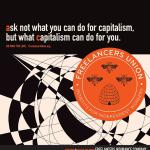

The Freelancer Economy is Here. Should We Celebrate?

Early this month, the Freelancers Union released the results of an Edelman study which found that an astounding 34 percent of the U.S. workforce is now comprised of “freelancers.”

In considering the results of the co-commissioned study, the Freelancers Union was in an oddly celebratory mood:

But this is more than an economic change. It’s a cultural and social shift on par with the Industrial Revolution. Just as the move from an agrarian to an industrial society had dramatic effects on social structures around civil rights, workforce participation, and even democracy itself, so too will this shift to a more independent workforce have major impacts on how Americans conceive of and organize their lives, their communities, and their economic power.

This and countless other studies make it hard to contest the notion that the “end of jobs” is indeed nigh, and few would argue with the Freelancers Union’s assertion that this major labor shift will have a massive social impact. But whether we should happily embrace this shift is still up for debate.

On one side of that debate is the Freelancers Union, which is eager to proselytize about the luxury of the freelancer lifestyle—even though the organization reports that many of its members suffer economic vulnerability and 12 percent receive food stamps. The announcement of the study comes on the heels of a report they released in July entitled “How to Live the Freelance Life—Lessons from 1,000 Independents,” an independently conducted survey of both FU members and non-members that found that 88 percent of freelancers wouldn’t take a traditional job if it were offered to them.

“Regardless of how people come to freelancing, what we see is that there are a lot of commonalities in how they feel about it once they get there,” says the Freelancers Union’s Dan Lavoie. "Once they start, they don’t want a nine to five.”

Without a doubt, many independent workers feel empowered, grateful that the Digital Age has provided them with the tools to make their own way with an incredible degree of flexibility. (Not to mention the highly venerated mid-day naps, workcations, and pants-free meetings.)

But the “we don’t need ‘em anyway” attitude of the Freelancers Union is at odds with a very different narrative about the gig economy which tells us that “independence” from formal employment isn’t so liberating—and that hiring “consultants” or contingent workers is a strategy often used by bosses to better exploit their workforce.

Anyone who has kept up on organizing adjuncts and truckers, for example, will be well versed in this phenomenon. In many different industries, desperate workers are wrestling with employers who, in an attempt to avoid paying benefits, categorize them as “contractors” or are careful not to give them full-time hours. Many of these workers are dependent on the whims of their employers for steady work, as they are likely to find identical conditions if they pursue employment with other companies in their fields.

So what’s with the discrepancy? The reported experiences of blissed-out “freelancers” and those of more disempowered, vulnerable, precarious “free agents” are both accurate, but neither paints the full picture of the “post-job” world.

For one thing, there is a definitional problem: What exactly is a “freelancer”? The term generally implies a self-employed worker in a professional, white-collar position, while the same word would rarely be used to describe an unskilled independent laborer. But if a custodian files a W9, is he a freelancer? The lines between “freelancers” and other kinds of independent workers are blurry and somewhat superficial.

Recent studies like the Freelancers Union’s don’t clearly address this difference; they may outline, as the September study did, the different kinds of freelancers and the process for determining whether or not the workers being surveyed were in fact independent from employers (and to what degree they were independent). But most of the studies have failed to specify whether those included in the surveys were white- or blue-collar workers, which industries they focused on or how the sampling was collected.

So when the Freelancers Union conducted an “online survey of 1,186 freelancers” in July and concluded that 88 percent are happier being independent than being formally employed, I get hung up on how “freelancer” is defined. My guess is that those 1,186 people are self-identified freelancers who spend their days in front of a computer—rather than subcontracted construction workers being paid below the prevailing wage by a boss who figured he could pay his workers less by making them independent contractors.

Whereas the September study, which found that 34 percent of Americans are now reportedly freelancers, likely represents a wider swath of the population because it is more generous in its assessment of who qualifies as a freelancer. Of the 34 percent of the population gone freelance, are we to assume that 88 percent think they’re better off without formal employment? Somehow, I doubt it.

This may sound tedious, but we can’t have a meaningful conversation about the “end of jobs” without a complete understanding of the different parties affected. If we don’t know what we mean when we say “freelancer” or “independent worker,” we can misrepresent many workers' realities—and that can be dangerous.

In a previous article for In These Times, Sarah Jaffe wrote, “The rise of the ‘free agent’ worker has at least as much to do with the desire of businesses to have an easy-hire, easy-fire, just-in-time workforce … that absorbs … most of the labor costs, as it does with workers who simply enjoy the freedom of not having a boss. Power is as big or bigger a force as technology in shaping the labor landscape today.” This cuts to the heart of the difference between “freelancers” and other kinds of independent workers: Those with more power relative to their employers are more likely to be referred to as “freelancers,” whereas those with less power are “free agents” or “contingent workers.” But they’re all being lumped into this “34 percent” we’re now recognizing as “freelancers.”

Jaffe points out that the concept of full-time, salaried work with benefits was one invented by blue-collar unions during the New Deal era—and that the conventions of the nine-to-five gig continue to serve some of the needs of lower income workers, even if the jetsetting consultants of the world have deemed it passé. Failing to recognize the widely differing ways independent work is experienced today threatens to sanctify a broken system that contributes to growing income inequality and marginalizes efforts by independent workers to organize and assert their rights. It may be easy for some to celebrate the “end of jobs,” as the Freelancers Union seems to do when it proclaims, “The era of big work is over” and “Freelancing is the new normal.” But those workers for whom the basic guarantees that came with the “job” were most essential in the first place are probably less likely to feel like partying when those meager guarantees evaporate.

To be fair, the Freelancers Union’s targeted constituency is largely professionals rather than the working poor, and its benefits only extend to skilled workers in “professional” fields (childcare providers being the only exception). The FU has also led an important dialogue about “middle-class poverty” that acknowledges that the freelancer life does often come with its own financial challenges and explores possible solutions. But in the context of a heated national discussion about the depressing predicament of precarious workers, it might tread a bit more carefully in its promotion of the unaffiliated lifestyle.

What’s needed in the conversation about independent work is greater nuance and increased sensitivity to high stakes battles that certain unskilled (and skilled, for that matter) workers are waging against exploitative employer practices. We need a thoughtful examination of how different kinds of independent workers will be affected by a gleeful rush toward a post-job world. Because I’ll bet if you ask the freelance truck drivers, most of them would tell you they’d take a full-time job any day.

The Freelancers Union’s attempt to claim 34 percent of the population as mostly delighted freelancers clouds our understanding of the need for reform. While the Freelancers Union is doing important work to support a select group of freelancers, its DIY approach isn’t likely to work for other independent workers; those workers who are more replaceable may still need to go to war against industry leaders if they’re going to access acceptable working conditions.

The Freelancers Union can’t claim to represent 34 percent of the population unless it finds a way to fight for 34 percent of the population—including the adjuncts, the truck drivers, the construction workers and all the others who are currently on their own.