Workers Funding Other Workers’ Misery

Critics of private equity often stress the business model’s impact on workers. Blackstone’s Packers Sanitation Services, Inc., was found to have illegally hired over 100 minors and placed them in dangerous jobs. Arby’s and Dunkin’ Donuts owner Roark Capital lobbied against a federal minimum wage. Fairmont and Sofitel owner Brookfield Asset Management has repeatedly threatened to retaliate against hotel workers attempting to unionize. And when the private equity purchase of Toys ‘R’ Us drove the toy retailer into bankruptcy, leading to a loss of over 30,000 jobs, its owners Bain Capital, KKR, and Vornado Realty Trust made off with about $200 million in management fees.

“They’re making money even when they’re hurting the underlying business,” said Bianca Agustin, the co-executive director of retail workers advocacy group United for Respect, which found that over 1.3 million workers lost their jobs due to private equity and hedge fund ownership.

But when private equity firms need the financing to continue inflicting this damage on workers, they turn, confoundingly, to other workers.

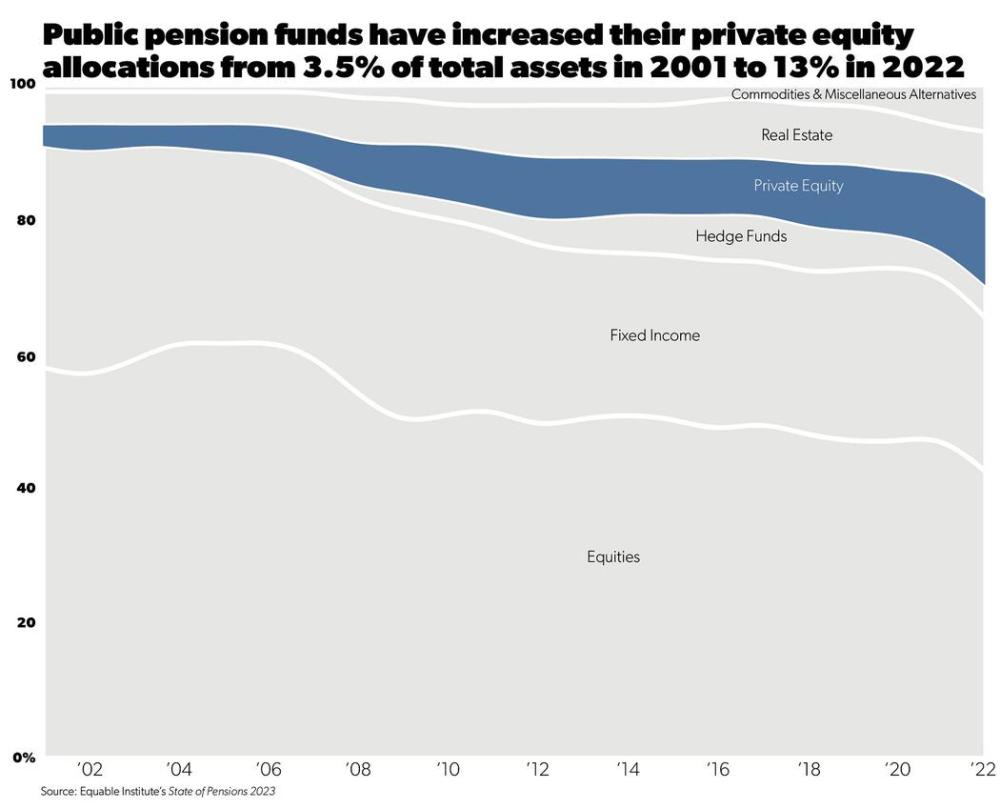

Public pension funds are now the largest backers of private equity, based on a database of 6,700 buyouts between 1997 and 2018 collected by recently graduated Columbia Business School Ph.D. student Vrinda Mittal. Pension funds, which are almost one-third of all investors in private equity, have invested 13 percent of their capital in the asset class—over $620 billion in 2022—up from 3.5 percent in 2001 and 8.3 percent in 2011, according to data from public pension research nonprofit Equable Institute. Pension funds like CalPERS, the second-largest in the U.S. with $462 billion in assets, said they are planning to allocate more money to private equity.

“Private equity is fundamentally dependent upon public pension funds. gives them a lot more power,” said David H. Webber, a Boston University law professor who writes about shareholder activism.

Public pension funds have been unmoved by an array of studies showing that private equity buyouts have led to job losses, wage cuts, lower revenue, labor productivity decline, and company bankruptcies. There are even examples of public employee savings being used to cut the wages of their own members. In 2011, Aramark, then private equity–owned and backed by 37 state and local retirement funds, underbid a custodians’ union for school cleaning contracts, and then offered the custodians their jobs back at $11 less per hour.

“If you’re killing jobs, even if you get a good return, you could be hurting the fund because now you don’t have people paying into it,” Webber said.

