ANC, and SA Election – Apartheid’s Long Shadows: Two Articles

ANC at a Crossroads as South Africa Goes to the Polls

Steve Bloomfield in Johannesburg

The Guardian

May 26, 2024

https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/may/26/anc-at-a-crossroads-as-south-africa-goes-to-polls-election

It was supposed to be a show of strength, a packed crowd of 83,000 ANC supporters showing South Africa that despite the country’s myriad problems, the ruling party was still confident of victory in Wednesday’s pivotal elections.

Instead, as people streamed out of the three-quarters-full venue before President Cyril Ramaphosa’s speech had even begun, the Siyanqoba (“To conquer”) rally will have left ANC leaders more nervous than ever that the party that liberated South Africa will lose its majority for the first time since Nelson Mandela led it to victory in 1994.

If the ANC’s vote falls below 50% and it is forced into a coalition, it will only have itself to blame. Rampant corruption under Ramaphosa’s predecessor, Jacob Zuma, has hollowed out the state. About four in 10 South Africans are unemployed, while basic public services are either poor or non-existent.

Power and wealth still resides in a tiny minority, while poverty is extreme, making South Africa the most unequal society in the world. It’s also one of the most dangerous.

“Everywhere in the country, crime is the thing that people talk about, whether you’re black or white,” said William Gumede, a political analyst who also helped some of the opposition parties form a pre-election coalition pact. “It deprives South Africans from living a full life. It has sucked the soul out of the country.”

Members of the ANC women’s league attend a party rally. Photograph: Madelene Cronjé

The progress made under the leadership of Mandela and his successor, Thabo Mbeki, stalled when Zuma took power. Billions was looted from the state, leaving almost every part of it bankrupt, from the national airline to the agency that ran the railways. An official inquiry concluded that “the ANC under Zuma permitted, supported and enabled corruption”.

A generational divide is opening up. At Soweto’s FNB stadium – the venue, then known as Soccer City, that hosted the opening game of the 2010 football World Cup – several older rally attendees spoke of their frustration that their children, born into freedom, were not backing the ANC.

On the day of South Africa’s first free election in 1994, Girlfaith Dlamini was nine months pregnant. While her fellow South Africans queued for hours to cast their votes, Dlamini was taken to the front. “I was treated like a president,” she said. Her daughter was born two weeks later, the day after Mandela was sworn in – now she’s studying chartered accounting at Wits University. “My kid is in university because of the ANC. I’m a domestic worker, I couldn’t afford fees.”

But her daughter, like many of those “born free”, has less loyalty towards the party that has ruled South Africa her entire life. On Wednesday, she will vote for the EFF, a leftwing populist party led by Julius Malema. “I was very angry with her,” Dlamini said. “I told her ‘the ANC is the one taking you to school!’”

Hers is not the only family falling out over politics. Mary Monyweka, a 58-year-old ANC official in Tshwane, has had similar rows with her daughter. “It feels so painful,” she said.

Supporters hold a figurine of Nelson Mandela during the ANC rally in Soweto. Photograph: Madelene Cronjé

Monyweka pulled up her trousers to show a bullet wound she received in the Soweto uprising in the summer of 1976. “She doesn’t understand what is going on, she doesn’t understand,” she said.

Monyweka doesn’t know who her daughter will vote for. “It’s a secret,” she laughs. Aside from the EFF, the party of Mandela is also likely to lose votes to a new party formed by Zuma, uMkhonto we Sizwe, which takes its name and logo from the ANC’s former paramilitary wing.

There is no shortage of other options, with 52 parties on the ballot, the most popular of which aside from the ANC is the Democratic Alliance (DA), which has gained a reputation for its relatively impressive management of Cape Town and Western Cape province.

At a DA rally at a much smaller venue in Soweto last Wednesday, a far younger crowd had gathered. There was anger at the ANC and none of the residual loyalty felt by older black South Africans. “Our children drink dirty water and go to sleep hungry,” said 36-year-old April Molobi who had come along with his twin sister, Paulina, and nephew Thalepo. “I just want the government to give us jobs so we can work. Nothing more, nothing less.”

DA supporters attend a rally held by the party at the Soweto Theatre in Soweto. Photograph: Madelene Cronjé

Paulina described waking up at 3am to unsuccessfully queue for jobs. Thalepo recounted the various qualifications he’d received at school. “I have plenty of certificates but they are not working for me,” the 28-year-old said. He left school eight years ago and has been unemployed since. If he had his choice of job he would be a private investigator, he said, as he told tales of corrupt officials and dodgy politicians.

But the DA is still hamstrung by the sense that it is a party dominated by white people. The crowd at last week’s rally was almost entirely black, but backstage where the party’s staff and politicians mingled, the proportion of white people was far higher.

Back at the ANC rally, past the stalls selling hats, shirts and T-shirts in the party’s yellow, green and black, many of them emblazoned with the faces of long-dead liberation heroes, stood Stephen Serapezo, a 62-year-old housing official in Johannesburg who was waiting for friends to arrive.

Members of uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the paramilitary wing of the African National Congress. Photograph: Madelene Cronjé

He accepted that the ANC “wronged the people” when Zuma was in charge.

But the ANC is renewing itself, he insisted: “All the rotten apples have left the movement.” And he cited the government’s stance on Gaza, particularly its decision to take Israel to the international court of justice. “We are leading the world in making sure that Palestinians have a voice internationally.”

If the ANC needs to go into coalition, Serapezo would favour a deal with the DA, which he believes has similar economic policies. But he accepts that is a minority view at this rally. “They wouldn’t accept it,” he says, waving his hands at the crowd. “They see it as a white party, full stop, not ‘do we have anything in common?’”

