CNN Staff Say Network’s Pro-Israel Slant Amounts to ‘Journalistic Malpractice’

CNN is facing a backlash from its own staff over editorial policies they say have led to a regurgitation of Israeli propaganda and the censoring of Palestinians perspectives in the network’s coverage of the war in Gaza.

Journalists in CNN newsrooms in the US and overseas say broadcasts have been skewed by management edicts and a story-approval process that has resulted in highly partial coverage of the Hamas massacre on 7 October and Israel’s retaliatory attack on Gaza.

“The majority of news since the war began, regardless of how accurate the initial reporting, has been skewed by a systemic and institutional bias within the network toward Israel,” said one CNN staffer. “Ultimately, CNN’s coverage of the Israel-Gaza war amounts to journalistic malpractice.”

According to accounts from six CNN staffers in multiple newsrooms, and more than a dozen internal memos and emails obtained by the Guardian, daily news decisions are shaped by a flow of directives from the CNN headquarters in Atlanta that have set strict guidelines on coverage.

They include tight restrictions on quoting Hamas and reporting other Palestinian perspectives while Israel government statements are taken at face value. In addition, every story on the conflict must be cleared by the Jerusalem bureau before broadcast or publication.

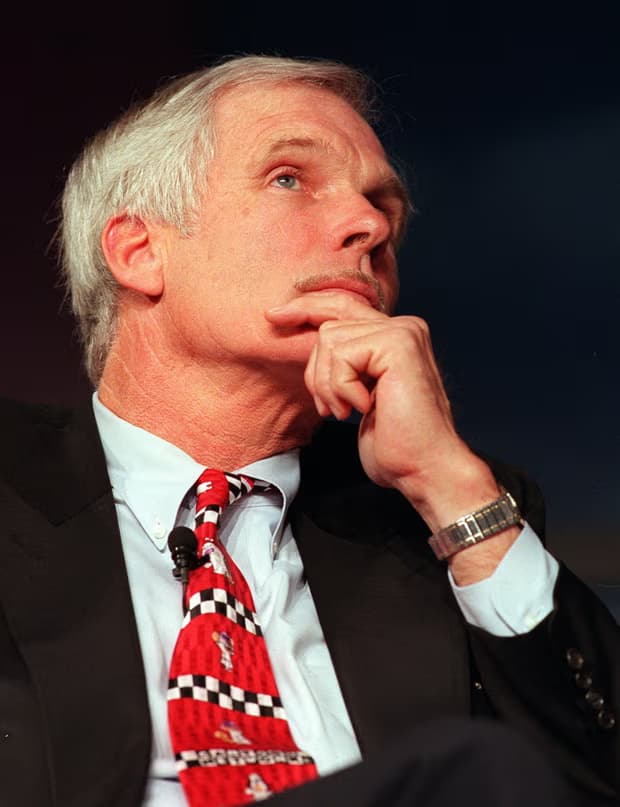

CNN journalists say the tone of coverage is set at the top by its new editor in chief and CEO, Mark Thompson, who took up his post two days after the 7 October Hamas attack. Some staff are concerned about Thompson’s willingness to withstand external attempts to influence coverage given that in a former role as the BBC’s director general he was accused of bowing to Israeli government pressure on a number of occasions, including a demand to remove one of the corporation’s most prominent correspondents from her post in Jerusalem in 2005.

Mark Thompson. Photograph: Kirsty Wigglesworth/AP

CNN insiders say that has resulted, particularly in the early weeks of the war, in a greater focus on Israeli suffering and the Israeli narrative of the war as a hunt for Hamas and its tunnels, and an insufficient focus on the scale of Palestinian civilian deaths and destruction in Gaza.

One journalist described a “schism” within the network over coverage they said was at times reminiscent of the cheerleading that followed 9/11.

“There’s a lot of internal strife and dissent. Some people are looking to get out,” they said.

Another journalist in a different bureau said that they too saw pushback.

“Senior staffers who disagree with the status quo are butting heads with the executives giving orders, questioning how we can effectively tell the story with such restrictive directives in place,” they said.

“Many have been pushing for more content from Gaza to be alerted and aired. By the time these reports go through Jerusalem and make it to TV or the homepage, critical changes – from the introduction of imprecise language to an ignorance of crucial stories – ensure that nearly every report, no matter how damning, relieves Israel of wrongdoing.”

