Bullets in the Windows

On Friday, my phone lit up with urgent texts. First: gunshots, lockdown. Then the photos—bullet holes punched through windows, shell casings scattered across the floor, videos echoing with “pop pop pop.”

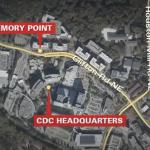

The CDC campus was under attack. Dozens of my friends and colleagues were inside.

I’ve spent the past 36 hours trying to process what happened. What is clear is this: it wasn’t random. Violence rarely is. And it goes far beyond what happened Friday.

The perpetrator was shooting at public health workers—the people who devote their careers to keeping communities safe. The ones who work to stop the spread of disease and reduce gun violence. And in this case, targeted because of their work on the Covid-19 vaccine.

Bullets struck four buildings. Some with more than 50 holes in the glass. The hardest-hit area was the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD) and the Immunization Safety Office (ISO). These are people who have carried a lot of the weight of the pandemic, endured relentless hostility, and have faced six months of attacks on vaccine policy. Many have almost no reserves left. And now, on top of everything, they were literally under fire.

Those bullet holes are a haunting, terrible metaphor for what public health has endured over the past six months—and the past six years.

We’ve endured doxxing, hacking, strangers at our homes, death threats in our inboxes, croissants thrown at us in coffee shops. Installing a new security system just because we volunteer for something or show up on TV. Wearing heart monitors because our cortisol levels have started impacting our organs. Deciding not to put our kids in daycare at the CDC campus because it may be targeted. Then firings. Defunding. Politically charged and targeted rhetoric.

And now a shooting happened. It could have been much worse if it weren’t for a police officer—who left behind three kids of his own—making the ultimate sacrifice. This doesn’t make it any less scary.

One question keeps coming up from colleagues in my text messages: Why do we keep doing this?

I know why. Because people in public health care too much about our country to stop. Because we care about our kids’ futures. Because we believe in a better life. Better community. Better health. We will serve our neighbors even if they don’t understand what we’re doing or why it matters. It’s in the blood of public health workers, woven into every late night, every hard decision, every moment we choose service over family or safety, whether it’s running into an Ebola outbreak or writing a policy brief.

In the next week, the glass will be patched, the windows replaced, the bullets swept from the floor. And this story (which has barely made the news) will vanish. But the trauma, the fear, the exhaustion will remain.

We’ll go back to our desks, our meetings, our spreadsheets. We’ll keep working to stop the spread of disease. We’ll keep working to prevent the next shooting. We’ll keep working for communities that may never know our names.

And we’ll do it knowing we were targeted simply for doing our jobs, jobs that protect even the people who hate us.

But make no mistake: this cannot be the cost of caring. We need more than patched glass. We need a country that values the people who protect it, recognizes the importance of words and their real-world consequences, and values community and neighbors, not just self. Now. Before the next shot is fired.

For my colleagues in public health

For those who feel shut down, disconnected, or even resentful that people expect you to keep showing up with empathy when you’ve been under attack for so long, it’s time to pause to name what’s happening. Acknowledge the shock and grief. Because if not, we risk getting stuck there. Processing it together is one way to move forward without carrying the weight alone. That doesn’t mean having all the answers. It means giving ourselves and each other the space to feel it, to say it out loud, to step back when needed. It’s okay to not be okay.

Over these past six years, I’ve learned that the loudest voices are not the majority, even though it feels like hell that they are. It’s also clear that the path is long, and I fear it’s going to get harder before it gets better. But, as MLK Jr. said: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Don’t let the darkness erase the stars, the sunset, the good that still exists. We need your light in the world.

And as a CDC friend texted me last night: Illegitimi non carborundum.

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. Dr. Jetelina is also a senior scientific consultant to a number of non-profit organizations. YLE reaches over 340,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, subscribe or upgrade.