Viet Thanh Nguyen Broke a BDS Rule. Now He Is Its Vocal Advocate.

Viet Thanh Nguyen feels the need to clarify a thing or two. In November, a Hebrew translation of the Vietnamese-American writer’s 2017 short story collection “The Refugees” was released by the Israeli publishing house Babel Publishers. But this came just weeks after he had joined over 1,000 prominent authors — including Arundhati Roy, Sally Rooney, and Ocean Vuong — in signing a call to boycott Israeli cultural institutions, including publishers.

The signatories vowed to refuse collaboration with institutions that are “complicit in violating Palestinian rights, including through discriminatory policies and practices or by whitewashing and justifying Israel’s occupation, apartheid, or genocide,” or that have “never publicly recognized the inalienable rights of the Palestinian people as enshrined in international law.” Suddenly, Nguyen found himself violating his own pledge when it mattered most, as Israel’s onslaught on Gaza continued to devastate the strip, killing over 45,000 Palestinians and wounding more than 106,000 others.

Nguyen had, in fact, already expressed support for the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement back in June 2016, calling the occupation one of the “contemporary injustices that we struggle to remember.” Then, too, his remarks preceded the publication by Babel of a Hebrew translation of his Pulitzer Prize-winning debut novel, “The Sympathizer,” the following year.

Nguyen made headlines last October, as Israel launched its assault on Gaza following the Hamas attack on southern Israel, when he signed an open letter calling for an immediate ceasefire. Just days later, the renowned New York Jewish cultural center, 92nd Street Y, canceled a scheduled event with him, prompting a number of authors to withdraw from planned appearances and staff to resign in protest. For Nguyen, this also marked the beginning of what he describes as a period of profound “introspection” that forced him to interrogate his relationship to BDS.

Refusing interviews with what he calls the “mainstream Israeli media,” Nguyen knows his decision to support the boycott, juxtaposed with the publication of his work in Israel, not only carries immediate repercussions — it demands grappling with questions of accountability, complicity, and the role of writers and cultural movements in political movements, especially during times of mass violence. His position on Israel today, as he put it in an interview with +972 Magazine, is unequivocal: no collaboration without a clear renunciation of colonization and apartheid.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you decide to sign the pledge to boycott complicit Israeli institutions?

I signed the BDS resolution in 2016. At that time, many of my friends and colleagues in different fields had already signed on, so it had been in my consciousness for a long time. [And I had long been aware of] the question of Palestine, ever since I used Edward Said’s “Orientalism” to write my senior thesis on Graham Greene.

I think the current war really focused my attention on Israel and Palestine, as well as the role of the United States and my own position in this situation — as an American citizen, a refugee from the Vietnam War, and someone who came into political consciousness as an Asian American.

My immediate reaction to [the October 7 attack] was very visceral because I had a very good sense of what was going to happen immediately as a consequence. So I signed a ceasefire letter a few days later, along with 700 or so other writers and intellectuals from around the world. That was really the predecessor to signing this last statement that calls for boycotting literary institutions and publishers.

You signed a contract to translate and publish “The Sympathizer” in Hebrew with Babel Publishers in 2016, the same year you declared your support for BDS. How did you see your role speaking to Israelis back then, and how do you see it today?

I don’t remember the sequence of events when I signed the BDS statement and when I signed my contract with Babel Publishers. I do remember that after “The Sympathizer” was about to come out in Hebrew, the fact that I had signed the BDS statement came up with my publisher. At that point, I just assumed there would be no more books of mine published in Israel, so I didn’t think twice about it after that.

Then, around the same time that I signed the recent pledge, I was notified by my publisher that there was going to be a Hebrew translation of “The Refugees” — and I had no idea [that this was in the works]. I knew I had signed a contract in 2016 or 2017, but I heard nothing from my publisher after that. So I just assumed, given the consequences of me signing the 2016 BDS resolution, that there was not going to be a second book. It was a complete surprise that the book was already in print and on its way to publishers.

Honestly, the real explanation is that I was not particularly focused on BDS even after signing the resolution back in 2016. I think that I was on the same side politically, but my energies and my focus were not there. That’s my mea culpa on that.

Since then, and especially after October 7, I really did focus my attention [on Palestine]. I’m grateful that after signing the ceasefire letter, one of my events was canceled at the 92nd Street Y in New York City, which began a sequence of events that required me to become much more introspective and serious about the nature of BDS and how [it connects to] all these issues in my life.

