Fight for Black Voting Rights Precedes the Constitution

As Abraham Lincoln noted after the 1857 Dred Scott decision, which declared persons of African descent had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” some of those “Africans” had voted in the elections to ratify the Constitution. Lincoln went on to list five states — New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and North Carolina — where black men voted at the country’s founding. Later historians would add three more states.

Lincoln was outraged that the Supreme Court would strip citizenship from men who had been voting for generations, and he wasn’t alone. Across the North, leaders like William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, and Thaddeus Stevens expressed support for black voting rights.

These founders of the Republican Party knew what posterity has largely forgotten: that black voters by 1860 were a small but important voter bloc in those states where they could vote. They also knew that black men had been disenfranchised in state after state because they were influencing elections, and white politicians found them a convenient scapegoat.

Today, this political dynamic is familiar again: Modern Democrats for the past several decades have relied on black voters as an increasingly vital component of their electoral base. As in the antebellum period, however, opponents are attempting to deny this population the fundamental American right to vote. At its 50th anniversary this month, the Voting Rights Act and the racial equality it bestowed are under siege. This makes it all the more useful to remember that the fight for black voting rights harks back to before the signing of the Constitution — and that supporters had far more victories than is usually assumed.

There’s a comforting myth in the United States that suggests African-Americans steadily moved from absolute slavery to complete freedom following the Civil War. This, however, obscures how hard many Americans of every race had fought against racism since the Revolution. It was a struggle that went deeper than slavery and right to the core of who was an American.

Hiking while black: The untold story

Why is the American story of nature and conservation so white? Carolyn Finney uncovers a complicated history.

Most Americans assume black electoral participation was rare before the 1960s. Devotees of politics may remember that by the late 1940s there were enough black voters in cities like Chicago and New York to push Harry S Truman into modest support for civil rights. Students sometimes learn about the Radical Reconstruction of 1867 to 1877, when masses of Southern black men helped put Ulysses S. Grant in the White House and sent 16 of their own to Congress, including two senators from Mississippi. Still, free people of color prior to the Civil War — when nine out of 10 African-Americans were slaves — are generally presumed to have been poor and powerless.

Except that they weren’t. A large group of Northern founders, especially “Yankees” from New England, were deeply uncomfortable with the new-fangled racial ideology being pushed by their Southern brethren, including Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson. In Boston and New York, leaders like John Hancock and Aaron Burr actively recruited “electors of color” after the American Revolution. By James Madison’s administration, his supporters spoke derisively of black Federalists in port towns like Salem and Portland, Maine, where they began gaining minor patronage positions. In 1813, Manhattan’s black voters were blamed for Federalists retaking the State Assembly.

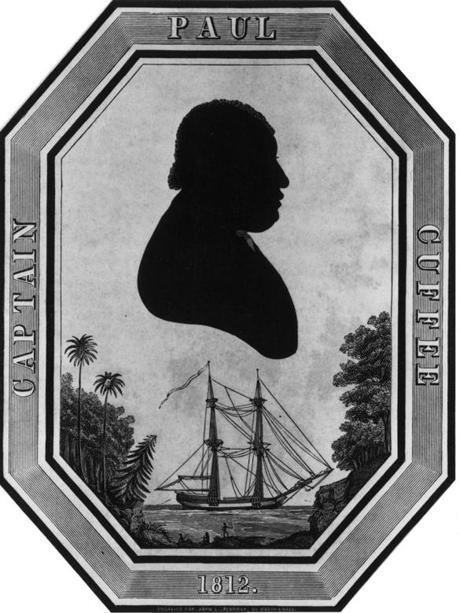

MPI/Getty Images

Captain Paul Cuffee, a freed slave, was instrumental in securing the vote for black property owners in Massachusetts.

During the Missouri Crisis in 1820, New Englanders from all parties spoke up in Congress for the equality of their black constituents. Massachusetts’ Senator Harrison Gray Otis declared, “All persons born in Massachusetts, of free parents, were citizens,” and called his state’s black men “legitimate co-proprietors with himself” of the nation. In the House, Vermont’s Rollin C. Mallary noted that his state’s constitution embraced “all of every color, whether ‘born in this country or brought from over sea’. . . . The light or shade of a countenance, which indicates an alliance with the great family of man, confers no exclusive privileges on the possessors.” A Bay State congressman, William Eustis (soon to be elected governor), hailed black soldiers’ valor during the Revolutionary War, saying, “I very much doubt . . . if there be a member on this floor from any one district in Massachusetts, whose election does not partake of the votes of these people.” A New Hampshire Senator, David Morril, listed prominent men of color, including the eminent Rev. Lemuel Haynes of Rutland, Vt. (a confidante of the state’s leading politicians), Wentworth Cheswill, who “held some of the first offices” over more than 40 years in Newmarket, near Portsmouth, and the Rev. Thomas Paul, pastor of Boston’s black Baptist Church.

