Why Has Trump Stopped Attacking Big Business?

"Who wants open borders? Who wants men playing in women’s sports? Who wants all electric cars?" - Donald Trump, this week at a Nevada rally

This week, Donald Trump met with the Business Roundtable, which is the most important business lobby in America. Composed of roughly 200 CEOs of top corporations and private equity funds, many of whom are in the crosshairs of antitrust, the Business Roundtable is a key organizing forum for Presidential candidates.

I pay close attention to the current administration, because I write about the legal and policy choices of the government. But an election is coming. And given the Business Roundtable meeting, I decided to spend some time on Trump. He’s a hard figure to analyze, because little of the news coverage is about policy. Moreover, there’s almost no awareness of what his government did while in office.

So to look at Trump, I decided to listen to three recent speeches, and compare them to what he said in 2016 and what he did on antitrust and trade while in office.

What I found was surprising. In 2016, he feuded incessantly with corporate America, telling a story about big business as part of the corrupt establishment trying to outsource jobs and replace American workers with cheap labor. His post-Presidential years have seen a different figure. He just doesn’t talk about corporate America very much anymore. Something has changed, and I’m going to try and identify that change and understand its significance.

Donald Trump vs the Establishment

One of the more powerful political ads I’ve seen is the one then-candidate Trump put up as his closing case in 2016. It was a two minute long economic populist story, linking shuttered factories with Wall Street, the Federal Reserve, Hillary Clinton, and big business. “It’s a global power structure,” Trump narrated over the image of a shuttered factory, “that is responsible for the economic decisions that have robbed our working class, stripped our country of its wealth, and put that money into the pockets of a handful of large corporations and political entities.”

The imagery was striking, from empty factories to Bill Clinton lobbying for NAFTA to Barack Obama lobbying for the successor agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The ad had anti-immigrant arguments, but they were linked to trade deals and a corrupt foreign policy. It was a compelling pitch for swing voters in the midwest.

At the time, Democrats seemed uniquely fat and happy. In the summer of 2016, a manufacturing worker from the corporation Carrier, which had just announced it was sending jobs to Mexico, asked President Obama at a town hall meeting about offshoring. Obama was annoyed. Such jobs, he said “are just not going to come back.” Trump’s appeal in that context was pretty obvious.

More broadly, for decades, big business leaders had been sacrosanct in American politics. But Trump openly feuded with them. For instance, Trump picked a fight with Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, one of the richest men in the world. "Amazon is getting away with murder tax-wise,” Trump said. “He's using the Washington Post for power so that the politicians in Washington don't tax Amazon like they should be taxed."

Bezos didn’t like Trump, he said, because "he thinks I would go after him for antitrust because he's got a huge antitrust problem... What he's got is a monopoly and he wants to make sure I don't get in." The idea that ownership of a newspaper would mean that owner meddled in coverage was just not said in polite company. But Trump said it.

Trump didn’t just slam Amazon. In October of 2016, AT&T announced it would buy Time Warner. Trump blasted the deal, saying that “It’s too much power in the hands of too few.” He attacked it in multiple speeches before Bernie Sanders got a press release out. Trump then said he’d break up Comcast’s 2011 acquisition of NBC, saying it "concentrates far too much power in one massive entity that is trying to tell the voters what to think and what to do."

There was a lot more. Trump also called for a boycott of Apple products, and attacked Carrier, Nabisco, Lockheed Martin, Toyota, Nordstrom, and Ford. “To think that Ford is moving its small car division is a disgrace,” he said after the corporation announced it was moving production to Mexico. “It's disgraceful. It's disgraceful that our politicians allow them get away with it. It really is.”

Critics thought it was pure opportunism, but Trump had been a populist on trade since the 1980s, and he always had a chip on his shoulder. ”Big business, elite media and major donors,” he said in his RNC acceptance speech, “are lining up behind the campaign of my opponent because they know she will keep our rigged system in place."

