Sunday Science: How Political Attacks Could Crush the mRNA Vaccine Revolution

The day after Donald Trump moved back into the White House in January, he celebrated a US$500-billion private-sector investment in artificial intelligence (AI) with a high-profile announcement in the Roosevelt Room. The new president looked on as technology billionaire Larry Ellison highlighted one of the initiative’s most transformative goals: using messenger RNA vaccines to transform cancer treatments.

By harnessing AI to analyse tumour genetics, Ellison explained, researchers could rapidly design personalized vaccines tailored to an individual’s cancer. “This is the promise of AI and the promise of the future,” he said.

Biotechnology executives were elated. Trump had, just five years earlier, propelled mRNA medicines into the spotlight through his signature effort to fast-track the development of a coronavirus vaccine. Now, just one day into his second term, he was once again elevating the technology to the national stage.

“Then the bottom fell out,” says Deborah Day Barbara, co-founder of the Alliance for mRNA Medicines (AMM), a trade group representing more than 75 companies and academic institutions that are advancing mRNA research, development and manufacturing.

A prominent vaccine critic who had vilified the mRNA-based COVID-19 jabs, Robert F. Kennedy Jr, was appointed to lead the country’s top health agency, and long-time champions of immunization science in the civil-service sector were shown the door. Research grants tied to HIV prevention and pandemic preparedness were abruptly cancelled, including many involving mRNA. And numerous other projects that were focused on mRNA vaccine technology were compiled into a list, potentially signalling their impending termination.

At the same time, legislators in several states have been pushing to ban or restrict the use of mRNA-based medicines for infectious diseases. None of these measures has become law, but the efforts threaten to destabilize the mRNA industry, creating uncertainty and potentially limiting patient access to emerging treatments.

The anti-mRNA sentiment — coupled with the sweeping shake-up of science funding across the United States — has sparked fears that this once-celebrated technology, widely seen as a major engine of next-generation vaccines and therapeutics, could soon find itself on the chopping block.

For AMM executive director Clay Alspach, a principal at Leavitt Partners, a health-care consulting firm in Washington DC, the message has been unmistakable: “This is an existential threat,” he says.

By mid-March, the AMM was holding regular conference calls to strategize. Members swapped intelligence, compared notes on delayed grants and tried to anticipate what might come next. Amid the uncertainty, a few questions loomed large: how far would the clampdown on mRNA go? Would it stop at COVID-19 jabs? Would it extend to all vaccines in development for influenza and other infectious threats? Or reach even into mRNA-based drug therapies in the works for cancer, autoimmune disorders, rare genetic diseases and more?

From hero to zero

Five years ago, the US government was spending billions of dollars to support the development, manufacturing and roll-out of mRNA vaccines, which played a major part in curbing the COVID-19 pandemic. Pharmaceutical companies were pouring in capital and building ambitious pipelines centred on mRNA. The technology was feted with a Nobel prize. Investor confidence was sky-high.

Now, in the span of just a few months, the mood across the industry has grown darker — chilled by a newly hostile political climate.

One contract manufacturer of mRNA products has seen a substantial decline in business as government-backed vaccine programmes have their funding pulled, according to a senior company executive. Another biotech executive says that his mRNA-focused company is considering relocating planned clinical trials for anti-viral vaccines to outside the United States — or scrapping them entirely, shifting the firm’s focus to less politically volatile therapeutic areas. “It’s all just a commercial and regulatory risk now,” he says.

