Film Review - Dave Van Ronk's Ex-Wife Takes Us Inside Inside Llewyn Davis

I was married to and managed Dave Van Ronk, the folksinger whose memoir spurred the Coen brothers' new movie, Inside Llewyn Davis. David and I were together from fall 1957 to fall 1968 and had been married for seven of those years when we separated amicably and regretfully. We remained good friends until he died. No one ever contacted me about the movie; Oscar Isaacs tried to, but I didn't get his message. We met once while it was being filmed. So I don't know much more about its creation than anyone else.

I knew the movie portrayed someone who eluded success -- or whom success eluded. I knew it wasn't supposed to be about David but used some of his memoir as background and his music as a theme. But I didn't expect it to be almost unrecognizable as the folk-music world of the early 1960s.

The mockup of MacDougal Street isn't exactly what it was in 1961, but it's more or less correct. The flights of stairs to top-floor apartments remind me of our first place, a fifth-floor walkup, and of those of friends, although the apartments are remarkably clean: No one I knew could keep soot out of apartments with roaches, pipes, and ceilings decorated by patterns created by fallen plaster. The Gaslight looks wider than it was, but the movie shows a shiny bar, which wasn't in the club -- there was no bar and nothing in the coffeehouse was shiny -- and the wonderful Tiffany (or Tiffany-style) lamps have been replaced with clear glass light fixtures. The back alley didn't exist, but the Coens need it for their story.

None of that bothers me. What bothers me is that the movie doesn't show those days, those people, that world.

In the movie, Llewyn Davis is a not-very smart, somewhat selfish, confused young man for whom music is a way to make a living. It's not a calling, as it was for David and for some others. No one in the film seems to love music. The character who represents Tom Paxton has a pasted-on smile and is a smug person who doesn't at all resemble the smart, funny, witty Tom Paxton who was our best man when we married.

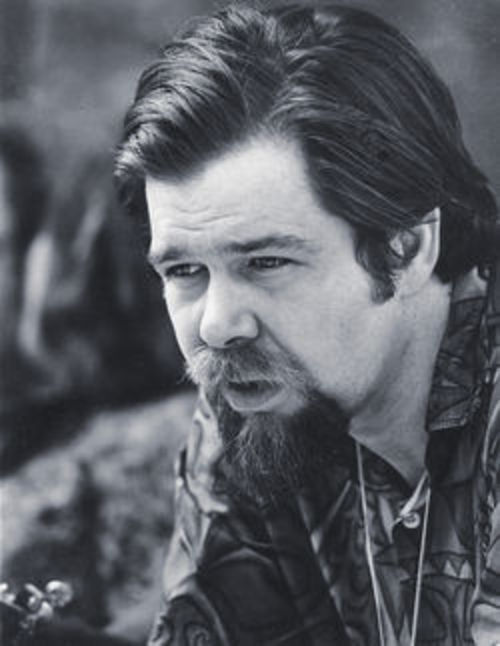

Dave Van Ronk

(The Village Voice // Courtesy Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Diana Davies)

In the film, the Jim and Jean characters, Llewyn Davis's close friends, are at least as well-known as Davis. Davis sometimes sleeps on their couch and has impregnated Jean, who is a bitchy woman. In real life, David and I considered Jim and Jean's music "white bread," one of the terms we used about folk singers who bounced up and down and smiled and sang "sweet" songs. We didn't socialize. However, Jean certainly was not a bitchy person.

The owner of the Gaslight tells Davis he has "fucked" Jean. He says that's a standard part of how a woman gets hired. That's crap. No matter how much of a creep a club owner might have been, that was not part of the process anywhere.

The sequence that bothers me the most is when Llewyn Davis arranges an abortion for the Jean character. He goes to the office of a doctor he'd paid $200 two years before for an abortion for another woman. He learns she never had the abortion and that apparently he has a two-year-old kid. OK, the Coens can create all the babies they want. But Davis and this respectable doctor sit and talk pleasantly about two women's abortions. In 1961 abortion still was illegal. It was difficult to find a doctor to do one. No one walked into a doctor's office and said, "Abortion, please." Mostly, abortions were arranged by telephone with practitioners whose names were hard to get. One good friend of ours had to go way uptown late at night for a procedure done in a place that barely resembled a medical office, and she paid $400 in 1960. This was the era of using coat hangers to try to abort. In fact, a few years before David and I met, the only woman he ever knew that he impregnated (she was about 16 at the time and David was 19) rode a bike down several flights of stairs to get rid of his fetus. Nor did men arrange abortions for women. The treatment of abortion in the movie as a casual, easily accessible procedure is cavalier, and I think it's insulting to all the women who had one before Roe v. Wade. In the movie, no one is nice. There are hints of friendliness in the Tom Paxton character and in Jim, who gets Davis some studio backup work (which didn't exist for folk musicians at that time). Everyone is somewhat dumb and somewhat mean. There's no suggestion that these people love the music they play, none that they play music for fun or have jam sessions, not a smidgen of the collegiality that marked that period.