CNN staff say that some journalists with experience of reporting the conflict and region have avoided assignments in Israel because they do not believe they will be free to tell the whole story. Others speculate that they are being kept away by senior editors.

“It is clear that some who don’t belong are covering the war and some who do belong aren’t,” said one insider.

Edicts from on high

At Thompson’s first editorial meeting, two days after the 7 October Hamas attack, the new network chief described CNN’s coverage of the rapidly moving story as “basically great”.

Thompson then said he wanted viewers to understand what Hamas is, what it stands for and what it was trying to achieve with the attack. Some of those listening thought that a laudable journalistic goal. But they said that in time it became clear he had more specific expectations for how journalists should cover the group.

In late October, as the Palestinian death toll rose sharply from Israeli bombing with more than 2,700 children killed according to the Gaza health ministry, and as Israel prepared for its ground invasion, a set of guidelines landed in CNN staff inboxes.

Palestinians mourn their loved ones in Deir Al-Balah, Gaza, on 31 October 2023. Photograph: Ashraf Amra/Anadolu via Getty Images

A note at the top of the two-page memo pointed to an instruction “from Mark” to pay attention to a particular paragraph under “coverage guidance”. The paragraph said that, while CNN would report the human consequences of the Israeli assault and the historical context of the story, “we must continue always to remind our audiences of the immediate cause of this current conflict, namely the Hamas attack and mass murder and kidnap of civilians”. (Italics in the original.)

CNN staff members said the memo solidified a framework for stories in which the Hamas massacre was used to implicitly justify Israeli actions, and that other context or history was often unwelcome or marginalised.

“How else are editors going to read that other than as an instruction that no matter what the Israelis do, Hamas is ultimately to blame? Every action by Israel – dropping massive bombs that wipe out entire streets, its obliteration of whole families – the coverage ends up massaged to create a ‘they had it coming’ narrative,” said one staffer.

The same memo said that any reference to casualty figures from the Gaza health ministry must say it is “Hamas-controlled”, implying that reports of the deaths of thousands of children were unreliable even though the World Health Organization and other international bodies have said they are largely accurate. CNN staff said that edict was laid down by Thompson at an earlier editorial meeting.

Broader oversight of coverage from the CNN headquarters in Atlanta is directed by “the Triad” of three CNN departments – news standards and practices, legal, and fact checking.

CNN’s headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, in 2019. Photograph: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images

David Lindsay, the senior director of news standards and practices, issued a directive in early November effectively barring the reporting of most Hamas statements, characterising them as “inflammatory rhetoric and propaganda”.

“Most of it has been said many times before and is not newsworthy. We should be careful not to give it a platform,” he wrote.

Lindsay said that if a statement was deemed editorially relevant “we can use it if it’s accompanied by greater context, preferably a package or digital write. Let’s avoid running it as a standalone soundbite or quote.”

In contrast, one CNN staffer noted that the network repeatedly aired inflammatory rhetoric and propaganda from Israeli officials and American supporters, often without challenge in interviews.

They noted that other channels have carried interviews with Hamas leaders while CNN has not, including one in which the group’s spokesman, Ghazi Hamad, cut short questions from the BBC when he was challenged about the murder of Israeli civilians. One staffer said there is a view among correspondents that it is “agony to get a Hamas interview past the Triad”.

Hamas chief Ismail Haniyeh in Qatar, Doha, 20 Dec 2023 Photograph: Iranian Foreign Ministry/ZUMA Press Wire/REX/Shutterstock

CNN sources acknowledged there have been no interviews with Hamas since the 7 October attack, but said the network does not have a ban on such interviews.

But CNN news desks and reporters have been instructed not to use video recorded by Hamas “under any circumstances unless cleared by the Triad and senior editorial leadership”.

That position was reiterated in another instruction on 23 October that reports must not show Hamas recordings of the release of two Israeli hostages, Nurit Cooper and Yocheved Lifshitz. Two days later, Lindsay sent an additional instruction that video of the 85-year-old Lifshitz shaking hands with one of her captors “can only to be used when specifically writing about her decision to shake hands with her captor”.

Yocheved Lifshitz, who was held hostage in Gaza after Hamas’s 7 October attack, speaks in Tel Aviv on 24 October 2023, a day after being released. Photograph: Ariel Schalit/AP

In addition to the edicts from Atlanta, CNN has a longstanding policy that all copy on the Israel-Palestine situation must be approved for broadcast or publication by the Jerusalem bureau. In July, the network created a process it called “SecondEyes” to speed up those approvals.

