Hollywood Is a Union Town, but the History Is Complicated

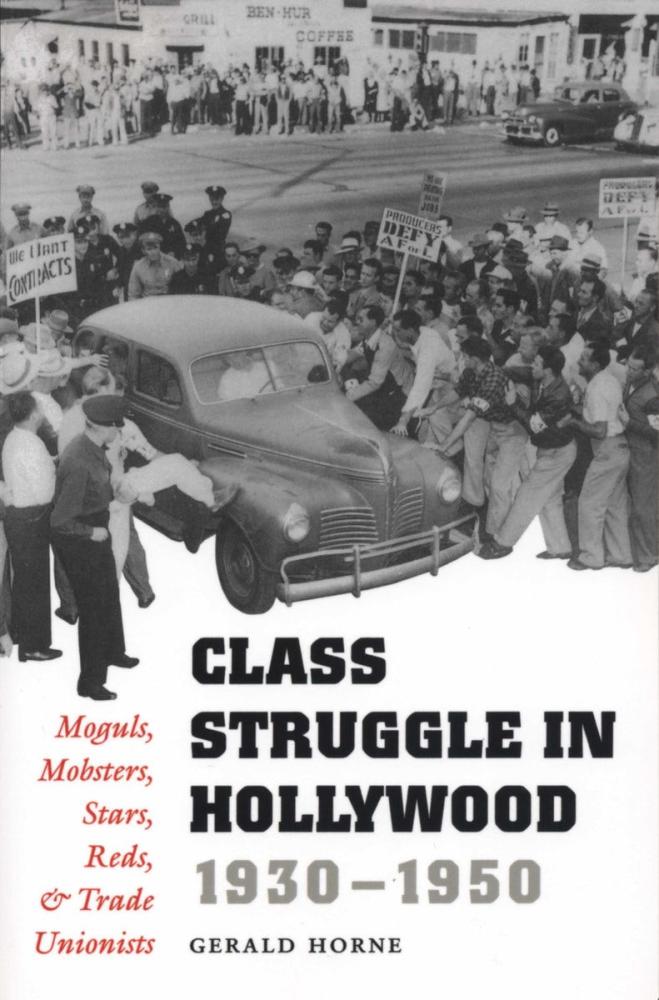

The American movie industry has been one of the most consistently unionized sectors of the economy since the 1930s — but to achieve that, workers had to overcome “the iron fist of the moguls” and organized crime, says historian Gerald Horne, author of Class Struggle in Hollywood 1930-1950.

Class Struggle in Hollywood, 1930-1950: Moguls, Mobsters, Stars, Reds, and Trade Unionists

by Gerald Horne

University of Texas Press; 468 pages

November 6, 2013

ISBN: 9780292750135

Craft workers — painters, plumbers, carpenters — were the first to organize, joining the International Association of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE), founded in New York in 1893. Five hundred of them went on strike in 1918. The Screen Writers Guild, ancestor of the Writers Guild of America, was founded at a meeting of 10 writers in February 1933, and the Screen Actors Guild, a few months later. (SAG merged with the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists to form SAG-AFTRA in 2012.) Teamsters Local 399, which now represents drivers, casting directors and more, emerged in the early 1930s.

Hollywood’s moguls and the Depression’s brutal economy gave workers a motive to organize: In March 1933, the main movie studios announced a 50% pay cut. The unions also benefited from a core of leftist militants, such as John Howard Lawson, the Screen Writers Guild’s first president and a Communist Party member who Horne calls “the spark.”

The Guild was elected bargaining agent for screenwriters in 1938, under the protections established by the new National Labor Relations Act. It did not win a full contract with the studios until 1941, though.

SAG’s impetus was money and safety. Their salaries had already been slashed in 1931, and Frankenstein star Boris Karloff complained about having to do a 25-hour shoot. By the end of the year, it had attracted stars like James Cagney and Groucho Marx, and membership reached 5,000 in 1935. It won its first contract in 1937. The American Federation of Radio Artists, AFTRA’s predecessor, formed that year and won its first contract in 1938.

IATSE already had a foothold in the film industry, with 9,000 members by 1933. But in 1934, it was taken over by organized crime, which installed George E. Browne as president. Browne and his partner, gangster Willie Bioff, worked out low-wage deals with the studio owners in exchange for bribes. They made several unsuccessful attempts to take over SAG, took a 2% kickback on paychecks and sent goons to break up a 1937 strike protesting such, and split up a local that rebelled against mob control.