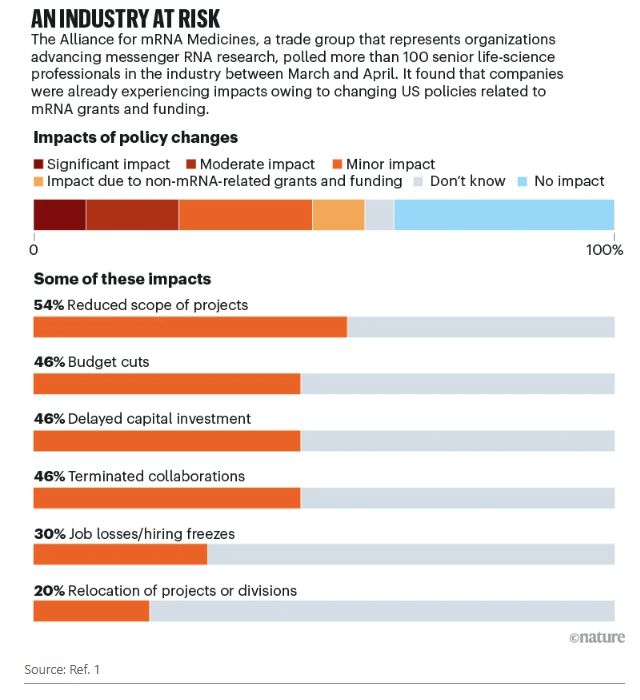

Both executives requested anonymity to avoid drawing political attention to their companies — but their experiences reflect a broad upheaval that is now rippling through the industry. In a survey released this month by the AMM, nearly half of 106 senior biotech and pharma executives reported direct impacts from US policy shifts this year — including project downsizing, budget cuts, delayed investments, terminated partnerships, job losses, hiring freezes and planned relocation of operations overseas1 (see ‘An industry at risk’).

Much of the current antipathy towards mRNA vaccines can be traced back to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the political and cultural backlash it left in its wake. Critics cite the compressed timelines and emergency use authorizations as signs that the safety of the vaccines was compromised. Vaccine mandates — imposed by governments, employers and schools — further fuelled resentment. Meanwhile, conspiracy theories about DNA alteration and population control continue to circulate widely online, deepening public mistrust and giving political traction to opposition against mRNA technology.

What began as fringe scepticism has increasingly entered the mainstream consciousness, amplified by partisan media and political figures who frame the vaccines not as public-health tools but as symbols of government overreach. Among the most prominent of these is Kennedy, now secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), who has long questioned the safety of childhood immunizations and built his political brand on vaccine resistance. (HHS officials did not respond to requests for comment. A spokesperson for the White House pointed to a public statement that did not address the questions posed by Nature.)

There are some conservative voices who are more supportive of mRNA technology — for example, a February report2 from the Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute, a public-policy organization in Austin, urges policymakers to recognize the technology’s broad potential in medicine and agriculture. But those views have been mostly drowned out by more extreme rhetoric.

Even the term ‘mRNA’ has become a political lightning rod; its charged connotations now influence scientific discourse and health policy far beyond the vaccine debate. “That paranoia has gotten wrapped into mRNA as a word,” says Jeff Coller, an RNA biologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, who is also involved in several small biotech firms.

Seeking to reframe the narrative, Coller and others are mobilizing around a strategic communications offensive, emphasizing mRNA’s potential not just in thwarting infectious threats but also in treating many of the same chronic conditions targeted by Kennedy’s ‘Make America Healthy Again’ initiative. The campaign to rehabilitate mRNA’s reputation starts at the top: with appeals to Trump’s legacy as a champion of medical innovation.

Legacy on the line

AMM leaders are preparing to publish a series of editorials that make the case that Trump’s decisive leadership during Operation Warp Speed — the 2020 programme that delivered COVID-19 vaccines in record time — marked the beginning of a new chapter in biotechnology and positioned the United States at the forefront of what many see as the fourth great wave of pharmaceutical innovation, after small-molecule drugs, biologics and cell and gene therapies.

Framing it as a chance for Trump to cement his place in medical history, they are urging the president to build on the foundation that he helped to lay. In particular, they pointed out that, by supporting mRNA-based cancer treatments, he could achieve a major unmet goal that was advanced by his predecessor Joe Biden, who had made “ending cancer as we know it” a signature priority. Trump “could be the president who is a true visionary on cancer”, says Coller, a leading academic voice at the AMM.

People queue for COVID-19 vaccinations in Washington DC.Credit: Jim Watson/AFP via Getty

Such messaging just might resonate. Although Trump criticized the roll-out and mandates surrounding the COVID-19 vaccines in the period between his two terms, allies say he remains proud of the part he played in accelerating the technology’s development. “President Trump believes that Operation Warp Speed was a roaring success, and that the COVID mRNA vaccines were his great achievements,” says Robert Malone, a scientist involved in foundational mRNA research and a high-profile voice in conservative-leaning health-policy circles.

