How Bad Slavery Was

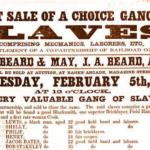

Last week, in a post on Truth Social, Donald Trump took the Smithsonian’s museums to task for emphasizing “how bad slavery was.” The White House staff followed up on August 21 with a statement titled “President Trump Is Right About the Smithsonian,” flagging several objectionable exhibits, including one, weirdly, on Anthony Fauci.

Trump is in eminent company. For nearly a century, between the 1860s and the 1950s, defenders of slavery succeeded in creating a dominant narrative in the nation’s textbooks, trying to show that slavery wasn’t so bad and that the real outrage was the abbreviated period of Reconstruction.

The whitewashing of slavery began as early as 1867, with publication of a book by Edward Pollard, titled The Lost Cause. In this account, slavery was mostly a benign system that uplifted Blacks; plantation owners were typically kindly. This echoed a century of antebellum Southern propaganda. Pollard contended that the Civil War was not really about slavery; it was a war over states’ rights.

As public education systems became more widespread in the South after the Civil War, states of the former Confederacy set standards to ensure that textbooks for public schools would portray a sympathetic view. These laws influenced Northern publishers. Meanwhile, some prominent Northern scholars embraced the Lost Cause view. The most notable of these was William Archibald Dunning of Columbia University.

Dunning became the leader of what became known as the Dunning School of studies on slavery and Reconstruction. He served as president of both the American Historical Association, in 1913, and the American Political Science Association, in 1922. More a theorist than an empirical research scholar, he nonetheless supervised dozens of dissertations, and the Dunning School became the dominant influence on the next generation of historians.

In Dunning’s view, slavery was mostly benevolent, and Reconstruction was a vicious scheme to deny the South’s leading citizens their rights, operated by a vengeful Union army and manipulated by opportunistic “carpetbaggers” from the North and local “scalawags” who collaborated with the South’s Northern oppressors and corrupt Blacks. The trampled rights of freedmen were largely ignored in these accounts. D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, replete with outrageously racist stereotypes, dramatized these fictions and was seen by tens of millions of Americans, both Northern and Southern.

This version of history, which was dominant from the 1860s through the first half of the 20th century, chimed perfectly with the use of Jim Crow laws and court decisions that wiped out the last vestiges of Black civil rights and Black representation in Congress and in local Southern governments. It chimed as well with state terrorism and lynchings as the necessary way to maintain a racist order that was slavery in everything but name.

John Kennedy’s famous book, Profiles in Courage, written in 1956 (and ghostwritten by his aide Ted Sorenson), which helped establish Kennedy as a contender for the presidency, adopted the Dunning view of the Lost Cause. The fact that the book won a Pulitzer shows the persistence of Dunning’s influence.

In one of his eight profiles, Kennedy lionizes Sen. Edmund Ross of Kansas for refusing to vote to convict President Andrew Johnson for defying Congress on Reconstruction after the House impeached him. Had Ross voted to convict, Johnson would have been removed from office. Ross’s vote was really a profile in cowardice. Kennedy awarded another profile in courage to Sen. Daniel Webster, a Northerner, for bravely supporting the Fugitive Slave Act, part of the Compromise of 1850, allowing escaped slaves to be hunted down in free states.

As late as the 1960s, when I went to high school, a popular exam question was whether the Civil War was about abolishing slavery or about states’ rights and preservation of the Union. The “correct” answer was the latter.

It was only with a new wave of historians, beginning with W.E.B. Du Bois as early as the 1930s, that the standard narrative of the Lost Cause began to be overthrown by scholarly evidence. The work of John Hope Franklin, Eugene Genovese, Kenneth Stampp, Stanley Elkins, and C. Vann Woodward (and later, Eric Foner), among others, went deeper into how slavery actually functioned, the arduous journey from slavery to freedom, and the forgotten contributions of Black intellectuals and elected officials after the Civil War. Contemporary works such as the autobiography of Frederick Douglass were rediscovered, and the true picture of the dehumanizing brutality of slavery emerged.

The Trump who took offense at the Smithsonian’s emphasis on “how bad slavery was” is the same Trump who said of the pro-Nazi riot at Charlottesville, in 2017, that there were “good people on both sides.” Trump’s blurting out what he really thinks, and his whitewashed view of slavery, provide a window into his crusade against DEI. Evidently, for Trump, Black people have had things too easy, going all the way back to slavery times, while whites have been oppressed.

Let’s see. It was in Trump’s own lifetime that President Truman integrated the armed forces; that Jackie Robinson became the first Black player allowed in the major leagues; that strict segregation of Southern schools was overturned by the Supreme Court (though massive de facto segregation persists); that Emmett Till, among many others, was lynched, often with the complicity of local law enforcement; that Congress finally, belatedly, passed three great civil rights acts, after the heroism and civil disobedience of the civil rights movement; and that Southern Blacks could finally vote.

And then the progress went into reverse, as progress so often does, abetted by Republican appointees to the Supreme Court and now supercharged by Trump’s war on DEI.

We now await the tribute to William Archibald Dunning, and the exhibit at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, curated by Trump, on all the great things about slavery.

The Trump who took offense at the Smithsonian’s emphasis on “how bad slavery was” is the same Trump who said of the pro-Nazi riot at Charlottesville, in 2017, that there were “good people on both sides.” Trump’s blurting out what he really thinks, and his whitewashed view of slavery, provide a window into his crusade against DEI. Evidently, for Trump, Black people have had things too easy, going all the way back to slavery times, while whites have been oppressed.

Let’s see. It was in Trump’s own lifetime that President Truman integrated the armed forces; that Jackie Robinson became the first Black player allowed in the major leagues; that strict segregation of Southern schools was overturned by the Supreme Court (though massive de facto segregation persists); that Emmett Till, among many others, was lynched, often with the complicity of local law enforcement; that Congress finally, belatedly, passed three great civil rights acts, after the heroism and civil disobedience of the civil rights movement; and that Southern Blacks could finally vote.

And then the progress went into reverse, as progress so often does, abetted by Republican appointees to the Supreme Court and now supercharged by Trump’s war on DEI.

We now await the tribute to William Archibald Dunning, and the exhibit at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, curated by Trump, on all the great things about slavery.

Robert Kuttner is co-founder and co-editor of The American Prospect, and professor at Brandeis University’s Heller School.

Used with the permission. The American Prospect, Prospect.org, 2024. All rights reserved. Click here to read the original article at Prospect.org.

Click here to support The American Prospect's brand of independent impact journalism.

Pledge to support fearlessly independent journalism by joining the Prospect as a member today.

Every level includes an opt-in to receive our print magazine by mail, or a renewal of your current print subscription.