Presidential Immunity Didn’t Fall out of a Coconut Tree

Today’s excellent New York Times reporting, “How Roberts Shaped Trump’s Supreme Court Winning Streak,” provides blockbuster details on the behind the scenes processes that led to Trump v. Anderson (the Colorado ballot case), Fischer v. United States (the J6 defendants case), and Trump v. United States (the immunity case). Today’s Weekend Reading hopes to be a useful companion piece to put the new reporting in context.

The article begins the story in February 2024, and necessarily reports on what happened after Roberts’ February 22nd memo. However, this leaves the impression that addressing the question of presidential immunity sprung itself on the Court. Indeed, it’s impossible to imagine that none of the justices formed opinions about the legality of Trump’s post-election activities until a case came to them three years later. And, although we didn’t know it at the time, Roberts and the other justices were fully aware of Ginni Thomas’ encouragement of the insurrection, as well as insurrectionist flags flying at the Alito residence.

Yet Roberts made no effort (and seemingly had no interest in) fashioning an opinion that might have garnered wider acceptance. Indeed, the February 22nd memo makes clear that Chief Umpire Roberts had decided the final score long before the players took the field.

In a way that is typical of even negative reporting about Roberts, the Times piece’s key paragraph holds back from the full force of the wholly justifiable conclusion that the final decisions reflect Roberts’ proactive intentions rather than reactive problem solving:

In a momentous trio of Jan. 6-related cases last term, the court found itself more entangled in presidential politics than at any time since the 2000 election, even as it was contending with its own controversies related to that day. The chief justice responded by deploying his authority to steer rulings that benefited Mr. Trump, according to a New York Times examination that uncovered extensive new information about the court’s decision making (emphasis added).

The passive tense “found itself entangled” and “the chief justice responded” inverts reality, as Roberts was responding almost entirely to entanglements of his own making. But for his uncompromising approach, Trump v. Anderson could have been quickly and uncontroversially decided unanimously, Trump v. United States might have been decided with at least one “liberal” justice, and Fischer did not have to be decided at all.

Fischer v. U.S.

Let’s begin with the easiest of the three cases mentioned in the Times piece. The article provides no background on who decided to entangle the Court in this case by voting to grant cert.

SCOTUS routinely rejects appeals with far graver implications than Fischer in terms of chilling dissent, which was the concern raised in oral arguments and in the final opinion. A notable example they didn't take up, despite its having far more egregious and broader implications for chilling speech, was a case involving a Black Lives Matter protest. The Court allowed the organizer of that protest, which was non-violent save for a single protester throwing a rock at a police officer, to be sued for that one protester’s actions.

Moreover, the Alito switch on Fischer occurred shortly after the New York Times reporting about the insurrectionist flags flying at his homes. Today’s Times report caveats: “While that timing is suggestive, it is unclear whether the two are linked.” Remember, if you believe, as basically everyone who wasn’t born yesterday does, that they are linked, this is an indication that Roberts saw Alito getting caught flying the flag as the problem – not flying the flag in the first place, which we know he knew about three years ago.

Trump v. Anderson

Unlike Fischer, the Court clearly had to take this case. Today’s reporting confirms what was obvious by the end of oral arguments – that there was broad agreement among the justices that Colorado had exceeded its authority in removing Trump from its primary ballot. Thus, the principles enunciated in the per curiam began with unanimous agreement and could have been delivered with alacrity.

But Roberts didn’t do that. Instead, he went further than necessary to settle the case – effectively disabling section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which prohibits those who “shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof” from holding office. Indeed conservative legal scholars including William Buade and Michael Stokes Paulson, as well as retired judge Michael Luttig, wrote convincingly that disqualification was in order.

For the first time since it was drafted, according to the majority, the insurrection clause of the 14th Amendment cannot be enforced unless Congress enacts legislation first. Now, the Amendment has no power unless Congress enacts legislation first. And the Roberts majority decreed this while sidestepping the question of whether Trump had engaged in an insurrection.

Trump v. United States

Let’s begin by taking a longer view of the relationship between the Republican appointees and Trump’s efforts to overturn the election results. Again, it’s not as if the “need” to address the question of presidential immunity fell out of a coconut tree in February 2024. Consider:

-

In February 2021, Mitch McConnell and other Republican senators who voted to acquit Trump publicly stated that they believed he could be criminally prosecuted.

-

In February 2021, Roberts, and likely most or all of the others were aware of Ginni Thomas’ encouragement of the insurrection, and possibly Alito’s wife’s as well. .

-

In August 2023 they were aware of the charges for which Trump was indicted.

-

In December 2023, they were aware of Judge Chutkan’s rejection of Trump’s immunity claims.