The history of American colonialism — which both led the United States into Vietnam and turned me into a refugee — is a history I understand very well. But I hadn’t made that connection to American involvement in and narrative around Israel — which has actually shaped my own life in ways that I was not cognizant of — because, like many other Americans, I had been subjected to decades of propaganda.

My sudden understanding that “The Refugees” was going to be published by an Israeli publisher happened within a week of signing the pledge. I have been in touch with Babel declining interviews with the mainstream Israeli media, and [I’ve also been in touch] with activists involved in BDS and the Palestinian literature scene to try to take various public stances and clarify my own position. Any prize money, for example, that is associated with Israeli investments — including the Baillie Gifford prize — I have tried to use for the benefit of Palestinian causes.

What is the value of taking a public stance as opposed to silent refusal, which I’m sure many in the cultural field are practicing right now?

Signing letters and petitions is important, but for me, there is a distinction between signing something and articulating a public stance. As I mentioned, I signed one in 2016 or 2017 but didn’t take a very public position. It wasn’t a willful silence in the sense that I was trying to dodge anything; it was simply that my attention was not focused on these issues that we’re discussing today.

Articulation is crucial for a number of reasons. First, it helps me to think through political, historical, and aesthetic issues. That was why immediately upon signing the ceasefire letter back in October, I also articulated on Instagram why I signed the letter, which elaborated in ways that were a little bit different than what the letter itself actually said. I quoted the letter but also affirmed my support for BDS and said something to the effect of “count me among the human animals.” Apparently, that was more incendiary than simply signing the letter itself.

My inspirations have always been committed writers, going back to W.E.B. Du Bois, Franz Fanon, Jean Paul Sartre, Edward Said, and others. They have always made an imprint on me not only because of their intellectual and artistic work, but also because they were doing political work in a very public way.

Babel is considered a left-wing Israeli publishing house. It has published books by Naomi Klein, Howard Zinn, even Mahmoud Darwish in Hebrew. I’m curious how you see your relationship to an Israeli audience today in this moment of genocide. How do you envision actually talking to them, if at all? How do you reconcile the need for a boycott with the importance of maintaining a dialogue with Israeli authors, publishers, or intellectuals who support Palestinian rights but who might not answer the demands of this particular pledge because of its potential financial repercussions or because of all the other pressures that the Israeli left faces?

I have a lot of sympathy for the Israeli left. I think about this issue analogically: I would be totally in support of a movement to boycott the United States. We deserve to be boycotted. I think that everything that the BDS movement accuses Israel of doing, the United States has done and still does in many circumstances. It has become normalized in the United States to support genocidal regimes; Israel is not the first in this regard. We are still a settler-colonial society, in which the history of genocide is embedded into our everyday structures and policies.

In this hypothetical scenario, what would my reaction be if the United States were boycotted? And what would I want from people who were critical of the United States? If the stance was that there are conditions that Americans must meet in order to engage with the rest of the world, I would want to know what those conditions are. And if those conditions were, “You have to recognize that settler colonialism exists, you have to recognize that genocide is a practice of your society, you have to support decolonization, you have to support indigenous rights, you have to support the Land Back movement,” I would say, “Yes, absolutely.”

These are things we need to do. And if we don’t, then perhaps we should be persona non grata in various circumstances. That is the penalty that we should pay as Americans. Would I feel bad? Yes, of course, if [it meant] opportunities were foreclosed for conversation and dialogue and trips.

This is my approach to the Israeli situation, and I’ve constructed this analogy out of a structural connection. Of course, the Israeli left is still embedded in the structural oppression of Palestinians and of the occupation of Palestine. So even with all of the genuine sympathies I assume that many in the Israeli left feel for Palestinians, [there is a need] to recognize the complicity of every part of Israeli society with what is taking place, and to make a statement in that regard.

So a publishing house that wants to continue working with you would have to make some kind of public statement that recognizes their own complicity, and distance itself from genocide, war crimes, or crimes against humanity in order to continue working with you?

Yes.

Do you find that your personal history has been a defining factor in your decision to be vocal about the Palestinian cause? And do you think that perhaps people with a different background or life story would be less inclined to take such positions?

I think our personal history is always going to be intertwined with the kinds of judgments and decisions that we make. But if we simply talk about people who occupy a similar situation as me, whether those be Vietnamese refugees or Asian Americans, a lot of them are like every other American: they are invested in settler colonialism, American global hegemony, and American mythologies. I don’t think a good number of them are necessarily sympathetic to Palestinians or the Palestinian cause, so I think there has to be more than simply a question of identity.

