The Forgotten History of How Automakers Invented the Crime of "Jaywalking"

100 years ago, if you were a pedestrian, crossing the street was simple: you walked across it.

Today, if there's traffic in the area and you want to follow the law, you need to find a crosswalk. And if there's a traffic light, you need to wait for it to change to green.

in the 1920s, auto groups redefined who owned the city street

Fail to do so, and you're committing a crime: jaywalking. In some cities — Los Angeles, for instance — police ticket tens of thousands of pedestrians annually for jaywalking, with fines of up to $250.

To most people, this seems part of the basic nature of roads. But it's actually the result of an aggressive, forgotten 1920s campaign led by auto groups and manufacturers that redefined who owned the city street.

"In the early days of the automobile, it was drivers' job to avoid you, not your job to avoid them," says Peter Norton, a historian at the University of Virginia and author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. "But under the new model, streets became a place for cars — and as a pedestrian, it's your fault if you get hit."

One of the keys to this shift was the creation of the crime of jaywalking. Here's a history of how that happened.

When city streets were a public space

Manhattan's Hester Street, on the Lower East Side, in 1914. (Maurice Branger/Roger Viollet/Getty Images)

It's strange to imagine now, but prior to the 1920s, city streets looked dramatically different than they do today. They were considered to be a public space: a place for pedestrians, pushcart vendors, horse-drawn vehicles, streetcars, and children at play.

"Pedestrians were walking in the streets anywhere they wanted, whenever they wanted, usually without looking," Norton says. During the 1910s, there were few crosswalks painted on the street, and they were generally ignored by pedestrians.

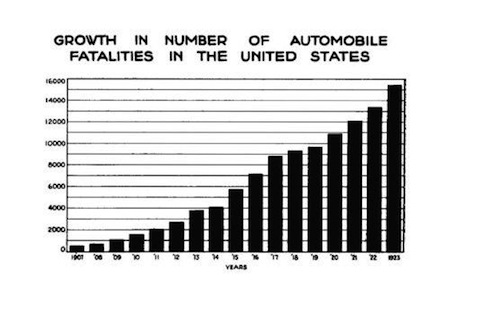

As cars began to spread widely during the 1920s, the consequence of this was predictable: death. Over the first few decades of the century, the number of people killed by cars skyrocketed.

(Courtesy of Peter Norton)

Those killed were mostly pedestrians, not drivers, and they were disproportionately the elderly and children, who had previously had free rein to play in the streets.

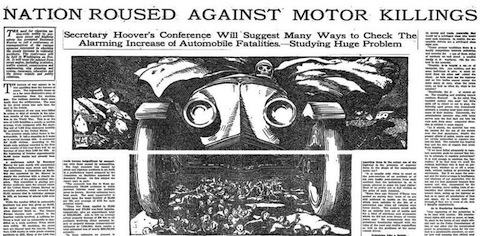

The public response to these deaths, by and large, was outrage. Automobiles were often seen as frivolous playthings, akin to the way we think of yachts today (they were often called "pleasure cars"). And on the streets, they were considered violent intruders.

Cities erected prominent memorials for children killed in traffic accidents, and newspapers covered traffic deaths in detail, usually blaming drivers. They also published cartoons demonizing cars, often associating them with the grim reaper.

The November 23, 1924 cover of the New York Times shows a common representation of cars during the era — as killing machines. (New York Times)

Before formal traffic laws were put in place, judges typically ruled that in any collision, the larger vehicle — that is, the car — was to blame. In most pedestrian deaths, drivers were charged with manslaughter regardless of the circumstances of the accident.

How cars took over the roads

In 1925 Midtown Manhattan, pedestrians compete for space with increasing automobile traffic. (Edwin Levick/Getty Images)

As deaths mounted, anti-car activists sought to slow them down. In 1920, Illustrated World wrote "every car should be equipped with with a device that would hold the speed down to whatever number of miles stipulated for the city in which its owner lived."

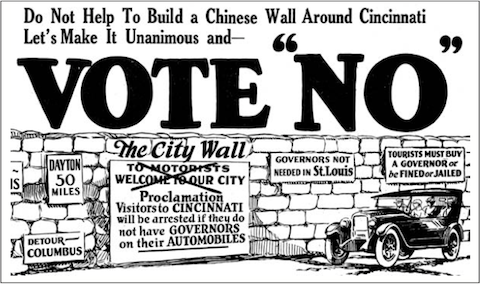

The turning point came in 1923, says Norton, when 42,000 Cincinnati residents signed a petition for a ballot initiative that would require all cars to have a governor limiting them to 25 miles per hour. Local auto dealers were terrified, and sprang into action, sending letters to every car owner in the city and taking out advertisements against the measure.

