Election Math: How Fewer Voters Elect More Reps

https://portside.org/2014-11-28/election-math-how-fewer-voters-elect-more-reps

Portside Date:

Author: Jessica Jones

Date of source:

WUNC 91.5 - North Carolina Public Radio

It’s near the end of a long workday and math Professor Jonathan Mattingly is climbing a steep set of stairs to his office on Duke University’s campus.

"We share this hall with the physics department, physics starts somewhere right down there," Mattingly says. He opens the door to reveal an office that looks like it belongs to a math professor. There are books everywhere and a big chalkboard on one wall covered with half-erased equations. This is where Mattingly first got the idea to include one of his students, senior Christy Vaughn, in the mathematical conundrum of the 2012 U.S. Congressional Elections in North Carolina.

"One day I kinda had this idea that we should look at gerrymandering. And so I called her and I said I got an idea," says Mattingly. (Gerrymandering is the setting of electoral districts in an attempt to obtain political gain.)

"Right away I was very interested in this project because it’s just such a stark result that so few seats were [awarded to Democrats] when the popular vote was so different," chimes in Vaughn.

That was back in the summer of 2013, when articles were still circulating that blamed those results on gerrymandering at the General Assembly. But Mattingly, who specializes in probability, says no one had attempted to prove or disprove that theory mathematically.

Mattingly said they went in with an open mind. Maybe the discrepancies were due to geographical differences, or perhaps there was some gerrymandering that affected a couple of seats...whatever the result, they wanted the numbers.

"We wanted to ask ourselves, could we quantify, could we give some empirical force to the idea of what the right number of elected officials were," said Mattingly.

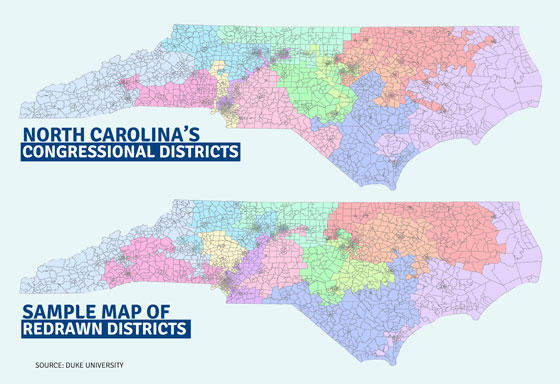

So Mattingly and Vaughn, who are both graduates of the North Carolina School of Science and Math, decided to create a series of district maps using the same vote totals from 2012, but with different borders.

Their work was governed by two principles of redistricting:

- A federal rule requires each district have roughly the same population.

- A state rule requires congressional districts to be compact.

Using those principles as a guide, they created a mathematical algorithm to randomly redraw the boundaries of the state’s 13 congressional districts.

Says Vaughn: "And then, we just used the actual vote counts from 2012 and just retabulated them under the different districtings."

"But there was a lot of work behind that. Christy did a tremendous amount of programming," says Mattingly.

It took the computer four weeks to draw a series of one hundred different maps. From a mathematical perspective, they represent one hundred different possibilities of drawing congressional lines.

The results

When Mattingly and Vaughn tabulated what would have happened had residents voted the same way but in differently drawn districts, they were surprised. Mattingly turns to his computer to pull up their work, which summarizes how the balance of the congressional seats would have come out under those 100 different maps.

"Right here, if you look at what’s happening," explains Mattingly, "here we have this bar chart with seven and eight Democrats elected. That happened over 50 percent of the time- and the vast majority of the time we had somewhere between six and nine Democrats elected over 95 percent of the time."

Mattingly says this chart- and the rest of the study-shows mathematically that the outcome of the 2012 congressional election- with four Democrats elected- was not representative of how people voted.

The response

Legal scholars who study redistricting say the work is interesting.

"It’s a wonderful academic project and a wonderful math exercise," says Justin Levitt, a law professor at Loyola University. He commends Mattingly and Vaughn for their work. But, he cautions, in the real world, there are many other factors that go into drawing district lines.

"One of them is our national commitment to minority voting rights," says Levitt. "It's really the strongest national commitment we have to minority representation anywhere, the voting rights act, and as I think the professor and student would say, their model districts don’t even comply with the voting rights act, that’s not what they were aiming to do."

Levitt says other factors matter too, including geography.

In response, Mattingly says it’s possible to design the program to account for minority representation, but he and Vaughn chose to keep it as simple and as transparent as possible for now.

They hope their study might serve as a kind of diagnostic tool that can help determine whether districts are fairly drawn or not.

Mattingly also hopes it might encourage more state lawmakers to think about how best to shape district lines.

"It wasn’t representative of the will of the people, and you ask yourself is this democratic? I mean if we really want to be in a democracy we should put in safeguards like we do for other things. We should put in safeguards to protect against gerrymandering in either direction."

Some lawmakers at the General Assembly have tried to add safeguards. But bipartisan bills to establish an independent commission to draw district lines haven’t made it out of committee.