It Wasn’t Just Flawed Forecasts, Dishonesty Has Also Hurt Economists

Ben Casselman has an interesting piece in the New York Times about how economists have lost standing with both politicians and the public at large. While he attributes the profession’s problem to flawed forecasts and arcane language, I would argue the problems go much deeper.

There has been a major lack of honesty in important areas that have had a huge impact on people’s lives. The two areas I would highlight are trade and the bailouts in the financial crisis.

The Trade Coverup

The story with trade runs deep. As Casselman tells us, economists all like to claim that they are proponents of “free trade.” But there are two points here that economists tend to give short-shrift or no shrift.

The first is that trade has losers. That is not left-wing jargon, that is basic economic theory. Paul Samuelson, arguably the country’s most influential economist ever, co-authored a famous piece on trade theory making this point more than eighty years ago.

In this piece, Samuelson made the case that in a country with a large amount of skilled labor (e.g. college-educated) relative to the rest of the world, and a small amount of less-skilled labor (non-college educated), less-skilled workers would be hurt by an opening of trade with developing countries. In other words, the loss of jobs and the downward pressure on the wages of manufacturing workers was not an unfortunate side-effect of recent trade deals, it was the point.

While economists will occasionally acknowledge the fact that there are losers, they usually imply that this group is a small number of people who can easily be made whole with a limited amount of adjustment assistance. In reality, we are talking about millions of workers who actually lost their jobs and tens of millions more who saw lower wages.

There are two simple graphs that display this handwaving by economists beautifully. The first is a graph showing the share of manufacturing workers in total employment. As can be seen there is a downward trend in the whole period from 1970, nothing special to see as the trade deficit exploded in the first decade of this century.

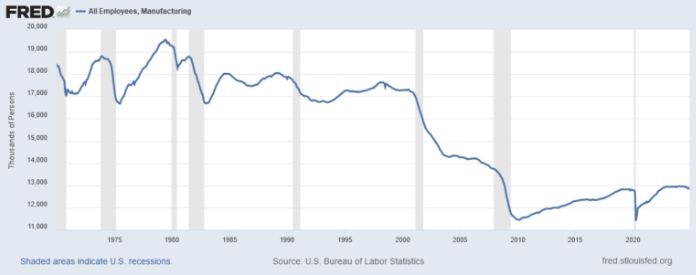

The second graph shows a slightly different picture. It’s total manufacturing employment since 1970. In this graph we see cyclical ups and downs but relatively little change from 1970 to 1998. Then from the middle of 1998 to December of 2007 the economy lost almost 4 million manufacturing jobs, more than 20 percent of total employment. This is the period where the trade deficit exploded reaching a peak of almost 6 percent of GDP in 2006. (Note this is before the Great Recession.)

Economists are less anxious to talk about this graph. When they do, they will generally say that the job loss was due to productivity growth and not trade.

This line should get anyone fighting mad. They want us to believe that productivity growth cost us large numbers of jobs, coincidentally just when the trade deficit was exploding, but not in the decades before or the decades after?

It’s fair to acknowledge that there have been benefits from trade. We can buy all sorts of goods at much lower prices because we import them from China and other developing countries, but it is just dishonest to try to deny there has been a huge cost to millions of workers. (Note: this effect is not reversible, contrary to what you hear from some prominent politicians.)

That may sound bad, but it actually gets much worse. While the line is “free trade,” the reality is quite different. Our doctors get paid more than twice as much on average as doctors in other rich countries, pocketing more than $350 thousand a year. If we got our doctors’ pay down to the average in places like France and Germany it would save us more than $100 billion a year in medical expenses ($1000 per family per year).

This gap in pay persists because our “free traders” apparently had little interest in promoting free trade in physicians’ services or the services of other highly paid professionals. The agenda was selective free trade. Free trade in manufactured goods, which had the predicted and actual effect of driving down the pay of manufacturing workers and non-college educated workers more generally, but preserving the protectionists barriers that sustained the high pay of highly educated workers.

But wait, it gets worse. A major part of all the trade deals negotiated in the last four decades was longer and stronger patent and copyright protections, both for the United States and our trading partners. Patents and copyrights are government-granted monopolies, the complete opposite of free trade. How are these restrictions included in “free trade” agreements?

And there is a huge amount of money at stake. We will pay more than $650 billion this year for prescription drugs and other pharmaceutical products. We would likely pay around $150 billion if these items were sold in a free market without patent monopolies. The difference of $500 billion comes to around $4,000 per family per year. If we add in the cost of patent and copyright monopolies in other areas it is almost certainly well over $1 trillion a year.

These monopolies also make some people very rich. Bill Gates has agreed to be the poster child for this point. Needless to say, most of the beneficiaries are not among the less-educated.

To be clear, patents and copyrights, like all forms of protectionism, serve a purpose. They provide an incentive for innovation and creative work. But they are clearly not free trade and in any case, there are arguable better and cheaper ways to provide these incentives. But when we bless these monopolies as free trade, it is hard to even discuss alternatives.