Regardless of the thinning crowd, Serapeza believed his party and country had a brighter future. “We’re getting somewhere and there’s hope. There is no reason to be despondent.”

Steve Bloomfield is head of news at the Observer. He is also the author of "Africa United: How Football Explains Africa" (Canongate)

Guardian US is renowned for the Paradise Papers investigation and other award-winning work including, the NSA revelations, Panama Papers and The Counted investigations. Donate to The Guardian: Support fearless, independent journalism. We're not owned by a billionaire or shareholders - our readers support us. Choose to join The Guardian with one of these options. Cancel anytime.

************************************

Apartheid’s Long Shadow Hangs Over South Africa’s Election

By Ntando Thukwana, S’thembile Cele, Mpho Hlakudi, Tom Fevrier, Kyle Kim

for Bloomberg CityLab

May 25, 2024

https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2024-south-africa-election-racial-in…

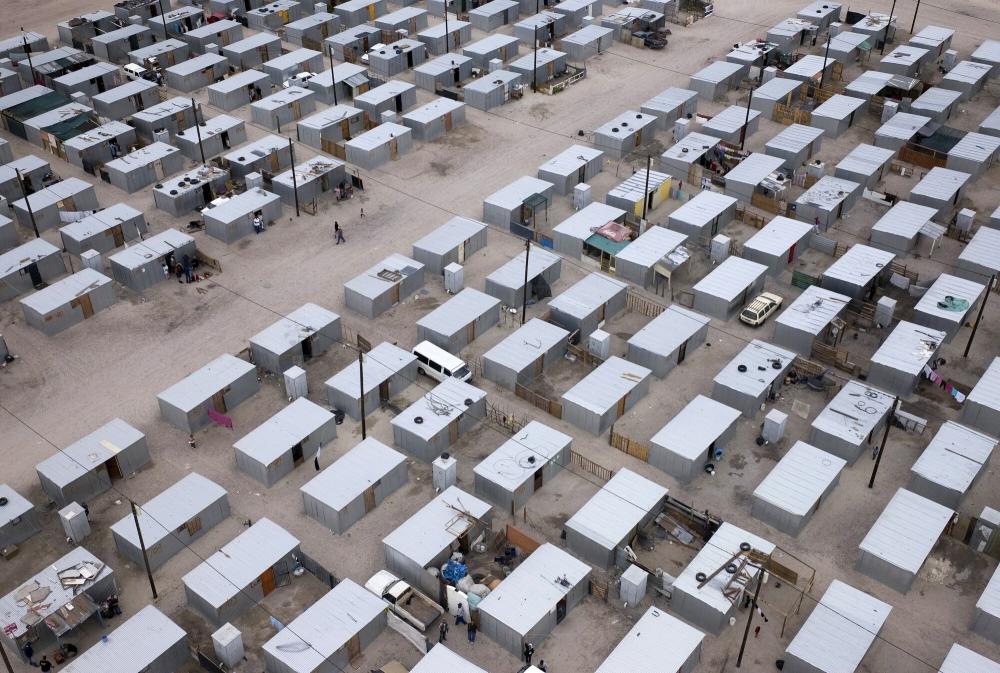

An informal trader’s stall in the Slovo Park settlement outside Johannesburg in May. Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

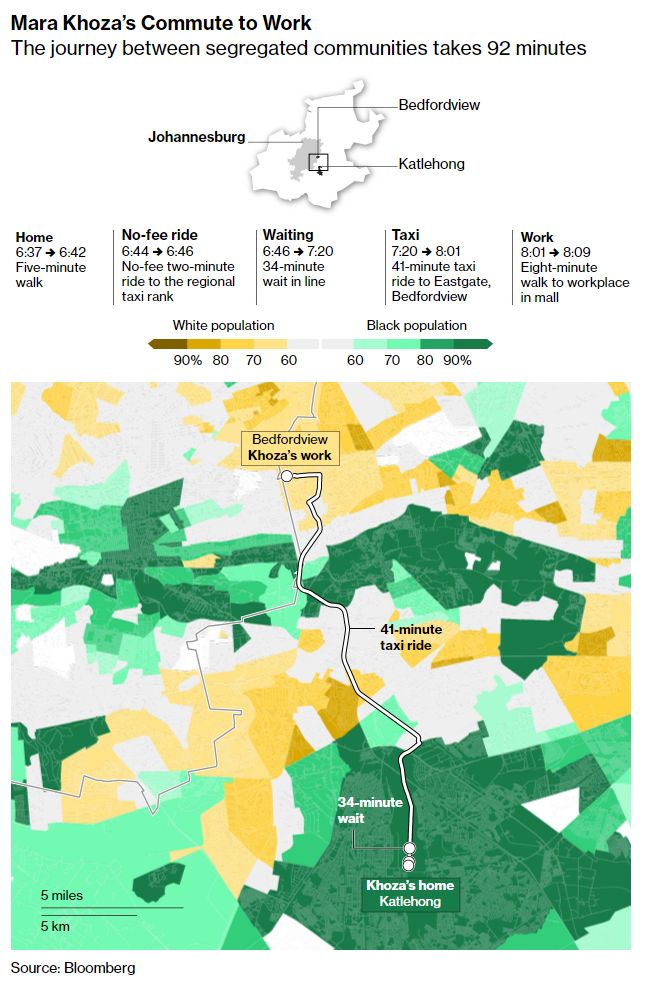

It’s 5 a.m., just after the crack of dawn, and a heavily pregnant Mara Khoza is already on her feet, mustering the strength for a grueling commute to work.

As she steps out the door and begins her trek to the taxi stand, the 38-year-old is met with thick morning smog intermingled with the smoke of burning coal. She makes her way through streams of people traveling to the city, hawkers, and children in school uniforms hopping over puddles and taking pains to avoid the open sewage that runs through the streets.

