Ten Things You Should Know About Selma Before You See the Film

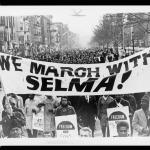

In this 50th anniversary year of the Selma-to-Montgomery March and the Voting Rights Act it helped inspire, national media will focus on the iconic images of “Bloody Sunday,” the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the interracial marchers, and President Lyndon Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act. This version of history, emphasizing a top-down narrative and isolated events, reinforces the master narrative that civil rights activists describe as “Rosa sat down, Martin stood up, and the white folks came south to save the day.”

But there is a “people’s history” of Selma that we all can learn from—one that is needed especially now. The exclusion of Blacks and other people of color from voting is still a live issue. Sheriff’s deputies may no longer be beating people to keep them from registering to vote, but in 2013 the Supreme Court ruled in Shelby v. Holder that the Justice Department may no longer evaluate laws passed in the former Confederacy for racial bias. And as a new movement emerges, insisting that Black Lives Matter, young people can draw inspiration and wisdom from the courage, imagination, and accomplishments of activists who went before.

Here are 10 points to keep in mind about Selma’s civil rights history.

1. The Selma voting rights campaign started long before the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Mrs. Amelia Boynton Robinson, her husband Samuel William Boynton, and other African American activists founded the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) in the 1930s. The DCVL became the base for a group of activists who pursued voting rights and economic independence.

2. Selma was one of the communities where the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) began organizing in the early 1960s.

In 1963, seasoned activists Colia (Liddell) and Bernard Lafayette came to Selma as field staff for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), known as “Snick.” Founded by the young people who initiated the 1960 sit-in movement, SNCC had moved into Deep South, majority-black communities doing the dangerous work of organizing with local residents around voter registration.

Working with the Boyntons and other DCVL members, the Lafayettes held Citizenship School classes focused on the literacy test required for voter registration and canvassed door-to-door, encouraging African Americans to try to register to vote. Prathia Hall, a SNCC field secretary who came to Selma in the fall of 1963, explained in Hands on the Freedom Plow:

The 1965 Selma Movement could never have happened if SNCC hadn’t been there opening up Selma in 1962 and 1963. The later nationally known movement was the product of more than two years of very careful, very slow work.

3. The white power structure used economic, “legal,” and extra-legal means, including terrorism, to prevent African Americans from accessing their constitutional right to vote and to impede organizing efforts.

SNCC’s organizing was necessary and extremely challenging because African Americans in Selma, despite being a majority in the community, were systematically disfranchised by the white elite who used literacy tests, economic intimidation, and violence to maintain the status quo.

According to a 1961 Civil Rights Commission report, only 130 of 15,115 eligible Dallas County Blacks were registered to vote. The situation was even worse in neighboring Wilcox and Lowndes counties. There were virtually no Blacks on the voting rolls in these rural counties that were roughly 80 percent Black. Ironically, in some Alabama counties, more than 100 percent of the eligible white population was registered.

Although many people are aware of the violent attacks during Bloody Sunday (when, on March 7, 1965, police brutally attacked marchers in Selma), white repression in Selma was systematic and long-standing. Selma was home to Sheriff Jim Clark, a violent racist, and one of Alabama’s strongest white Citizens’ Councils—made up of the community’s white elite and dedicated to preserving white supremacy. The threat of violence was so strong that most African Americans were afraid to attend a mass meeting. Most of the Lafayettes’ first recruits were high school students. Too young to vote, they canvassed and taught classes to adults. Prathia Hall remembers the danger in Alabama: “…n Gadsden, the police used cattle prods on the torn feet [of young protesters] and stuck the prods into the groins of boys. Selma was just brutal. Civil rights workers came into town under the cover of darkness.”

4. Though civil rights activists typically used nonviolent tactics in public demonstrations, at home and in their own communities they consistently used weapons to defend themselves.

On June 12, 1963, the night Medgar Evers was assassinated in Jackson, Mississippi, whites viciously attacked Bernard Lafayette outside his apartment in Selma in what many believe was a coordinated effort to suppress Black activism.

