After 112 Years, Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Victims Get a Memorial

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911 was one of the most notorious fires in New York City history, trapping workers, primarily young immigrant women, who had endured poor conditions on the job in a burning building they could not escape. In all, 146 workers died in the blaze.

The fire helped galvanize a budding U.S. labor movement, but for decades, the only memorial to its victims in the Greenwich Village neighborhood where the factory once stood was a bronze plaque. Until now.

On Wednesday, a striking memorial was unveiled at the building that once housed the factory, at an event that drew descendants of the victims and a range of public officials, including the acting labor secretary of the United States and the governor of New York.

Gov. Kathy Hochul said that New York was “the birthplace of the workers’ rights movement because of what happened right on this block. That is something we tout to the rest of the world.”

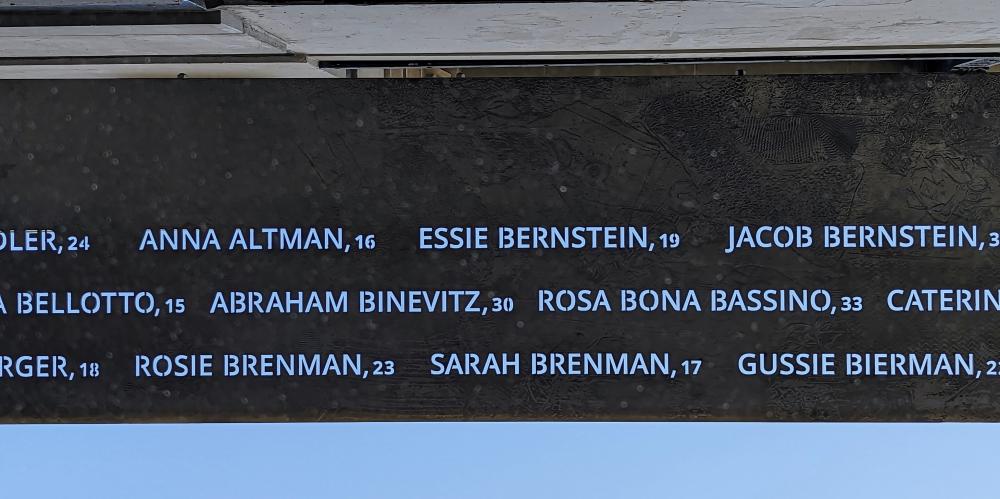

The memorial — which features horizontal stainless-steel plates on two sides of the building bearing the victims’ names and ages and a reflective panel with survivor and eyewitness testimony — was the result of more than a decade of work from the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition, a group made up of labor advocates and victims’ relatives.

“It is gratifying for all the family members of those who died in this tragic fire to know that through the memorial, this and future generations will learn about the fire and its significance in labor history,” Suzanne Pred Bass said during the dedication ceremony, which drew a crowd of hundreds. Two of her great-aunts worked at the factory, and one of them, Rosie Weiner, died in the fire.

The building where the factory once stood is now owned by New York University and is used mainly for its biology and chemistry laboratories.

A second phase of the memorial, which will be completed this winter, will feature a stainless steel ribbon reaching up to the ninth floor of the building, from which more than 50 of the workers jumped to their deaths.

The fire broke out on the eighth floor on March 25, 1911. There were no overhead sprinklers in the factory, and the flames spread rapidly. The factory did not conduct fire drills, and its managers were slow to notify workers of the fire; they had also locked a door to one of the staircases, preventing many of the workers from escaping.

Though the factory’s employees worked on the eighth, ninth and tenth floors of the building, the Fire Department’s ladders reached only as high as the sixth. Workers filed onto a poorly constructed fire escape that collapsed.

Most of the victims were young immigrant women from Eastern Europe and Italy who worked as many as 84 hours a week for as little as $7.

“We can imagine the black plume of smoke up in the air, the flames that spread from floor to floor, the panic of the workers who ran and found closed exits and broken fire escapes,” Julie Su, the acting labor secretary, said Wednesday. “Their cries for help and then the thud of bodies as they began to jump one after another.”

Ms. Su noted that one of the people who had “looked on in horror” as the building burned was Frances Perkins, who happened to be nearby and who went on to become the first woman to serve as labor secretary.

After the fire, New York began requiring automatic sprinklers in tall buildings and fire drills in large workplaces.

Several speakers alluded to the worker protections the fire helped usher in, including safe working conditions, fair wages and the right to organize.

“Tragically, many of these protections are being eroded by unscrupulous employers as greed continues to endanger workers,” Lynne Fox, the president of Workers United, said.

Speakers mentioned the SAG-AFTRA and United Automobile Workers members who are currently on strike, and those working to unionize at Starbucks, Amazon, Trader Joe’s and elsewhere.

“So many of the changes that have happened in this great city have happened as a result of tragedy, and that is not the way that it should happen,” said Rebecca Damon, executive director for labor policy for SAG-AFTRA’s New York local.

“But when it does happen, New Yorkers say, ‘No, we will not accept this and we will give dignity to workers,’” Ms. Damon said.

The Triangle Shirtwaist memorial was designed by Richard Joon Yoo and Uri Wegman, who won a design competition in 2013. New York State offered $1.5 million for the memorial, and labor unions and foundations also offered financial support.

Erica Lansner, 65, who attended the ceremony with her cousins, said that it was “a great honor” to see their great-aunt Fannie Lansner’s name etched on the memorial and to know that she was not only a victim but also “part of a legacy of change in labor history and fire regulations.”

Her great-aunt, an immigrant from Lithuania, helped bring other women to safety before the elevator stopped working, Ms. Lansner said. She jumped to her own death once it became clear that she could not escape.

Rob del Castillo, 57, was there on Wednesday to honor his great-aunt Josie, who had come from Sicily and was just 20 years old when she died in the fire.

“It is incredibly poignant and compelling,” he said of the memorial. “It’s also a reminder that although we’ve come a long way as far as workers’ rights, in some respects we still have a long way to go.”

Elizabeth Yuan contributed reporting.

Lola Fadulu is a general assignment reporter on the Metro desk of The Times. She was part of a team that was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize in 2023 for coverage of New York City’s deadliest fire in decades. More about Lola Fadulu

The New York Times offers a range of subscription types that provide digital access.

All Access subscriptions bring you every one of The Times’s digital products all together, including News, plus Games, Cooking, Wirecutter and The Athletic. If you prefer, you can subscribe to any of these products individually. To purchase an All Access subscription, visit nytimes.com/subscription.