CAIMAW’s 60th Anniversary

On September 21st, 124 retired trade unionists, activists, and various friends, allies, and families of the labour movement congregated inside the Unifor union hall on 12th Street in New Westminster, British Columbia. The occasion was the 60th anniversary of the Canadian Association of Industrial, Mechanical, and Allied Workers (CAIMAW).

If the name CAIMAW is unfamiliar, it’s because the union technically no longer exists. After a storied and inspiring (yet criminally underwritten) history beginning on June 14th, 1964, when 560 dissident workers in Manitoba broke away from the International Molders Union and formed their own union. CAIMAW’s 6,500 members across British Columbia, Alberta, and Manitoba merged with the Canadian Autoworkers (CAW) on January 1, 1992.

Select former CAIMAW locals live on today under the Unifor banner, formed in 2013 after a merger between the CAW and the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada (CEP). The union hall in New Westminster made an appropriate venue for the anniversary, which celebrated CAIMAW’s past while reminding attendees just how different the Canadian labour movement was sixty years ago.

A time of rebellion

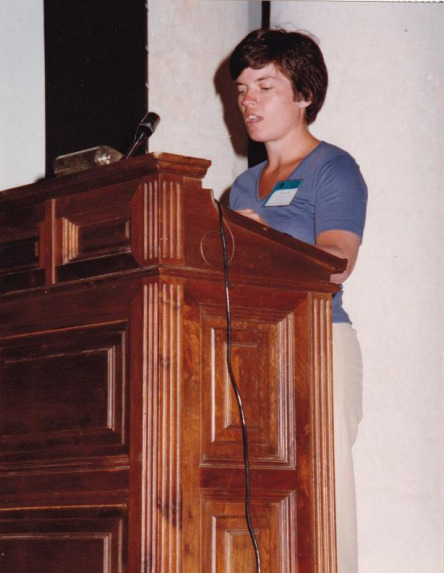

The historical circumstances in which CAIMAW was formed were expertly laid out by Cathy Walker, who kicked off the event’s formal speeches. Much like the name CAIMAW, the name Cathy Walker is not known well enough in Canadian labour. Active in the British Columbia-based Canadian Electrical Workers (CEW) local that merged with CAIMAW in 1969, Walker helped to organize workers into the union and eventually became the union’s National Vice-President of Health, Safety, and the Environment. Walker became the director of the same department in the CAW after the merger with CAIMAW, making her one of the few female directors in the union at a time when its leadership was dominated by men.

Photos above: Cathy Walker became well respected by Canadian and American unions alike for her commitment to health and safety. Photos courtesy of the 60th Anniversary Organizing Committee and Garry Worth respectively.

As Walker recalled in her speech, “the 1960s was a time of rebellion.” The peace movement railed against the threat of nuclear war and protested the American invasion of Vietnam, while feminists, civil rights activists, and militant young leftists agitated for women’s rights, racial equality, and a socialist response to the global capitalist order. Such rebellion was met with “virulent anti-communism,” Walker reminded attendees, which in the American and Canadian labour movement meant the expulsion of left-wing trade unionists by the labour movement’s upper brass, regardless of the veracity of their ties to communism.

Rather than suppress the radical potential of the labour movement, the counterrevolutionary fervour of the Cold War engendered further worker militancy. In 1966, workers at the Lenkurt Electric plant in Burnaby, a suburb of Vancouver, a majority of them women, staged a walkout in protest of forced overtime. The leaders of the strike, among them George Brown and Frederick Haydyn “Jess” Succamore, were expelled from their union, Local 213 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, for their part in the strike. Local 213’s leadership later signed a contract with Lenkurt management behind closed doors, forcing the strikers back to work.

In response to the unacceptable outcome of the Lenkurt strike, Brown, Succamore, and others founded the Canadian Electrical Workers (CEW) union on November 6th, 1966. With the aid of Jack Scott’s Progressive Workers Movement, the CEW organized several electronics plants in British Columbia. It was this organizing drive that brought Walker and other stalwarts like Peter Cameron into the CEW’s fold. After the formation of the Confederation of Canadian Unions (CCU) in 1969, the CEW merged with CAIMAW, further democratizing the latter and elevating Brown, Succamore, Cameron, and Walker into key positions in the union and, eventually, the B.C. labour movement.

