Ten Questions & Answers on Measles Protection

With measles cases rising across the country, I’ve been getting a lot of questions (especially after that Hannity interview yesterday)! Here are your top 10 answered.

TL;DR: MMR vaccines are highly effective and provide long-lasting protection. Outbreaks occur mainly among unvaccinated individuals.

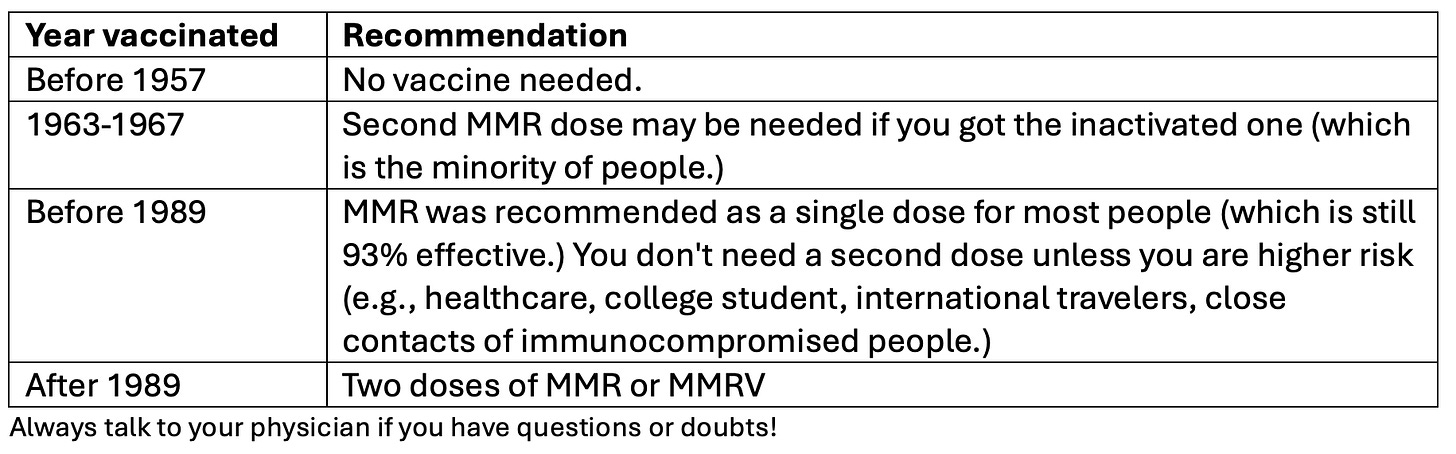

1. What is “up-to-date” on the measles vaccine? Do I need a booster?

You’re considered up to date if you:

-

Have two doses of MMR or MMRV

-

Were born before 1957 (since measles was widespread then, most people were naturally exposed and are assumed immune)

You’re very well-protected (97% effective against measles) and do not need a booster.

An exception: If you received the inactivated measles vaccine between 1963 and 1967, you may need a booster. Most people at that time received the more effective live vaccine, but if you’re unsure, check with your healthcare provider.

Table by YLE

Measles antibodies last a long time. Studies tracking individuals for 17 years found that most (~91%) still had protective antibodies. Modeling studies estimate a single dose of MMR provides protection for about 25 years—and we get two doses, extending immunity even further. Scientists estimate that measles antibodies have an astonishing half-life of over 3,000 years. We also have T cells and B cells (see more in #2).

Our recommendations may evolve in the future, but for now, the data remain strong. One reason they could change is that with lower measles exposure, our immune systems no longer receive periodic boosts from asymptomatic infections—similar to how hybrid immunity works with Covid-19. Only time will tell.

2. Should I check my titers? Does that help?

Titers measure antibodies in your blood but don’t account for T cell and B cell immunity, which also protect you.

T cell and B cell memory are particularly important because once measles enters your body, it doesn’t replicate that fast. It is slow enough that if you get infected, they will start pumping out antibodies to prevent you from getting sick. This means that a negative result on titers does not necessarily mean you are not protected.

The main reason to get titers would be as a matter of insurance coverage for a booster-—some plans won’t cover the cost unless titers to one of the MMR viruses come back negative.

Titers could also be useful for pregnant women (see more in #6).

3. Is there a reason NOT to get a booster for measles?

Getting a booster has very few risks.

However, unnecessary boosters could contribute to a vaccine shortage. As explained here, 12 million doses are available in the country each year; we must reserve these for children since they need at least two for initial protection. This has to be the priority. Local shortages in Texas have already been reported. Canada ran short last year.

4. Why do we need just two measles vaccines when we are young but an annual flu shot, for example?

They are just very different viruses, so tools like vaccines work differently:

-

Mutate differently. Measles mutates far less than flu. The measles virus from the 1960s is virtually the same today, unlike flu, which changes every couple months. (See this previous YLE post for more.)

-

Infect differently. Measles replicates slowly and deep in the body, giving the immune system time to act. Flu replicates quickly in the nasal passages, making it harder for the body to stop transmission.

5. Is infection-induced immunity better than vaccine-induced immunity?

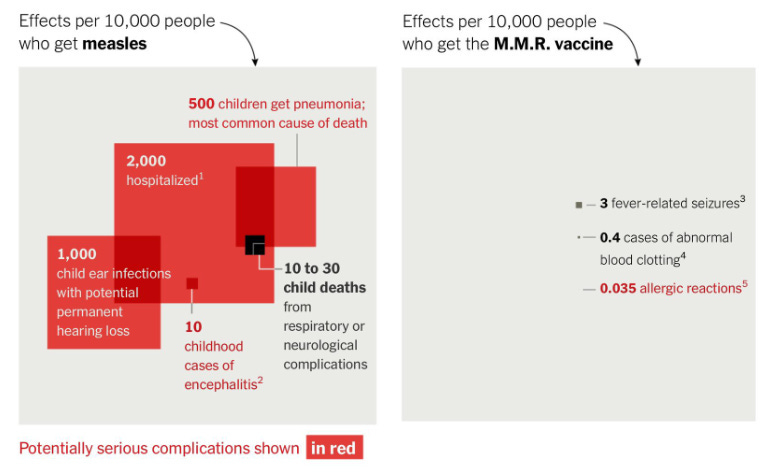

Infection-induced immunity may last slightly longer, but at a high cost—measles can lead to severe complications, including pneumonia, encephalitis, and death.

The vaccine also offers strong, long-lasting protection. It’s a live virus vaccine, so it’s a tiny, controlled version of the infection for all intents and purposes—but with far fewer risks. If I were to bet on it, I would rather have the odds on the right than the left.