The growing clout with private equity offers pension funds the power to condition their financing on better labor practices. They can tell fund managers “the way you handle this [labor issue] is important to us if we’re gonna invest with you again in the future,” said Justin Flores, labor-jobs director at the Private Equity Stakeholder Project.

But pension funds contacted by the Prospect were reluctant to even discuss their private equity holdings, much less commit to using them in a way beneficial to their fellow workers.

A Repeated Pattern

At a New Jersey plant run by Refresco, which produces drinks like Arizona Iced Tea and Tropicana juices, safety violations ensued after the company was bought by private equity giant KKR last February.

Ivan Rios, who has worked at the Refresco job site for 20 years—having joined when it was Whitlock Packaging—said working conditions at the plant did not get better after KKR took over, though KKR pledged to allow space for “worker voice” and improve workplace safety. In January, a worker fell off a tanker truck ladder, while a June case involving two workers who suffered steam burn injuries is still under investigation, an OSHA spokesperson confirmed. In April, another worker fell and broke his leg. OSHA told Refresco to investigate the incident, letters between the agency and Refresco’s lawyer showed. KKR and Refresco did not respond to a request for comment.

Eight of the 16 investors in KKR Global Infrastructure Investors IV, the KKR fund that owns Refresco, are public pension funds, with investments of at least $1.28 billion. The New York City pension system, the fifth-largest in the country, is invested in the KKR fund, along with employee pension funds for New York state and Hawaii, and the Alaska Permanent Fund, data from Infrastructure Investor showed.

It’s becoming more common for private equity to sell a portfolio company to itself, making it harder to reveal its true value.

This pattern is repeated over and over. Blackstone Core Equity Partners, the fund that purchased child labor employer PSSI, includes backers like the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), New York State Common Retirement Fund, North Carolina Department of State Treasurer, and Houston Firefighters’ Relief and Retirement Fund. Roark Capital, the fast-food chain owner that lobbied against the minimum-wage increase, has 11 different pension funds invested in its fund Roark Capital Partners V, data from private equity research firm Preqin showed. Backers of the funds that bought Toys ‘R’ Us include public employees in California, teachers in Texas, and the Oregon State Treasury.

BC Partners bought PetSmart in March 2015, and workers have subsequently endured rampant understaffing, which has led to psychological torment. The BC European Capital IX fund that bought PetSmart has 140 backers, Preqin data showed. A whopping 24 of them are American public pension funds, including CalSTRS and the NYC Employees’ Retirement System. The total U.S. public pension investment is at least $1.37 billion; some funds did not disclose how much they invested in the fund. (For data that was recorded in euros, the USD conversion rate on August 18, 2023, was used.)

Blackstone and PSSI said in separate statements that they are against child labor violations and have taken “extensive” steps to prevent it from happening again. BC Partners and Roark Capital did not respond to requests for comment.

After controlling for post-buyout acquisitions and divestitures, employment shrank by 4.4 percent at firms bought out by private equity, Harvard University and University of Chicago economists who studied 6,000 buyouts between 1980 and 2013 found. Mittal’s study found that at private equity–owned firms, five years after a buyout, employment fell nearly 24 percent, revenue dropped about 23 percent, and labor productivity dipped 0.4 percent.

One-fifth of private equity buyouts lead to bankruptcies within ten years of going private, California State Polytechnic University researchers who studied 484 leveraged buyouts between 1980 and 2006 found.

Reluctant Pushback

John Ocampo, a field organizer with the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE), said that New York City’s pension system “somewhat” helped Refresco workers, who were negotiating for a first union contract this year (they got it in July). The workers met with staff at City Comptroller Brad Lander’s office, which oversees the city’s pension funds, including the one that owns Refresco.

The Comptroller’s Office asked KKR to meet with the workers and said they were concerned about the factory’s safety issues. The office said it “wasn’t their place” to intervene in contract negotiations, Ocampo said. “It’s hard to say how much of an impact that had but it likely did serve to help the company understand that it was in its best interests to reach an agreement.”

John Adler, the Comptroller’s chief ESG officer, cited a similar action encouraging BC Partners to talk to PetSmart employees. “We facilitated dialogue between the company and its workers. And we think that’s a positive thing,” he said.

New York City retirement systems have occasionally refused to commit to several private equity firms’ funds, including Carlyle Partners after 2013 and Trilantic North America after 2019. But that’s an infrequent tactic.

Adler said the system cannot make an investment decision on “one factor” alone. “[We look] at all risk factors, including investment risks, reputational risks, long-term climate risks … and labor risk,” he said, adding that as limited partners, the system cannot micromanage every action the private equity fund makes.

Even New York City’s circumspect use of pension fund leverage was rare among private equity investors. The Prospect reached out to 26 public pension funds, and 22 either declined or did not respond to requests to explain why they invest in private equity, and whether they have addressed the labor consequences of their investments.