The antebellum decades saw an intensifying battle over black citizenship. Voting was highly public, and how men of color voted had a demonstrable effect when the antislavery Liberty Party competed with the major parties in the 1840s: If black voters switched to the “third party,” large numbers of white abolitionists might follow them. (Although New England Whigs gave black men minor offices, the Liberty Party was the first to name them to significant party positions and put them up as candidates for office.) In the 1850s, the Republicans, anticipating the post-Reconstruction amendments, sought African-American support as one means to grow their fledging party’s base.

Ohio furnishes a dramatic example of nascent black power at the ballot box. An 1831 state Supreme Court decision declared that “mulattoes” were white for purposes of voting; later the preeminent black leader, John Mercer Langston, who was elected clerk of a town near Oberlin, declared, “Anybody that will take the responsibility of swearing that he is more than half-white, shall vote. We do not care how black he is.”

In 1855 and later, bitter Democrats charged that abolitionist Salmon Chase was elected Ohio’s governor by “negro votes,” meaning that the nearly 8,000 black men constituted a balance of power in that closely divided state. In October 1860, Democrats claimed Lincoln could only carry Ohio — and thus the Electoral College — with these supposedly illegal votes, declaring that they should be challenged before the US Supreme Court.

Indeed, the amendments passed during Reconstruction that granted citizenship to all native-born persons (including former slaves) and gave the vote to all black men were the culmination of a long struggle over what kind of country America should be. And even those great reforms were overturned by Southern Democrats for another 70 years, making a second Reconstruction necessary.

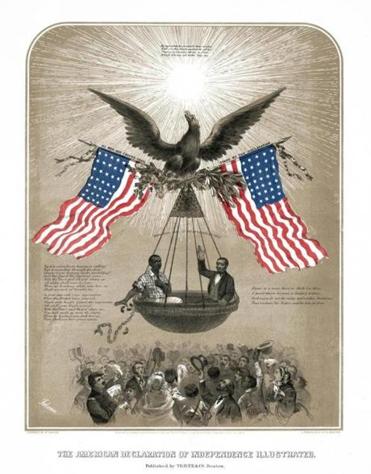

Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images

The Declaration of Independence illustrated by Dominique Fabronius circa 1861 as a call for emancipation of slaves.

The full history of black voting rights helps explain how much has been gained and how much further there is to go. The fights over who can vote are usually purely about power, and who should have it, whether it is empowering one group or depriving another — although it should be obvious that basic democratic morality should lead to empowering all, not some.

Because they vote in very high numbers, poor black people’s rights are now being targeted in the attempts to undermine the Voting Rights Act. They have upset the electoral calculus. (One thinks of Mitt Romney’s advisers telling him until late on Election Night 2012 that President Obama could not defeat him because “those people” would never turn out as they had in 2008.)

Attempts to deprive a particular group of citizenship rarely have anything to do with who is more “American” — after all, most African-Americans trace their families’ arrival to before the Revolution and are English-speaking Protestants, just like the Founding Founders.

Flashing forward to more recent events, consider Rudy Giuliani, a grandson of immigrants and a Catholic (a group repeatedly treated as irredeemably “foreign” and potentially disloyal) trying to claim authentic American-ness to bait the president. Giuliani’s aim was partisan gain, just like a WASP politician in Boston or New York baiting an Italian or Irishman a generation or two ago. Giuliani’s audiences, amplified by Fox News, likely find the prospect of black people voting distressing because they know how those people will vote, and they want to exclude them, just as in 1815 or 1915. In that sense, the past isn’t past at all — it’s the same history, answering the same question over and over again about whether or not the United States will be an authentic democracy by and for all the people.

Van Gosse is an associate professor of history at Franklin & Marshall College. His book, “We Are Americans: The Origins of Black Politics, 1790-1860,” will be published by the University of North Carolina Press next year.