But leading the charge against mRNA technology are individuals in the ‘medical freedom movement’ — Kennedy chief among them. They contend that COVID-19 vaccines were rushed through approval without adequate long-term testing, alleging that safety corners were cut in the name of speed, and that the risks of mRNA platforms continue to be deliberately downplayed.

At his confirmation hearing earlier this year, for example, Kennedy — who previously described an mRNA-based COVID-19 jab as the “deadliest vaccine ever made” — persisted in claiming that the vaccine was recommended for young children “without any scientific basis”, despite published clinical-trial evidence3 to the contrary.

Public-health researchers and vaccine scientists emphasize that mRNA vaccines have consistently demonstrated robust safety and effectiveness in preventing severe COVID-19 outcomes, supported by extensive data from rigorous clinical trials and real-world studies. Yet, with trust in institutions and in the biomedical establishment crumbling, some argue that pulling back from mRNA is the only responsible course of action — not because the science is flawed, but because the damage to public confidence is too deep.

“If mRNA has a chance to have impact in the future, there needs to be a restoration of public trust around it,” says David Mansdoerfer, a political consultant in Fort Worth, Texas, and a former senior HHS official in the first Trump administration. To that end, he, like many associated with Kennedy, would support federal regulators withdrawing approval for all COVID-19 vaccines that initially entered the market under emergency-use provisions — including the mRNA-based ones that later won full approval. Mansdoerfer advocates re-evaluating the jabs under a standard review process.

‘The brand is damaged’

The problem of mRNA’s reputation isn’t just a communications challenge — it’s a systemic liability. “I fear the brand is damaged for most uses,” wrote Vinay Prasad, a haematologist–oncologist at the University of California, San Francisco, in a Substack post in March. A vocal critic of COVID-19 vaccine mandates under Biden, Prasad was selected this month to lead the division of the US Food and Drug Administration that oversees vaccines and other biological products.

The branding issue for mRNA is not just a problem in the United States either. An analysis of social-media data across 44 countries, published last year, found “widespread negative sentiment and a global lack of confidence in the safety, effectiveness and trustworthiness of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics”4.

Nor is the problem confined to the two most prominent mRNA vaccines — those from the biotechnology company Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a collaboration between pharmaceutical firms Pfizer in New York City and BioNTech in Mainz, Germany — both developed at record speed in late 2020 and since administered to billions of people worldwide. New concerns have surfaced regarding next-generation jabs, including one from Arcturus Therapeutics in San Diego, California.

This ‘self-amplifying’ COVID-19 vaccine, now approved in Japan and Europe, is designed to replicate itself inside cells, allowing for lower doses with fewer side effects. But in Japan, where the vaccine has been available the longest, misinformation has fuelled fears that its components could be transmitted from vaccinated individuals to others, with some rhetoric likening the shot to a ‘third atomic bomb’.

Notably, however — unlike in the United States, where the pushback has penetrated policymaking spheres — the leading authorities in Japan have continued to champion the technology. Earlier this year, for example, the Japanese government authorized further domestic manufacturing sites to expand production of the self-amplifying jab — and Joseph Payne, president and chief executive of Arcturus, says there is similar support from other governments around the world.

The uniqueness of the US retreat raises an unsettling prospect for the scientists and entrepreneurs who launched the mRNA revolution from US laboratories and start-up companies: the future of the technology might unfold elsewhere. Currently, around two-thirds of the mRNA industry’s jobs are based in the United States, according to the AMM. Yet, if current trends persist, a substantial portion of these positions could be lost or relocated overseas. “I think what we’ll see in the next few years is that this tech is ceded to international competitors,” says Alex Wesselhoeft, who directs RNA therapeutics at the Mass General Brigham Gene and Cell Therapy Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Rewriting the script

Aiming to retain global leadership, many researchers in the mRNA sector in the United States are rethinking how to present their innovations — starting with stepping away from the term ‘vaccine’, particularly when describing mRNA-based cancer treatments. Although these therapies work like vaccines, delivering genetic instructions to produce proteins that train the immune system, they are designed to treat disease, not prevent it — hence the industry’s pivot towards labels such as ‘immune therapy’.