Those that did respond, including the State Board of Administration of Florida and the Arizona State Retirement System, cited their “focus” on their fiduciary responsibility to maximize returns. “As private equity investors we focus solely on pecuniary factors and have no involvement in the operations or labor practices of any of these companies,” Florida’s spokesperson wrote in an email. Florida committed about $100 million in BC European Capital IX—the fund that owns PetSmart—but said they sold their interest in that particular fund “years ago.”

CalSTRS, which at $314 billion is the country’s third-largest pension fund, and which committed about $258 million to the BC Partners fund and $500 million to PSSI owner Blackstone Core Equity Partners, declined an interview request and pointed to its ESG investment policy. One of the risk factors includes “worker rights,” where the investment noted “the right to organize and bargain collectively,” “status of child labor practices and minimum age for employment,” and other labor rights.

Questionable Returns

Public pension funds first moved into more volatile assets in the 1970s, chasing a target annualized return of 8 to 9 percent. But following the stock market crash of the 2008 financial crisis, allocations to alternative investment funds like private equity increased.

Diversification helps pension funds reduce the risk of a particular asset class driving down the whole portfolio. But fund trustees also buy into private equity’s marketing pitch. “If you are a trustee … and your choices are between going to the legislature and saying we need more money,” said Anthony Randazzo, Equable Institute’s executive director, “or from listening to this private equity manager who just came in to pitch you on, ‘Hey, our fund’s going to … beat the S&P,’ you’re probably gonna go [private equity’s] way.”

Indeed, public pension funds justified their holdings by claiming that private equity improves returns. Arizona’s system argued that the returns “enable us to drive down the contributions that need to be paid by our employees and employers,” it said in a statement. Maryland’s pension fund also attributed their fund’s improving performance to private equity.

Yet studies have shown that private equity doesn’t outperform public markets. One University of Oxford study of over 2,100 private equity funds between 2006 and 2015 found that these funds provided the same returns as public equity indices, net of fees, for which investors were charged $230 billion.

Jeffrey Hooke, a former private equity and investment executive who now teaches at Johns Hopkins University’s Carey Business School, explained how private equity “can make up their own results.” Private equity firms come up with what they think their unsold portfolio companies are worth, plumping up their funds’ financial performance on paper. No one knows their real value until they are sold. Even Goldman Sachs said funds tend to mark up existing assets. And it’s becoming more common for private equity to sell a portfolio company to itself, making it harder to reveal its true value.

Pension fund executives buy the hype to keep their jobs, Hooke said. Investing in funds that track the stock and bond markets requires few people—Nevada’s pension fund famously did it. And pension fund staffers listen to pension fund consultants and private equity players because that’s where they want to end up next in their careers.

Meanwhile, pension boards, often made up of retirees and union representatives, don’t have the investment expertise, so they put their trust in the consultants, Hooke said.

Labor’s Time in the Sun

Public pension funds have wielded power before, taking stances against apartheid in South Africa, tobacco, terrorism, guns, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and fossil fuels. The value of private prison companies GEO Group and CoreCivic fell extensively after public pension funds divested from the two largest publicly traded operators.

Some funds say they are working to extend this to labor issues. “Figuring out a systematic way to ensure workers’ rights across our portfolio is a priority of ours,” said Alison Hirsh, the NYC Comptroller’s Office chief strategy officer.

Given that half of New York City’s pension fund boards of trustees, who vote on investment decisions, are workers and union representatives, private equity funds need to present acceptable labor standards to win them over, she added. “We can have a material impact on companies’ workers rights practices through engagement.”

Like New York City’s pension system, several pension funds have responsible contractor policies, although these mostly apply only when the pension fund has a minimum 50 percent stake in the investment, which doesn’t apply to private equity holdings.

When Toys ‘R’ Us’s severance pay promise was rescinded, Minnesota’s state pension withheld investments in KKR temporarily. KKR and Bain Capital later set up a $20 million hardship fund (though not the $75 million workers felt they were owed).

Labor advocates argue that a greater investor focus on private equity labor practices would benefit returns and the wider economy. “Labor disputes cost money,” Flores said. “In a bunch of industries where there are strikes happening, companies are unable to fill positions, unable to grow because they can’t staff.”

Making sure the private equity funds’ portfolio companies aren’t cutting employees or going bankrupt will “do the economy a net positive if you can stave off hundreds and thousands of layoffs that will strain the unemployment rolls,” Agustin said.

Recently, there’s been pushback against pension funds wielding their might on social issues, particularly around so-called environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices. Three New York pension funds were sued by members for cutting their stakes in fossil fuels.

But with private equity, public pension funds have grown vital enough that they could simply decline to invest in firms with poor labor practices, without necessarily taking a hit to their own returns. But that would require pension fund managers to connect the workers they represent with the workers who are being harmed by their investments.

Note: Rachel Phua is now a journalist for Bloomberg based in Singapore. This story was submitted and edited before she joined Bloomberg.

This article appears in the October 2023 issue of The American Prospect magazine. Subscribe here.