Thanksgiving 2014 - Reality of History and Today's Meal

- Thanksgiving: A Native American View - Jacqueline Keeler (AlterNet)

- Thanksgiving - Seymour Joseph

- How America's Thanksgiving Turkeys Got so Huge - Svati Kirsten Narula (Quartz)

Thanksgiving: A Native American View

By Jacqueline Keeler

December 31, 1999

AlterNet

I celebrate the holiday of Thanksgiving.This may surprise those people who wonder what Native Americans think of this official U.S. celebration of the survival of early arrivals in a European invasion that culminated in the death of 10 to 30 million native people.Thanksgiving to me has never been about Pilgrims. When I was six, my mother, a woman of the Dineh nation, told my sister and me not to sing "Land of the Pilgrim's pride" in "America the Beautiful." Our people, she said, had been here much longer and taken much better care of the land. We were to sing "Land of the Indian's pride" instead.I was proud to sing the new lyrics in school, but I sang softly. It was enough for me to know the difference. At six, I felt I had learned something very important.

As a child of a Native American family, you are part of a very select group of survivors, and I learned that my family possessed some "inside" knowledge of what really happened when those poor, tired masses came to our homes.When the Pilgrims came to Plymouth Rock, they were poor and hungry -- half of them died within a few months from disease and hunger. When Squanto, a Wampanoag man, found them, they were in a pitiful state. He spoke English, having traveled to Europe, and took pity on them. Their English crops had failed. The native people fed them through the winter and taught them how to grow their food.These were not merely "friendly Indians." They had already experienced European slave traders raiding their villages for a hundred years or so, and they were wary -- but it was their way to give freely to those who had nothing.

Among many of our peoples, showing that you can give without holding back is the way to earn respect. Among the Dakota, my father's people, they say, when asked to give, "Are we not Dakota and alive?" It was believed that by giving there would be enough for all -- the exact opposite of the system we live in now, which is based on selling, not giving.To the Pilgrims, and most English and European peoples, the Wampanoags were heathens, and of the Devil. They saw Squanto not as an equal but as an instrument of their God to help his chosen people, themselves.

Since that initial sharing, Native American food has spread around the world. Nearly 70 percent of all crops grown today were originally cultivated by Native American peoples. I sometimes wonder what they ate in Europe before they met us. Spaghetti without tomatoes? Meat and potatoes without potatoes? And at the "first Thanksgiving" the Wampanoags provided most of the food -- and signed a treaty granting Pilgrims the right to the land at Plymouth, the real reason for the first Thanksgiving.

What did the Europeans give in return? Within 20 years European disease and treachery had decimated the Wampanoags. Most diseases then came from animals that Europeans had domesticated. Cowpox from cows led to smallpox, one of the great killers of our people, spread through gifts of blankets used by infected Europeans. Some estimate that diseases accounted for a death toll reaching 90 percent in some Native American communities. By 1623, Mather the elder, a Pilgrim leader, was giving thanks to his God for destroying the heathen savages to make way "for a better growth," meaning his people.

In stories told by the Dakota people, an evil person always keeps his or her heart in a secret place separate from the body. The hero must find that secret place and destroy the heart in order to stop the evil. I see, in the "First Thanksgiving" story, a hidden Pilgrim heart. The story of that heart is the real tale than needs to be told. What did it hold? Bigotry, hatred, greed, self-righteousness? We have seen the evil that it caused in the 350 years since. Genocide, environmental devastation, poverty, world wars, racism.Where is the hero who will destroy that heart of evil? I believe it must be each of us.

Indeed, when I give thanks this Thursday and I cook my native food, I will be thinking of this hidden heart and how my ancestors survived the evil it caused. Because if we can survive, with our ability to share and to give intact, then the evil and the good will that met that Thanksgiving day in the land of the Wampanoag will have come full circle.And the healing can begin.

[Jacqueline Keeler is a member of the Dineh Nation and the Yankton Dakota Sioux, living in Portland, Ore., finishing her first novel, "Leaving the Glittering World.". Her work has appeared in Salon, Huffington Post, AlterNet and Winds of Change, an American Indian journal ( published by the American Indian Science and Engineering Society.]