Ellison, in his January remarks at the White House, still used the legacy terminology of ‘vaccine’ in this context, but companies, including Moderna, are shifting their language. Last month, Moderna — which not only makes one of the world’s leading COVID-19 vaccines but is also a front runner in personalized cancer therapy — updated the product pipeline on its website, replacing ‘cancer vaccines and therapeutics’ with the more neutral label ‘oncology’.

Other companies with diversified mRNA portfolios are also recalibrating their messaging, highlighting opportunities for delivering therapeutic proteins inside the body or components for gene editing to reprogram cells, while downplaying associations with vaccines where possible. Arcturus, for example, is advancing two mRNA-based treatments for rare genetic disorders, with preliminary data from mid-stage clinical trials expected in the coming weeks. According to Payne, “We’ll be speaking more toward our therapeutic programmes, just because those don’t have the same market-based headwinds that our vaccine enterprise does.”

“But that doesn’t mean we’re stopping the vaccine efforts at all,” he says. Case in point: earlier this year, Arcturus completed enrolment for a 200-person trial, funded by the US government, to evaluate a self-amplifying mRNA candidate to prevent infection with H5N1 influenza, with results expected later this year. Whether that support will extend beyond the current study, however, remains unclear.

Equally unclear — for the entire mRNA sector — are the long-term financial prospects, regulatory pathways and the willingness of governments to stand by a platform they once championed. It doesn’t help that the broader biotech industry is still grappling with a prolonged funding downturn, marked by sluggish capital markets, risk-averse investors and waves of layoffs across the sector.

Politics aside, raising money for an early-stage mRNA company to advance promising therapies through clinical trials was already an uphill struggle, notes Ipsita Smolinski, the founder and managing director of Capitol Street, a health-policy consultancy firm in Washington DC. “It’s ugly out there,” she says.

Still, many people in the field think the long-term prospects for mRNA technology remain strong — especially as applications in oncology and other areas begin to bear fruit.

“This is clearly a rough time,” says vaccine scientist Philip Dormitzer, who helped to develop the mRNA COVID-19 jab at Pfizer and is now based in Canada, where he consults for vaccine makers. “I don’t want to underestimate the real damage that’s been done — it is big.” But between the industry’s coordinated counteroffensive against misinformation and policy threats, and the sustained global momentum behind mRNA innovation, he expects science and public health to prevail.

That long view is key, says Payne. “Politics and policies come and go,” he says, “but science always will stand true.”

Nature 641, 580-582 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-01462-9

References

-

Alliance for mRNA Medicines. The mRNA Innovation Ecosystem (U.S.) A National Assessment Of Economic Impact, Therapeutic Potential, And Policy Implications (AMM, 2025).

-

Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute. Into the Spotlight: mRNA Technology, after Decades of Development, Is Poised to Reshape Medicine (TCCRI, 2025).

-

Walter, E. B. et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 35–46 (2022).

-

Xu, J., Wu, Z., Wass, L., Larson, H. J. & Lin, L. NPJ Vaccines 9, 218 (2024).

Elie Dolgin is a science journalist who splits his time between rural Vermont and urban Massachusetts. He holds a bachelor's degree in biology from McGill University and a PhD in evolutionary genetics from the University of Edinburgh. A former news editor at STAT, Nature Medicine and The Scientist, Elie has also written for publications including the New York Times, Newsweek and Science magazine.

His 2021 feature article for Nature, "The tangled history of mRNA vaccines," gained significant recognition and was referenced widely in the scientific literature, in national newspaper stories and by award selection committees.

Nature is a weekly international journal publishing the finest peer-reviewed research in all fields of science and technology on the basis of its originality, importance, interdisciplinary interest, timeliness, accessibility, elegance and surprising conclusions. Nature also provides rapid, authoritative, insightful and arresting news and interpretation of topical and coming trends affecting science, scientists and the wider public. Nature's mission statement: First, to serve scientists through prompt publication of significant advances in any branch of science, and to provide a forum for the reporting and discussion of news and issues concerning science. Second, to ensure that the results of science are rapidly disseminated to the public throughout the world, in a fashion that conveys their significance for knowledge, culture and daily life.

The Importance of Caring about the Truth

Ethan Siegel

Big Think (Starts With A Bang)

You don’t need to be a scientist or a philosopher for facts, reality, and the truth to matter. The alternative is simply known as bullshit.

April 23, 2025