Anatomy of a North Carolina Gerrymander

When states redrew congressional maps after the 2020 census, North Carolina was one of the nation’s big success stories. That’s not because lawmakers drew fair maps — they drew what would have been one of the most extreme gerrymanders in the country. Rather, North Carolina was a success because a majority of the North Carolina Supreme Court, relying on state law, ruled that drawing maps to entrench the party in charge violated the state constitution.

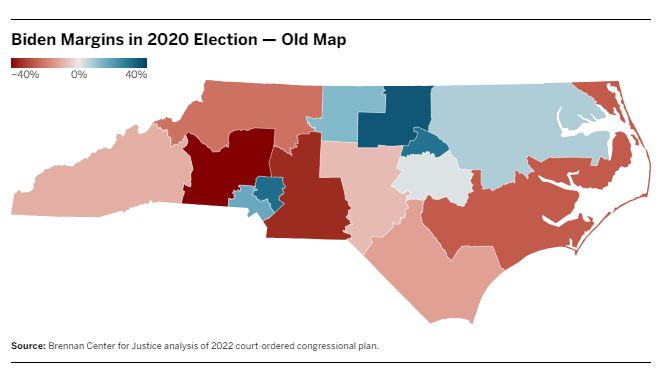

The result of the ruling was adoption of a court-drawn map that was one of the fairest the Tar Heel State has seen in decades, with Democrats and Republicans each winning seven seats in the 2022 midterms — a result in line with North Carolina’s status as one of the country’s most hotly contested electoral battlegrounds.

But that win for voters has proven short lived.

After Republican candidates won two seats on the North Carolina Supreme Court in the 2022 midterms, giving the court a conservative majority, Republican lawmakers wasted no time in asking the court to reverse earlier rulings that partisan gerrymandering violated the state constitution.

The court’s new majority obliged, handing down a controversial opinion in late spring that abruptly abandoned any role for state courts in policing gerrymandering, declaring that gerrymandering claims were non-justiciable “political questions” off limits to the judiciary.

With overtly partisan line drawing no longer illegal, Republicans began preparing to undo the balance that had been established in the maps. The question wasn’t whether the maps would get worse — it was by how much.

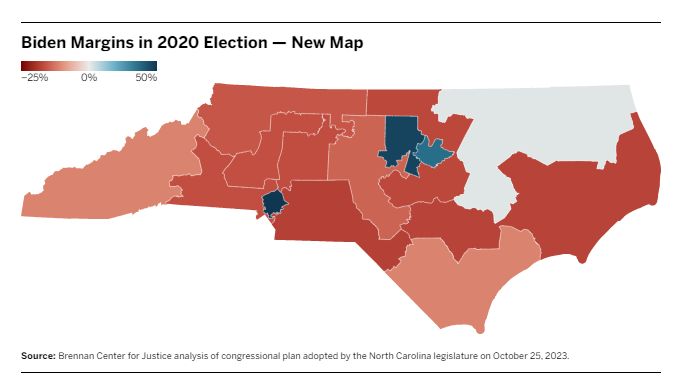

The answer came this week: much worse. Under the new congressional map rushed through the legislature on a party-line vote, a balanced, 50–50 map that reflected North Carolina’s purple state politics was transformed into one that could elect as many as 11 Republicans and just 3 Democrats. (North Carolina’s governor does not have the power to veto election maps.)

By Brennan Center calculations, the new map easily ranks, along with Texas’s, as one of the two most extreme congressional maps currently in place. Indeed, the Republicans’ new North Carolina gerrymander is so durable that even an exceptionally strong Democratic wave year (think 2018) would not dislodge it. Even under the rosiest of foreseeable scenarios, Democrats win at most 4 of 14 seats. Put another way, Democrats could win a solid majority of the ballots cast for Congress, but their candidates would win less than 30 percent of seats thanks to Republicans’ carefully engineered gerrymander.

The Republican gerrymander has three components.

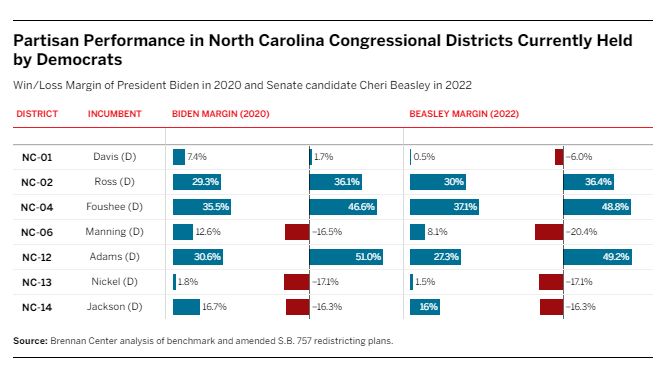

First, three compact, comfortably Democratic seats in the Piedmont Triad (NC-06), metro Charlotte (NC-14), and metro Raleigh (NC-13) are dismantled and converted into solidly Republican districts that spill across multiple regions of the state.

Next, three urban Democratic districts — two in the Raleigh-Durham region (NC-02 and NC-04) and one in metro Charlotte (NC-12) — are made even more Democratic through the packing of additional Democratic-leaning voters into them. Under the redrawn map, Joe Biden in 2020 and Democratic Senate candidate Cheri Beasley in 2022 not only win the districts but do so by overwhelming margins — in some cases by nearly 50 percentage points.

Finally, in eastern North Carolina, the heavily rural but Democratic-leaning First District is transformed through swapping of counties into a Republican-trending tossup district that Beasley lost by six points in 2022 race and that Biden barely carried in 2020.

The fallout from the new map has been swift. Democrat Rep. Jeff Jackson, who currently represents the 14th District, quickly announced that he would forgo a run for reelection in a radically redrawn district that former President Trump would have carried by more than 16 points in 2020, but instead would seek election as North Carolina’s attorney general.

And not surprisingly, in a state where politics and race are often joined at the hip, many of the voters most impacted by a map that discriminates against Democrats are voters of color.

In particular, Rep. Don Davis, a Black Democrat who represents the First District, could face increasingly difficult electoral prospects as the decade goes on if the rural portions of his district continue the steady drift of recent years toward Republicans. And should Davis retire, a non-incumbent Black Democrat would likely find the district even harder to hold given the region’s pronounced racially polarized voting and the lack of any incumbency advantage. In either case, the redrawn map could mean the end of a performing district where Black voters have successfully elected a Black Democrat since the 1990s.

The new map also divides Black communities in the Piedmont Triad (as the cities of Greensboro, Winston-Salem, and High Point are known) between three different districts, all of which sprawl across different regions of the state and all of which are very solidly Republican. Under the old map, they had been kept together in the Sixth District, a Piedmont Triad-centered district where a diverse, multiracial coalition elected Democrat Kathy Manning to Congress.

Voters of color in Charlotte, likewise, are packed into the overwhelmingly Democratic 12th District, which becomes more than 60 percent non-white, while neighboring 14th District sees its non-white voting age population fall from nearly 40 percent to under 30 percent, helping to transform the district into a strongly Republican seat.

Voters and advocates will almost certainly challenge the new map in court. And recent wins in Alabama and just this week in Georgia show that it is still possible to win relief under federal law from discriminatory maps.

But advocates also will enter the fight over North Carolina’s new maps having to rely on a legal toolbox that has become decidedly threadbare. In 2013, the Supreme Court gutted key protections of the Voting Rights Act, and in 2019, it ruled that federal courts could not hear partisan gerrymandering claims. Congress has yet to step in to provide a remedy.

Congress had the opportunity in 2021 to pass the Freedom to Vote Act and John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, two bills that together would have banned partisan gerrymandering by statute and strengthened the Voting Rights Act. They passed the House only to die in the Senate due to the failure of enough senators to agree to changes to archaic filibuster rules.

If recent wins against gerrymandering in state courts around the country provided a feeling that perhaps nothing more was needed from Congress, North Carolina is a warning. In the fight against gerrymandering and racially discriminatory maps, it is not enough to rely exclusively on state courts. State courts and state constitutions are important tools for protecting democratic rights, but, as North Carolina illustrates, they can be subject to fickleness of state politics. To make sure Americans have protections against discriminatory line drawing, Congress also must act.