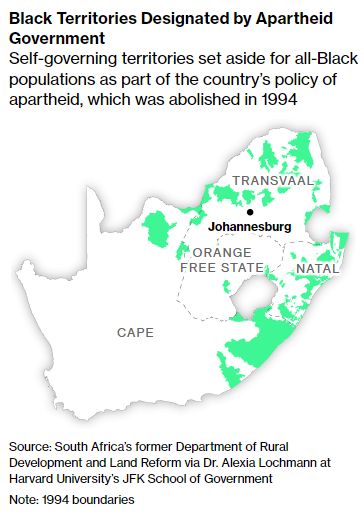

Khoza lives 29 miles outside of Africa’s richest city, Johannesburg, in Katlehong, South Africa’s third-largest township. The area’s name means “place of success,” and it’s one of the hundreds of residential areas that served as dormitory towns under apartheid for Black people working in nearby cities. Since then, it has grown to a population of more than 407,000, almost all of whom are Black. Just over a quarter of residents, including Khoza, live in corrugated iron sheet homes without access to electricity. The rest, in the more formalized parts of the township, live in the four-room brick houses that were provided to Black families during White rule.

Mara Khoza at her home in Katlehong, outside Johannesburg. Khoza commutes 40 kilometers every day to her job at the Eastgate Mall in an affluent suburb.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Like countless other South Africans, Khoza waited for years to receive a new home under a state-led program, only to be allocated a piece of vacant land when her turn finally arrived. Workers erected toilets, and said they’d come back at a later stage to build houses. They never did, and while Khoza is grateful for the plot, she also feels abandoned by the government.

“They need to clean up this place and help people who are struggling,” Khoza says of the vacant grassland near her home and the ruling African National Congress party, whose colors she still displays in her window. “Because in this place, people get raped. People get killed, all these nasty things happen here – there is no progress happening.” Now, with elections coming up on May 29, the party that has governed continuously since the end of apartheid stands to lose its majority because of places like Katlehong, where Black residents live with the consequences of the ANC’s broken promises.

When the party ascended to power under Nelson Mandela in 1994, it ran on the slogan “a better life for all,” promising to undo the damage of 46 years of apartheid by expanding access to housing, healthcare, education, and economic uplift. Yet three decades on, South Africa remains starkly divided along racial lines. The country’s unemployment rate ranks among the highest globally, with joblessness among Black people exceeding 36% — compared to less than 10% for the country’s White population. Nearly two-thirds of residents live in poverty, most of them Black. According to the World Bank, a tenth of South Africans, the vast majority of them White, own 80% of all wealth, making it the most unequal nation in the world.

The failure to fully address the legacy of apartheid – which determined not only where people could live, work and travel, but also who they could marry, how they could be educated and whether they would be condemned to poverty – still affects every facet of life in South Africa. It dictates access to schools and healthcare, distance to work and amenities, the impact of violent crime and corruption, and ultimately means that White South Africans are far better off than the Black majority. Beyond basic necessities, residents in White suburbs enjoy parks, recreational facilities and creature comforts that are “a far reach” for Khoza and her neighbors. “Everything is there,” she says.

People line up on a chilly May morning to wait at a taxi stand in Katlehong, a hub of activity during the week. With a population now in the hundreds of thousands, Katlehong is believed to have been set up as a residential area for migrant workers looking for employment in the surrounding mines.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Commuters jam into a taxi in the Katlehong township. Local taxis — informal mini-buses that often cost riders around a third of their wages — stand in for the lack of public transportation. Many poor South Africans spend up to an hour each way traveling from townships to school or their places of work.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

The Katlehong taxi passes through several suburban areas around Johannesburg before reaching the wealthy enclave of Bedfordview. Many commuters from townships and informal settlements must take multiple taxis to get to their destinations.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Commuters then walk the final leg of their journey. It’s a scene that recalls the apartheid era, when restrictions on movement forced Black workers to make expensive and onerous daily commutes, including by foot.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Bedfordview, an affluent suburb with big houses, high walls, and high-end retail stores, was founded by White settlers in the 19th century.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

South Africa’s racialized wealth divide comes into sharp relief in Bedfordview, an affluent Johannesburg suburb where Khoza works for the online division of a clothing store, commuting more than 90 minutes each way. With its high-rise buildings, perfectly manicured lawns and robust transit connections, the town is home to a lively business district that features brand-name retailers including H&M and Zara, Starbucks and Birkenstock. More than 70% of its majority-White population live in mansions enclosed by high walls. Here, power and water outages – increasingly frequent as the country’s infrastructure has deteriorated – are typically announced or fixed within hours of being reported.

Before the official end of apartheid in 1994, Black people were only allowed to work in areas like Bedfordview and were forced to live in informal settlements. Even townships “were not integrated towns with facilities, shopping, medical facilities — none of those kinds of things,” says Neil Klug, a senior lecturer at the University of Witwatersrand’s School of Architecture and Planning. Rather, they were developed according to the so-called 40-40-40 rule: built 40 kilometers from city centers, homes were 40 square meters, and Black residents were expected to spend 40 percent of their income on commuting to work. “Just rows and rows of these little houses, which people find fairly dehumanizing to live in,” he said.

“These townships were very carefully designed,” Klug noted. They “had very limited access points going in and out of the areas for security reasons, to enable the apartheid security forces to block them off very easily to control any form of social unrest.”