In attendance at the celebration were Brown and Succamore’s surviving family. Ione Brown, George Brown’s daughter, delivered a stirring and empowering tribute to her father, who passed away in 1974. Though only 46 years old, Brown had built a union of militant trade unionists that pushed the Canadian labour movement into progressive places …. even if that progress came at the cost of significant animosity.

Those outside of CAIMAW and the CCU remember the ensuing acrimony well. “I’m so old, I used to be a labour reporter,” Rod Mickleburgh jested at the start of his brief speech. A labour reporter on the “night beat” for the Vancouver Sun,and later a journalist for The Globe and Mail, Mickleburgh covered a number of dramatic showdowns in CAIMAW’s history during his career. One such episode was CAIMAW’s campaign to instigate a breakaway from the United Steelworkers of America at the Cominco Smelter in Trail, B.C. in the early 1980s. Though ultimately unsuccessful, CAIMAW rallied a significant number of dissident Steelworkers and signaled to the American union that an independent alternative was not only available to workers, but a viable means of changing their working lives.

The Cominco smelter in Trail, B.C. c. 1970s, where CAIMAW very nearly displaced the United Steelworkers as the bargaining agent in the early 1980s. Photo courtesy of the 60th Anniversary Organizing Committee.

CAIMAW’s relations with Canadian unions were far more amicable. Former NDP Provincial MLA for New Westminster and Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Judy Darcy recalled how her trade union activism and leadership, first with the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) and later in the Vancouver-based Hospital Employees’ Union, was informed by her coalition work with CAIMAW, the CCU, and other CCU affiliates such as the Canadian Textile and Chemical Union.

International solidarity

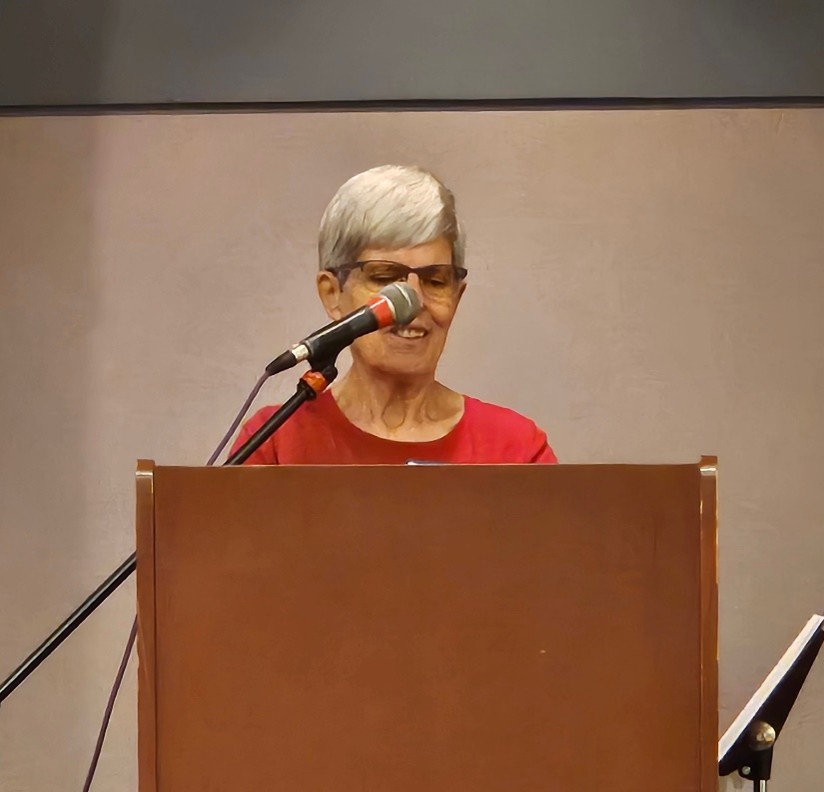

Attendees were also reminded that CAIMAW’s nationalism was built on a strong foundation of international solidarity. Ken Luckhardt, who along with fellow lifelong anti-apartheid activist Brenda Wall was recently awarded the Order of the Companions of O.R. Tambo award by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, spoke about CAIMAW’s decisive involvement in the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) Solidarity Committee in the 1980s and 1990s, a broad coalition of Canadian trade unions committed to supporting SACTU and its membership in its struggle against the South African apartheid regime. The SACTU Solidarity Committee relied on fundraising efforts and donations from Canadian unions, as well as educational sessions that informed Canadian workers how they could stand in solidarity with South African workers.

