The Long Struggle To Read in Alabama’s Prisons

Cayce Moore was just 19 years old when he found himself in solitary confinement, alone in a dark and filthy cell in Alabama's infamous Kilby prison. His four months in solitary, or "segregation" as it's called by the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC), marked the beginning of his life sentence, now in its 35th year.

The year he arrived was 1987, a time when prisoners in any type of segregation were not allowed to receive magazines, newspapers, or books. When this reality dawned on Cayce, compounded by the squalid surroundings and shouts from other prisoners, he experienced overwhelming alarm. "Confined to a cell 23 hours each day, what was there to do?" he remembered. "How could one occupy the mind or still the fear, despair, and loneliness that filled me?"

Cayce had always been an avid reader, beginning as a small child, "devouring everything from dinosaur books and science fiction to astronomy and encyclopedias," he wrote in one of many letters he's sent me over the years. Today Cayce is 53, incarcerated at St. Clair prison in Springville. We met in 2014 through my reporting on Alabama's prison crisis, but I now consider Cayce a dear friend.

I have sent him many books over the years that we've discussed, and we share a necessity for the written word. Reading is like breathing, an essential part of life itself, but a vast difference in access and opportunity exists between my reading life as a free person and the impoverished reality he faces as an incarcerated person in Alabama.

Cayce was a gifted student from the small town of Ragland, Alabama, but during adolescence he developed crippling depression that went undiagnosed. At age 17, he was considering suicide but instead robbed a local convenience store with two of his friends, also teenagers, and shot the clerk during the robbery. He was tried as an adult and spared the death penalty, but his sentence of life without parole felt akin to death. It meant he would spend the rest of his natural life in prison with no hope of release.

The confines of that solitary cell at Kilby, the beginning of Cayce's lifetime incarceration, still burn in his memory. A single bulb recessed in the back wall of the cell cast the only dim light. It was late September, unseasonably warm, and during the day the cell was stifling. By November, it was freezing at night, so cold that he ate his breakfast, delivered at 4 a.m., swaddled in a single, thin blanket.

Cayce Moore

His lifeline during the dawn of his imprisonment was a college professor named Ada Long. She ran the honor's program at University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), where Cayce had been her student before he was tried and convicted of murder. Ada began writing to him in prison and sending him material to read. Segregation rules wouldn't allow her to send him an actual book, so she photocopied material by Samuel Johnson, Stephen King, and one of her favorite novels, "Housekeeping" by Marilynne Robinson. She mailed it 40 to 50 pages at a time, like a serialized Dickens novel in the 19th century. "Receiving the book in installments made it last longer and I savored every page," Cayce wrote.

Another book Ada sent was "The Queen's Gambit" by Walter Tevis, now a popular Netflix series. Before he was sent to prison, Cayce often played chess with other UAB students inside the Honors House on campus. Ada had earlier advised Cayce that he should think of his life in prison as a game of chess. "By applying my mind in a clear-headed, systematic way, I could learn to survive and perhaps thrive," he remembered.

Back in 1987, ADOC mailrooms were looser on page restrictions, but now the agency imposes a four-page limit for photocopied material sent through the mail, and anything longer is rejected. But those early books Ada sent gave Cayce something constructive to do with his mind when the only other option was to ruminate on his devastating circumstances. "I can't imagine what that experience would have been like for me without Ada's support and the regular stream of reading material she sent my way," he wrote. "I think she saved my life."