Musicians supported each other. David and I had hordes of people in our apartment several times a week, many of them folksingers, many of them uninvited drop-ins who always were welcomed. I cooked; we talked politics; the musicians played. They introduced new songs and arrangements and often jammed. We had fun. If a new club opened, folksingers told each other about it and recommended one another to the club owner. When a new coffeehouse in Pennsylvania stiffed David, Tom Paxton refused to play there until David was paid. (He wasn't and Tom didn't.) When I received a series of obscene phone calls and the police said they couldn't do anything, Gaslight performers "babysat" while I stayed home to study for graduate exams. Noel Stookey, Tom Paxton, Hugh Romney (later known as Wavy Gravy), Len Chandler, and others came over between their sets and hung out while I worked.

In the 1950s and '60s, there were other folk-music scenes. The old-timey musicians; the bluegrass people; the people around Alan Block's sandal shop; the people the real Jim and Jean hung out with. There was some interaction, but even if the people in those groups didn't see each other daily or weekly, there was goodwill. No one would know that from Inside Llewyn Davis.

I'm not detailing the ways in which Llewyn Davis differs from David. There are so few similarities, it would be easier to focus on them. The Coens say the movie isn't about Dave, and they are correct. Two wonderful scenes do relate specifically to David, though. In one, Llewyn Davis asks Mel, the owner of the record company that released his first album, for royalties, telling the man he doesn't even own an overcoat. Mel says, "Here, take my overcoat." When Davis finally takes it, Mel grabs it back and gives Davis $40. Mel is Moe Asch, owner of Folkways Records, and yes, that happened. In another scene, Davis says (perhaps sarcastically) to someone in the seaman's union, "You won't give me my papers because I'm a communist?" The man mutters, "Shachtmanite." That's a political reference that almost no one in the world will get -- but to me, who hung around but didn't join a small socialist sect known as the Shachtmanites, it's very, very funny.

And I was taken with the Oceanic art Andrea Vuocolo, Dave's widow, loaned the movie for use in the apartment of an unknown, invented older uptown couple. One piece is the best Oceanic one David and I had, which he took when we separated (I got our books and wonderful record collection, along with other art; he had record-borrowing privileges), and another on the wall that he got later is stunning.

There are other pluses. Most of the acting is very good. Oscar Isaac is excellent -- he's real, and he brings pathos and anger to Llewyn Davis. His performances of David's songs are good, although I don't know why he gets an arranger's credit for "Dink's Song"; Andrea should collect royalties for David's arrangement of that. Carey Mulligan carries off being both bitchy and a good singer. John Goodman is wonderful as a sarcastic prick who sounds as though he comes out of the jazz world of several years earlier; he derives from Doc Pomus, who sang blues in the 1940s and later became a songwriter. F. Murray Abraham doesn't look like Albert Grossman, who had a full head of hair, but he has perfected Albert's blank stare.

The photography is excellent. The setting is winter, and a lot of the movie is filtered through snow and fog. The lighting is stunning.

The music? It's done well, but the movie never shows how it comes about. The inept Llewyn Davis arranged some of those songs? Sang them as well as Oscar Isaacs does? I don't believe it. That schmuck couldn't make that music. The Coens say they hope to create a revival of the music through the movie. A revival of traditional music is already under way. But I can't see the depressing world shown in this movie attracting people to it. I hope it at least attracts them to David's music and helps sell a lot of his CDs.

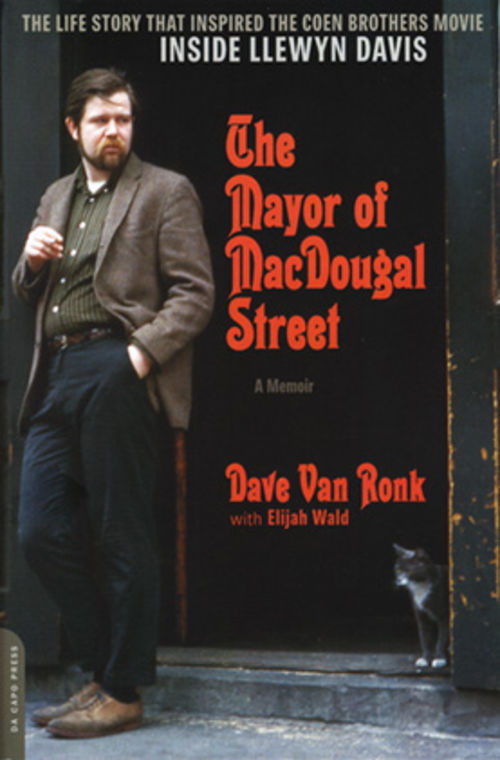

Oscar Isaac in Inside Llewyn Davis.

(The Village Voice // CBS Films)

Related posts, also from The Village Voice: