaning toward Arab nationalism weakened the force of Maki’s Arab critics while any identification with Jewish national culture strengthened them.

These shifts naturally affected the party’s electoral success. Maki’s best result in its first 30 years was during the July 1955 election, when it won 4.5 percent of the total vote and six Knesset seats (at the time, the majority of the party’s voters were still Jews). In 1959, Nasser clashed with the Egyptian communists, who he subjected to mass incarceration and torture. Because of Nasser’s popularity among Palestinian citizens, Maki’s fortunes plummeted in the November 1959 election to 2.8 percent and three seats.

A militant campaign against the continuing efforts of Israeli authorities to expropriate Palestinian land restored the party’s popularity in the Arab community. The Israel Lands Authority, established in 1960, effectively prohibited Arab citizens from leasing 92 percent of all the land in the State of Israel. As part of the drive of the Israeli government to fortify its control, that same year Minister of Agriculture Moshe Dayan proposed an apartheid-style Consolidation of Lands Law. Maki led a successful mass struggle that defeated the draft legislation. In the August 1961 election, Maki won 4.2 percent of the total vote and five Knesset seats.

Israeli Communist Party MK Moshe Sneh addresses a crowd at an election campaign event in Ramat Gan, October 30, 1959. (Fritz Cohen/GPO)

This relative success temporarily moderated the party’s internal tensions over whether to adopt a Jewish or Arab national tilt. However, that outcome was almost entirely due to the doubling of the number of Maki’s Palestinian voters, most of whom were neither party members nor readers of Al-Ittihad.

Even as fellahin were becoming proletarianized, Arab support for Maki was most commonly due to its struggle for the rights of Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel, rather than identification with Marxism. At the same time, the party also built a base among aspiring Arab professionals by offering scholarships to promising students for university study in Moscow and other Soviet bloc capitals.

The final split

But those tensions could not be contained indefinitely. In 1965, the party split into two factions on largely ethnic lines: the all-Jewish Maki led by Shmuel Mikunis and Moshe Sneh, and the mostly Arab Rakah (New Communist List) led by Tawfiq Tubi and Meir Vilner. The Maki faction retained the party name after a court battle, but the Soviet Union recognized Rakah as the official communist party.

The June 1967 War and the ensuing occupation only broadened the gaps between the two factions. After the war, Maki collapsed into ineffectual left-Zionism. In 1975 it disappeared entirely. Meanwhile, by adopting the Soviet line on the war, Rakah lost nearly all support among Israeli Jews who were overwhelmingly in thrall to triumphalist nationalism.

The 1975 municipal election in Nazareth signaled Rakah’s surging power in the Arab community. The party, which had been strong in the city for two decades, won an absolute majority, and Tawfiq Ziad became the first communist mayor in Israel (and in the Middle East). Rakah built on this gain to initiate the National Committee to Defend the Land, which organized the Land Day general strike of March 30, 1976. Israeli forces killed six Arab demonstrators that day, which has since become a Palestinian national day of commemoration and protest.

Rakah’s prominent role in the Palestinian land struggle laid the foundation for the party to establish the Democratic Front for Peace and Equality (Hadash/al-Jabha) in 1976. This was a coalition of leftist groups, in which Rakah was the dominant force and maintained its autonomy. In some respects, the creation of Hadash reprised the strategy of the National Liberation League — to create a broad, left-leaning but not ideologically communist, patriotic front. The essential difference this time around was the presence of a Jewish component.

Tawfiq Ziad speaks during a meeting of the Communist Party in Nazareth, 1979. (Dan Hadani Collection/The Pritzker Family National Photography Collection/ The National Library of Israel/CC BY 4.0)

In the 1977 Knesset election, Hadash won a majority of the Arab vote and 4.6 percent of the total votes for the Knesset, better than any electoral result of pre-1965 united Maki. By putting Charlie Biton, a leader of the Israeli Black Panthers — which had led a militant struggle by Mizrahim for social equality in the early 1970s — high enough on its electoral list to win a Knesset seat, Hadash demonstrated its commitment to joint Jewish-Arab political action and more concern for the rights of Mizrahim than Maki ever had. These were major strategic achievements despite the fact that most Mizrahim continued to support parties of the right.