Trump didn’t stop when he won, attacking Rexnord for continuing its plans to offshore. And in 2017, after Merck CEO Ken Frazier resigned from a Presidential council, Trump let him have it. “Now that Ken Frazier of Merck Pharma has resigned from President's Manufacturing Council,” he tweeted, “he will have more time to LOWER RIPOFF DRUG PRICES!” Trump was so hostile to big business that the Wall Street Journal set up a Trump target index to track the stocks that earned his ire.

Anti-Monopoly vs Pro-Monopoly Trump

So what did Trump actually do while in office? There was of course a huge corporate tax cut, which didn’t do much for investment but did spur more buybacks. He held to many orthodox GOP views on taxes, regulations, pollution controls, and so forth. For instance, he refused to ground the Boeing fleet even after the second 737 Max crash, until everyone else in the world had. In certain parts of competition policy, however, Trump broke with the monopoly-friendly status quo. His approach was usually incoherent, but that was a huge step forward compared to what had come before.

Take trade. Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, renegotiated NAFTA, and raised tariffs on Chinese imports. The press pretended that this stuff was mostly fake, but it wasn’t. For instance, the Trump administration blocked imports of lumber from a Peruvian exporter based on concerns over illegal harvesting, the first use of environmental standards in trade law ever by the U.S. government. As another example, there’s now a wave of Mexican labor organizing spurred by the labor provision in the new NAFTA.

The goal for Trump’s trade chief Robert Lighthizer was not to promote the environment, but to make it more expensive to import things. And of course, these weren’t strictly Trump accomplishments, as it was Democrats in Congress working with the Trump administration on new trade arrangements. But the change was stark.

This change in direction, of course, didn’t mean he ‘succeeded’ or honored what he said he would. Trump promised to shrink the trade deficit, but didn’t. The trade deficit with China and Mexico kept increasing on his watch. He also went back on his campaign pledge to deem China a currency manipulator, and he didn’t end government contracts for corporations that outsourced jobs.

In the antitrust realm, the story is a bit more that Trump picked up on the anti-monopoly movement and used it for his own ends. For instance, Trump followed through on his campaign promise by bringing a merger challenge against the AT&T-Time Warner merger, though a judge ruled against him. He didn’t act on Amazon’s monopoly, but he did bring monopolization cases against Google and Facebook, the first cases against big tech in two decades. The administration also blocked Facebook’s attempted launch of its own currency Libra, and ended Amazon’s giant cloud contract with the Pentagon. Trump even promulgated rules against pharmacy benefit managers, and forced hospitals to reveal their price list publicly.

Yet, consolidation worsened, as most mergers went through unimpeded, from CVS-Aetna in health care to Disney-Fox in streaming to the Linde-Praxair industrial gas merger to the Northrop-Orbital merger that placed one corporation in charge of our nuclear arsenal. Trump Antitrust chief Makan Delrahim actually lobbied for the Sprint-T-Mobile deal, which has raised cell phone costs. Trump eliminated the antitrust agency for farmers, as seed and chemicals moved from the Big Six (Monsanto, Bayer, BASF, Syngenta, Dow and DuPont) to the Big Four (Bayer, Corteva, ChemChina-Syngenta, and BASF). We’re still living with Delrahim’s legacy; the rent-fixing cartel run by RealPage exists in part because the Antitrust Division allowed that company to buy out its competition in rent management software.

Ideologically, Trump’s Antitrust Division promoted private equity, allowed Facebook to get away with a fig leaf settlement on Cambridge Analytica, supported certain no poach agreements, and filed amicus briefs on behalf of Uber’s attempt to stop drivers from organizing. He adopted the deregulatory posture of the Bush era and shut down consumer protection in finance. And Trump himself helped bring U.S. drilling firms together with OPEC to increase oil prices in 2020. Then there are the hundreds of judges he put on the bench, who are often hostile to antitrust enforcement.

Still, much of the conservative realignment drew inspiration from Trump’s willingness to buck the corporatist framework, and use government power to structure global and domestic markets. Political leaders like J.D. Vance, Josh Hawley, and Matt Gaetz adopted it eagerly. In 2022, roughly 20% of the House Republican members of Congress broke with the corporate establishment and voted for stronger antitrust laws, a package of bills that were backed by the conservative Heritage Foundation.

