José ‘Cha Cha’ Jiménez, Human Rights Activist and Former Chair of Young Lords, Dead at 76

José “Cha Cha” Jiménez, a human rights activist who co-founded the Rainbow Coalition and served as chairperson of the Young Lords organization, died Friday. He was 76.

Mr. Jiménez spent much of the late 1960s and early 1970s fighting gentrification in Lincoln Park, allying with other organizations in Chicago to uplift minority and low-income communities, and rallying for an independent Puerto Rico.

Bobby Rush, former member of Congress, co-founder of the Illinois Black Panther Party and longtime friend of Jiménez, called him a “premier fighter” with a quiet demeanor who could move mountains — always for the oppressed — by simply speaking, even from a young age.

“Cha Cha never stopped working for ordinary people,” Rush told the Sun-Times on Saturday afternoon. “He made an absolutely unalterable commitment to protect the Puerto Rican community. He refused to let them be gentrified ... He made our society and our world better. Cha Cha was a beacon for us all.”

Mr. Jiménez’s family came to Chicago during a wave of Puerto Rican migration to the mainland around the time of Operation Bootstrap — a series of federal economic reforms launched in the mid-1940s to address economic crises on the island — and eventually settled in Lincoln Park.

José Cha Cha Jiménez speaks during a protest by the Young Lords and others after the fatal shooting of Manuel Ramos by a police officer in May 1969. Chicago Sun-Times archives

Along with several others, Mr. Jiménez — at the age of 11 years old — helped found the Young Lords street gang in 1959, said Felipe Hinojosa, a professor of history at Baylor University. He went on to become chairman in 1964.

But it was in 1968 that Mr. Jiménez transformed the gang into a movement for civil rights and fair housing. While serving a 60-day stint in jail for a drug charge that year, he read about the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Puerto Rican Independence Party member Pedro Albízu Campos while in solitary confinement. He later met Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton, and they discussed the divisions between Black and Puerto Rican Chicagoans and the similar work their two groups had been doing.

“I figured this is what we need in the Puerto Rican community, militant like the Black Panther Party to address the police brutality and housing issues we were facing,” Mr. Jiménez told WBEZ in 2018. “We brought the movement to include other people in the community. We built a movement from a gang.”

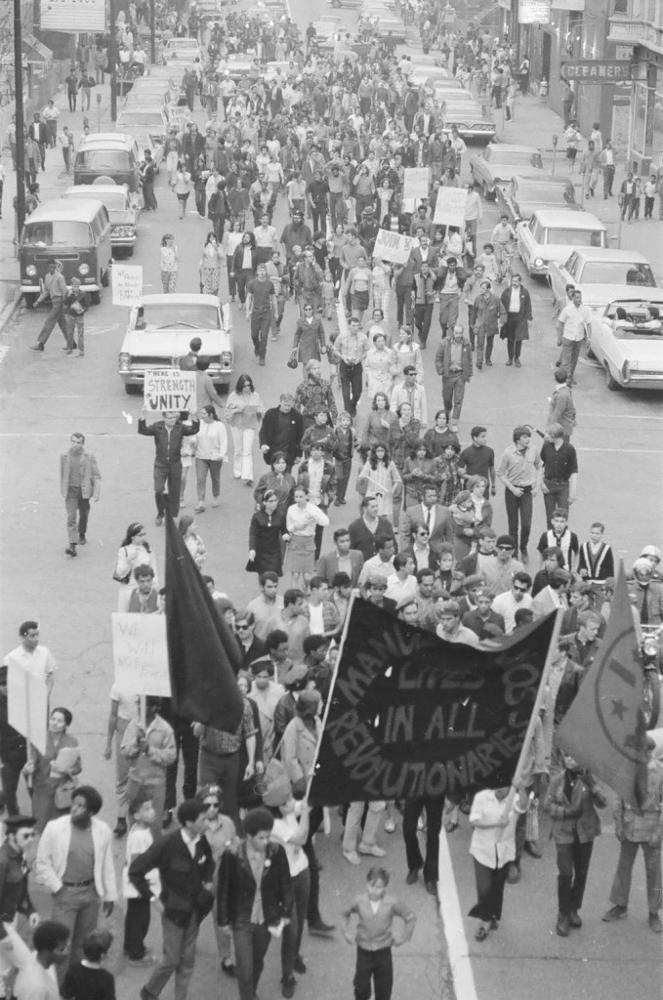

The Young Lords and others march from Armitage and Halsted to protest the fatal shooting of Manuel Ramos by an off-duty police officer in May 1969. Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum

Donning purple berets, the group organized several marches against police brutality in response to the killing of the Young Lords’ 20-year-old minister of defense Manuel Ramos, who was unarmed when he was fatally shot by an off-duty police officer May 4, 1969. The officer claimed self-defense against a gun that was never found. The group’s minister of education, Ralph Rivera, was shot in the head but survived.

Many of the Young Lords’ programs reflected similar successful Black Panther Party events: Free meals, free medical and dental clinics, and a free child care center, all in the basement of Armitage Avenue Methodist Church at 834 W. Armitage Ave. They occupied the building for four days to protest Chicago Department of Buildings orders to stop due to code violations.

The child care center allowed the group to welcome more women, individuals from all racial backgrounds and members of the LGBTQ+ community.

The group fought the Lincoln Park Conservation Association, which had been pushing to gentrify the area, and confronted landlords and real estate brokers. They also proposed plans for low-income housing in the neighborhood to the Department of Urban Renewal — ultimately losing out to the Lincoln Park Conservation Association’s plans for middle-income housing.

Omar López, the Young Lords’ minister of information, said Mr. Jiménez’s love for his community helped him stay true to his beliefs, and his strength in organizing came from how he could identify what was causing harm to his community — and uniting people against it.

“He chiseled a new image in the psyche of a whole generation of young people through his political analysis of the community,” Lopez, 80, said. “He really helped young men and women to find themselves as equals in political struggle … It was an added tool in our resistance.”

By June 1969, Mr. Jiménez and Hampton, along with members of the Young Patriots — a group of low-income white residents in Uptown who waved Confederate flags and wore buttons supporting the Black Panthers — formed the Rainbow Coalition to broaden the scope of their work.

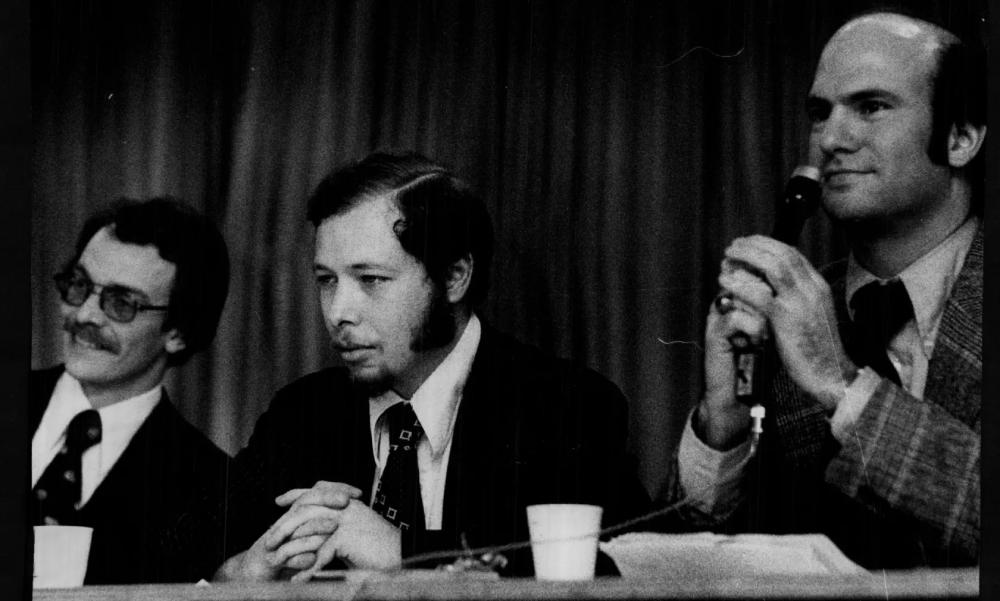

Bobby Rush, deputy defense minister of the Illinois Black Panther Party, reads a statement on June 4, 1969, during a news conference following an early morning raid on the Chicago Panther headquarters by FBI agents, who arrested eight people. Rush called the raid "... a trick ... to attack the party.” At left, José Cha Cha Jiménez, chairman of the Young Lords Organization, a Chicago-area Puerto Rican civil rights group. WBEZ

