Hellen Keller’s Forgotten Radicalism

In December 2020, over 50 years after Helen Keller’s death, the renowned deafblind woman became ensnared in controversy, as she often had in life. “Helen Keller is not radical at all,” Black disability-rights activist Anita Cameron told Time magazine. “Just another, despite disabilities, privileged white person, and yet another example of history telling the story of privileged white Americans.” Ironically, right-wing figures from Ted Cruz to Donald Trump, Jr. jumped in to defend Keller — a lifelong avowed radical socialist — from “wokeism.” Around the same time, a viral TikTok video accused Keller of being a “fraud,” arguing that no deafblind person could have written books, graduated (with honors) from Radcliffe, flown an airplane or achieved many of her storied accomplishments.

As all this shows, Helen Keller has long been reduced to “inspiration porn,” a term coined by disability activist Stella Young to describe how disabled people are often objectified to uplift the nondisabled. Keller has been reduced to the cliché of the disabled overachiever, seemingly unimpeded and unbothered by her disabilities. Little of her life is remembered beyond the “miracle” moment in 1886 when her teacher Annie Sullivan got through to her inaccessible six-year-old self. Keller’s fascinating and complicated story has become largely hidden from history.

While previous conventional wisdom about Keller largely restricted her radicalism to the early 20th century, Wallace lays out evidence that she actually shifted even further left after World War I, identifying not just as a socialist, but as a Communist.

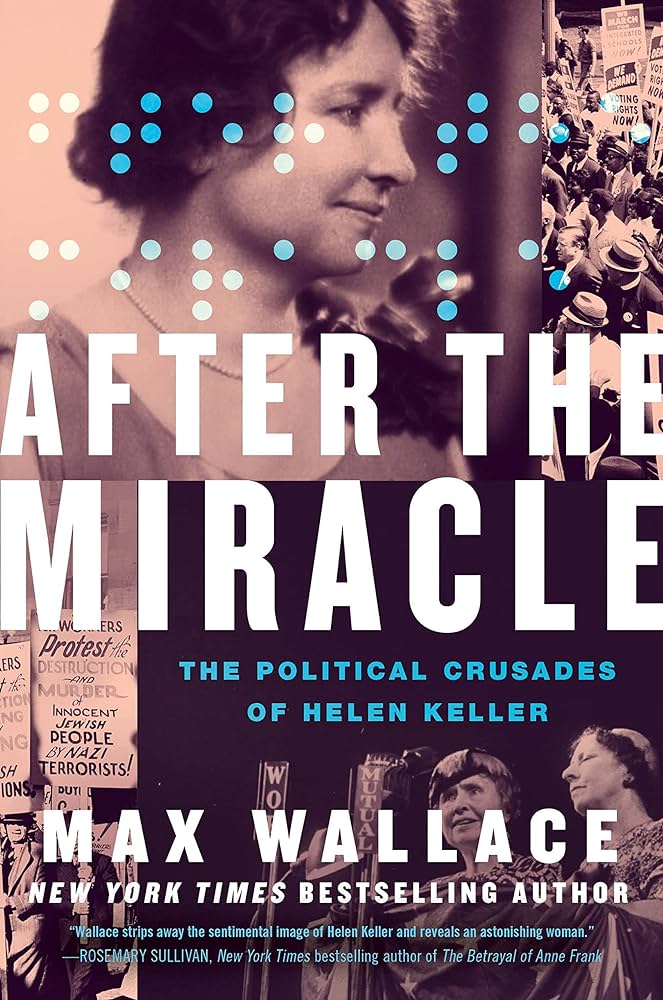

Fortunately, scholar and disability advocate Max Wallace restores Keller’s legacy as an empowered, independent thinker and activist in his new biography, After the Miracle: The Political Crusades of Helen Keller. The book refreshingly reestablishes Keller’s agency. All the ink spilled over the last century about Keller — biographies, historical novels, plays, movies, articles and the like — enables Wallace to circumvent the typical chronological narrative and just stick to his focus: reinscribing Keller’s radicalism.

While many credit Keller’s socialist awakening to Sullivan’s husband John Macy, Wallace provides evidence that she identified as a socialist well before he did, and in fact likely brought him over to the cause. Indeed, Macy is nowhere to be found in Keller’s 1912 essay “How I Became a Socialist,” written three years after she joined the party; in it, she largely cites reading as opening her mind to the cruelty of capitalism, particularly poverty’s connection to disability.

A huge public figure in the early 20th century, Keller was also hugely public about her politics. She staunchly opposed America entering the first world war, publicly supported the Russian revolution, joined the International Workers of the World (IWW) and fiercely supported women’s right to vote. “I believe suffrage will lead to socialism,” she told The New York Times, “and to me socialism is the ideal cause.” Wallace smartly notes that Keller made public remarks far worse than many of those arrested, imprisoned and/or deported under the 1918 Sedition Act, yet remained untouched.

Curiously, the ableism Keller endured could also protect her, as many people simply assumed that she had been tricked or manipulated into her beliefs. She caused a stir when in 1916 she sent a check for $100 (about $3,000 today) to the NAACP, accompanied by a passionate letter decrying racism as “a denial of Christ.” This was a far cry from her roots growing up in postbellum Alabama as the daughter of a Confederate soldier and granddaughter of slave owners. Keller’s letter was published in the NAACP newsletter The Crisis, then reprinted in Alabama’s Selma Journal — alongside a broadside that insisted Keller’s impressionable mind must have been “poisoned” by her Northern teachers. Again, Keller’s perceived lack of agency provided a dubious security; for, as Wallace argues, she very well could have been lynched for her beliefs.

While previous conventional wisdom about Keller largely restricted her radicalism to the early 20th century, Wallace lays out evidence that she actually shifted even further left after World War I, identifying not just as a socialist, but as a Communist. She praised Lenin and the Russian Revolution in her 1929 memoir Midstream; that same year, she told a reporter that she was “a socialist and a Bolshevik”.

Indeed, by World War II, Wallace says there’s “absolutely no doubt that Helen had become a Fellow Traveler” with the Communist Party, embracing the party without formally becoming a member. He cites Keller’s positions on the war, which closely mirrored the party’s: despite being so anti-fascist as to support the Spanish loyalists in the Spanish Civil War, Keller opposed U.S. entry into World War II until Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, at which point she did an abrupt about-face. Her fat FBI file documented her friendships with known and suspected Communists, from John Reed, to Howard Fast, to Dorothy Parker (not to mention that joyful anarchist firecracker Emma Goldman). In 1952 Keller publicly endorsed a Stalinist gathering, the Congress of the Peoples for Peace, cabling, “Am with you in your splendid movement.”

But Keller wasn’t merely a reflexive party follower. Wallace highlights her keen international perspective. She visited South Africa and decried its system of apartheid over 30 years before the issue became a worldwide concern; while there, she befriended Gandhi’s family and praised his campaign against British colonialism. She read and wrote in five different languages (in Braille!), subscribed to numerous international newspapers, and closely followed world events.

What’s more, Wallace reinscribes not just Keller’s radicalism, but also her spirited personality. He portrays her quick wit; even comedian Harpo Marx, another friend, told a reporter he had trouble keeping up with her dry humor. And while history has written off Keller as a spinster, Wallace explores her little-known affair with fellow socialist Peter Fagan. The two applied for a marriage license and planned to elope; but Fagan stood her up, and broke her heart. Wallace even indulges in the far-fetched speculation that Keller and her longtime teacher Sullivan may have been lovers; though it’s doubtful that they were romantically involved, they were certainly family to each other.

After the Miracle: The Political Crusades of Helen Keller By Max Wallace Grand Central Publishing, 2023; 416 pages

Above all, Wallace reminds us, Keller thought for herself. Though she never quite conceived of disability as marking an oppressed class in itself, she was ahead of her time in seeing how it is so often linked to race, gender and class oppression. She saw how capitalism could cause or exacerbate disabilities, ironically a situation which has in many ways worsened with time. Keller was cognizant of the relationship between poverty and disability — and indeed, acutely aware of her privilege. Her legendary can-do attitude came not from being “inspirational,” but from a complex understanding of her situation that included the knowledge of just how comparatively lucky she actually was. And she wanted to share the wealth — or, more accurately, redistribute it. Keller died in 1968 at age 87, remaining, in one friend’s words, “true to her socialist principles to the end.”

Jessica Max Stein (“Max”) has been a New York-based writer since the early 90s. She teaches writing and literature at the City University of New York (CUNY), and received her M.F.A. in creative writing from Brooklyn College.

Stein is writing Funny Boy: The Richard Hunt Biography, the life story of Muppet performer Richard Hunt. Biographers International Organization honored the Funny Boy book proposal as one of three finalists for its 2016 Hazel Rowley Prize.

Stein’s writing has been cited in the New York Times, received an Amy Award for young writers from Poets and Writers magazine, and won an Ippie for Best Editorial from the Independent Press Association. A reporter and former editor of the Indypendent, Stein has published work in over 100 magazines and journals, including a longtime column at The Bilerico Project.

See Stein’s Patreon page to support the book and read exclusive excerpts!

Contact the author at richard.hunt.biography at gmail dot com.

The Indypendent is a New York City-based newspaper and website. Our independent, grassroots journalism is made possible by readers like you. Please consider making a recurring or one-time donation today or subscribe to our monthly print edition and get every copy sent straight to your home.