Of course the food,

the brimming platters,

the steaming bowls,

aromas wafting and mingling warm above the table,

tantalizing the taste buds of family and friends

gathered here.

Yes, the food, but what of us?

Was our guide the stomach or was it the heart?

This yearly ritual is reaffirmation

that while the effects of the feast are quickly abated

our appetites for each other are never sated.

Seymour Joseph

[Seymour Joseph is a graphic designer and author who for many years was a journalist with the Daily Worker and its subsequent incarnations. Today it's the online People's World.]

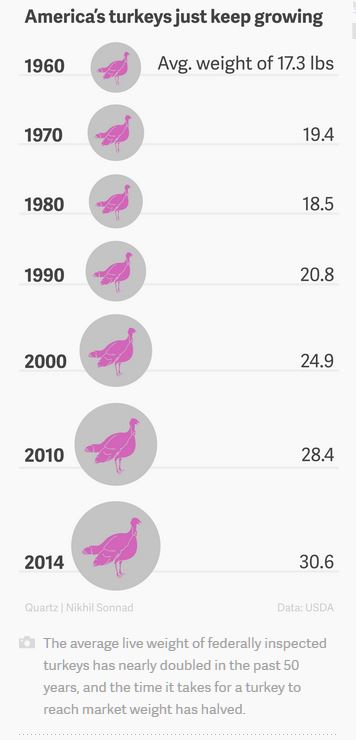

How America's Thanksgiving Turkeys Got so Huge

By Svati Kirsten Narula

November 26, 2014

Quartz

"You're slightly bigger than the fella I pardoned last year. "Former Pres. George W. Bush looks at "May" as he pardons the National Thanksgiving Turkey in the Rose Garden of the White House in Washington, November 20, 2007.

Reuters/Larry Downing // Quartz

Thanksgiving, the most food-focused of American holidays, provides a hearty occasion for this reminder: The dominant fruits, vegetables, and animals in modern farming are products of highly unnatural selection. Consider corn, which evolved from a fairly small, hard-to-eat plant called teosinte into maize, which European settlers and subsequent generations of farmers tweaked and perfected into the starchier, less-colorful "sweet corn" sold in supermarkets today. Consider the variety of apple known as the Red Delicious.

Or consider the turkey.

While the number of individual turkeys raised and slaughtered in the US each year is declining, total production of turkey meat has remained stable, pound-wise (PDF). That's because the average turkey comes with a lot more meat on its bones today than ever before.

The standard commercial turkey is a breed called the broad-breasted white, an apt name for a bird specifically bred to have large breasts full of lean, white meat, which many modern consumers prefer to the dark, stringy, fatty meat from other turkey parts. To call these turkeys "top-heavy" would not be inaccurate; neither is it factually wrong to call them "pathologically obese," a term favored by animal welfare groups.

They grow twice as fast today as they did in 1966 (PDF). They can't easily walk, and they can't mate, so most of the 235 million US turkeys raised in 2014 were brought into existence by artificial insemination-which the industry isn't ashamed about (PDF).

Whether consumers should be ashamed about modern turkey production is a matter of debate, one we can't sincerely advise discussing over Thanksgiving dinner-unless, that is, you're serving a heritage turkey instead of a Butterball and need to explain to guests why there isn't enough white meat to go around.

A more interesting question, though it's another unsavory one, is whether the modern turkey is a GMO (genetically modified organism). Most scientists would say no, it's not; selective breeding and genetic engineering mustn't be conflated. Today's turkeys, just like Belgian blue cows and Labradoodles, are products of the former. But conventionally raised turkeys, including some heritage ones, are fed GMO corn. Though it seems like splitting hairs, one of the pre-eminent, family-owned poultry farms in the US sells "organic," "non-GMO," and "heritage" turkeys separately.

[Svati Narula is a reporter for Quartz in New York. She was previously at The Atlantic, covering environmental economics, sports, and the sea.]