What Is the State of Organized Labor? Whatever Its State, There’s No Basis for “Fortress Unionism.”

Last year was a good year for organized labor. At least that’s the popular perception. And that perception has some real basis. Major strikes, including ones that led to substantial victories for workers, marked a positive surge of the labor movement in 2023—and perhaps on into 2024. (See sidebar, “Some Major Strikes of 2023.”) The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 2023 saw an increase of 139,000 in labor union membership following an increase of 273,000 the year before. What’s more, according to Gallup polling, public approval of unions was higher in 2022 (71%) and 2023 (67%) than it has been since the mid-1960s.

Workers were undoubtedly emboldened by the strong labor market, with unemployment continuing to run at all-time lows—below 4% since the beginning of 2022, and at 3.7% at the end of 2023. For production and nonsupervisory employees on private nonfarm payrolls, average real weekly earnings (i.e., adjusted for inflation) continued their rise of the last few years, up 5% in 2023 from 2018. Yet, 2023 real earnings were still slightly below the average level for the 1970s (though 20% above the post-1970s nadir of March 1995).

But...

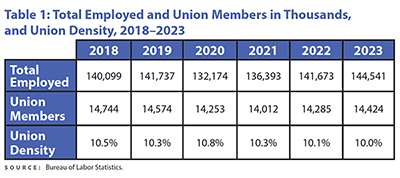

Before anyone starts ballyhooing a new era for labor, however, there is another statistic that needs to be recognized. Union density—people in labor unions as a percentage of total employment—actually declined in 2023, a continuation of the trend for the last several decades. Not only did union density decline, but, even after the increases in union membership in 2022 and 2023, total membership was still below its levels of 2018 and 2019. (See Table 1.)

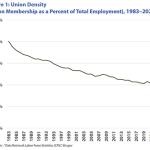

The long trend is shown in Figure 1, with union density in 2023 half of what it was in 1983. Fully comparable data are only available since 1983, but the decline began earlier, with other data showing that union density peaked at 34.8% in 1954. Of course, different segments of the population have fared somewhat differently in this overall trend; people’s experience varies based on gender and race, and on which state and sector of the economy they work in. (See sidebar, “Variations in Union Membership by Various Criteria.”) But the overall experience has been one of major decline in unionization.

Why?

The long and continuing decline in union density is somewhat confounding in light of the clear material benefits that tend to come from unionization. As a 2023 report from the U.S. Treasury Department points out, “One of the most oft-cited benefits of unions is the so-called ‘union wage premium’—the amount that union members make above and beyond non-members... simple comparisons of the wages of union workers and nonunion workers find that union workers typically make about 20 percent more than nonunion workers.” But simple comparisons ignore such factors as union workers producing different products, with different skills, in different places than nonunion workers. When such differences are taken into account, the Treasury report suggests, there is still “a union wage premium of around 10 to 15 percent, with larger effects for longer-tenured workers.” The report further notes: “There is strong evidence that unions improve both fringe benefits and non-wage features of the workplace.”

There are, however, several explanations of the decline in the percentage of workers that are unionized, including seemingly unwarranted inaction by unions themselves. Consider: Structural changes in the U.S. economy have made union organizing more difficult. For example, employment has shifted from large manufacturing plants to large service firms with multiple small sites. In its heyday of the 1930s, Ford’s River Rouge plant in Michigan had 100,000 employees. The U.S. Steel plant in Gary, Ind., had 30,000 employees as recently as 1970. Today, Amazon has 1.5 million employees in the United States spread among some 100 “fulfillment centers” (and administrative offices), while Walmart has about 1.6 million employees and 5,300 stores in the United States. Several fast food chains, though under the aegis of a single firm, have large numbers of separate stores; Starbucks is an example, where unionization efforts, while intense, have had to proceed one small operation at a time. Organizing at large manufacturing plants was never easy, but success meant a huge payoff in terms of new union members.

Also, the particular character of globalization in recent decades has made union organizing more difficult. With the rules of global economic activity structured largely by the U.S. government, firms can readily move abroad, or use the threat—implicit or explicit—of movement to undercut union efforts. Either way, the firms retain access to the U.S. market, yet they pay no cost for the devastation their actions impose on workers and local communities.

The role of political actions, as illustrated by the way globalization has been politically structured, has been a factor undercutting unionization. Especially important, 26 states have “right to work” laws prevent a union and an employer from establishing a contract requiring workers to either join the union and pay dues pay an “agency fee” to the union; nonetheless, workers who choose not to join or pay still have the same benefits as union members. Most of these laws were established in the late 1940s and early 1950s, especially in southern states. Yet, in six states, right-to-work laws were established since 1975, and four of these six in the 21st century. (Michigan established a right-to-work law in 2012, but repealed it in 2023.) In 2018, the Supreme Court, in the Janus v. AFSCME case, ruled that public-sector workers throughout the country were, in effect, covered by the “right to work.”

Since the early 1980s, political actions harming unions have been especially severe, starting with President Ronald Reagan’s firing of air traffic controllers when they went on strike in 1981. During the remainder of the Reagan administration and during both Bush presidencies, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) failed to effectively protect workers from being fired when attempting to form a union. The situation under Democratic administrations has been better, but remedies to employer misconduct can take years and fines for misconduct are small.