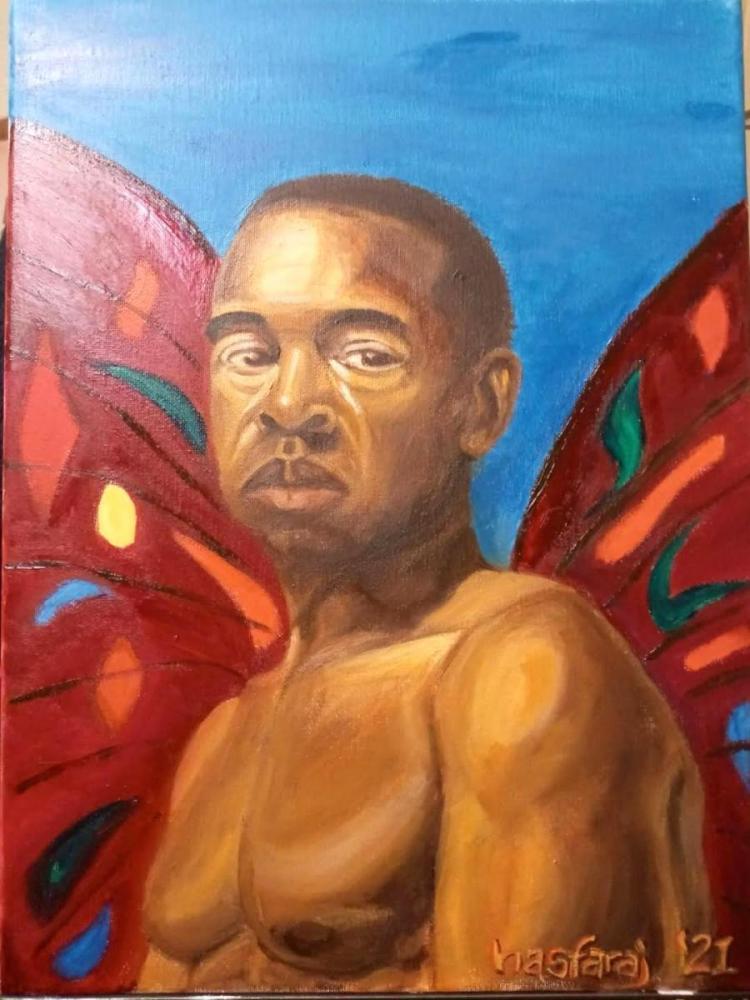

Another fellow reader and writer I have gotten to know over the years is Hasani Jennings. Like Cayce, Hasani has spent his entire adult life in prison for a fatal shooting he committed during a robbery when he was a teenager. Hasani grew up poor, in and out of the custody of his mother who suffered from mental illness. Although he was a gifted student, his grades began to suffer, and as an adolescent he began drinking heavily before he committed his crime.

In 1994, he was cast into Alabama's prison system with no hope of release. Today he is 48. Books have provided therapy to Hasani, a pathway to understanding himself and the larger world that he can no longer access. "I started surrounding myself with books shortly after I woke up in prison," he explained, "and set out on a mission to find the self I lost. I can't imagine doing time without books."

'Books is contraband'

In 2018, Hasani was suddenly transferred without explanation from Donaldson Prison, where he'd lived for a decade, to Limestone Prison in North Alabama. When a prisoner who worked for the officers told him to pack up, Hasani didn't ask where he was going. "I asked him how many books I could take," he wrote. "He said four. It reminded me of when I was 9 years old, and our apartment burned up. That same deflating feeling of loss, but at least this time I could choose something to take with me."

Self-portrait by Hasani Jennings

Hasani chose two books for his studies of the French language: "Complete French Grammar" and a French-English dictionary. He also brought a collection of essays by Ta-Nehisi Coates titled "We Were Eight Years in Power," and his Hebrew/Greek Bible. When he arrived at Limestone, officers confiscated the Bible because it was worn and had a replacement cover, something they claimed created a security hazard. It was another loss to remind Hasani that he was powerless to stop the prison's infantilizing control over his entire life and property.

Cayce and Hasani are just two men among thousands of people struggling to survive the record violence and chaos of a prison system in crisis. In December 2020, the United States Department of Justice sued ADOC after the two sides failed to agree on remedies for unconstitutional excessive force and bloodshed. In addition to horrific overcrowding and skyrocketing deaths, ADOC's long history of restricting the constitutional right to read reflects a mindset intent on inflicting the harshest punishment possible.

From banning books to barring lending libraries to enforcing draconian practices like allowing only the Bible as reading material for people in disciplinary segregation, ADOC has long eyed educational opportunities with suspicion and sought to suppress access to reading material. These practices are part of the larger story about how Alabama prisons descended into the current morass and why Gov. Kay Ivey's "Alabama solution" of constructing new mega-prisons will not address the pervasive punitive and dehumanizing ethos behind the crisis.

Perhaps no other case embodies this outrageous oppression like Johnson v. Mitchem, a 1997 lawsuit filed after the warden of Donaldson prison created a list of acceptable reading material that limited books, magazines, and newspapers in the prison to a paltry 16 publications. Steve Dees, a career correctional employee, decided periodicals such as Scientific American, Inside Chess, Writer's Digest, and hundreds of others would no longer be allowed inside the maximum-security prison. "Books is contraband," Warden Dees said in a deposition, revealing a truth about ADOC rarely stated so explicitly: that reading while incarcerated was seen as dangerous by the prison administrators who went as far as authorizing book burnings in a field near Donaldson prison.

