Operation Dixie Failed 78 Years Ago

Volkswagen workers’ decisive recent union election victory in Chattanooga, Tennessee, makes them the first Southern U.S. auto workers to unionize a foreign-owned auto factory. Their success could also mark a historic turning point for generations of Southern workers seeking to improve their jobs and transform their states’ economies.

There are also signs that vigorous enforcement of federal labor law and other pro-worker federal policies, bolstered by the Biden administration, are contributing to a more level playing field for workers attempting to organize in the South.

But a long history of exploitation will take a strong, national labor movement to overcome. For decades, Southern state governments have promised corporate employers the opportunity to profit from the exploitation of local workers. The promise has hinged on a package of state policies designed to enrich the powerful few and maintain economic and racial inequalities, at the expense of all workers. As detailed in a new series of EPI reports, this Southern economic development model has been characterized by low wages, low corporate taxes, lax regulation of businesses, and extreme hostility toward unions.

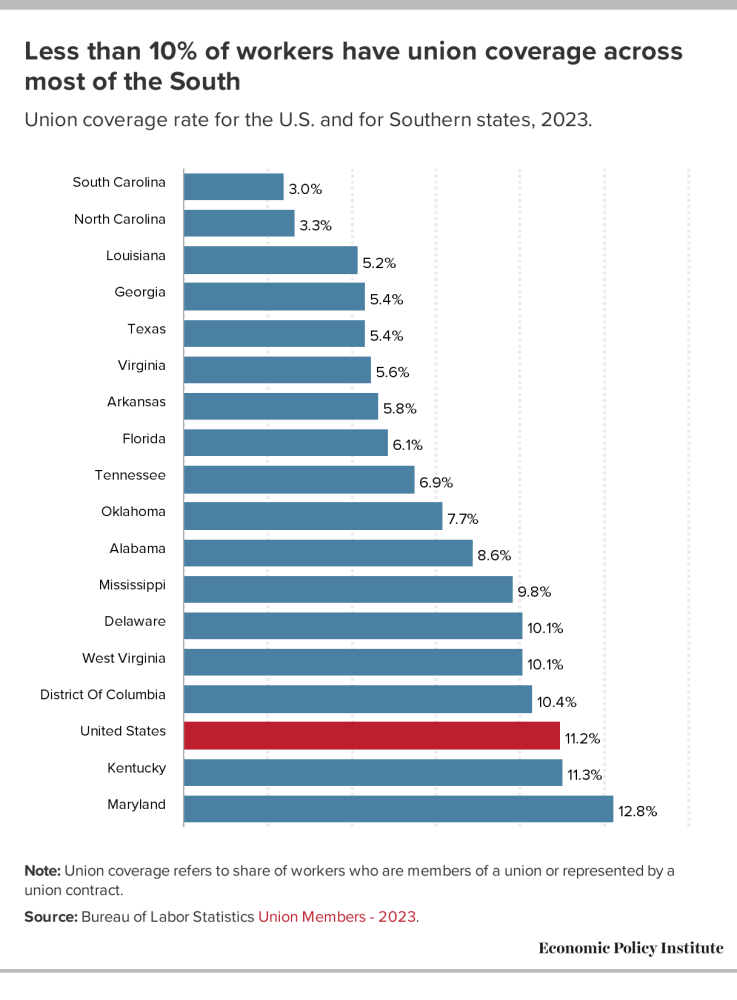

Despite this hostility, generations of Southern workers have fought to organize unions, at times achieving important but limited success. More often, intense employer repression of unions has blocked or crushed Southern workers’ organizing efforts, while state lawmakers have enacted policies to restrict collective bargaining rights in the South. As a result, Southern states have some of the lowest rates of union coverage in the country. Figure A shows that, while union coverage rates stand at 11.2% nationally, rates in 2023 were as low as 3.0% in South Carolina, 3.3% in North Carolina, 5.2% in Louisiana, and 5.4% in Texas and Georgia.

Perhaps the most ambitious of past efforts to organize Southern workers was Operation Dixie, launched 78 years ago this month, when multiple unions committed to organizing millions of workers in major Southern industries. Though well-resourced and determined, the unions that embarked on Operation Dixie were ultimately defeated by Southern economic and political elites, who used state power to assist employers in opposing unions while stoking racism to divide Black and white workers.