A man rides a horse on scrubland overlooking the Soweto township on the outskirts of Johannesburg, circa 1965 Photographer: Paul Popper/Popperfoto/Getty Images

The High Court Building on the corners of Pritchard and Eloff streets in the center of Johannesburg in 1966. Under apartheid, this district was only accessible to Whites. Photographer: Paul Popper/Popperfoto/Getty Images

Families being removed from their homes in Johannesburg in 1955, that year residents were also forced from the Black cultural hub of Sophiatown to create a Whites-only suburb. Photographer: Terence Spencer/Popperfoto/Getty Images

Children climb through a barbed-wire fence separating a Black residential district from a White one, in 1963. Source: Jacoby/ullstein bild/Getty Images

An aerial view of Soweto a decade after protests broke out following the apartheid government’s decision to force schools to teach in Afrikaans, in 1986. Photographer: William Campbell/The Chronicle Collection/Getty Images

Workers walk home in New Brighton, Eastern Cape, in 1985. Photographer: William Campbell/The Chronicle Collection/Getty Images

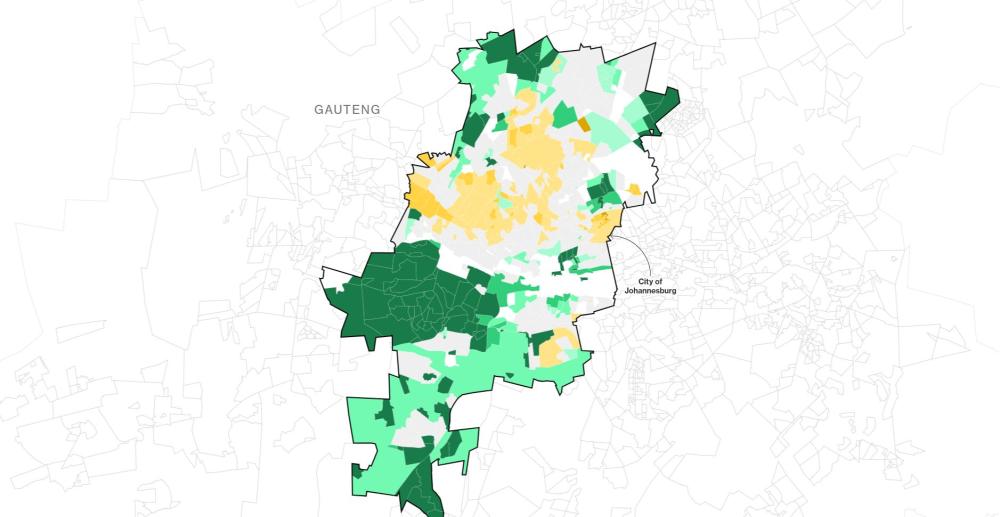

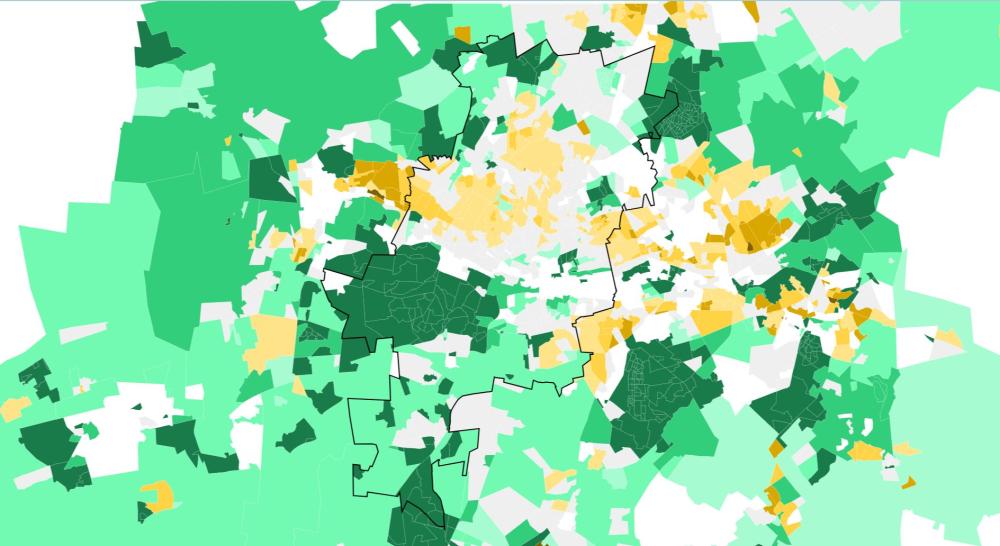

Decades later, these same patterns of segregation are still present in Johannesburg and the surrounding suburbs.

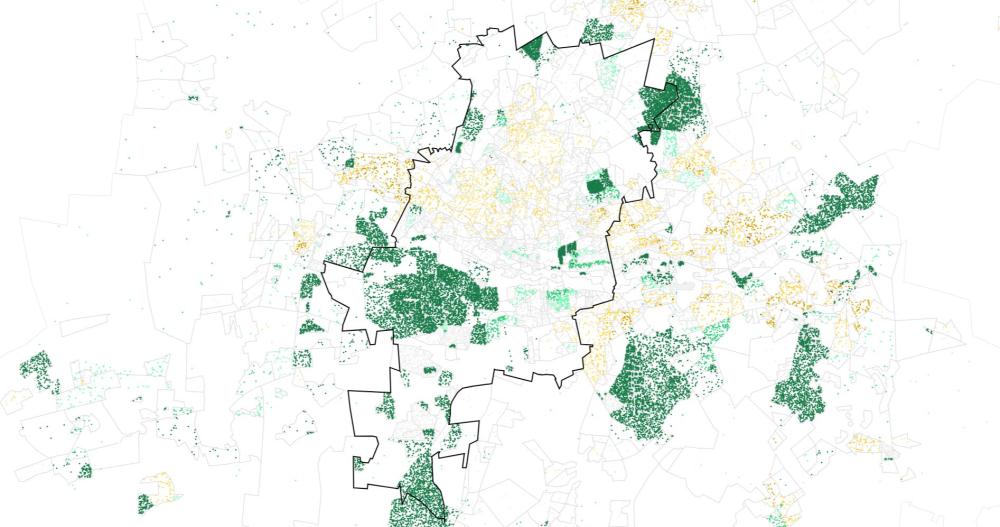

A Bloomberg News analysis of 2011 census, the most recent detailed demographic data available, shows that nearly three-quarters of the neighborhoods in Johannesburg’s Gauteng Province have a single racial majority of at least 60%.

