Fifty Years of Get-Tough

On July 16, 1964, shortly after 9:20 a.m., James Powell died on a sidewalk on East 76th Street, far from his native Bronx. He was 15 years old. Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan of the New York Police Department (NYPD) had shot the African American teenager three times, claiming that Powell had lunged at him with a knife. Powell’s peers insisted he had been unarmed. Either way, to the white owner of the apartment building where Powell died, who had sprayed African American teens with a garden hose and threatened them with racial taunts, and Gilligan, the white 17-year police veteran, Powell and his friends did not belong in the lily-white, wealthy Upper East Side. Indeed, they had acted on that presumption.

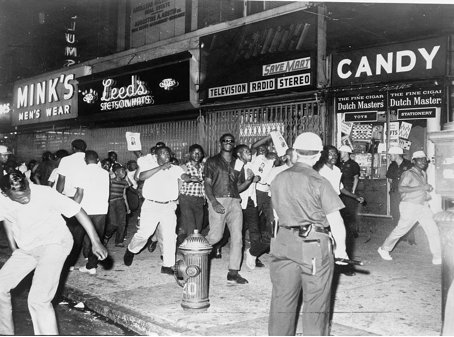

Word of Powell’s death soon drew 300 African American youth and 75 police officers into the area. The youth pelted the police with soda bottles. Some shouted, “This is worse than Mississippi,” and “Come on, shoot another nigger.” And so began, 50 years ago today, the Harlem Riot of 1964—the first of seven sizable African American uprisings that summer.

After six days, 465 arrests, more than one hundred injured, over $500,000 in property damage, and one death, the Harlem Riot finally came to an end. What did it mean? For African Americans? The police? Also: where did it come from? The 50-year anniversary presents an opportunity to reexamine the significance of the uprising in Harlem and other cities that summer and the more than 300 riots that rocked cities of every size across the country over the next three summers, comprising by far one of the most turbulent periods of urban rioting in United States history. Although Americans still think of the 1960s riots as many did at the time—the Civil Rights movement exploding in the North, the desperate cry of the marginalized inner-city poor—the roots of those events lay in a long War on Crime, in the history of big-city policing and urban community street justice.

Demonstrators carry posters with a picture of Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan. Throughout the riot, some chanted, “Killer Cops!” James Farmer, co-founder of the Congress of Racial Equality, called July 18 “New York’s night of Birmingham horror,” referencing the Alabama city’s use, in May 1963, of night sticks, water cannons, and police dogs against nonviolent Civil Rights marchers.

Harlem in particular and the 1960s riots in general speak directly to our current moment of increased legislative and public concern over the War on Drugs, mass incarceration, and stop-and-frisk—in NewYorkCity especially [1, 2, 3] —and their connection to growing wealth inequality. Two weeks before the riot, one of the country’s first stop-and-frisk laws went into effect in the city. In early March, Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller, known as a liberal member of his party and later famous for his “get-tough” drug laws in the early 1970s, signed two anti-crime bills to formalize and extend police power. The frisk bill gave police greater latitude to stop and detain people on the street. Another bill, termed “no-knock,” authorized police to search private residences without notifying the occupants if they have obtained a warrant.

Many believed the frisk law necessary in light of the United States Supreme Court’s decision in 1961 mandating the exclusion of illegally seized evidence from state criminal trials. The new law relaxed the probable cause requirement for arrest by permitting police to gather evidence on the street on the basis of “reasonable” suspicion. New York City patrolmen needed the procedural guidance. Asked to demonstrate a frisk in court in 1962, an officer “practically lifted” a lawyer off his feet, to try to shake evidence to the ground. Critics of the law, such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), argued that it would lead police to continue their ongoing harassment of minority citizens. Police training manuals already counseled officers to stop and question—and possibly detain—“suspicious” characters, defined as people who “do not belong.” In the postwar period, this could mean anyone on the social margins: an interracial couple, a person in bohemian dress, a black man walking outside at night, a group of minority youth standing on the corner.

In the 1960s, state and federal courts sought both to restrain flagrantly unconstitutional police practices and, at the same time, prescribe rules that, in effect, enlarged their discretionary power on the street. The courts trusted the crime-fighting expertise of police leadership. After World War II, a new generation of police reformers had promised to “professionalize” the police service by making it more efficient and scientific. A classic reform in this vein was “aggressive preventive patrol.” The innovation of Orlando Wilson, who took over Chicago’s department in 1960, this tactic combined a more efficient dispatch system and one-man patrol cars. Like “psychological warfare” against the potential criminal, Wilson said, it “gives the impression of the police being everywhere.”

Aggressive preventive patrol became the watchword of the new “professional” police in the 1950s and 1960s. Big-city departments sometimes waged war on the street corner at the behest of middle-class African Americans. In New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles—every major city—black elites long had complained about police neglect. The corner-loafer symbolized the problem. Men standing on the corner were said to harass women and block pedestrian traffic; they were an eyesore that threatened the respectability of the neighborhood. Elites frequently requested that police disperse these troublemakers. They sometimes backed curfew laws to discipline wayward youth. Thus, the 1960s riots rebelled not only against “outside” police authority but also against the class pretensions of the established African American leadership.