At the very least, there has to be some type of political consciousness that recognizes both the history of the United States and how that has brought it into the role of supporting Israel, and the current narrative that Israel projects and that the mainstream in the United States amplifies. I think that this type of political consciousness merges with a moral awareness that there are, at the very least, war crimes being committed [in the form of] mass murder, structural starvation, and a siege.

I think there are a good number of Americans, including Vietnamese or Asian Americans, who are not eager to see the images or hear the sounds that are coming out of Gaza. [This is related] not simply to the issue of Gaza, but everything that it represents in terms of American foreign and domestic policy. So if you’re an American who doesn’t want to see how the United States operates in the rest of the world, you’re definitely not going to want to see how it’s operating in Israel as well.

You have been re-thrust into the limelight over the last year for your support for the Palestinians. How do you gauge the change that is happening around you in the literary world? Do you think there are gains being made for the movement?

I think that there obviously have been gains at the level of consciousness for Palestinian liberation. It has been pretty astonishing how rapidly the dominance of Israeli and U.S. propaganda has diminished over the last year. It hasn’t been defeated, but the erosion has been incredibly fast, and I say this as someone who himself was subjected to this kind of propaganda.

The struggle on the part of Palestinians to contest this narrative dominance has been going on since at least 1948. My most vivid [introduction to] Palestine came from the movie “Exodus,” which I watched when I was 11 or 12. That and my exposure to Jewish-American literature and culture was it, until I read Edward Said. But I think October 7 and everything that happened subsequently seems to have accelerated the critique of that propaganda at a pace that I haven’t seen before.

On the other hand — and Palestinians have noted the terrible irony of this — these narrative gains contrast with the utter destruction of Gaza. How will this resolve itself? I’m not certain. But the positive sign, for me, is that the narrative struggle has transformed support for Palestinians and [has ignited] an increased awareness of how Western global hegemony works to suppress populations.

Watching the horrifying spectacle in Gaza allows people to connect it to the other horrifying spectacles that have been a part of the Western domination of the Global South for decades. And it has allowed critics of Israel and the United States to make an important argument: that the very notion of international law is based on power and violence.

How has life changed for you on a more personal level since October 7?

[The past year] has been transformative — it has brought me back to [a similar transformative period during my time as a university student] at UC Berkeley, where I was immediately radicalized. At Berkeley, I was engaged in both intellectual and political transformation as a student activist and an aspiring writer. I came out of this morass of adolescence and a great confusion about who I was as an individual, as an American and a Vietnamese, and my place within those histories; suddenly, the veil dropped from my eyes.

October 7 and everything that happened in its wake — including domestically, within the United States — was an equivalent transformation, encouraging me to clarify what I already understood: that American domestic inequality and racism have never been separate from the operations of American foreign policy and military power.

+972 Magazine)

You mentioned the responsibility of writers to also be political agents. What do you believe is the responsibility of writers and artists when it comes to addressing injustices like those in Palestine through their art, and how can they use it effectively to challenge dominant narratives?

I think a writer’s first responsibility is to the art: to make sure that your sentences are beautiful and clear. There is power in language in the political sense, but also at an emotional level, an intellectual level, and an artistic level. Our commitment is to being as honest and as truthful to the language, but then to our emotions, and to the stories that we want to tell. From that comes great art, great beauty, and great insight into who we are as individuals, as writers, and as members of our society.

I emphasize this because I think that is how, as a writer, one has not just an aesthetic consciousness but a moral consciousness. When one encounters the corruption of language and narrative, that is the thing that writers are prepared to see. There is no conduct of war, there is no abuse of power, without the abuse of language. And that is why the question of physical and symbolic violence cannot be separated: physical violence has to be justified by symbolic violence and vice versa.

When I say that writers have responsibilities and obligations, it is not an imposition of politics into the realm of writing. Rather, it is what we do and who we are that should prepare us to be sensitive to the abuse of power through language, ideas, and symbols — and ready to speak out about them, by signing letters, protesting at marches, and writing statements or essays. Not enough writers do that, but that’s the bare minimum.

The other challenge is that a lot of writers are introverts, and are not necessarily braver than anybody else when it comes to signing a letter or putting themselves on some kind of front line. I don’t expect a higher degree of courage from writers — I just expect a higher degree of insight.

I think it’s also equally challenging to think through how to translate this political consciousness and sensitivity to language into the art itself. I believe that all art is political, either because it affirms the status quo in some ways or because it engages in friction against it, and against dominant and normative modes of however the culture operates. But I’m very reluctant to have any prescriptions about what that means and how that looks.