Hadash’s victory in the Palestinian community, which in Israel’s first decades voted mainly for parties of the Zionist left or their Arab satellite parties, opened the door for other independent Arab parties to compete for the Arab vote.

The Arab Democratic Party (al-Hizb al-Arabi al-Dimuqrati, known also by its Hebrew acronym Mada) was established in 1988 — when MK Muhammad Darawshe split from the Labor Party over then-Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s “break their arms and legs” tactics to suppress the First Intifada — and was the first legal all-Arab party in Israel. It was followed by the National Democratic Alliance (Al-Tajammu‘ al-‘Arabi al-Dimuqrati, or Balad), the Arab Movement for Renewal (Al-Haraka al-‘Arabiyya lil-Taghyir, or Ta‘al), and the United Arab List (Al-Qa’ima al-‘Arabiyya al-Muwahhada, or Ra‘am) in the mid-1990s.

Rakah reclaimed the Maki name in 1989, on the eve of the extinction of its historic lodestar, the Soviet Union. Since then, the party has struggled to overcome the legacy of its uncritical pro-Sovietism and the undemocratic elements in its political culture.

Old-new legacies

Perhaps the most significant legacy of its past is a tendency to understand the world in Cold War terms: an imperialist camp led by the United States, and an opposing camp that includes many authoritarian regimes. This led prominent Maki and Hadash leaders to make ambiguous and contradictory statements suggesting support for the Assad regime’s ruthless suppression of the 2011 popular uprising in Syria. A decade later, Maki refused to oppose Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and support the Ukrainian people’s right to self-determination.

Ahead of the 2015 election, the Israeli right succeeded in raising the electoral threshold to enter the Knesset in an attempt to wipe out the Arab parties. The Joint List was formed in response to this anti-democratic maneuver. In the 2015, September 2019, and 2020 elections, the Joint List was attractive enough to draw, at its peak, some 20,000 Jewish voters.

Members of the Joint List arrive for a meeting with Israeli President Reuven Rivlin at the President’s Residence in Jerusalem, as Rivlin begins consulting political leaders to decide who to task with trying to form a new government, September 22, 2019. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

But the fracturing of the Joint List in 2021 and 2022 disenchanted those who saw that as a cause for optimism. Since the November 2022 election, and in light of Ra‘am’s willingness to collaborate with right-wing parties and Balad’s failure to pass the threshold to enter the Knesset, Hadash-Ta’al has become the only reliable opposition to the Zionist consensus in the Knesset.

Why is all of this history relevant today? Because those who seek the decolonization of Israel/Palestine and the dismantling of Jewish supremacy between the river and the sea will only succeed if they convincingly uphold democratic and national rights for all. In this crucial political moment, then, Maki’s history can offer a potential starting point for rethinking the requisites of the kind of democratic Jewish-Arab unity that might counter the fascist wind coursing through the Israeli-Jewish body politic.

In addition to articulating a goal of decolonization and supporting a regime based on full civic equality and national rights for both Palestinian Arabs and Israeli Jews, such a formulation would also need to advocate enhancing the power and the rights of all working people between the river and the sea while understanding that class, ethnicity, and gender are mutually constitutive and inextricably intertwined. And like historic Maki, it would need to be rooted in the political realities of Palestine-Israel while maintaining solidarity with global progressive forces.

*Thanks to Zachary Lockman for comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Joel Beinin is the Donald J. McLachlan Professor of History and Professor of Middle East History, Emeritus at Stanford University. His research and writing focus on the social and cultural history and political economy of modern Egypt, Palestine, and Israel, and the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

Support journalism against apartheid. Become a member of +972 Magazine. We rely on YOUR contribution to expose and resist injustice in Israel-Palestine.