The deposition occurred after attorney Rhonda Brownstein with the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) in Montgomery, Alabama, filed the lawsuit in response to the warden's arbitrary attempt to ban reading material, arguing the policy violated the First Amendment and served no logical security purpose. The judge agreed, forcing prison leaders to withdraw the ridiculous policy, but only after ADOC attempted to defend the warden's position, wasting precious taxpayer dollars on needless litigation.

'My mind could be free'

Instead of allocating resources to better staffing and training, or more extensive therapeutic and educational services, ADOC continues this pattern of wasteful legal spending, defending unwinnable causes and fighting reforms at every turn.

The class-action lawsuit, Braggs v. Dunn, now in its eigth year of litigation, already determined that mental health care in ADOC is "horrendously inadequate." Despite the fact that the state's prison system has the highest suicide rate in the nation, Alabama leaders have approved over $28 million in taxpayer-funded legal spending to defend ADOC since the case was filed in 2014. In December, a federal judge issued an order in the case requiring ADOC to remedy the situation, saying that its "horrendously inadequate" care of mentally ill inmates violates the U.S. Constitution's ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

In early 1988, after Cayce was released from his four-month stay in segregation, he entered the prison's general population and soon realized the scarcity of books was not just a segregation problem but a problem throughout the entire prison. Other than a few old paperbacks floating around the cell blocks, there was no centralized prison library or set of books available to everyone.

Cayce was soon hired to work in the prison chapel, performing clerical and custodial duties, but he also convinced the chaplain to allow him to set up a religious library. He wanted to offer a broad selection of religious material covering several Christian denominations, and some material for the small Muslim community in the prison. The chaplain allowed Cayce to solicit donations for educational and reference books, like dictionaries and encyclopedias, along with biographies, classical literature, and even popular fiction that he didn't consider "trashy."

Once again, Ada Long was an invaluable ally, securing donations from UAB. Cayce remembers reading some great books during this period — "The Color Purple" by Alice Walker, "The Bluest Eye" by Toni Morrison, "Things Fall Apart" by Chinua Achebe, "The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat" by Oliver Sacks. "Even when my body was in prison, my mind could be free through books," he said. "We ended up with a decent library — about 300 books." Dozens of men began visiting the library and checking books out. Things went well for about a year, until one day in 1989 when guards locked down the entire prison to search for contraband.

An officer named Sgt. Brown searched the chapel, "a hateful man who viewed any kind of educational or rehabilitative program for prisoners as 'coddling criminals,'" Cayce wrote. Brown confiscated all the nonreligious books and sent them out the back gate of the prison where officers threw them into a dumpster. Cayce watched through a window in his dorm as officers carried garbage bags and cardboard boxes to the dumpster, a sinking feeling of dread in his gut.

That same day, Cayce was called to the chapel. He was met by Brown, a bulldog of a man, an angry look on his wide face. "I'm going to write your ass up," Brown said. "For what?" Cayce asked. "For running an unauthorized library," Brown snarled.

The warden vouched for Cayce and the disciplinary citation was never written, but the books were gone forever. "Reading was hard to come by after that," Cayce told me. "I felt frustration and anger at the irrationality of the system. They seemed hellbent on making it so difficult for people to get books."

'Like tending a garden'

Instead of wallowing in despair, Cayce focused his attention on an area of the prison known as "the school," where Lawson State Community College taught adult basic education. The area contained a large room meant to be a library, but it was in shambles, an embarrassment to the prison administration because dignitaries touring the prison often caught a glimpse of the disarray. "Picture a huge room with several thousand books randomly dumped into piles on teetering stacks of cardboard boxes," he described.

Cayce pitched the idea of cleaning up and organizing the library, then opening it to the general population. The warden approved the project on one condition: Cayce and the other prisoners who would set it up had to make it look good and organize it like a real library.

To catalog all 5,000 books, Cayce borrowed a set of Dewey classification manuals from UAB. He recruited four other prisoners to work with him on the project, which took about two months. When they finished, the library became a showcase for the prison. Cayce explained that creating and maintaining a library or educational space inside a maximum security prison is often a political process that must be carefully managed. It needs to benefit both the prisoners and the administration in some way, and it must be defended from negative elements in both groups.