The Jerusalem bureau chief, Richard Greene, told staff in a memo announcing SecondEyes – first reported by the Intercept – that, because coverage of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is subject to close scrutiny by partisans on both sides, the measure was created as a “safety net so we don’t use imprecise language or words that may sound impartial but can have coded meanings here”.

CNN staffers said there is nothing inherently wrong with the requirement given the huge sensitivity of covering Israel and Palestine, and the aggressive nature of Israeli authorities and well-organised pro-Israel groups in seeking to influence coverage. But some feel that a measure that was originally intended to maintain standards has become a tool of self-censorship to avoid controversy.

One result of SecondEyes is that Israeli official statements are often quickly cleared and make it on air on the principle that that they are to be trusted at face value, seemingly rubber-stamped for broadcast, while statements and claims from Palestinians, and not just Hamas, are delayed or never reported.

One CNN staffer said edits by SecondEyes often seemed aimed at avoiding criticism from pro-Israel groups. They gave the example of Greene’s intervention to change a headline, “Israel is nowhere near destroying Hamas” – a perspective widely reflected in the foreign and Israeli press. It was replaced with headline that shifted the focus from whether Israel could achieve its stated justification for killing thousands of Palestinian civilians: “Three months on, Israel is entering a new phase of the war. Is it still trying to ‘destroy’ Hamas?”

Some CNN staff fear that the result is a network acting as a surrogate censor on behalf of the Israeli government.

“The system results in chosen individuals editing any and all reporting with an institutionalised pro-Israel bias, often using passive language to absolve the [Israel Defense Forces] of responsibility, and playing down Palestinian deaths and Israeli attacks,” said one of the network’s journalists.

CNN staff who spoke to the Guardian were quick to praise thorough and hard-hitting reporting by correspondents on the ground. They said those reports are often given prominence on CNN International, seen outside the US. But on the CNN channel available in the US, they are frequently less visible and at times marginalised by hours of interviews with Israeli officials and supporters of the war in Gaza who were given free rein to make their case, often unchallenged and sometimes with presenters making supportive statements. Meanwhile, Palestinian voices and views were far less frequently heard and more rigorously challenged.

One staffer pointed to the appearance of Rami Igra, a former senior official in the Israeli intelligence service, on Anderson Cooper’s show, where he claimed that the entire Palestinian population of Gaza could be regarded as combatants.

Anderson Cooper before the start of a Republican presidential debate in Des Moines, Iowa, on 10 January. Photograph: Andrew Harnik/AP

“The non-combatant population in the Gaza Strip is really a nonexistent term because all of the Gazans voted for the Hamas and as we have seen on the 7th of October, most of the population in the Gaza Strip are Hamas,” he said.

“Nonetheless, we are treating them as non-combatants, we are treating them as regular civilians, and they are spared from the fighting.”

Cooper did not challenge him on either point. By the time the interview aired on 19 November, more than 13,000 people had been killed in Gaza, most of them civilians.

Another CNN staffer picked out anchor Jake Tapper’s programme as an example of an anchor too closely identifying with one side while the other gets only a restricted look in. In one segment, Tapper acknowledged the death and suffering of innocent Palestinians in Gaza but appeared to defend the scale of the Israeli attack on Gaza.

“What exactly did Hamas think the Israeli military would do in response to that?” he said, referring to the attack on 7 October.

A CNN spokesperson said: “We absolutely reject the notion that any of our journalists treat Israeli officials differently to other officials.”

Another presenter, Sara Sidner, drew criticism for her excitable report on unverified Israeli claims that Hamas beheaded dozens of babies on 7 October.

“We have some really disturbing new information out of Israel,” she announced four days after the attack.

Sara Sidner in New York on 10 December 2023. Photograph: Evan Agostini/Invision/AP

“The Israeli prime minister’s spokesman just confirmed, babies and toddlers were found with their heads decapitated in Kfar Aza in southern Israel after Hamas attacks in the kibbutz over the weekend. That has been confirmed by the prime minister’s office.”

Sidner called the claim “beyond devastating”.

“For the families listening, for the people of Israel, for anyone that is a parent, who loves children, I don’t know how they get through this,” she said.

Sidner then put it to a CNN reporter in Jerusalem, Hadas Gold, that the decapitation of babies would make it impossible for Israel to make peace with Hamas.

Gold replied: “How can you when you’re dealing with people who would do such atrocities to children, to babies, to toddlers?”

Gold, who was part of the SecondEyes team approving stories, again said the report was confirmed by Netanyahu’s office and she drew parallels with the Holocaust. She responded to a Hamas denial that it had decapitated babies as unbelievable “when we literally have video of these guys, of these militants, of these terrorists doing exactly what they say they’re not doing to civilians and to children”.

Except, as a CNN journalist pointed out, the network did not have such video and, apparently, neither did anyone else.

Hadas Gold in Lisbon, Portugal, in 2019. Photograph: Eóin Noonan/Sportsfile for Web Summit/Getty Images

“The problem was that yet again the Israeli government’s version of events was promoted in an emotional way with very little scrutiny by someone who is supposed to be a neutral news presenter,” they said.

By the time of Sidner’s broadcast there were already good reasons for CNN to treat the claims with caution.

Israeli journalists who toured Kfar Aza the day before said they had seen no evidence of such a crime and military officials there had made no mention of it. Instead, Tim Langmaid, the Atlanta-based CNN vice-president and senior editorial director, sent an instruction that President Biden’s claims to have seen pictures of the alleged atrocity “back up what the Israeli government said”.

Even as the questions grew, Langmaid sent out a memo saying: “It is important to cover the atrocities of the Hamas attacks and war as we learn them.”

CNN insiders said senior editors should have treated the story with caution from the beginning because the Israeli military has a track record of false or exaggerated claims that subsequently fall apart.

Other networks, such as Sky News, were considerably more sceptical in their reporting and laid out the tenuous origins of the story which began with a reporter for an Israeli news channel who said soldiers told her that 40 children were killed in the Hamas massacre and that one soldier said he had seen “bodies of babies with their heads cut off”. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) then used the claim to liken Hamas to the Islamic State.

Damaged houses are marked off with tape in the Kfar Aza kibbutz, Israel, on 14 January. Photograph: Amir Cohen/Reuters

Even after the White House admitted that neither the president nor his officials had themselves seen pictures of beheaded babies, and that they had been relying on Israeli claims, Langmaid told the newsroom it could still report the Israeli government assertions alongside a denial from Hamas.

CNN did report on the rolling back of the claims as Israeli officials backtracked, but one staffer said that by then the damage had been done, describing the coverage as a failure of journalism.

“The infamous ‘beheaded babies’ claim, attributed to the Israeli government, made it to air for roughly 18 hours – even after the White House walked back on Biden’s statement that he had seen the nonexistent photos. CNN had no access to photographic evidence, nor any ability to independently verify these claims,” they said.

A CNN spokesperson said the network accurately reported what was being said at the time.

“We took great care to attribute these claims across our reporting, and we also issued very specific guidance to this effect,” they said.

Some CNN staff raised similar issues with reporting on Hamas tunnels in Gaza and claims they led to a sprawling command centre under al-Shifa hospital.

Insiders say some journalists have pushed back against the restrictions. One pointed to Jomana Karadsheh, a London-based correspondent with a long history of reporting from the Middle East.

“Jomana has really pushed to shine a spotlight on the Palestinian victims of this war and she has had some success. She’s done some really important stories putting a human face on it all and in looking at Israeli actions and intent. But I don’t think it’s been easy for her. These stories don’t get the prominence they deserve,” one said.

CNN producer Jomana Karadsheh in Tripoli, Libya, on 24 August 2011. Photograph: Paul Hackett/Reuters

The push for more balanced coverage has been complicated by Israel’s block on foreign journalists entering Gaza except under IDF control and subject to censorship. That has helped keep the full impact of the war on Palestinians off of CNN and other channels while ensuring that there is a continued focus on the Israeli perspective.

A CNN spokesperson rejected allegations of bias.

“Our reporting has confronted Israel’s response to the attacks, including some of our most detailed and high-profile investigations, interviews and reports,” they said.

CNN faced similar accusations of partiality in the wake of the 9/11 attacks in 2001 when the network’s chair, Walter Isaacson, ordered that reports on the killing of Afghan civilians by US forces be balanced with condemnation of the Taliban for its links to al-Qaida.

“As we get good reports from Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, we must redouble our efforts to make sure we do not seem to be simply reporting from their vantage or perspective. We must talk about how the Taliban are using civilian shields and how the Taliban have harbored the terrorists responsible for killing close to 5,000 innocent people,” he wrote in a memo, according to the Washington Post.

Some staffers say that after the first few weeks in which CNN reported the Hamas attack “like it was 9/11”, more space was made for the Palestinian perspective given the escalating death toll and destruction from Israel’s retaliatory attack on Gaza.

The only foreign journalist to report from Gaza without an Israeli escort has been CNN’s Clarissa Ward, who entered for two hours with a humanitarian team from the United Arab Emirates.

Ward acknowledged the challenges in the Washington Post last week. She wrote that her reporting from Israel allowed her “to create a vivid picture of the monstrosities of Oct 7” but she was being prevented from conveying a fuller picture of the tragedy unfolding in Gaza because of the Israeli block on foreign journalists, putting the burden solely on a limited number of courageous Palestinian reporters who are being killed in disproportionate numbers.

“We must now be able to report on the horrific death and destruction being meted out in Gaza in the same way – on the ground, independently – amid one of the most intense bombardments in the history of modern warfare,” she wrote.

“The response to our report on Gaza in Israeli media suggests an unspoken reason for denying access. When asked on air about our piece, one reporter from the Israeli Channel 13 replied, ‘If indeed Western reporters begin to enter Gaza, this will for sure be a big headache for Israel and Israeli hasbara.’ Hasbara is a Hebrew word for pro-Israel advocacy.”

Clarissa Ward, CNN’s chief international correspondent, at an event in New York on 19 September 2023. Photograph: John Lamparski/Getty Images for Concordia Summit

Some at CNN fear that its coverage of the latest Gaza war is damaging a reputation built up by its reporting of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which led to a surge in viewers. But others say that the Ukraine war may be part of the problem because editorial standards grew lax as the network and many of its journalists identified clearly with one side – Ukraine – particularly at the beginning of the conflict.

One CNN staffer said that Ukraine coverage set a dangerous precedent that has come back to haunt the network because the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is far more divisive and views are much more deeply entrenched.

“The complacency in our editorial standards and journalistic integrity while reporting on Ukraine has come back to haunt us. Only this time, the stakes are higher and the consequences much more severe. Journalistic complacency is an easier pill for the world to swallow when it’s Arab lives lost instead of European,” they said.

Another CNN employee said the double standards are glaring.

“It’s OK for us to be embedded with the IDF, producing reports censored by the army, but we cannot talk to the organisation that won a majority of the votes in Gaza whether we like it or not. CNN viewers are being prevented from hearing from a central player in this story,” they said.

“It is not journalism to say we won’t talk to someone because we don’t like what they do. CNN has talked to plenty of terrorists and America’s enemies over the years. We’ve interviewed Muammar Gaddafi. We’ve even interviewed Osama bin Laden. So what’s different this time?”

Years of pressure

Journalists working at CNN have varied explanations.

Some say the problem is rooted in years of pressure from the Israeli government and allied groups in the US combined with a fear of losing advertising.

During the battle for narrative through the second Palestinian intifada in the early 2000s, Israel’s then communications minister, Reuven Rivlin, called CNN ‘‘evil, biased and unbalanced”. The Jerusalem Post likened the network’s correspondent in the city, Sheila MacVicar, to “the woman who refilled the toilet paper in the Goebbels’ commode”.

Then Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon, right, talks with Maj Gen Yoav Gallant, center, and Reuven Rivlin, left, in Jerusalem on 14 October 2004. Photograph: Muhammed Muheisen/AP

CNN’s founder, Ted Turner, caused a storm when he told the Guardian in 2002 that Israel was engaging in terrorism against the Palestinians.

“The Palestinians are fighting with human suicide bombers, that’s all they have. The Israelis … they’ve got one of the most powerful military machines in the world. The Palestinians have nothing. So who are the terrorists? I would make a case that both sides are involved in terrorism,” said Turner, who was then the vice-chairman of AOL Time Warner, which owned CNN.

The resulting storm of protest resulted in threats to the network’s revenue, including moves by Israeli cable television companies to supplant the network with Fox News.