Lafayette believed in nonviolence, but his life was probably saved by a neighbor who shot into the air to scare away the white attackers.

This practice of armed self-defense was woven into the movement and, because neither local nor federal law enforcement offered sufficient protection, it was essential for keeping nonviolent activists alive.

5. Local, state, and federal institutions conspired and were complicit in preventing black voting.

Even with the work of SNCC and the Dallas County Voters League, it was almost impossible for African Americans to register to vote. The registrar’s office was only open twice a month and potential applicants were routinely and arbitrarily rejected. Some were physically attacked and others fired from their jobs. Howard Zinn, who visited Selma in the fall of 1963 as a SNCC advisor, offers a glimpse of the repression, noting that white officials had fired teachers for trying to register and regularly arrested SNCC workers, sometimes beating them in jail. In one instance, a police officer knocked a 19-year-old girl unconscious and brutalized her with a cattle prod.

|

|

| Photos: A brave young boy demonstrates for freedom in front of the Dallas County courthouse in Selma on July 8, 1964. Selma sheriff deputies approach and arrest him. Photos used by permission of Matt Herron/Take Stock Photos. |

In another example, in summer 1964, Judge James Hare issued an injunction making it illegal for three or more people to congregate. This made demonstrations and voter registration work almost impossible while SNCC pursued the slow appeals process. Although the Justice Department pursued its own legal action to address discrimination against Black voters, its attorneys offered no protection and did nothing to intervene when local officials openly flaunted the 1957 Civil Rights Act.

The FBI was even worse. In addition to refusing to protect civil rights workers attacked in front of agents, the FBI spied on and tried to discredit movement activists. In 1964, the FBI sent King an anonymous and threatening note urging him to commit suicide and later smeared white activist Viola Liuzzo, who was murdered after coming from Detroit to participate in the Selma-to-Montgomery March.

6. SNCC developed creative tactics to highlight Black demand for the vote and the raw violence at the heart of Jim Crow.

To highlight African Americans’ desire to vote and encourage a sense of collective struggle, SNCC organized a Freedom Day on Monday, Oct. 7, 1963, one of the monthly registration days. They invited Black celebrities, like James Baldwin and Dick Gregory, so Blacks in Selma would know they weren’t alone.

Over the course of the day, 350 African Americans stood in line to register, but the registrar processed only 40 applications and white lawmen refused to allow people to leave the line and return. Lawmen also arrested three SNCC workers who stood on federal property holding signs promoting voter registration.

By mid-afternoon, SNCC was so concerned about those who had been standing all day in the bright sun, that two field secretaries loaded up their arms with water and sandwiches and approached the would-be voters.

Highway patrolmen immediately attacked and arrested the two men, while three FBI agents and two Justice Department attorneys refused to intervene. (Read an account of the day by Howard Zinn here.)

This federal inaction was typical, even though Southern white officials openly defied both the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and constitutional protections of free assembly and speech. The FBI insisted it had no authority to act because these were local police matters, but consistently ignored such constraints to arrest bank robbers and others violating federal law.

7. Selma activists invited Dr. King to join an active movement with a long history.

By late 1964, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) were looking for a local community where they could launch a campaign to force the country to confront the Southern white power structure’s widespread discrimination against prospective Black voters.

At the same time, Mrs. Boynton, the longtime leader of the Dallas County Voters League, wanted to escalate the struggle in Selma and invited SCLC in. SCLC saw Selma as ideal because: (1) the ongoing work of SNCC and the DCVL provided a strong base of organizers and people who could be counted on to attend mass meetings, march in demonstrations, attempt to register, and canvass prospective registrants; (2) Sheriff Jim Clark’s volatile white supremacy led King to believe he was likely to attack peaceful protesters in public, drawing national attention to the white violence underlying Black disfranchisement; and finally, (3) the Justice Department’s own lawsuit charging racial discrimination in Dallas County voter registration reinforced the need for action.