We all have to internalize and determine in our own private confessional to what degree our writing is political and whether it affirms a status quo or challenges it. And the beauty of that is that there’s so many ways to undermine the status quo through a political idea of literature. Unlike political parties and governments, writers shouldn’t be obligated to come up with certain platforms, but rather to heed our own inner authentic voice about how to be truthful to ourselves.

You mentioned “Exodus” earlier and how your experience with the film — which had enormous influence — reflects that of many Americans. Such a direct piece of propaganda, packaged as art, also raises a question: what is the value of creating art — and, especially in times of genocide, art that doesn’t directly confront the horror? Can art help to undermine or expose propaganda, and how do we come to terms with not necessarily seeing the immediate impact of our work?

Absolutely. I’ve been thinking about this since I was 19. A movie like “Exodus” is absolutely propaganda. In Israel there seems to be a concerted state-level effort at propaganda; in the United States it’s different. Hollywood is America’s unofficial Ministry of Propaganda. There certainly are state-level operations, but the power of American ideology is such that you don’t actually need an official ministry because it circulates everywhere, including among liberals.

[In this context,] all of these images coming out of Gaza — people just filming their own lives with their phones — is a form of resistance that we shouldn’t overlook. It’s not to romanticize the fact that Palestinians only have phones and the United States and Israel have F-35s and aircraft carriers and missiles. But it’s to say the same technology that produces all these gigantic things also produces these phones that allows these stories to emerge. I don’t know what the long-term effect of those stories will be, but they are transforming the dominant narrative in crucial ways.

Just as I take hope in what it is that the writer or the artist can or should do, I resist this idea that even in moments of urgent crisis, we all have to do the same thing. There are some people who are really good at certain roles — staffing the political organizations, leading marches in the streets — and some people who are not.

The introvert working in isolation on whatever it is that they find to be beautiful, whether it’s a poem or whether it’s a pair of shoes — they’re both necessary. I don’t elevate the poem over the pair of shoes. There’s something beautiful in making shoes for people to wear, just as there is something beautiful about writing a poem for people who need it at a particular moment, just as there is something beautiful about the organizer who gets us involved in a march or in a sit-in.

We are all capable of contributing to the movement in the world that we want to see, and none of these things should be denigrated because we don’t know what’s going to survive. That pair of shoes is going to carry somebody from one place to another — it can help them live. And who knows what that person can become. That poem can survive: it’s an expression of someone’s humanity and beauty. And even after they’re dead, that poem can be found by somebody else. It’s not that all poems will be found or that all shoes will deliver us to someplace beautiful, but you need to have a thousand shoes and a thousand poems for a few to survive.

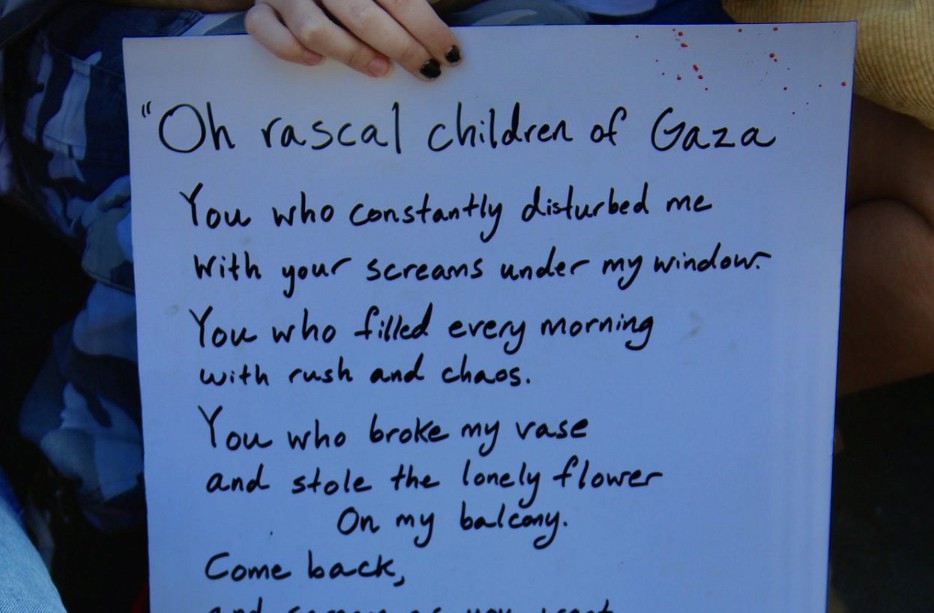

I don’t want to over-romanticize. There are at least 44,000 dead Palestinians, but there are also still hundreds of thousands left who are writing their poems, speaking their stories, recording their videos. Some of those will survive, and that is what we will be left with 50 years from now, however the political situation turns out. We will still need an archive of what people went through, and in some museum or some archive there will be those poems, those videos, those stories. There will be some place with those shoes, too.