Ken Luckhardt (right) and Jef Keighley (left). Luckhardt chaired the SACTU Solidarity Committee while Keighley’s activism against apartheid within CAIMAW was recognized by the CAW. He led the Canadian trade union delegation to South Africa upon the election of Nelson Mandela.

Luckhardt did not mince words when comparing CAIMAW’s support for SACTU to that of the wider labour movement, particularly the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC). In keeping with its long-held anti-communist philosophy throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, the CLC dismissed SACTU as a communist-run organization. It was not until CAIMAW’s various campaigns, ranging from collective bargaining strategies to outright work stoppages, that the CLC started to reassess its treatment of SACTU and its approach to the apartheid regime writ large. To be sure, the CAW and CUPE’s support for the SACTU Solidarity Committee were also significant in shifting the CLC’s attitudes.

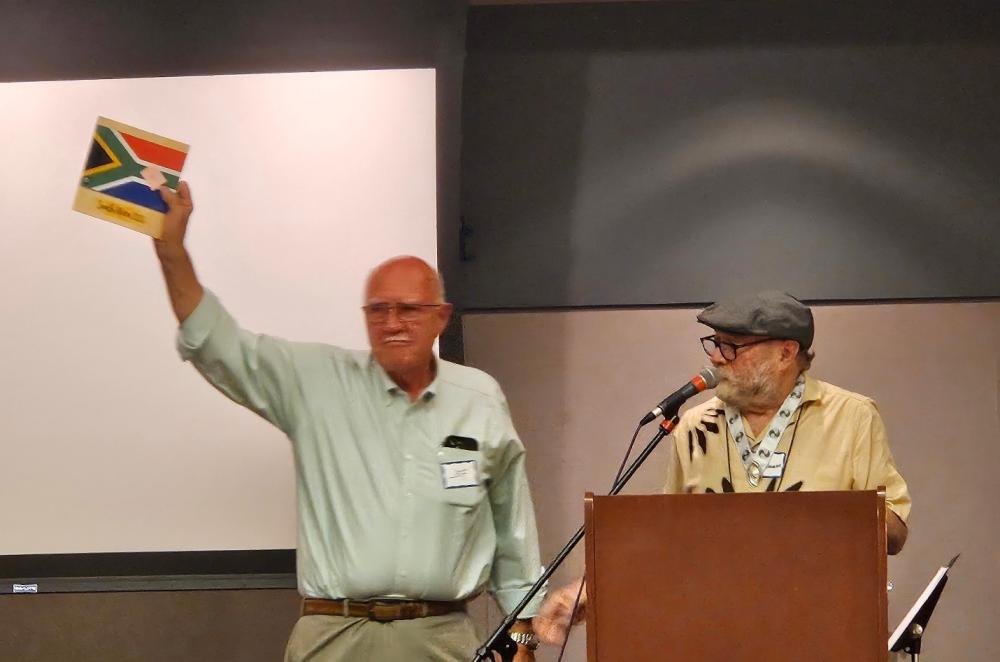

Many other CAIMAW members, leaders, activists, and allies spoke. Life-long brothers and sisters in struggle reconnected and reminisced over drinks and hors d’oeuvres. The event ended on a high note, with Jef Keighley, originally from CAIMAW Local 14, leading attendees in the singing of classic labour anthems such as “Union Maid” and “Solidarity Forever.” “The thing about labour songs,” Keighley told the crowd, “is that they’re meant to be sung.”

Jef Keighley (right), Art Farquharson (middle), and Janet Hall (left) rounded out the celebration with a performance of classic labour songs. Photo courtesy of Garry Worth.

For a few hours that Saturday afternoon, CAIMAW was alive and well, and the radical spirit of trade union militancy with it.

The author wishes to thank the members of the 60th Anniversary Organizing Committee – Cathy Walker, Janet Hall, Roger Crowther, Lamber Sidhu, Pete Smith, John Bowman, Jef Keighley, Silvia Simpson, and Denise Kellahan – for their invitation to the event and their permission to publish this account. Thanks are also due to Garry Worth for his permission to reproduce his photos of the event.

RankandFile.ca was established in 2012 as a Canadian labour news website which seeks to:

- provide readers with factual and informative labour news

- help build solidarity for workers in struggle

- develop a coherent analysis of the labour movement

- contribute to the building of rank-and-file labour networks