The Second Great Depression Myth and the Bank Bailouts

After the collapse of the housing bubble the country faced its largest financial crisis since the Great Depression. Most of the country’s major banks were looking at bankruptcy. At this point, rather than letting the free market work its magic, the vast majority of the country’s leading economists were insisting that the government needed to bail out the banks. The alternative would be a Second Great Depression.

This was a lie. There is little doubt that the recession would have been worse if we allowed the chain of bank collapses to continue, but how would this condemn us to a Second Great Depression, a decade of double-digit unemployment?

Having dealt with the first Great Depression, we now know the secret for getting out of a depression: spend money. If the chain of bank collapses had continued the vast majority of people would have the vast majority of their bank accounts kept whole by the FDIC, taking care of the immediate problem of paying their bills.

To reboot the economy, we just would need a large-scale stimulus package, think three or four 2009 Obama stimulus packages. This could take any form. We could spend more on things like health care, climate, and infrastructure or we could just send everyone $5,000 checks. To make Republicans happy, we could even put Donald Trump’s name on the checks.

It is reasonable to argue that there would have been political obstacles to this sort of massive stimulus program. That is certainly possible, but that is a very different argument than saying the economics of a major bank collapse condemned us to a Second Great Depression. Rather this would be a case of economists making predictions about politics.

It is also worth noting the large potential gains from a collapse of our major banks. We would have instantly downsized our incredibly bloated financial system, eliminating a huge amount of waste. This financial system is also the source of many of the country’s great fortunes. Again, economists were being dishonest in a way that benefited the rich.

The Economists’ Missed Calls

I won’t go into great lengths on the big misses of the last two decades. Failing to see the housing bubble and the wreckage that it would cause is to my mind a disastrous failure. We had an unprecedented run-up in nationwide housing prices at a time when rents were moving roughly in step with overall inflation. And the flood of dubious loans was hardly a secret, the industry was bragging about it.

It also should not have been hard to recognize the bubble was driving the economy. Residential construction is ordinarily around 3.5 percent of GDP. It peaked at almost 6.0 percent in 2005. What would replace 2.5 percent of GDP in annual demand ($700 billion in today’s economy) if the bubble burst. And the bubble was also driving consumption as people were borrowing against their bubble generated home equity.

In short, missing the bubble and the consequences of its collapse was a pretty huge mess-up. And of course, almost no economists faced any career consequences for this mistake. Everyone got a collective “who could have known?” amnesty.

The other big miss was failing to recognize how persistent the pandemic inflation would be. I am more sympathetic to this error, probably in part because I was a card-carrying member of Team Transitory.

There is no doubt that inflation was more persistent than I and many others expected, but there were two major non-economic events that I at least did not anticipate. I was expecting that the pandemic would quickly be brought under control as most of this country and the world got vaccinated. I did not anticipate that there would be two further major waves (the delta strain and the omicron strain) which would lead to large-scale shutdowns both in the United States and elsewhere in the world.

I also didn’t anticipate Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the economic disruptions that followed. Would inflation have been more persistent than I originally expected in the absence of these events? Perhaps, but I don’t think it’s unreasonable to get at least a partial amnesty for not having foreseen these disasters.

When It Comes to Economists, the Angry Masses Have a Case

I realize and share the frustration of many economists when the public fails to understand simple economic principles. For example, I think a carbon tax, with a rebate for low and moderate-income households, is a great idea, but I recognize the politics are totally toxic. The understanding of a progressive marginal income tax is incredibly weak. Many people cannot conceptualize that raising Elon Musk’s taxes does not mean raising their taxes.

But economists have seriously failed the public in important areas over the last three decades. And these failures played a role in fostering the upward redistribution of income over the last four decades. People have a right to be angry.

Dean Baker co-founded CEPR in 1999. His areas of research include housing and macroeconomics, intellectual property, Social Security, Medicare and European labor markets. He is the author of several books, including Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer. His blog, “Beat the Press,” provides commentary on economic reporting. He received his B.A. from Swarthmore College and his Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Michigan.

His analyses have appeared in many major publications, including the Atlantic Monthly, the Washington Post, the London Financial Times, and the New York Daily News.

The Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) was established in 1999 to promote democratic debate on the most important economic and social issues that affect people’s lives. In order for citizens to effectively exercise their voices in a democracy, they should be informed about the problems and choices that they face. CEPR is committed to presenting issues in an accurate and understandable manner, so that the public is better prepared to choose among the various policy options.

Toward this end, CEPR conducts both professional research and public education. The professional research is oriented towards filling important gaps in the understanding of particular economic and social problems, or the impact of specific policies. The public education portion of CEPR’s mission is to present the findings of professional research, both by CEPR and others, in a manner that allows broad segments of the public to know exactly what is at stake in major policy debates. An informed public should be able to choose policies that lead to improving quality of life, both for people within the United States and around the world.

CEPR was co-founded by economists Dean Baker and Mark Weisbrot. Our Advisory Board includes Nobel Laureate economists Joseph Stiglitz; Janet Gornick, Professor at the CUNY Graduate School and Director of the Luxembourg Income Study; and Richard Freeman, Professor of Economics at Harvard University.

IFPTE, Local 70

Employees at CEPR are members of the nonprofit professional employees union IFPTE Local 70. For more information on the union and other organizations belonging to Local 70, visit NPEU.org.