Source: New York Times

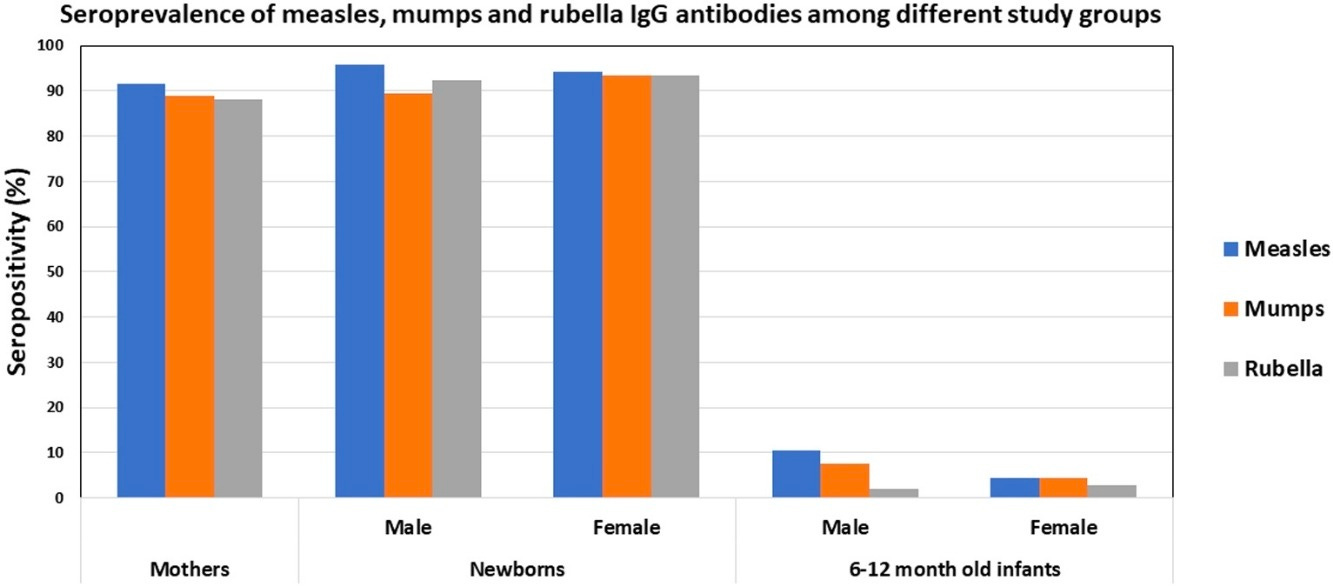

6. Is a baby protected if their mom was fully vaccinated?

The vast majority of moms transfer antibodies to their fetuses. (Moms’ bodies are pretty amazing!) Once born, antibodies wane quickly and are almost all gone at 6-12 months of age.

Source; International Journal of Infectious Diseases

Breastfeeding may provide some protection, but it is not a substitute for vaccination. The role of breastmilk antibodies in the protection from measles is possible, but there is a lack of robust supporting evidence.

Anyone trying to conceive should have MMR titers checked, and if levels are low, MMR should be administered 28 or more days before conception.

7. Why wait until 12 months to get children vaccinated?

We try to find the sweet spot by balancing a few factors:

-

Maternal antibodies waning

-

Maturity of the immune system

-

The most common age of infection

That said, if there is a measles outbreak, young children need protection as soon as possible. Early vaccination is one provisional measure we can take starting at 6 months. This early dose does not count toward the two-dose series, which will be needed at 12 months.

8. Can I get measles if I’m fully vaccinated?

The MMR vaccine works incredibly well—you’re 35 times less likely to get measles than someone with no immunity.

However, no vaccine is perfect. A breakthrough case is rare but possible (3 out of 100 fully vaccinated people will get infected), but the illness is typically mild.

We don’t know why there are breakthrough cases, but there are two possibilities:

-

Waning immunity, or

-

Vaccine didn’t work in the first place for whatever reason. ~7% of people do not get protection after the first dose, but, of those, 95% will be fully protected after a second dose. Only a small percentage of people don’t respond to both doses.

9. If I am exposed, can I transmit measles?

Transmission after vaccination, especially if you’re asymptomatic, is rare:

-

We see this in the lab data. A small study found no viral shedding among asymptomatic or mildly ill patients. However, this is a very old study, and we need to replicate its findings with more sensitive lab equipment.