Predominantly White neighborhoods are clustered within the city center, close to businesses and services. Black-majority neighborhoods fan out from the center — 44% of those neighborhoods have a Black population of 90% or more.

Spatial patterns of segregation continue in the suburbs and townships in the rest of the Gauteng region surrounding the city. Of those neighborhoods, 29% are majority White, 47% majority Black neighborhoods. Additionally, 15 of the region’s 1,795 racial-majority neighborhoods are mixed-raced majority and 17 are Indian/Asian majority.

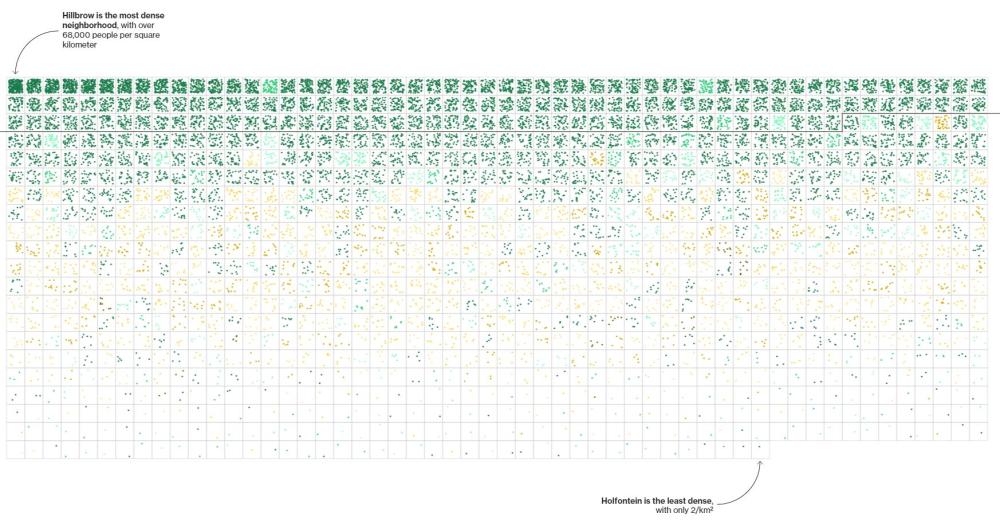

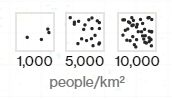

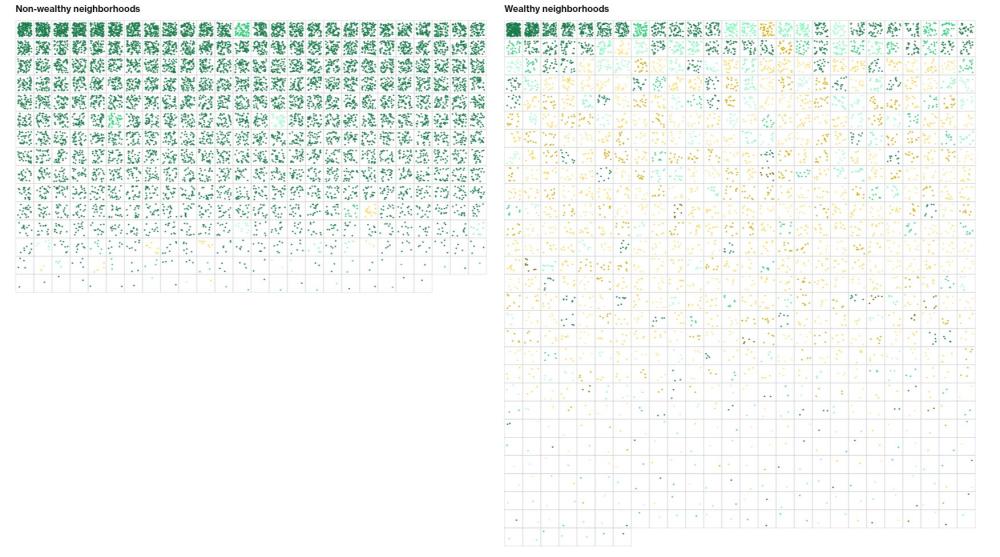

The lasting impact of apartheid-era segregation can be seen in the high population density of majority Black areas.

Each dot represents 250 people.

Nearly all of the most densely populated neighborhoods — those with over 10,000 people per square kilometer (25,900/sq mi) — are majority Black. None are majority white.

Life is infinitely better for South Africans now than it was during apartheid – basic human rights are guaranteed to all citizens, access to education has improved substantially, a Black middle class has taken root. South Africa enjoys per capita GDP three times that of Nigeria or Kenya. Crime and corruption are rife, but few would return to life under a government that terrorized and subjugated the vast majority of its citizens. “One of the big promises that the new governing party made when it came into power was this idea that you will have access to opportunities,” said Kneo Mokgopa, a writer and former researcher at the Mandela Foundation. “At the very least on paper,” they say, that “has been upheld.”

Yet systemic graft has stalled efforts to create a more equitable society, disillusioning many Black voters who were once ANC loyalists. Public systems have broken down under the weight of financial mismanagement and a lack of good governance, with years of underinvestment eroding things further. This peaked in the 2010s under former president Jacob Zuma, whose tenure was characterized by the plunder of state institutions. Zuma has denied all wrongdoing, but according to a 2018 inquiry, the amount of public money “tainted” by corruption during his nine years in office was around $27 billion, with the country’s national rail, port and pipeline company, and the state-owned power company, most profoundly affected.