A 1923 ad in the Cincinnati Post, taken out by a coalition of auto dealers. (Cincinnati Post)

The measure failed. It also galvanized auto groups nationwide, showing them that if they weren't proactive, the potential for automobile sales could be minimized.

In response, automakers, dealers, and enthusiast groups worked to legally redefine the street — so that pedestrians, rather than cars, would be restricted.

"this is the traffic law that we're still living with today"

The idea that pedestrians shouldn't be permitted to walk wherever they liked had been present as far back as 1912, when Kansas City passed the first ordinance requiring them to cross streets at crosswalks. But in the mid-twenties, auto groups took up the campaign with vigor, passing laws all over the country.

Most notably, auto industry groups took control of a series of meetings convened by Herbert Hoover (then Secretary of Commerce) to create a model traffic law that could be used by cities across the country. Due to their influence, the product of those meetings — the 1928 Model Municipal Traffic Ordinance — was largely based off traffic law in Los Angeles, which had enacted strict pedestrian controls in 1925.

"The crucial thing it said was that pedestrians would cross only at crosswalks, and only at right angles," Norton says. "Essentially, this is the traffic law that we're still living with today."

The shaming of jaywalking

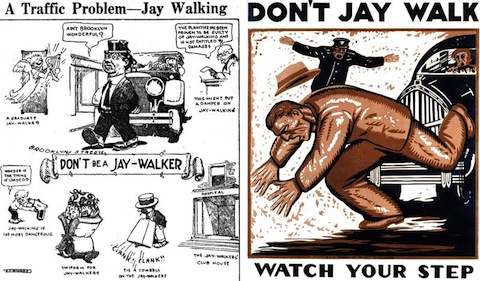

Government safety posters ridicule jaywalking in the 1920s and 30s. (National Safety Council/Library of Congress)

Even while passing these laws, however, auto industry groups faced a problem: in Kansas City and elsewhere, no one had followed the rules, and they were rarely enforced by police or judges. To solve it, the industry took up several strategies.

One was an attempt to shape news coverage of car accidents. The National Automobile Chamber of Commerce, an industry group, established a free wire service for newspapers: reporters could send in the basic details of a traffic accident, and would get in return a complete article to print the next day. These articles, printed widely, shifted the blame for accidents to pedestrians — signaling that following these new laws was important.

Similarly, AAA began sponsoring school-safety campaigns and poster contests, crafted around the importance of staying out of the street. Some of the campaigns also ridiculed kids who didn't follow the rules — in 1925, for instance, hundreds of Detroit school children watched the "trial" of a twelve-year-old who'd crossed a street unsafely, and as Norton writes, a jury of his peers sentenced him to clean chalkboards for a week.

This was also part of the final strategy: shame. In getting pedestrians to follow traffic laws, "the ridicule of their fellow citizens is far more effective than any other means which might be adopted," said E.B. Lefferts, the head of the Automobile Club of Southern California in the 1920s. Norton likens the resulting campaign to the anti-drug messaging of 80s and 90s, in which drug use was portrayed not only as dangerous, but stupid.

At a 1924 New York safety parade, a jaywalking clown is repeatedly rammed by a slow-moving Model T. (Courtesy of the Barron Collier Company, via Peter Norton)

Auto campaigners lobbied police to publicly shame transgressors by whistling or shouting at them — and even carrying women back to the sidewalk — instead of quietly reprimanding or fining them. They staged safety campaigns in which actors dressed in 19th century garb, or as clowns, were hired to cross the street illegally, signifying that the practice was outdated and foolish. In a 1924 New York safety campaign, a clown was marched in front of a slow-moving Model T and rammed repeatedly.

This strategy also explains the name that was given to crossing illegally on foot: jaywalking. During this era, the word "jay" meant something like "rube" or "hick" — a person from the sticks, who didn't know how to behave in a city. So pro-auto groups promoted use of the word "jay walker" as someone who didn't know how to walk in a city, threatening public safety.

At first, the term was seen as offensive, even shocking. Pedestrians fired back, calling dangerous driving "jay driving."

But jaywalking caught on (and eventually became one word). Safety organizations and police began using it formally, in safety announcements.

Use of the word "jaywalking" increases steeply starting in the 1920s. (Google Ngram Viewer)

Ultimately, both the word jaywalking and the concept that pedestrians shouldn't walk freely on streets became so deeply entrenched that few people know this history. "The campaign was extremely successful," Norton says. "It totally changed the message about what streets are for."