Ted Turner in Anaheim, California, in 1995. Photograph: Kevork Djansezian/Associated Press

CNN’s chair, Walter Isaacson, appeared on Israeli television to denounce Turner but that did not stem the criticism. The network’s then chief news executive, Eason Jordan, imposed a new rule that CNN would no longer show statements by suicide bombers or interview their relatives, and flew to Israel to quell the political storm.

CNN also began broadcasting a series about the victims of Palestinian suicide bombers. The network insisted that the move was not a response to pressure but some of its journalists were sceptical. CNN did not produce a similar series with the relatives of innocent Palestinians killed by Israel in bombings.

By 2021, the Columbia Journalism Review public editor for CNN, Ariana Pekary, accused the network of excluding Palestinian voices and historical context from coverage.

Thompson has his own battle scars from dealing with Israeli officials when he was director general of the BBC two decades ago.

In the spring of 2005, the BBC was embroiled in a very public row over an interview with the Israeli nuclear whistleblower Mordechai Vanunu, who was released from prison the year before.

Mordechai Vanunu leaves Shikmain prison in Ashkelon, Israel, on 21 April 2004. Photograph: Uriel Sinai/Getty Images

The Israeli authorities barred Vanunu from giving interviews. When a BBC documentary team spoke to him and then smuggled the footage out of Israel, the authorities reacted by effectively expelling the acting head of the BBC’s Jerusalem bureau, Simon Wilson, who was not involved in the interview.

The dispute rolled on for months before the BBC eventually bowed to an Israeli demand that Wilson write a letter of apology before he could return to Jerusalem. The letter, which included a commitment to “obey the regulations in the future”, was to have remained confidential but the BBC unintentionally posted details online before removing them a few hours later. The climbdown angered some BBC journalists who were enduring persistent pressure and abuse for their coverage.

Later that year, Thompson visited Jerusalem and met the Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, in an effort to improve relations after other incidents.

Pro-Palestinian protesters outside CNN’s office in Washington DC on 17 December 2023. Photograph: Probal Rashid/LightRocket via Getty Images

The Israeli government was particularly unhappy with the BBC’s highly experienced Jerusalem correspondent, Orla Guerin. The Israeli minister for diaspora affairs at the time, Natan Sharansky, accused her of antisemitism and “total identification with the goals and methods of the Palestinian terror groups” after a report by Guerin about the arrest of a 16-year-old Palestinian boy carrying explosives. She accused Israeli officials of turning the arrest into a propaganda opportunity because they “paraded the child in front of the international media” after forcing him to wait at a checkpoint for the arrival of photographers.

Within days of Thompson’s meeting with Sharon, the BBC announced that Guerin would be leaving Jerusalem. At the time, Thompson’s office denied he acted under pressure from Israel and said that Guerin had completed a longer than usual posting.

Chris McGreal writes for Guardian US and is a former Guardian correspondent in Washington, Johannesburg and Jerusalem. He is the author of American Overdose, The Opioid Tragedy in Three Acts

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I wanted to ask if you would consider supporting the Guardian’s journalism as we enter one of the most consequential news cycles of our lifetimes in 2024.

With the potential of another Trump presidency looming, there are countless angles to cover around this year’s election – and we'll be there to shed light on each development in the 2024 election, with explainers, key takeaways and analysis of what it means for America, democracy and the world.

From Elon Musk to the Murdochs, a small number of billionaire owners have a powerful hold on so much of the information that reaches the public about what’s happening in the world. The Guardian is different. We have no billionaire owner or shareholders to consider. Our journalism is produced to serve the public interest – not profit motives.

And we avoid the trap that befalls much US media: the tendency, born of a desire to please all sides, to engage in false equivalence in the name of neutrality. We always strive to be fair. But sometimes that means calling out the lies of powerful people and institutions – and making clear how misinformation and demagoguery can damage democracy.

From threats to election integrity, to the spiraling climate crisis, to complex foreign conflicts, our journalists contextualize, investigate and illuminate the critical stories of our time. As a global news organization with a robust US reporting staff, we’re able to provide a fresh, outsider perspective – one so often missing in the American media bubble.

Around the world, readers can access the Guardian’s paywall-free journalism because of our unique reader-supported model. That’s because of people like you. Our readers keep us independent, beholden to no outside influence and accessible to everyone – whether they can afford to pay for news, or not. If you can, please consider supporting us just once from $1, or better yet, support us every month with a little more. Thank you.

Betsy Reed

Editor, Guardian US