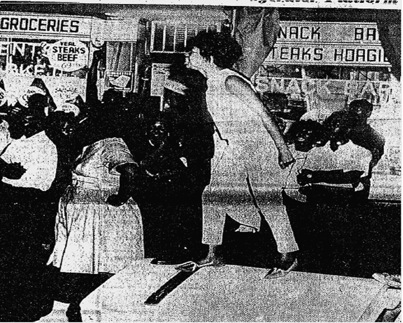

Florence Mobley, in North Philadelphia in late August 1964, was heard to curse the NAACP leadership and declare to the men nearby: “I’m a black woman. Let them take me.” Quote: Philadelphia Bulletin, August 29, 1964. Picture, printed during Mobley’s trial: Philadelphia Tribune, September 19, 1964.

In the 1960s, roughly one-half of all arrests each year nationally qualified as harassment arrests, for vagrancy, drunkenness, or blocking the street or sidewalk. The Philadelphia Police Department termed this struggle over urban space the “battle of the corner.” Departments established special squads to win the war for public order. To be a member of New York’s Tactical Patrol Forces in 1959, when the squad was formed, an applicant had to be at least 6 feet tall, under the age of 30, and trained in judo. A former member of the “Ass-Kicking Squad” has described it as “bare-knuckle law enforcement.” When rioting and crime rates surged in the middle of the decade, departments enlarged these units and armed them with tear gas, mace, and, in the case of Miami and other cities, even tanks. Chicago had “flying squadrons,” Baltimore designated “indicted corners,” and Atlanta tasked “corner generals.” The list goes on.

For all their rhetoric about scientific crime detection, patrolmen often relied upon rough justice to get the job done. Many officers lacked basic equipment; some had to purchase their own uniforms and firearms. In-service training was minimal until the end of the 1960s. Arrest procedures also were very different than they are today. In Philadelphia, for example, individual officers did not regularly carry handcuffs until the late 1960s; nor did patrol cars have a secure backseat. Arrests took time as officers waited for the patrol wagon to arrive. In 1963, the Police Advisory Board observed that even “after the arrest had been made, the individual was not handcuffed.” As a result, “additional force” was required “to subdue the individual again.”

Arrests quite literally could be a battle of the corner, especially in urban minority neighborhoods. In interviews for a study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, one officer explained: “If you stay there over that limit and most of the time you’re there your prisoner is real difficult, you might have a riot.” He went on: “It could create a riot because this guy won’t come along with you now. He’s not going to draw this large crowd and then meekly go with the police. He’s drawing this crowd to show them that he’s a man and nobody’s going to get the best of him.” A 1967 research study of police-citizen interactions in Boston, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., discovered that, 30% of the time, police encountered at least five bystanders when they arrested an African American person.

Clearly, then, post-war big-city policing differed strikingly from that which prevails today. We can find its counterpart in the street justice of the urban crowd. Significantly, nearly all of the 1960s riots began at the point of arrest or, at least, in response to a police incident.

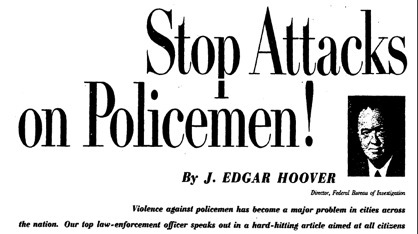

For as long as police departments have existed, urban crowds have tried to rescue police prisoners. But after World War II, the temper and scale seemed to shift. Probably on the rise numerically, though difficult to measure, bystander interventions captured the attention of the national press and the police establishment. In 1963, president of the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) and Cincinnati Police Chief Stanley R. Schrotel told U.S. News and World Report about his growing concern about the “people assembled as spectators where an arrest is being made tend to side with the prisoner” and “sometimes…openly attack the police in an attempt to free the prisoner.” Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s—before July 1964, significantly—city papers in Milwaukee, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Baltimore—virtually every major city—reported on crowds who tried to rescue prisoners.

Los Angeles Times, October 22, 1961, p. TW4

In August 1963, Los Angeles youths managed to free a prisoner and subsequently were charged with violating the lynch law. The Rochester riot in late July 1964 began when an officer attempted to arrest a popular leader of a youth group at a community dance. The crowd surged on the officer to take back the young man. In late August, in Philadelphia, a particularly strong African American man wrestled several police officers after they dragged an African American woman out of her car because she had refused to move it from a crowded intersection. By then, hundreds had gathered. The three-day riot was on. Some shouted that “white cops had no business” in North Philadelphia. African American business-owners marked their store windows with “Soul Brother.” Race clearly mattered, but, less obviously, it also didn’t. Worth noting, the first arresting officer had been African American, a member of the feared Motor Bandit Patrol.