"It's like tending a garden," Cayce wrote. "You have to nourish the good, useful plants and continuously fight the weeds. Libraries can be exceptional spaces in a prison, but you've got to have some staff on board to intercede against people like Sgt. Brown. Some staff will just see it as a good way to control prisoners, but others see the human benefit. The key is to have some staff that are true believers to set it up and make it work. You have to keep them convinced that it's a good thing."

In 1991, ADOC secured a grant to set up libraries in multiple facilities. Donaldson would be the first Grant Library Service (GLS) location in the prison system, and Cayce and his friends were thrilled. This meant they could greatly expand the limited selection of books they had. ADOC hired a trained librarian who set them up with about 1,200 books, including encyclopedias and other reference books, plenty of novels in popular genres, and a decent selection of literary titles, along with several hundred nonfiction works like biographies, history books, and vocational manuals.

A major point of contention was how to handle service for prisoners in segregation. Cayce believed those in solitary confinement needed access to books, but the warden was skeptical. Ultimately, the warden decided the library would run a book delivery service to everyone in solitary confinement, including death row, except for people serving time in segregation as punishment for disciplinary infractions. The book cart would never enter that unit.

Cayce served as the primary person to fulfill book orders for those in protective custody and on death row. He didn't have direct contact with the men, but he got to know them through the books they requested on slips of paper listing their primary and alternate requests. He never got farther than the door of the death row unit, but sometimes when he dropped off orders, he would glance through the large glass windows and spot one of the men sitting outside his cell. Occasionally, one would wave or give Cayce a thumbs up. After a while, some of the men on death row began adding short notes to their requests. "Thanks, man!" or "Great book!" or "Love this author, got anything else by her?"

When Cayce couldn't find any of the books a man requested, he tried hard to substitute something similar, or at least pick something he knew was good. "I knew the clock was ticking for those guys," he wrote. "They had a limited time left to read. It was on me to try to find something that this guy would enjoy. It mattered to me."

It turned out some of the men on death row, like Cayce, were big fans of the "Wheel of Time" fantasy series by Robert Jordan, so Cayce loaned part of his personal collection to them, making sure all of them got a chance to read it. One sent a note back that he'll never forget. "Thanks for sharing your books with us," the man wrote. "This has been a great series! Hope I get to finish it before my time comes."

Cayce thinks GLS lasted about four years, until the grant ran out and subsequently the libraries declined. The end of GLS meant the individual prisons no longer had to report to a central library authority and they stopped receiving regular book shipments. Without that oversight, the leadership inside ADOC failed to maintain the momentum. "Most of the people in charge of ADOC's prisons don't appreciate or even understand the value of quality libraries for prisoners," Cayce wrote, "and probably not even the value of books themselves."

A four-book limit

ADOC rules contain a list of 13 approved items that prisoners may have in their cells, along with the number allowed — 40 stamps, three black or blue ink pens, four notepads, one calendar. Under books, the rules state, "Four total to include Bible or equivalent religious study book, educational/dictionary, law book, and/or novel." The books are to be kept within a locker box under the bunk. The list governs "all inmate personal and state-issued property," and anyone who violates it is subject to disciplinary action.

Despite these rules, Hasani has maintained an elaborate book storage system in his cell at Limestone, which he described to me in a recent letter.

"Books stretch across the top rail," he wrote. "I glued rectangular wooden blocks on the wall to make a shelf. There's another bookshelf made from a net laundry bag. It has three levels — big pockets sectioned off with strings from an old state-issued boot. Stray books are in my locker box. Under the bed, there's a bag filled all the way to the top with books. There's another bag just like it under there, half filled with books and half with legal work. There are two stacks of books and papers under there, another stack growing in the front corner by the wall. Plus, I've got a dozen out on loan."

Hasani knows he's taking a chance keeping so many books in his cell, but to him it is worth the risk. "Officers generally don't care about that offense, but I know all it takes is one to come to work with a bad attitude," he wrote. "Knowing I can lose them all at any time makes me put more effort into internalizing what I read and study, and into applying it to produce as much good as I can in the world."

Hasani began reading in prison to stimulate his mind. He started with self help books that his cellmate shared with him — "The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People" and "Don't Sweat the Small Stuff." He was excited to read about ideas that he could apply to his life to make himself better, a little more capable of enduring his incarceration that buried him alive. "My reading was slow and labored," he remembered. "I needed grammar and vocabulary work. But the more I read, the more alive I became."