8. Youth and teachers played a significant role in the Selma Movement.

An important breakthrough in the Selma Movement came when schoolteachers, angered by a physical attack on Mrs. Boynton, marched to the courthouse on Jan. 22, 1965. Despite the prominence of King and a handful of ministers in history books, throughout the South most teachers and ministers stayed on the sidelines during the movement. Hired and paid by white school boards and superintendents, teachers who joined the Civil Rights Movement faced almost certain job loss.

Young women singing freedom songs in a Selma church. July 8, 1964. (c) Matt Herron/Take Stock Photos.

In Selma, the “teachers’ march” was particularly important to the young activists at the heart of the Selma Movement. One of them, Sheyann Webb, was just 8 years old and a regular participant in the marches. She reflects in Voices of Freedom:

What impressed me most about the day that the teachers marched was just the idea of them being there. Prior to their marching, I used to have to go to school and it was like a report, you know. They were just as afraid as my parents were, because they could lose their jobs. It was amazing to see how many teachers participated. They follow us that day. It was just a thrill.

9. Women were central to the movement, but they were sometimes pushed to the side and today their contributions are often overlooked.

In Selma, for example, Mrs. Amelia Boynton was a stalwart with the DCVL and played a critical role for decades in nurturing African American efforts to register to vote. She welcomed SNCC to town and helped support the younger activists and their work. When Judge Hare’s injunction slowed the grassroots organizing, she initiated the invitation to King and SCLC.

Marie Foster, another local activist, taught citizenship classes even before SNCC arrived. In early 1965 when SCLC began escalating the confrontation in Selma, Boynton and Foster were both in the thick of things, inspiring others and putting their own bodies on the line. They were leaders on Bloody Sunday and the subsequent march to Montgomery.

Though Colia Liddell Lafayette worked side by side with husband Bernard, recruiting student workers and doing the painstaking work of building a grassroots movement in Selma, she has become almost invisible and typically mentioned only in passing, as his wife.

Diane Nash, whose plan for a nonviolent war on Montgomery inspired the initial Selma march, was already a seasoned veteran, leading the Nashville sit-ins, helping found SNCC, and taking decisive action to carry the freedom rides forward.

These are just a few of the many women who were critical to the movement’s success—in Selma and across the country.

10. Though President Lyndon Johnson is typically credited with passage of the Voting Rights Act, the Movement forced the issue and made it happen.

The Selma campaign is considered a major success for the Civil Rights Movement, largely because it was an immediate catalyst for the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on Aug. 6, 1965, the Voting Rights Act guaranteed active federal protection of Southern African Americans’ right to vote.

Although Johnson did support the Voting Rights Act, the critical push for the legislation came from the movement itself. SNCC’s community organizing of rural African Americans, especially in Mississippi, made it increasingly difficult for the country to ignore the pervasive, violent, and official white opposition to Black voting and African American demands for full citizenship. This, in conjunction with the demonstrations organized by SCLC, generated public support for voting rights legislation.

* * *

This brief introduction to Selma’s bottom up history can help students and others learn valuable lessons for today. As SNCC veteran and filmmaker Judy Richardson said,

This brief introduction to Selma’s bottom up history can help students and others learn valuable lessons for today. As SNCC veteran and filmmaker Judy Richardson said,

“If we don’t learn that it was people just like us—our mothers, our uncles, our classmates, our clergy—who made and sustained the modern Civil Rights Movement, then we won’t know we can do it again. And then the other side wins—even before we ever begin the fight.”

Emilye Crosby is professor of history and coordinator of Black Studies at SUNY Geneseo. She is author of A Little Taste of Freedom (University of North Carolina Press, 2005) and editor of Civil Rights History from the Ground Up (University of Georgia Press, 2011). She is currently a fellow at the National Humanities Center where she is working on a history of women and gender in SNCC.

Emilye Crosby is professor of history and coordinator of Black Studies at SUNY Geneseo. She is author of A Little Taste of Freedom (University of North Carolina Press, 2005) and editor of Civil Rights History from the Ground Up (University of Georgia Press, 2011). She is currently a fellow at the National Humanities Center where she is working on a history of women and gender in SNCC.

A longer version of this article can be found on the Teaching for Change website.