On trade, Joe Biden’s administration largely continued and expanded Trump’s China tariffs, while adding in industrial policy to accelerate the on-shoring of factories. In terms of competition policy, Biden broke with Trump in important ways. While he continued the Trump monopolization cases against Google and Meta, he also brought a bevy of other cases against everyone from Amazon to Ticketmaster with aggressive enforcers like Jonathan Kanter and Lina Khan, with the Wall Street Journal even attacking Khan as ‘Trumpian’ for her shift at the FTC. The shift against private equity, though, shows Biden as a different and more economically populist actor than Trump.

What Did Republicans Do In the Wilderness?

Covid, Trump’s loss, and January 6th were a bracing shock to the right. Big tech firms had de-platformed conservatives, large corporations were pledging to never donate to Republicans, and the political establishment saw the rejection of Covid vaccines and mandates by conservatives as reflecting what appeared to be an unmanageable governing situation. It appeared to the right that they were facing an unstoppable giant force of corporate America aligned with a progressive government, all of whom were seeking to eliminate their very existence.

There were two ways to respond, both of which involved rallying around Trump. Some, such as Josh Hawley and Matt Gaetz, saw big business as an existential threat, arguing that large firms were simply too powerful to co-exist with an elected government, as Trump had said in 2016 about media conglomerates. Others, like House Judiciary Chair Jim Jordan and House GOP leader Steve Scalise, retreated to what they knew, which was to treat big business as part of the Republican political machine, but needing a little wayward discipline. They sought to reroute Trump’s argument to say that big business was too ‘woke,’ not that it was too big.

In 2021 and 2022, this debate played out in a bitter fight over new antitrust laws for big tech. Jordan worked with Google, Democrats like Zoe Lofgren and Chuck Schumer, and largely prevailed. Today, instead of attacking Wall Street’s collusion with Hillary Clinton, as Trump did in 2016, Jordan is attacking what he calls a “‘climate cartel’ consisting of left-wing activists and major financial institutions that collude to impose radical environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals on American companies.” ESG is downstream from centralization on Wall Street, as no one would care about Blackrock if the firm didn’t own 10% of every major corporation. But breaking up Blackrock isn’t the goal, the goal is to get Blackrock to stop being “woke.”

The “realignment right” still exists, and pushes some regulations and rules over railroads and Wall Street, but it can only exert real power when aligning with the GOP establishment on cultural questions. Its power lies in the future.

Establishment Trump?

In 2024, Trump took a pro-corporate turn. For instance, he asked his supporters to stop boycotting Brazilian-conglomerate owned Budweiser after the beer giant engaged in progressive-friendly marketing tactics. This shift was not a one-off. In office, he had been fiercely anti-China, and even issued an executive order banning TikTok. But earlier this year, after meeting with libertarian “Never Trump” billionaire Jeff Yass, part owner of TikTok, Trump reversed his position. In office, Trump personally hated crypto, preferring the dollar, but after meeting with crypto executives a month ago, has pledged he’ll support the industry.

And what about economic populism? Well, he recently claimed credit for low insulin prices, and some advisors leaked the idea he’d end Federal Reserve independence, though he hasn’t confirmed it. But there isn’t much beyond that. I listened to his three most recent speeches, in the Bronx, Nevada, and Arizona, to understand how he talked about policy. I wanted to know if Trump had truly altered his arguments. Now of course there will be some inherent changes, as time has passed, there’s a much different environment, particularly around inflation, foreign policy, and legal/political elements of the 2020 election. But even so, his argument is now different.

Trump’s 2024 economic frame is about nostalgia for the time he was in office, when he ran “the greatest economy in history” with cheap gas, high wages, low immigration, and cheap money. By contrast, the Democrats, he said, are “a party of misinformation, disinformation, cheating on elections, open borders, high interest rates, and high taxes." Rents are up and incomes are down, he told voters, because of the open border policy and the illegal immigrants brought here by “Crooked Joe."