He moved on to books about Christianity and spirituality, to novels and essays and anything he could get his hands on. Today Hasani prefers practical books like "The Personal MBA" by Josh Kaufman, but he also has a long list of favorite literary novels like "Their Eyes Were Watching God" by Zora Neale Hurston. After he picked up reading, he went on to serve as a literacy tutor for many years, teaching other incarcerated men to read.

By the time Hasani left Donaldson in 2018, the prison's central library was long gone. He connects ADOC's indifference toward libraries as a symptom of larger dysfunction within the agency. "The Alabama DOC doesn't see libraries or books as a priority," he told me. "It's not a coincidence that guys misbehave or do drugs because there's nothing available in here. If they (ADOC) were to promote education, personal transformation, or rehabilitation, then that's how people would spend their time."

When incarcerated people "misbehave," they are often subjected to time in segregation, but it's not just used for disciplinary purposes. "Administrative segregation" is a catchall term ADOC uses for nonpunitive stays in solitary, like Cayce's four-month stint at the beginning of his incarceration. In 1995, the issue of periodicals in administrative segregation became the subject of a lawsuit. A man named John Spellman, who was confined in administrative segregation at Donaldson, decided to sue over the ADOC policy, which began in 1987, banning magazine and newspaper subscriptions in administrative segregation. Spellman alleged that prison staff confiscated and destroyed his magazines and books when he was placed in segregation, and he believed this, along with the prohibition of receiving subscriptions, violated his First Amendment rights.

All segregation cells are the same — single occupancy, a concrete room the size of a standard parking space, with only a bunk and a metal combination toilet and sink. Incarcerated people can be confined to administrative segregation for long or indefinite periods of time. When he filed the lawsuit, Spellman had been sent to administrative segregation on five different occasions "for his protection," and he was hardly alone. In April of 1997, 600 to 700 men and women were in administrative segregation throughout ADOC, and a total of 1,500 to 2,000 were in all categories of segregation.

Spellman testified that he spent over 23 hours a day in his cell, released only to shower or exercise in the prison yard, which the judge described as "walking around in a circle with their hands handcuffed behind their backs in the yard, which is usually a small concrete fenced-in area." Spellman told the judge, other than writing letters, working on legal matters, or cleaning his cell, "there's just not much to do, really."

U.S. District Judge Ira DeMent, who died in 2011, wrote in his Spellman v. Hopper order that "inmates have a First Amendment right to receive newspapers and magazines through the mail." While ADOC attorneys argued that limiting reading material in administrative segregation was vital to safety, security, and discipline, Judge DeMent didn't buy it, finding the restrictions to be "an exaggerated response" to concerns in the prison. He called the reading choices in administrative segregation "profoundly limited" and wrote that the restriction "offends the Constitution even under the most deferential standard."

ADOC was forced to apply the same standard to administrative segregation that existed in other parts of the prison: to limit the quantity of newspapers and magazines without absolutely banning them. The decision was a victory for Spellman and people incarcerated throughout Alabama, but the litigation took five years to resolve.

Burning books

While Spellman was winding its way through court, another issue involving publications bubbled up inside the prisons.

In 1997, Steve Dees became the head warden at Donaldson after 20 years of working for ADOC. Dees was close to retirement, but he still wanted to strictly curtail the number of periodicals coming into the prison. He issued a new policy on March 19, 1997, that banned all magazines not included on his pre-approved list, which originally contained only five magazines but that he later expanded to 16. The new rule also permitted prisoners to subscribe to newspapers only from their hometown. Cayce recalled that Dees also made the statement that all books except those checked out from the prison's library were contraband, the Bible being the sole exception.

The people incarcerated at Donaldson, especially avid readers like Cayce, felt blindsided by the new rules. At the time, Cayce subscribed to The New York Review of Books, The New York Times Book Review, Harper's, The Atlantic, Chess Life, Inside Chess, Paper Mayhem, Science News, and Scientific American, none of them on the approved list. "So, the mailroom promptly stopped allowing me to receive my magazines," Cayce wrote. "All of this gave us the opportunity to file a lawsuit with the objective of restoring access to periodicals and leveraging the absurdity of the rule to establish a realistic procedure for inmates to order their own books."

Once again, Rhonda Brownstein at SPLC agreed to file the lawsuit, and Cayce did some of the footwork inside the prison. In a deposition of Dees by SPLC's Ellen Bowden on June 26, 1997, Dees admitted the policy was really enacted to address staffing issues in the prison mailroom. "The volume was too big for one person to handle," he said.

In this same deposition, Warden Dees revealed that he did not know how many men at Donaldson subscribed to magazines, or which magazines were available in the prison's general library. He also had no idea how many prisoners didn't know how to read, how many were enrolled in literacy classes, or how the prison obtained books for the general library. He said he came up with the policy to cut back on "an excess amount of paper in the prison" and to address staffing shortages. When Bowden pressed him about the need for the policy, he said his list of acceptable magazines meant "less stuff we'd have to put up with" in the cells.

Q: How did you decide which magazines inmates would be permitted to receive?

A: I used my own judgment on it.

Q: How did you decide which magazines would be on the final March 19th list?

A: Past experience.

Q: Why can't inmates receive magazines that are not on this March 19th list?

A: Because we feel that's all the magazines they need.

Q: Why do you feel these particular magazines are the only ones inmates need?

A: That's the ones we've always had. That's the ones we had when I first started, the ones we had I was trained to bring in, and that's the way we still do it.

Dees also told Bowden that every night, officers shook down 10 different people to look for rule violators and contraband.

Q: And that includes books in particular?

A: Yes ma'am. Not in particular. Books is contraband.

Q: What do guards do with those books?

A: Some of them are destroyed and if the inmate says, 'put it in the general library,' we put it in the general library.

Q: What do you mean when you say 'destroyed?'

A: Destroyed.

Q: It's burned?

A: Burned. Fill an incident report out and burn it.

Q: Where are those books burned?

A: In the field over there (indicating).

Censorship by bureaucracy

After several months of depositions in Johnson v. Mitchem, it became clear to Warden Dees and ADOC that they would not prevail. Dees withdrew the policy and the two sides agreed to settle the matter without a trial. "After the settlement, things got better for a while," Cayce remembered. "People started getting their magazines and newspapers again, and since the settlement allowed us to receive book catalogs (this was before Amazon), we were allowed to order books more easily."

The plaintiffs made one concession. They agreed to allow ADOC to keep its rule that incarcerated people had to pay for books out of their "Prisoners' Money on Deposit" or PMOD accounts. This meant no one outside the prison could directly order books for prisoners. The PMOD accounts contain the only official money an incarcerated person is allowed to maintain or spend while in prison. Family or friends can deposit funds into the account using a credit card or money order and the transaction is managed by ADOC's business office.

Rhonda Brownstein realized this rule was a big problem when she wanted to send Cayce the newest book in Robert Jordan's "Wheel of Time" series, but couldn't order it for him because the PMOD rule required that Cayce pay for it with the funds in his account. Rhonda offered to send him the money, but that wouldn't work either because ADOC also required that prisoners order books directly from the publisher, vastly limiting their choices. Cayce had not been able to find a book catalog that listed the "Wheel of Time" series.

"It's difficult to describe the feeling of wanting a particular book, knowing that it exists and having the means to purchase it, but being utterly unable to get a copy and read it because of impossible bureaucratic procedures," Cayce wrote. "The truth masked by all those rules was that prison officials knew that we were legally entitled to obtain and read books, but they didn't want to deal with the minimal hassle of processing books in the prison mailroom."

Rhonda searched for ordering information for Cayce, but she turned up empty handed. "The other shoe dropped when the mail clerks at Donaldson realized they could apply the PMOD rule to periodicals as well as books, and everyone in the prison was given one month to prove they had ordered their magazines or newspapers using funds in their PMOD accounts," Cayce wrote. "Almost no one had and then once again, all the periodicals were rejected."

Cayce and Rhonda discussed filing a lawsuit, but they knew it could be a hard fight because ADOC could argue that prisoners could pay for books and periodicals with their PMOD funds. ADOC wasn't outright banning publications — they just made getting them as difficult as possible. "I decided the best approach would be to amplify the effect of edge cases, specifically free publications that literally couldn't be purchased," Cayce wrote.

To work this angle, Cayce wrote an article for Prison Legal News, which entitled him to a free issue and allowed him to bring Prison Legal News on board as a plaintiff. He also identified prisoners who were receiving free religious or self-help books, and he asked people to send off for free government publications, vocational materials, Dianetics booklets, anything he could think of that wouldn't cost a penny. "Before filing anything in court, I built a weapons-grade case against ADOC, guaranteed to make them look like book-burning fools," Cayce wrote.