-

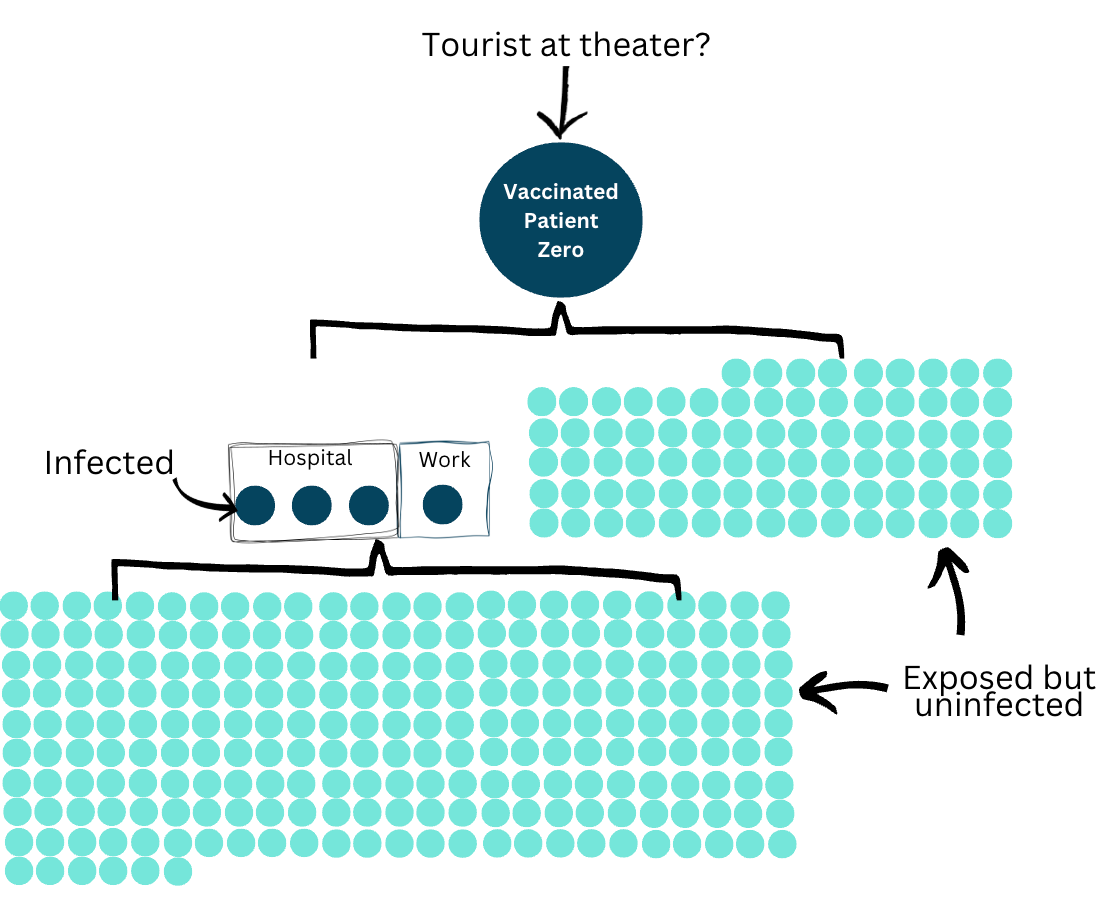

We see this in the epidemiological data. While several studies show spread among vaccinated people, especially after intense or prolonged exposure, it’s limited.

A 2011 New York outbreak was the first documented case of a fully vaccinated person spreading measles. Out of 88 close contacts, only 4 got infected—and none of their contacts got sick. We would have expected a ~90% infection rate if this had been an unvaccinated case.

Source: YLE

10. Do we have to wait for my child to be 4 years old for a second MMR dose?

The second MMR dose can be given 28 days after the first—unless it’s the MMRV vaccine, which requires a 3-month gap.

This flexibility is especially useful in outbreak areas. Healthcare providers may recommend a second dose earlier for children aged 1 to 4 who live in or are visiting outbreak areas.

Longer intervals between doses generally strengthens immunity, making some worry that shortening the measles vaccine interval could weaken protection. However, data suggest timing isn’t a major factor in long-term immunity, as long as the first dose doesn’t interfere with the second (requiring at least 4 weeks between them).

The second dose, typically given at ages 4-6, ensures protection before school, where measles spreads easily. It’s not technically a booster, but it helps cover the 7% of people who don’t respond to the first dose. Without it, gaps in immunity can fuel outbreaks.

Bottom line

If you’re fully vaccinated, you can be confident in your protection. We continue to follow the data, but failure to vaccinate still plays the biggest role in measles in the United States compared to vaccine failures.

If you have specific questions, be sure to bring them up with your physician.

Love, YLE

Big thanks to Edward Nirenburg and Dr. David Higgins for helping me wade through a lot of this science and recommendations.

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. Dr. Jetelina is also a senior scientific consultant to a number of non-profit organizations. YLE reaches over 340,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade.