Traveling for Abortions: The Untold Story

This week, Kate Cox got an abortion. She joined more than 9.3 million Americans who got a legal abortion in the past 10 years, of which 83,000 (0.9%) got one after 20 weeks of gestation.

I’ve seen many on social media wonder: What’s the big deal? She found the healthcare she needed after all, right? And this cross-state journey is rare, right?

Forced abortion travel has doubled following Dobbs. And if you’re one of the lucky few who can travel, this journey isn’t without very real challenges that may not be apparent to the unseen eye.

The journey

The journey for an abortion looks very different depending on who you are. In general, though, many challenges could be prevented if we, as a society, accepted abortion as healthcare.

First, many people’s journeys stop before they begin:

-

It takes a lot of cash—plane tickets, rental car, hotel rooms, food, and procedure. This adds up to about $10,000-$30,000. As you can imagine, many people can’t afford this, and often, insurance doesn’t cover it.

-

Half of all abortion seekers live below the Federal Poverty Level—an income of less than $13k/year.

-

This is especially true for adolescents and teens (who make up a big number of later abortion patients), undocumented people, and parents.

-

If they make the journey, it’s not without other hard realities:

-

Pain meds are available. For those later in pregnancy, though, it doesn’t do much. You may not have access to an epidural, depending on the state’s regulations, because you’re at an outpatient clinic. This is unimaginable pain—in all senses of the word.

-

Your partner can’t be there to support you during labor, like hold your hand, or coach you through pain. You can’t have a phone, either. Tight security is required at abortion clinics. In the same vein, you walk past protesters yelling at you every morning and every night for a week. You wish, with all your heart, you could enjoy the same level of ignorance.

-

Recovering in a hotel room means a cold, unfamiliar place. Without your slippers, without your bed, without your cat, and without access to the comfort food you crave. All you want to be is at home.

-

The journey means needing time off from work and getting your FMLA form signed by a physician in another state. All you hope is that your employer won’t ask questions because you don’t have any energy to explain.

-

The journey may include carrying the baby’s ashes on an airplane. This requires holding back a flood of emotions in public—exhaustion, grief, anxiety, pain, a strong desire for privacy.

-

People who have abortions are no more likely to struggle with mental health than the people who do not—in fact, not getting a needed abortion has been found to increase anxiety and depression in the first 12 months. But there are emotional costs in needing to travel, and much of that is driven by stigma and ostracization of abortion care. Also, recognizing when you need help (remember you don’t have a follow-up appointment with your OB) and finding the right clinician or therapist, given the unique circumstances and the trust required, is hard.

Two things help:

-

The confidence in making the right decision: 95% of people who have an abortion say it was the right decision for them. The most common emotion reported afterward is relief.

-

The healthcare workers—literally angels on earth—at the abortion clinic ensure moments of human connection, empathy, and support. You feel cared for, which helps tremendously. And the rare souls you trust with your story like family, friends, and clinicians thereafter also help tremendously.

Travel for abortions is increasing

This journey is becoming more common. Before Dobbs, 1 in 10 women having abortions had to travel. Now it’s double— 1 in 5. We see increased travel from many angles:

-

While the number of abortions across states has greatly shifted post-Dobbs, the national average hasn’t budged.

-

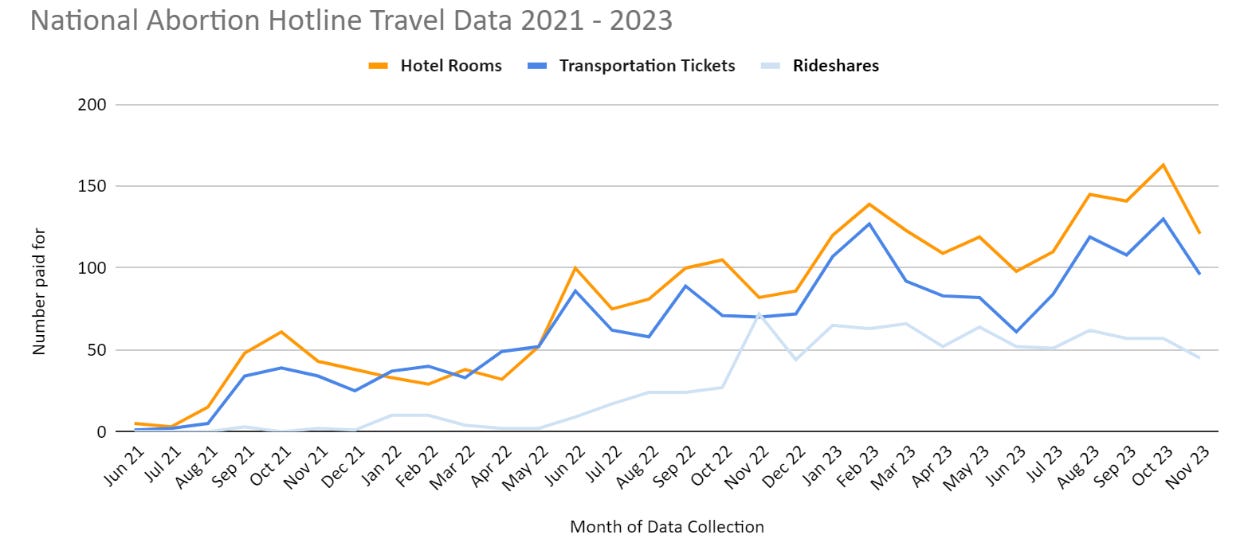

Calls to the National Abortion Hotline for travel services, like hotel rooms and plane tickets, have tripled post-Dobbs and remain high.

National Abortion Federation. Source here.

-

Scientists who measured distance to abortion facilities found travel time increased, on average, by three times post- Dobbs. In Texas, for example, the new travel time to the nearest abortion facility increased by almost a full workday.

This speaks to why we see increases in self-managed abortion (i.e., medication abortion). It’s also why colleagues in Latin America, for example, have been supporting people to self-manage with pills up to 24 weeks of pregnancy, which is safe and effective.

Bottom line

An increasing number of women are traveling out of state for reproductive healthcare. This journey isn’t without very real obstacles. The most tragic part is much of the associated trauma is preventable if we just had access to local healthcare.

It may be hard to understand, but it’s harder for people to live through. Trust women. Listen to their stories. Trust their voices. It is, after all, their lives and their livelihoods.

Love, YLE

If you want to support travel for abortions, here are some great options.

-

The Brigid Alliance supports people who are traveling for abortions at 15+ weeks.

-

National Network of Abortion Funds a collective of over 100 abortion funds across the United States.

-

Jane’s Due Process funds abortion and practical support for Texas teens traveling for abortion care

A big thank you to Dr. Heidi Moseson — a reproductive epidemiologist— who helped immensely with much of the piece’s research.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe to Your Local Epidemiologist.