ADOC wardens defended the PMOD policy, citing security, but no real specifics. In a deposition, Gwendolyn Mosley, the warden of Easterling prison, claimed the policy was designed to prevent a scheme of incarcerated people using magazine subscriptions to pay off drug debts, but then admitted she didn't know of a single case in which that had happened. "I just think it's a good security practice to limit them and confine them," Mosley said.

At the first meeting between both sides, Cayce recalled that the magistrate told ADOC their case was absurd and they needed to settle. The settlement finally ended the PMOD rule; since then, receiving books ordered by friends and family from places like Amazon has been a relatively smooth process. However, ADOC employees can still reject hardback books or any publication they think violates the standards of prison regulations, although the agency does not make those standards publicly available.

A failed agency's rotting heart

In September 2010, those mysterious standards led to a lawsuit and an avalanche of unfavorable media coverage for ADOC.

Staff at Kilby Prison would not allow a man named Mark Melvin to receive the Pulitzer Prize winning book "Slavery by Another Name" by Douglas Blackmon, a widely acclaimed work examining the forced labor of prisoners in Southern states through the convict leasing system from after the Civil War until World War II. An officer cited the ADOC regulation preventing mail that poses a security threat, calling the book "too incendiary" and "too provocative." Melvin filed a grievance, but the prison swiftly denied his plea. Melvin then filed a lawsuit, arguing ADOC's actions violated his constitutional freedom of speech, due process, and equal protection.

"Defendants' decision to ban the book was based on their desire to restrict access to information about historical racism in the Southern United States and is not reasonably related to a legitimate penological purpose," attorneys with the Montgomery, Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) argued on behalf of Melvin. ADOC, represented by Alabama's attorney general, admitted that prison officials banned the book based on its subject matter and defended the action. "The book, its title, its contents and/or its pictures could be used (or misused) by the plaintiff or other inmates to incite violence or disobedience within the institution," the attorney general wrote.

As a result, more than 50 media outlets publicized ADOC's decision to ban the book and deny the incarcerated population critical information about America's racial history. Headlines included "Book is too embarrassing for Alabama prison," and "Black history and the art of denial." Public outrage grew as the case continued to wind its way through court, but finally in 2013 ADOC agreed to lift the ban on the book and EJI dropped the lawsuit.

The need for more informed thinking about all aspects of incarceration underpins Alabama's continued indifference to the crisis in state prisons. The governor and ADOC have focused energy exclusively on new buildings, while prison libraries have languished or closed and participation in prison educational and rehabilitative programs has plummeted. In the last decade, graduates of ADOC's re-entry program have dropped by more than 50%, prisoners earning a GED have fallen by more than 60%, and people completing ADOC's drug treatment program fell more than 70%.

For Cayce, the decades-long struggle to read is just one piece of an epically difficult life behind the walls of prison, run by an organization that relies on institutional violence and oppression, with the goal to always keep the prison population disenfranchised and in its place. The consistent disregard of prisoners' humanity can lead people in charge not only to ban books but also look the other way when prisoners are using substances, taking their own lives, and dying in record numbers.

"The critical component is the decline in ability and integrity of supervisors managing the prisons," Cayce wrote. "The same problem that lies at the rotting heart of the entire failed agency."

Beth Shelburne is an independent journalist and writer based in Birmingham, Alabama. She is currently an investigative reporter with the Campaign for Smart Justice and spent 20 years working as a television reporter and anchor.

Facing South is the online magazine and every-other-weekly email newsletter of the Institute for Southern Studies, featuring investigative reporting and in-depth analysis of trends across the South. Facing South has earned a national reputation for exposing abuses of power, holding powerful interests accountable, and elevating the voices of everyday people working for change in the South.

Facing South was launched as an email newsletter in 2000 by the Institute for Southern Studies, a research, media, and education center based in Durham, North Carolina. From 1973 to 2010, the Institute published the award-winning print journal Southern Exposure.

The Institute’s public-interest media programs have won many prestigious awards, including two George Polk Awards, a National Magazine Award, and honors from the National Press Club, N.C. Press Association and White House Correspondents’ Association.

Your donation supports Facing South's fearless reporting exposing injustice and attacks on democracy. Your support also makes possible the Institute's special programs like the Julian Bond Fellowship, which trains new journalists working for democracy.