What’s fascinating is that he does not criticize big business, and doesn’t much talk about jobs going to China or Mexico, though he does talk about tariffs. Instead, Trump has a couple of new themes. First, he argues that the war in Ukraine wouldn’t have happened if he had been in office, and more broadly global leaders like Xi Jinping respected him in a way they don’t respect Biden. (“So, Russia going into Ukraine would’ve never happened. None of this stuff that you see would’ve happened.”) Second, he complains nonstop about electric cars. Third, he is now making arguments about gender questions like trans people playing in sports. Finally, he often talks about drilling for more fossil fuels, tax cuts, and deregulation.

In other words, Trump sounds like he is the coalition leader of the Republican establishment. He’s still funny, and he’s still weird, and still iconoclastic in terms of his personality. But in terms of what he promises, he’s mostly stopped challenging big corporations, except in cultural terms acceptable to Wall Street. At the Business Roundtable and elsewhere, for instance, Trump offered a cut to corporate income taxes and a rollback of rules on corporations, especially the oil industry.

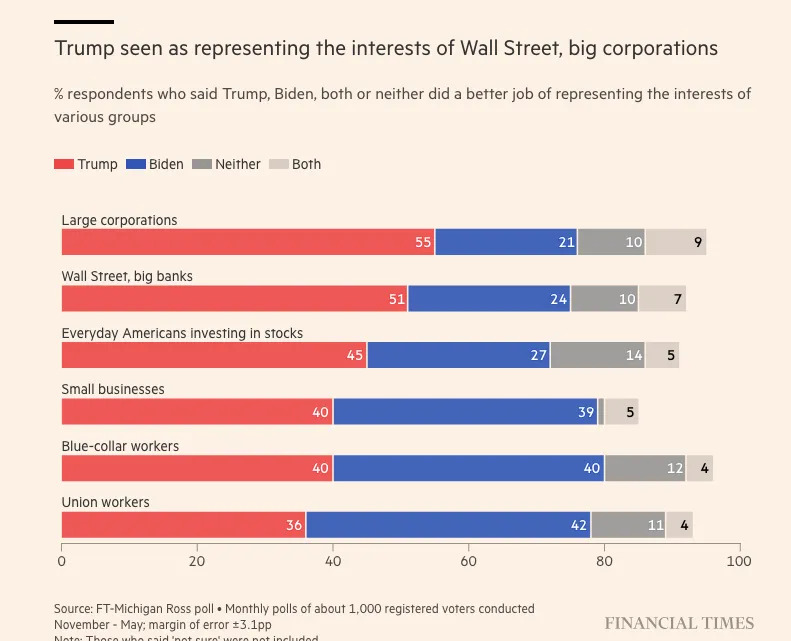

These arguments seem to be working, as he’s leading in the polls. Support for Trump in Silicon Valley and Wall Street is up, with the candidate getting about 50% more in donations from securities and finance than Biden, a stark reversal from 2016. Business lobbyist Kathy Wylde noted that Republican billionaires have told her “the threat to capitalism from the Democrats is more concerning than the threat to democracy from Trump.” And for what it’s worth, the public no longer sees Trump as an economic populist.

Does This Shift Matter

I’ve asked a number of contacts on the right what they think about Trump’s change. Most acknowledge it. “Steve Bannon’s gone” was one observation, and there are grumblings from social conservatives.

Some think Trump is not going to govern as an economic populist if he wins again. Wall Street figured him out, goes this argument, and have used flattery and money to get him onto their side. That said, this view isn’t uniform. The campaign for the Vice Presidency matters, with populists like J.D. Vance in the mix, but also tech titan Doug Burgum, Virginia private equity executive turned governor Glenn Youngkin and Walmart-friendly Senator Tom Cotton.

Trump is, if nothing else, unpredictable. So these new arguments may mean nothing, and he may get right back to attacking big business if he wins. But in 2016, his feuding with corporate America did shift politics. I suspect that his refusal to do so now is something that most political reporters and activists aren’t noticing. But he has a different argument now, and that means a different path to victory, and a different governing regime if he wins.

Thanks for reading! Your tips make this newsletter what it is, so please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or other thoughts. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation, and democracy. Consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy.

cheers,

Matt Stoller