I take hope in that, despite all of the violence and terror that we’re seeing now. I can look back on previous moments in history and see that there have been equally outrageous and horrific times in which many people died, and yet we still have a record of some of those stories. That’s not enough, but it is something powerful that remains.

We’re living through an onslaught of horrors. The election of Donald Trump, his appointees, the ongoing genocide in Gaza, climate catastrophe, this boomerang effect of American imperialism coming back to haunt the United States. How, as a writer, do you stay focused and keep some kind of flicker of hope alive in this moment?

I think there are people who feel completely overwhelmed or utterly shocked by the current circumstances. But my parents were born in the 1930s in rural Vietnam under French colonialism. When they were children, they survived a famine in the north that killed at least 1 million people. When I was a kid, my mother would tell me a story about seeing a dead child on a doorstep in her village. They became refugees twice, in 1954 and 1975. We left behind my sister.

Three million people died in the Vietnam War. I grew up saturated with these kinds of stories with a sense of tremendous loss and bitterness in the Vietnamese refugee community; this was a people who felt that they had lost everything and been betrayed. Their whole world had been shattered.

I grew up in a Catholic refugee Vietnamese community where every week, we would go through the rituals of thinking about sacrifice and martyrdom. People had given their lives for their beliefs in the religious sense, but also in the political sense, considering the history of Vietnam in the 20th century. I learned from all of this, especially from my parents, the necessity of endurance and sacrifice and struggle. They were not political people in the sense we have been discussing. But to me, that gave hope. So many people had been lost, but so many other people had survived. And how did they survive? They just endured. They did everything they had to do to live through this awful history through the 1930s to the 1970s in Vietnam, and then as refugees in the United States.

So in our present moment we have Donald Trump and everything that he represents, and all the global crises, from Israel to Ukraine to Russia to Sudan. It is not to trivialize anything to say that these things have happened before, or the fact that millions of people have died as a result of similar things happening before. It is to say that people have endured through their art, through their politics, and through the struggles of simply trying to ensure that their families and communities survive in every way that they can. I find hope in that.

Obviously, we do wonder if this is the final cataclysm with climate change and nuclear war. Again, not to trivialize that, but as human beings, we’ve always lived with a sense of apocalypse in every era. And so, we have to find ways to endure. For each of us, that will be different. But we endure because we find things in people that we love. My parents sacrificed because they love Jesus Christ, because they love their family, they love their children. They were willing to undertake any risk to ensure their family would survive. And so we begin with the small.

And likewise with our art or our shoes or whatever our passion is — that keeps us alive too. We have to make money. We have to take care of our families. We have to get through the next tragedy and horror, but then we have to do something that we believe in as well.

Whatever it is, the endurance of doing that thing reminds us that we are human, that we can hopefully survive, and that we can pass something on to our children, our families, and our communities. This is not a guarantee of anybody’s survival. It’s simply finding meaning in the practice of endurance, focusing on the small with the hope that if we can save the ones we love, we can save all of us as well.

[Edo Konrad is the former editor-in-chief of +972 Magazine.

Alaa Salama is the Audience Engagement Manager at +972 Magazine.]

Our team has been devastated by the horrific events of this latest war. The world is reeling from Israel’s unprecedented onslaught on Gaza, inflicting mass devastation and death upon besieged Palestinians, as well as the atrocious attack and kidnappings by Hamas in Israel on October 7. Our hearts are with all the people and communities facing this violence.

We are in an extraordinarily dangerous era in Israel-Palestine. The bloodshed has reached extreme levels of brutality and threatens to engulf the entire region. Emboldened settlers in the West Bank, backed by the army, are seizing the opportunity to intensify their attacks on Palestinians. The most far-right government in Israel’s history is ramping up its policing of dissent, using the cover of war to silence Palestinian citizens and left-wing Jews who object to its policies.

This escalation has a very clear context, one that +972 has spent the past 14 years covering: Israeli society’s growing racism and militarism, entrenched occupation and apartheid, and a normalized siege on Gaza.

We are well positioned to cover this perilous moment – but we need your help to do it. This terrible period will challenge the humanity of all of those working for a better future in this land. Palestinians and Israelis are already organizing and strategizing to put up the fight of their lives.