The failure of Operation Dixie allowed Southern elites to further entrench racism and exploitation in state economic policies for subsequent generations. Today, however, emerging successful efforts to organize Southern workers—despite familiar opposition from employers and Southern Republican elected officials—suggest that the present could be a new moment of opportunity for workers to build the collective power necessary to upend the failed Southern economic development model.

May 1946: the start of Operation Dixie

Labor unions in the United States emerged from World War II as powerful as they had ever been. A third of all U.S. workers were in unions, and their gains set the stage for an unprecedented 30-year increase in living standards—the likes of which had never been seen before. Black workers, then as now, were more likely to be unionized than white workers, and despite ongoing racism even within labor’s ranks, unions helped reduce racial wage gaps.

Organized labor’s weak link was the South, where fewer than 10% of workers were unionized. Labor leaders knew that as long as a major region of the country remained so bereft of unions, there was a risk that companies would be drawn to this region to avoid unions.

The leaders of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) recognized that a major effort to organize the South was necessary. Backed by millions of dollars and more than 400 professional organizers, they launched their campaign in May 1946. As Barbara Griffith details in her seminal book, this was the biggest organizing drive of the postwar period.

But as soon as it began, Operation Dixie ran into the same three obstacles that have long plagued efforts to organize Southern workers: government hostility, corporate union-busting, and racism.

Southern state and local governments were almost uniformly anti-union. Florida and Arkansas had, in 1944, been the first states to pass so-called right-to-work laws designed to suppress union membership, and other Southern states soon followed. Police routinely raided union halls and arrested labor organizers for activities like passing out leaflets in front of factory gates or standing on a street corner with signs. A CIO organizer in Mississippi who tried to ask the FBI to intervene was arrested by local police. In Parsons, Tennessee, the town mayor led a mob of 50 men to an outdoor union meeting and ordered the organizers to leave town. Again and again, Griffith records, Southern governments combined anti-worker policies with forceful (and sometimes violent) uses of state power to prevent unions from gaining a foothold.

The resulting environment provided sanction to corporations’ aggressive and frequently illegal union-busting practices. When a majority of workers at a small textile company in Jasper, Alabama, signed union cards, the company fired them all; when the workers struck in response, the company closed the plant. The Grove Stone and Sand Company in Black Mountain, North Carolina, fired its entire second shift when they organized. Two women organizing with the CIO in Tennessee were confronted by a mob of over 150 men and ordered to leave town. To be sure, unions pursued legal remedies for many of these cases through the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), but such efforts were no match for the overwhelming tide of illegal union-busting across the region.

Corporations and state and local governments also sought to entrench white supremacy and sow racial division wherever possible. The CIO recognized from the beginning that Operation Dixie could only succeed if unions persuaded white workers that solidarity with Black workers was their best path to a better life. This proved a difficult challenge. As Griffith’s book describes, CIO organizers were shot, a striking Black worker in Arkansas was killed by a strikebreaker, and county sheriffs and their deputies were often members of the KKK. Beyond overt acts of violence, every anti-union campaign launched by corporations or governments highlighted the supposed threat to white workers posed by Black workers and played upon deeply racist myths about Black men threatening white women.

Racism and exploitation further entrenched

While efforts carried on until 1953, Operation Dixie was largely defeated in its first months. Though the unions had fought very difficult fights before then, they found the South to be too hostile. Operation Dixie ultimately organized very few workers despite devoting massive sums of money and years of effort in attempts to support heroic groups of workers trying to exercise their federal labor rights in the face of extreme employer and government hostility in the South.

In the decades to come, Southern states continued to enact policies hostile to worker power and labor rights. Most Southern states do not have a minimum wage higher than the federal wage of $7.25 an hour. Most Southern states eventually passed so-called right-to-work laws, as well as laws preempting the right of local governments to pass pro-worker policies, like minimum wage increases. Southern states greatly restrict the rights of public employees to unionize, and public employee compensation in the South is consequently quite low. More recently, Southern states have been lifting restrictions on child labor, and enacting legislation to punish employers who voluntarily recognize unions.

As our Rooted in Racism series shows, these policies have resulted in the worst economy for workers and their families in the country. Poverty is high, wages and employment rates are low, and racial wage and wealth gaps are persistently large. Without unions to help counterbalance the power of corporations, the Southern economic development model has continued to degrade working and living standards for all Southern workers.

Signs of hope

While state and local governments in the South were hostile to Operation Dixie, the federal government could have been an ally. President Truman was a pro-labor president and labor laws protecting unions in 1946 (prior to damaging amendments passed in 1947) were in many ways stronger than they are today. The federal government had used the awarding of defense contracts during World War II to encourage unionization. And during the war, massive mobilizations for equal employment opportunity spearheaded by Black leaders of unions like the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters pushed the Federal Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to take modest but real steps in the direction of desegregating vital industries. Despite this recent record of intervention, the federal government did very little postwar to protect workers organizing in the South, during a period of intense business backlash against unions and workers’ wartime gains.

Had the federal government more actively intervened in 1946, it might have gone a long way to counterbalance the many challenges workers faced in organizing the South. By contrast, the current federal government has helped level the playing field for workers attempting to organize in the South by vigorously enforcing federal labor law and other pro-worker federal policies.

For example, the NLRB’s General Counsel, Jennifer Abruzzo, appointed by President Biden, has aggressively worked to uphold the federal law’s mandate to protect workers’ right to bargain collectively. At employers across the South like Amazon, Starbucks, and UPS, the NLRB has assiduously enforced labor law and worked to protect workers from employers who violate the right to unionize. The Federal Trade Commission has banned noncompete clauses that harm worker mobility, and the Department of Labor has raised the threshold for overtime pay for the first time this century. President Biden became the first U.S. president in history to walk a picket line during the 2023 United Auto Workers (UAW) strike and has issued public statements prior to major Southern union elections intended to remind and assure workers that federal law protects the right to organize and leaves the choice of unionizing entirely up to workers themselves.

Just as importantly, major pandemic recovery and industrial policy measures enacted by the Biden administration have contributed to a strong labor market, characterized by low unemployment, rising wages (especially for low-wage workers), and high demand for workers in industries targeted for massive federal investment by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), and the CHIPS Act—especially in the South. The IRA, for example, includes the largest investment in domestic auto production in U.S. history, with $430 billion in subsidies and tax incentives for U.S.-made products. In the next 10 years, economists predict IRA investments and tax credits will lead to the creation of an estimated 9 million jobs, with grants and loans to auto companies creating an estimated 80,000 electric vehicle production jobs alone. In this context, familiar anti-union threats of layoffs or plant closures become far less plausible—and therefore less effective—as an employer tactic to scare workers out of organizing in rapidly expanding Southern manufacturing industries, at a moment of historically low unemployment.

While none of these federal actions come close to fully removing obstacles to workers’ rights posed by weakened federal labor laws (which would require Congressional action to strengthen) and state laws restricting union rights, the combination of important federal fiscal, economic, and enforcement actions may be helping to mitigate some of the most extreme—and historically successful—forms of employer union-busting in the South.

The Southern economic development model, rooted in racism and worker exploitation, has failed to create shared prosperity. While wealthy and powerful people across the South have fought long and hard to maintain racial hierarchies and prevent workers from unionizing, today many Southern workers are calling for a different way forward. At an important moment of economic opportunity, thousands of workers are taking steps to organize strong multiracial unions in the South—and some are already overcoming the formidable obstacles that brought Operation Dixie to a halt decades ago.

While Operation Dixie launched at a time of historically high rates of unionization, today’s unionization rates have fallen to historic lows. Yet worker support for unions is at an all-time high across the country, including in the South. In addition to auto workers, recent Southern worker organizing includes the Association of Flight Attendants’ burgeoning campaign to organize workers at Atlanta-based Delta, Duke University graduate employees becoming some of the first to unionize at a Southern university, hospitality workers voting to unionize at New Orleans’ largest hotel, plus tens of thousands of Virginia educators and public servants unionizing in the wake of state law changes lifting a 40-year ban on collective bargaining for local government employees. Soon, thousands of auto workers at Mercedes’ Vance, Alabama, plant will have their chance to vote in another major UAW union election. While taken together these efforts are, so far, smaller in scale than those envisioned by the architects of Operation Dixie, they represent what could be just the start of the most significant organizing gains in the region in decades.