The arrangement continued after Bioff and Browne were imprisoned on federal racketeering charges in 1941, with Roy Brewer heading the Hollywood locals.

A rival federation, the Conference of Studio Unions, attracted craft workers trying to get out from under that mob domination. Affiliated with the national Carpenters union, it also included painters and cartoonists and was headed by Herb Sorrell, a veteran of the failed 1937 strike.

The CSU’s numerous jurisdictional disputes with IATSE over who had the right to do which jobs came to a head in March 1945. Set decorators who had broken away from IATSE affiliated with CSU Local 1421. The studios refused to bargain with them, leading to a strike by more than 10,000 CSU members.

The strike slowed but didn’t halt film production. Thousands of IATSE members refused to cross the picket lines, according to Local 728’s website. But SAG members did, including a rising union official named Ronald Reagan.

Frustrated, CSU decided to try to stop production at the Warner Brothers lot in Burbank with mass picketing. On Oct. 5, several hundred picketers assembled outside the lot — they were assaulted by strikebreakers and mob goons on one side, and by Los Angeles County police with tear-gas bombs on the other.

The strike was settled later that month, but the studios blacklisted IATSE members who had refused to cross picket lines, and permanently locked out the CSU the next year.

By then, the mogul-mob alliance had a powerful new weapon against the unions: Anti-Communist hysteria was spreading rabidly across the country, and anyone with a leftist history was a target. Reagan, then beginning his devolution from a liberal to a far-right icon and soon to become SAG president, accused the CSU of being part of a “Soviet effort to gain control of Hollywood.” In reality, the Communist Party had opposed the 1945 strike.

In October 1947, the House Un-American Activities Committee held hearings on “Communist infiltration” of Hollywood, featuring “friendly witnesses” like Reagan and Ayn Rand. The committee vituperatively grilled the ten “unfriendly witnesses” about their political associations. Two of them, John Howard Lawson and Lester Cole, both among Writers’ Guild’s 10 founders, were imprisoned for contempt of Congress after they refused to answer questions. They and a third Guild cofounder, John Bright, were among the hundreds of people blacklisted from working in the industry until the 1960s.

The federal Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 required union officials to swear that they were not Communists, and most unions quickly went along. SAG in 1953 voted almost unanimously to impose a similar loyalty oath on new members.

Union density in Hollywood stayed near-universal, however. Most American employers in the 1950s didn’t have a problem with unions that had tamed themselves by purging the left. Density was around 90% in 1979, according to the Strikewave newsletter, but plummeted to less than half in the Reagan 1980s.

Meanwhile, the industry’s economics were upended in 1948 by the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Paramount Pictures Inc., which prohibited studios from owning movie theaters. That led to the end of the studio system, in which most workers were hired as employees under long-term contracts, and effectively made them freelancers. It coincided with the rise of television, making residuals — payments for reuse of their work, such as movies broadcast on TV or TV show reruns — an important source of income.

“Every industry-wide strike since 1950 has been about residuals,” Below the Stars author Kate Fortmueller wrote in the L.A. Review of Books in May.

The unions finally won residuals in 1960, after overlapping strikes by the Writers’ Guild and SAG. The Writers’ Guild has gone on strike eight times since 1950, including a four-month walkout in 1973 that won residuals for video sales and cable TV. SAG-AFTRA’s longest was an 11-month strike by video-game actors in 2016. The abysmal residuals for streaming are a main issue in the current strike.

Hollywood unions today, Horne says, “don’t have to face the tidal wave of red-baiting that they did in 1945 and 1946.” He hasn’t seen current SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher accused of being a closet Communist, he notes.

On the other hand, he adds, “they could use the kind of selflessness and energy that the Communists injected.”

[Steven Wishnia is an award-winning journalist and veteran editor. His writing has appeared in the Nation, the Progressive, the Village Voice, Alternet.org, and High Times, among other publications. As a musician, he may be best known as the '80s punk band False Prophets' bass player.]

The Indypendent is a New York City-based newspaper and website. Our independent, grassroots journalism is made possible by readers like you. Please consider making a recurring or one-time donation today or subscribe to our monthly print edition and get every copy sent straight to your home.