Rising aggressiveness of employers and increased sophistication of their efforts to thwart union organizing have been effective. Of course, employers’ opposition to unions is nothing new. From 1950 into the 1970s, however, many large employers did not fight unionization so aggressively. This era of a relative business-labor concord was in part a result of federal legislation—the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, which strengthened labor, and the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which shifted power toward business. Also, important was the compromise agreement between the United Auto Workers auto firms of 1950, often referred to as the “Treaty of Detroit.” The relatively non-aggressive approach by business worked well for employers in an era of fairly strong economic growth and limited international competition.

The widely publicized recent efforts of both Starbucks and Amazon to undermine unionization efforts are examples, however, of the approach that has developed in recent decades. Kate Bronfenbrenner, director of labor education research at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, writing in 2009, stated:

In the last two decades, private-sector employer opposition to workers seeking their legal right to union representation has intensified. Compared to the 1990s, employers are more than twice as likely to use 10 or more tactics in their antiunion campaigns, with a greater focus on more coercive and punitive tactics designed to intensely monitor and punish union activity... Employers have increased their use of more punitive tactics (“sticks”) such as plant closing threats and actual plant closings, discharges, harassment, disciplinary actions, surveillance, and alteration of benefits and conditions. While at the same time, employers are less likely to offer “carrots,” such as granting of unscheduled raises, positive personnel changes, bribes, special favors, social events, promises of improvement, and employee involvement programs.

Employers appear to have increasingly turned to “union busting” law firms and consultants to aid in the implementation of these policies. A 2020 report from the Business & Human Rights Research Centre cites Bronfenbrenner as stating that “companies spend as much as $340 million a year on such services.”

Unions themselves, as a whole, have limited their organizing actions. This limited action by unions is especially important because, first, it is something that unions could directly deal with and, second, it underlies the other constraints on union advances. This limited organizing is sometimes rationalized by the concept of “Fortress Unionism.”

Fortress Unionism

In the short run, there are clear conflicts between efforts by unions to extend their organizing efforts and other union responsibilities—in particular, bargaining and protecting their members from employers’ mistreatment and abuses of union members (i.e., employers’ contract violations). These relatively immediate union responsibilities can include strikes, which, in turn, mean using union resources to maintain a strike fund. There would seem to be, and often are, conflicts between using union resources to support organizing and meeting immediate responsibilities.

Given the difficulties in organizing noted above, it is easy to forego organizing in favor of immediate responsibilities. This approach is “Fortress Unionism,” advocating that unions use their limited resources to protect their existing strengths and forego costly and lengthy organizing drives until the environment (economic structure, political context, employer aggressiveness) changes. But there are two major problems with the “Fortress Unionism” argument: first, the environment is unlikely to change appreciatively without a stronger labor movement—which means a larger labor movement; and, second, it turns out that unions’ resources are not so limited!

On the matter of “limited” resources, while the situation varies among unions, a 2022 study by Chris Bohner of Radish Research demonstrates that U.S. labor unions in the private sector have a very large amount of assets. (Similar data are not available for public-sector unions.) In 2021, a surplus of $2.5 billion of revenue over expenditures by private sector unions contributed to an already large amount of assets. In that year, these unions had liquid assets of $13.4 billion. Of course, some of these liquid assets could be needed for strike funds. Yet, Bohner points out that “financial filings show that organized labor paid out an average of $78 million a year in strike benefits since 2010,” less than 3% of 2021’s surplus income and less than six-tenths of 1% of liquid assets in that year.

Bohner further points out that 20,000 new organizers could be deployed for less than $1.6 billion annually (including salaries, benefits, and administration), a good deal less than the operating surplus of 2021 and a fraction of unions’ liquid assets.

Of course, the financial situation is not the same for all unions, and some unions are giving attention—and resources—to organizing. Yet, Bohner’s research makes it clear that there is not a conflict between using resources for organizing and using resources to maintain existing union strengths.

The Possibility for Organizing

The positive union experiences of 2023 could provide the impetus for a significant increase of union organizing, especially if the strong labor market is maintained. A surge of organizing could in turn weaken some of the forces that have made organizing difficult in recent decades. It could inhibit some of the structural changes, start to alter the political factors, and counter the aggressiveness of employers, all of which have weakened unions and their organizing efforts. It is hard to imagine any of these positive shifts in favor of labor if union density continues to decline as it has over the last several decades.

Furthermore, with a larger share of the labor force unionized, unions could have broad positive impacts on society. There is reliable evidence that unions can raise productivity, resulting from the improvements they bring in workers’ conditions that can create stability, reduce turnover, and generate more effective work in enterprises. Furthermore, strong unions have in the past been associated with greater economic equality, because of both unions’ impact on workers’ wages and their influence on political decisions. The events of 2023 have not yet changed the course of union history, but they still might mark a major shift.

Arthur MacEwan is a professor emeritus of economics at UMass–Boston.

Dollars & Sense is a non-profit, non-hierarchical, collectively-run organization that publishes economic news and analysis, with the mission of explaining essential economic concepts by placing them in their real-world context. We publish a bi-monthly magazine, as well as economics books that are used in college social science courses, study groups and other educational settings. Please consider supporting our work by donating or subscribing.