“It was a group of people fighting side by side in an alliance for change,” Mr. Jiménez told WBEZ in 2018. “But we were in conflict with [Mayor Richard J. Daley and city officials] because we lived in prime real estate areas.

“It’s not as racial, it’s more economic … it’s not just a housing issue, they were taking away our voice. There was a lot of repression going on.”

Rush said coming together under the single banner saved the groups, and that it was their unity that made them so effective, inspiring other progressive movements.

“We were the genesis,” Rush said. “The Rainbow Coalition saved us. We were able to create peace and unity and love and respect out of that chaos for each other because we were willing to work together … It takes all of us to really make a difference

A New York chapter of the Young Lords Organization was established in late 1969 and made national headlines with its demonstrations.

Republican Darrell Quinley, (left), José Cha Cha Jiménez (center), and incumbent Ald. Chris Cohen ran for alderperson in the 46th Ward on Feb. 13, 1975. Sun-Times file

Rev. Jesse Jackson, founder of Operation PUSH and later the National Rainbow Coalition — a group that grew out of Jackson’s 1984 presidential bid and a nod to the group Jiménez and Hampton co-founded — merged the two groups in 1996 to make Rainbow PUSH, which remains headquartered in Chicago.

Mr. Jiménez evaded police for 27 months in the theft of lumber from a construction site that the group used to make repairs to their building. He served a year in jail. Spurred by the December 1969 killing of Hampton, Mr. Jiménez ran for 46th Ward alderperson, garnering almost 40% of the vote in his 1975 bid.

In 1983, he helped Harold Washington win the mayoral election before leaving Chicago.

“The Young Lords Organization turned political because we found out that just giving gifts wasn’t going to help our people; we had to deal with the system that was messing them over,” Mr. Jiménez said.

José “Cha Cha” Jiménez, a fugitive for 27 months, surrenders to police Dec. 6, 1972, at the Town Hall station at Addison and Halsted. He was being sought in the theft of lumber that was used to make repairs on the Young Lords’ building. He served a year in prison. Sun-Times file.

Mr. Jiménez, who struggled with heroin addiction as a young man, also worked as a youth gang and addiction counselor in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he continued to be vocal about the fight against gentrification.

“We didn’t start this movement, and we didn’t finish it, but we definitely contributed to it, and that’s our victory,” Mr. Jiménez told WBEZ in 2018. “COINTELPRO and organizations like that want to keep us disunited, so our first mission is to unite our people and go from there ... Individuals can’t make any change, you have to do it united.” COINTELPRO was an FBI program that infiltrated and surveilled political groups thought to be subversive.

“What we need now is a victory,” José Cha Cha Jiménez says in a May 3, 1973, interview. Howard D. Simmons/Sun-Times archives

After his health declined, Mr. Jiménez returned to Chicago, where he helped foster a new generation of Young Lords, Lopez said.

“He was just a human being with a lot of strength,” Lopez said. “He was able to share some of that with the new era of Young Lords. They followed his lead up until the end.”

He is survived by his three sisters, five children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Violet Miller is a general assignment reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times after starting as an intern and later a freelancer. She was previously a breaking news correspondent for The Daily Herald.

Winner of eight Pulitzer Prizes, the Chicago Sun-Times was founded in 1948 through a merger of the Chicago Sun and the Daily Times. It’s known for hard-hitting investigative reporting, in-depth political coverage, timely behind-the-scenes sports analysis and insightful entertainment and cultural coverage. In 2022, it became part of the Chicago Public Media family of companies and now operates as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.