-

In December 2023, although they clearly thought the broader questions needed to be decided by them for the ages, they went along with Trump in rejecting Jack Smith’s request to expedite consideration of presidential immunity.

-

In January 2024, they heard the oral arguments of Trump’s appeal in which even his lawyers conceded there were aspects of the indictments that were not covered by presidential immunity.

-

In early February 2024, they were aware of the DC Circuit Court of Appeals decision.

The reporting makes clear that most, if not all, of the Republican appointees had already formed their judgments well before Trump’s appeal of his unanimous and emphatic loss at the DC Circuit Appeals Court. But Roberts made no effort (and seemingly showed no interest) in fashioning an opinion that might have garnered wider acceptance, if doing so came at the expense of trimming any of the maximalist aims of the most political justices on the Court. (The article indicates that in June, Justice Sotomayer “signaled a willingness to agree on some points in hopes of moderating the opinion.”)

That indifference to compromise is literally unprecedented in any Supreme Court case of similar magnitude other than Bush v. Gore during the Vinson, Warren, Burger or Rehnquist eras. What insider reporting there is of the most important decisions before that, whether it’s Brown or Roe, reveal strenuous efforts to fashion decisions that could bring along as large a majority as possible.

As I explained in “Tipping the Scales: The MAGA Justices Have Already Interfered with the 2024 Elections” and “Breaking the Law: Trump Is the Means, Not the End,” Roberts stands alone in bringing no one outside of his ipse dixit majority along for any of his most significant rulings.

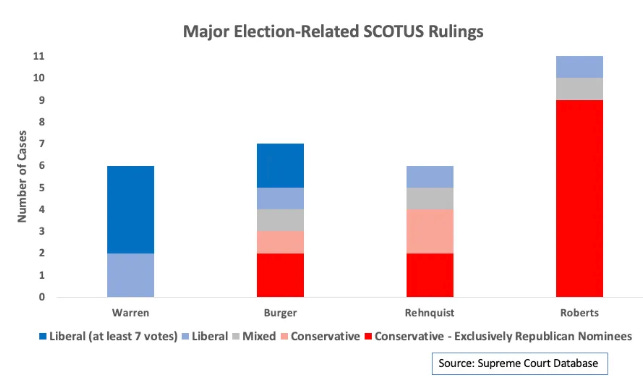

First, with respect to election related cases, the following graph shows the number of important election-related rulings each Court made since the 1950s, broken down by ideology. The dark blue represents liberal consensus rulings with 7 or more votes; the dark red represents conservative rulings where the majority consisted only of Republican nominees.

Moreover, the overwhelming majority of civil rights related precedents overturned by the Warren and Burger courts were decided with at least 7 votes. As well described in various accounts, Chief Justice Earl Warren worked strenuously to fashion a unanimous opinion in Brown, which included the assent of Justices Hugo Black (formerly a senator from Alabama) and Stanley Reed, who initially said he “opposed abolishing segregation.” By contrast, none of the civil rights precedents overturned by the Rehnquist Court, and fewer than 1 in 5 of those overturned by the Roberts Court, had as many as 7 votes.

The Roberts Majority Is Not “Conservative”

In almost all Supreme Court coverage, the six Republicans are labeled “conservative” – suggesting that in the context of these cases, their judgment should be thought of in terms of adhering to eternal conservative principles. In fact, as I detailed in “To the Supreme Court, the 20th Century Was Wrongly Decided,” Federalist Society-approved jurists are allowed to call themselves “conservative” even though they readily ignore conservative principles whenever it’s necessary to do so to realize their substantive aims. Similarly, their commitment to “originalism” has never been anything more than a post-hoc rationalization for rulings that have no other plausible explanation than advancing the interests of the FedSoc coalition.

Just look at this list of major interventions by FedSoc judges that have had serious consequences for our elections. For more detail on each intervention, see Tipping the Scales: The MAGA Justices Have Already Interfered with the 2024 Elections. Taken together, these interventions have not only literally decided who would be president (Bush v. Gore) but have rewritten what had been the settled rules of democratic elections in favor of those plutotheocratic interests.

Thanks for reading Weekend Reading ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribed

For more Weekend Reading on SCOTUS:

For more Weekend Reading on Trump Accountability:

Weekend Reading is edited by Emily Crockett, with research assistance by Andrea Evans and Thomas Mande.

Michael Podhorzer @michaelpodhorzer is former political director of the AFL-CIO. Senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. Founder: Analyst Institute, Research Collaborative (RC), Co-founder: Working America, Catalist. He publishes Weekend Reading. (weekendreading.net)