Harlem also wasn’t the first such riot of that summer. Two weeks before, St. Louis police responded to a call about a sick African American woman. They arrived to find her two sons fighting in the front yard. When they tried to break up the fight, 500 to 1,000 bystanders attacked the officers, pelting them with soda cans and bricks. The police ultimately used dogs and tear gas to quell the disorder. The 1964 riots also did not stop at summer’s end, with Philadelphia, as commonly assumed, but continued in similar fashion into the fall. In October, Baltimore police tried to disperse a handful of “disorderly teenagers” from the street corner and in the process confronted an estimated crowd of 200 bystanders who swore at the officers and tried to help their captives escape.

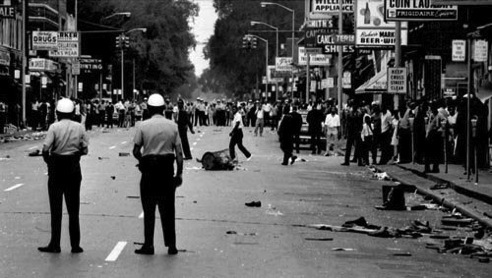

Similar examples stretch back into the twentieth century, and seem to mirror the rise of so-called professional police practices. They also multiply by the hundreds over the next few years as the riots incrementally escalated. In the aftermath of a riot in their city, police executives often expressed astonishment that routine policing had produced such catastrophic results. After the Detroit Riot of July 1967—perhaps the most destructive urban unrest of the twentieth century—Commissioner Ray Girardin reassured Mayor Jerome Cavanagh that the raid on the illegal after-hours bar, or “blind pig,” which sparked the uprising, had been “routine.” Girardin then detailed nine other raids his officers had conducted on the same bar in the previous sixteen months, which, he added, patrons seemed to accept, albeit grudgingly. “The only thing out of the ordinary” on the night of July 22-23, he stressed, “were the numbers found in the bar”—and out on the street. Within an hour after police entry, over 200 people stood nearby, watching.

In the Detroit Riot of July 23 to 27, 1967, 43 people died, 1,189 were injured, 7,200 were arrested, 1,700 stores were looted, and 1,400 buildings were burned. Total property damage was estimated to be at least $32 million (roughly $228 million in 2014 dollars). For the entire 1964 to 1968 period, as many as 190 people died—the vast majority, African American.

Thus, the July Harlem uprising sat at an historic intersection in at least two senses. It straddled an older world of small-scale street justice battles over urban space, in which crowds somehow believed they could overpower the arresting police officer, and the explosive, much more destructive confrontations of the next three years. Harlem also took place at a moment of transition in big-city policing. The older style of policing, often baldly racist and frequently ineffective, soon would give way to Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) teams, first established in Los Angeles in 1967, and their specialty in no-knock raids; stop, question, and frisk on a scale only attainable with the advent of computers; and a war mentality to handle a variety of urban social ills, including drug use, chronic poverty, and mental illness.

Despite their massive scale and their break from the dominant historic pattern of whites assaulting nonwhites, commemoration of the 1960s riots has been minimal. The same can be said for historical scholarship. In some cities, most notably in Los Angeles where the Watts Festival was held for many years after the uprising of August 1965, local groups have organized events to rally for social justice and deter future violence. Sometimes a riot spurred social movement building—as was the case in Rochester in the mid to late 1960s. More recently, filmmakers and public historians have begun to revisit the period. In 2008, professors at the University of Baltimore hosted a conference and conducted oral history interviews about the uprising that took place after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Their effort culminated in the publication of an edited volume. Also the release of July ’64 and Revolution ’67, two documentaries about Rochester and the 1967 riots, respectively, appear to have inspired community discussion. We probably can expect more films and publications as the 50-year mark approaches for the major riots of the period in Watts, Newark, Detroit, and Washington, D.C.

Commemoration and the historical writing that informs it tend to emphasize the “conditions” of poverty and discrimination that supposedly caused the riots. This “urban crisis” school holds sway among historians as well. The impulse is understandable as a corrective to the “get-tough” response of many Americans at the time who understood the riots to be criminal lawlessness, the acts of a group not yet ready for full citizenship. Though, of course, it should be noted that poverty and discrimination have characterized the entire African American experience and perhaps cannot explain the turn to rioting—as opposed to social protest—in the 1960s.

The history chronicled here, of urban street justice, offers a different commemorative path for us to consider. It should prompt us to reevaluate the machinery of urban criminal justice, an effort already underway. The 1964-1968 period was a moment of heightened community demand and protest across the country for more democratic control of police departments. The Harlem uprising reinvigorated public debate about independent civilian review of police practices. Just last year, in fact, New York City established the Office of Inspector General to provide a modicum of civilian oversight of the NYPD. Yet, however much civilian review boards force us to recognize that police departments were established under civil not military authority, they remain an incomplete solution to the problems of policy and social institutions. Indeed, over the next four years, as we remember the 1960s rioters, who responded to official rough justice with their own style of community street justice, we might remember that carceral solutions to social ills tend to produce the outcomes they hope to resolve.

Alex Elkins is a doctoral candidate in history and is writing a dissertation on the 1960s riots and the rise of “get-tough” policing. He was a fellow at the German Historical Institute in 2013-2014.