Now, ahead of its toughest-ever election, the ruling party is facing a moment of reckoning. More than 50 parties are vying to oust the ANC, including one launched by former president Zuma on the eve of the election. While none are expected to secure a majority, polls suggest that the ANC will dip below 50% for the first time, making a coalition government likely.

When the ANC took power in 1994, as many as seven million South Africans were either homeless or living in informal settlements. Expanding access to adequate housing became a core part of the party’s platform, and was even enshrined as a right in the country’s new constitution.

In its first five years in office, the ANC pledged to build one million subsidized houses, redistribute land to the landless and electrify 2.5 million homes as part of a sweeping framework called the Reconstruction and Development Program. Its first initiative, dedicated to providing South Africans with fully built homes, lasted nearly a decade and resulted in about 1.1 million houses before it was gradually phased out. The government then spent more than three years parceling out vacant plots, such as the one Khoza received.

President Cyril Ramaphosa counts housing as one of the ANC’s greatest achievements, boasting that the party has provided South Africans with 4.7 million “housing opportunities” – which can include a plot of land, a rental home or subsidy, or an actual house. Still, demand far outstrips supply. More than 2.4 million households are awaiting assistance, and among the houses that have been built, many were constructed poorly and without promised amenities like electricity or running water. But the government’s approach – restricted by the fact that cheap land was most often available outside of cities – also entrenched inequality.

“The government tended to purchase agricultural land on the periphery of the city,” Klug said of the early ANC years. “You could simply convert it into urban land and roll out thousands of houses, which is what they did. Unfortunately, what that did, in a sense, was consolidate that apartheid spatial structure.”

A worker stands on the roof of a RDP (“Rapid Development Program”) house, also known as a “Mandela house,” in Soweto, in February 2004. Photographer: Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images

Subsidized housing built by the local government in the township of Delft outside Cape Town, in March 2009. Photographer: Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images

African National Congress (ANC) President Nelson Mandela arrives at a rally in Katlehong in August 1993, eight months before South Africa’s first universal election. Source: Philip Littleton/ AFP/Getty Images

Construction workers build homes for a new low-cost housing project in Johannesburg’s Alexandra township, in April 1999. Photographer: Odd Anderson/AFP/Getty Images

A woman tries to stop a bulldozer from destroying her house in Lenesia, southwest of Johannesburg, in November 2012. Earlier that day, protests erupted after the government demolished 37 homes. Source: AFP/Getty Images

Residents clash with police during a protest for better housing in May 2017, in Ennerdale, south of Johannesburg. The area is mostly made up of informal settlements. Photographer: Gianluigi Guercia/AFP/Getty Images

With around five million people still living in the country’s roughly 3,600 informal settlements, the recent focus has been on widening access to basic services. In 2019, the government launched a grant program to provide people with brick-and-mortar homes equipped with running water, electricity, sanitation services and stormwater drainage. The aim is to eventually upgrade 1,500 settlements. So far, 197 have been completed.

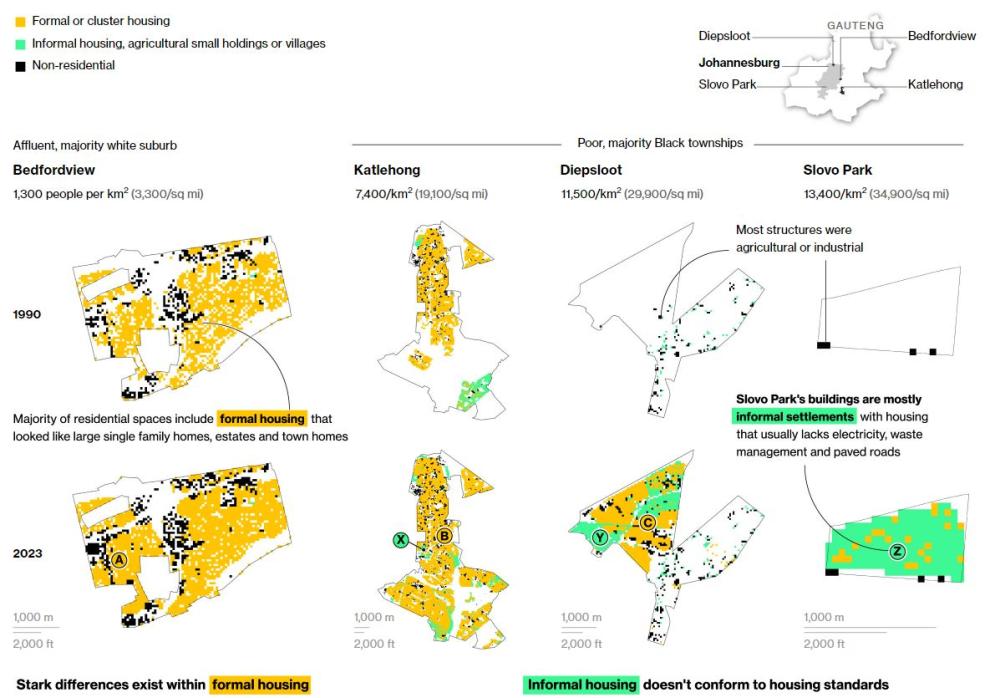

Townships Expand Housing But Lack Services

By 1990, Bedfordview was already an affluent suburb with commercial spaces, schools, health-care facilities and other types of valuable infrastructure. Across Johannesburg, many poor and predominantly Black neighborhoods still lack adequate services.

North of Pretoria, inhabitants of an informal settlement called Koppewaai are among the beneficiaries of this program, which has built 255 houses in the area in the past four years. While residents appreciate no longer hearing rain drum loudly on their iron sheet roofs, they’re also frustrated by how much is still to be done.

“It’s all just the same,” says Frans Baloyi, an elderly man who received his first home in 2019. In lieu of electricity, Baloyi cooks with paraffin and gas. There is no infrastructure for sanitation, and he accesses running water via a neighbor’s pipe that he extended into his yard. “Yes, I have a toilet,” he says, “but it’s not working.”

Frans Baloyi, now in his 70s, stands in his first-ever home, which was provided by the government in 2019 under a grant to upgrade South Africa’s informal settlements. Photographer: Cebesile Mbonani/Bloomberg

Basikopo Makamu, a member of the province’s executive council, manages and oversees municipal services. He acknowledges that building bulk infrastructure, addressing a housing backlog and finding land to develop are challenges, but points out that initiatives like the upgrade program are key to unlocking development in informal areas. Nicer homes attract commercial outlets, which in turn create jobs.

Whether that proves true in Koppewaai remains to be seen, but Makamu notes that the very existence of such programs is unique to South Africa. “Nowhere else will citizens be given a serviced site, a house, at the government’s expense as part of basic services,” he says.

“Our constitution is very expensive.”

Thirty miles from central Johannesburg, street corners bustle with hawkers, makeshift homes crowd cramped plots of land, and children fill the streets. Diepsloot has mushroomed in size since it was established in 1995 as a temporary dwelling for people evicted from informal settlements, and as of 2011 it was home to more than 138,000 residents.

At a busy crossroads, Tshepo Manabile hangs posters for the newly formed uMkhonto weSizwe party featuring its leader, ex-president Zuma. While Manabile was once an ANC supporter, he now believes the party is broken beyond repair. “We hate what they have done and the hurt they have caused the people of this country,” he says. “We feel that as Black people we did not get full freedom. The freedom we have, I would say, is the right to vote, but in other areas life is getting tougher every day.”

Among the challenges poorer South Africans face is accessing health care. Despite being one of South Africa’s most populous townships, Diepsloot has only two clinics and the closest hospital is more than six miles away.

While his wife prepares cornmeal over a paraffin stove, Joseph Ledwaba sits on the porch of his brick house. Now in his old age and suffering from chronic illness, Ledwaba has nevertheless given up on the public health care system.

“Really, I no longer go to the clinic,” Ledwaba said, describing how he would sometimes arrive as early as 4 a.m. just to stand in line for care. “You’ll get there and wait and get dizzy.”

The ANC introduced free health care in 1994. Three decades on, South Africa’s system ranks among the continent’s best, but that’s largely due to the strength of the private sector, which serves just a sliver of the population. More than 86% of South Africans, many without insurance, instead use the strained public health services, which are mostly concentrated in townships and informal settlements.

By March 2022, 3,612 units had been built in the Riverside View township to relieve housing pressure in overcrowded Diepsloot. The project aims to yield over 10,000 houses.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Diepsloot, located about 30 miles from downtown Johannesburg, has mushroomed in size since it was established in 1995 as a temporary site for people evicted from informal settlements. The township has been struggling with increasing crime and violence in recent years, as residents say the authorities have left them to fend for themselves.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Established in 1995 as a temporary dwelling for people who had been evicted from nearby informal settlements, Diepsloot has grown into one of South Africa’s most populous townships, with more than 350,000 inhabitants. The area, whose name is the Afrikaans word for “deep ditch,” suffers from high levels of unemployment.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

ANC politicians “don’t step foot in squatter camps,” says Lady Bee, a community organizer in Diepsloot. “But when it’s time to vote, they come back here and tell us lies. So, what do we end up doing? We end up realizing we’re powerless and give up, you understand. They’re all the same — there is nothing they do for us.”

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Although the number of Black and female medical students has jumped since 2000, population growth means there’s far more demand for trained medical personnel than there are available doctors and nurses. With public hospitals overburdened, understaffed and underfunded, nearly 80% of all doctors work in the private sector.

In mid-May, President Ramaphosa signed into law an ambitious attempt to dismantle this two-tiered approach. The National Health Insurance Bill aims to address “apartheid in healthcare” by essentially doing away with most components of private medical care in favor of creating a single system for all.

On what was once an abandoned farm outside Johannesburg, children kick a beat-up soccer ball through a patch of dusty gravel. Music and the voices of TV announcers drift from the tin shacks that line Slovo Park’s unpaved roads. Named after ANC stalwart Joe Slovo, the democratic government’s first minister of housing, this informal settlement was established the year before the country’s democracy. After the end of apartheid, its population swelled as people migrated to live closer to the city.

The little development Slovo Park has seen has been hard won. Despite securing a court judgement against the City of Johannesburg in 2016 that ordered it to spend millions on formal housing in the settlement, not much has changed. The government has provided access to electricity, but not everyone has running water, and a promised community upgrade never took place. Slovo Park’s few brick-and-mortar structures were built by residents. Fencing is made up of old burlap sacks, corrugated iron and plywood boards strung together with wire. Power lines hang dangerously low.

Named after ANC stalwart Joe Slovo, the first Minister of Housing in the democratic government, Slovo Park was established in 1993 when a farmer abandoned his property and people who worked in nearby industrial areas began dividing and occupying it amongst themselves.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Nearly a decade since a court ordered the government to build formal housing in Slovo Park, residents are still waiting on that promise to be fulfilled. The state has provided the settlement with electricity, but only a fraction of households can access it.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Slovo Park residents attend a meeting at the Slovo Community Hall to discuss issues affecting their quality of life. Thirty years after the end of apartheid, residents are still urging the government to replace pit latrines in the area with working toilets.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

As the government has failed to make good on its promises, protests have become increasingly common in Slovo Park. People took to the streets two years ago after electricity company employees began cutting illegal power connections, and in 2023, residents repeatedly blocked a ring road around Johannesburg in response to the lack of running water and power.

Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Just months ago, angry residents burned tires on the streets, shutting down a highway, to get the government’s attention. There are no schools in Slovo Park. To receive an education, children must cross a bridge into a nearby community or travel miles to neighboring townships. Since the end of minority rule, the percentage of Black South Africans attending school has steadily risen to 74%, fulfilling an ANC pledge to widen access. That improvement, however, masks stark inequalities. South Africa has “one of the most unequal school systems in the world,” according to a report byAmnesty International, “with the widest gap between the test scores of the top 20% of schools” — which most White students attend — and the rest. Overcrowding, shoddy infrastructure, poor sanitation, underfunding and difficulties recruiting and retaining qualified teachers weigh on the system. A 2021 study of fourth graders’ reading abilities ranked South Africa last among 57 countries, with 81% of students unable to read for meaning. These challenges are reflected in universities and trade schools, as only seven percent of South African adults — among the lowest rates in the world — have received tertiary education, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Twenty-five-year-old Lerato Molete is among the other 93%. “Born free” five years after the country declared its democracy, Molete walks the streets of Slovo Park on a Monday afternoon with nowhere to be. She was raised in the informal settlement by her late mother and grandmother.

“My mom was a domestic worker in Fourways; it is extremely far. I remember she would leave very early, by 4 a.m. she would be gone,” Molete recalls. She attended school in a nearby community, but was eventually unable to afford her studies.

Molete now works as an administrator for a construction company, leaving the house around 6:30 a.m. Her biggest frustration is her low pay, which she stretches to support her uncle and grandmother. “I just want a good job,” Molete says. “I don’t know where or doing what exactly, but I just want the basics, the good things that other people have. I want benefits like medical aid, I want stability on a long-term basis, I want things of my own.”

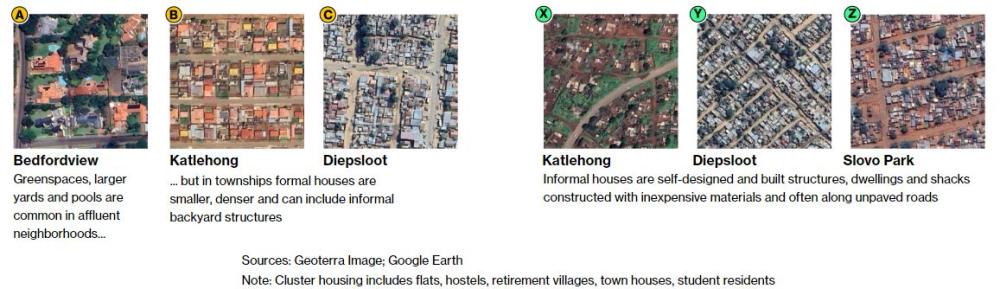

Lerato Molete in the two-room metal sheet home in Slovo Park that she shares with her uncle. Photographer: Leon Sadiki/Bloomberg

Unlike those who witnessed the birth of a democratic state only to see its dream of egalitarianism unravel, the nearly half of South Africans born after apartheid have also been disillusioned. Apartheid is over, yet extreme inequality and poverty persist. Economic uplift remains distant to many. Frustrated by years of unfulfilled promises, those who lived under minority rule and those raised in its aftermath may soon move the country in a different direction.

“They gave us political freedom, but we don’t sleep at night,” says Lady Bee, a 40-year-old community leader from Diepsloot. “What do criminals have? They have freedom – the freedom to go around killing people. So which freedom exactly can you point to except for criminality?”

“The government has failed us, not once, but so many times,” she added. “I’m disappointed in such a way that I could wake Mandela up and say: do you see what you have left us with? Can you see your people?”

With assistance from Jeremy Scott DiamondHayley WarrenEdited by Jessica LoudisNeil MunshiMichael OvaskaMaria WoodJody MegsonMonique Vanek

Methodology

Geographies

Neighborhoods were derived from subplaces, the second lowest level of administrative boundaries in South Africa’s census. Some of the 2,579 subplaces in the Gauteng Province were combined based on name and location — when subplace names refer to the same neighborhood and corresponding extensions, and for some of the smallest subplaces. For some neighborhoods, the main place, or the third lowest subdivision was used instead. In total, 784 subplaces were merged with other subplaces resulting in 1,795 neighborhoods.

Data

The 2011 census data by race is the most recent demographics available at the main place, subplace and small-area level, the lowest type of administrative boundary. Small area racial demographics were aggregated at the aggregated neighborhood level. Population density was calculated using the total area of each neighborhood and the aggregated population.

Each neighorhood’s binary classification of wealthy and non-wealthy was calculated with the largest overlap of our neighborhood boundaries and the boundaries from the Dair Institute’s spatial analysis of wealthy and non-wealthy settlements.

Non-residential, unpopulated or sparsely populated neighborhoods (less than one person per square kilometer) were omitted from our analysis. Neighborhoods without a majority race of 60% or more were not included. Neighborhoods with other majority races — mixed raced or Indian/Asian which account for about 3% of all residential neighborhoods — were also excluded from our analysis.

A letter from the Editor-in-Chief, Bloomberg

Thank you for taking a look at what we do.

Every day, Bloomberg’s 2,700 journalists and analysts break news all the way around the world. But we also try to explain that world in all its complexities, so that you get the bigger picture. We cover more companies, industries and markets in more depth than anybody else, and we are always looking for the links between them.

As they say, context changes everything.

John Micklethwait

Editor-in-Chief

Bloomberg