Burkina Faso: Liberation not looting

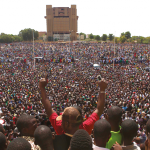

Burkina Faso enjoyed some unusual international press attention last October, following the ousting of the country’s president Blaise Campaoré by mass uprisings. As Burkina’s national assembly was due to debate extending Campaoré’s presidential term, protesters took to the streets and set fire to the assembly building.

The protests broke out shortly after the 27th anniversary of the assassination of Thomas Sankara (known as Africa’s Che Guevara) and his comrades at the hands of Campaoré on 15 October 1987.

A section of the armed forces has now taken control within the vacuum, but without a clear social programme. Elections will be held next November. Campaoré has been banned from participating and he has fled to Côte d’Ivoire with the aid of the French. But the popular movements that took to the streets have been neither defeated nor diverted, and recent protests forced a further resignation, this time from the interim government.

This latest turn in Burkina Faso’s history provides an illustration of two deeply contrasting forms of ‘development’. One is inspired and driven by the desire for self-determination and development of the country’s productive forces, which implies liberation, emancipation, hope and human progress. But in practice, the country’s development has fallen short of these fine goals, particularly since the emergence of neoliberalism, actually leading to the opposite: a surrender to the looting requirements of parasitic neoliberal capital.

The République de Haute-Volta (Upper Volta), as it was once known, was once part of the French Union; it was given ‘independence’ from France in 1960. At that time the tiny impoverished country was grossly underdeveloped and unable to feed its population. It had an illiteracy rate of 90 per cent, the world’s highest infant mortality rate (280 deaths for every 1,000 births), inadequate basic social services, one doctor per 50,000 people, and an average yearly income of $150 per person.

Extraordinary revolution

Following a series of coups that eventually led Thomas Sankara and his comrades to power in 1983, an extraordinary revolution was unleashed in the country involving the mobilisation of the Burkinabé citizenry. In the space of just four years, Burkina Faso became self-sufficient in food, its infant mortality rate halved, school attendance doubled, 10 million trees were planted to halt desertification and wheat production doubled.

Land and mineral resources were nationalised, railways and infrastructure constructed, and 2.5 million children were immunised against meningitis, yellow fever and measles. Nearly 350 medical dispensaries and schools were constructed across the country by communities.

Female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy were outlawed. Indeed, there have been few African leaders who have been so committed to the emancipation of women as Sankara. ‘We do not talk of women’s emancipation as an act of charity or out of a surge of human compassion,’ he said. ‘It is a basic necessity for the revolution to triumph.’

Burkina Faso was marked by the almost complete absence of foreign aid agencies and development NGOs. Sankara did not ask for aid – on the contrary, he shunned it. Moreover, he argued that the large foreign debt his country was paying was odious and therefore should be repudiated.

He told the UN: ‘The debt cannot be repaid, first because if we don’t repay, lenders will not die. That is for sure. But if we repay, we are going to die. That is also for sure. Those who led us to indebting ourselves had gambled as if in a casino. As long as they had gains, there was no debate. But now that they suffer losses, they demand repayment. And we talk about crisis. No, Mr President, they played, they lost – that’s the rule of the game, and life goes on.’

This meant that cotton production was no longer directed to export to earn dollars to service debt but instead was used to support a thriving Burkinabé textile industry. The renaming of the country as Burkina Faso (‘the land of the upright people’) was symbolic of the transformation from ‘a land of beggars’, so beloved of the development industry, to the land of dignified human beings who determine their own history.

Sankara’s assassination at the hands of Blaise Campaoré brought about a reversal of all the gains of that short period. It enabled neoliberal capitalism to reassert its hegemony over the country. Under Campaoré, the country quickly returned to the conditions of the former République de Haute-Volta.

Cotton was once again grown for export, comprising 30 per cent of Burkina Faso’s per capita GDP of $1,500 (one of the lowest in the world). Today, it is classified as a highly indebted poor country, with more than 80 per cent of its population living on less than $2 a day, and nearly 50 per cent on less than $1 a day. Infant mortality rates have been increasing. Literacy levels have fallen back to around 12 per cent, with less than 10 per cent of primary scholars reaching secondary school.

In contrast to the program of ‘land to the peasant’ initiated under Sankara, Campaoré’s policies gave land to the elite. Corruption became an integral part of the economy, with millions syphoned off from aid and handouts from mining companies. In return a number of transnational mining corporations have been allowed to excavate gold and other minerals, with almost no benefit to the population at large. Privatisation of water and other utilities has been the order of the day. And the regime has not been averse to using violence and assassinations to deal with its opponents.

The fundamental changes undertaken by Campaoré were to enable capital to transform the economy from being independent, productive and serving the needs of the population, to one in which accumulation took place primarily through the extraction of rent and the amputation of natural resources.

Parasitic NGOs

In this context the NGOs have also come in, taking on parasitic form, living off this ‘rentier economy’ as ‘white saviours’, diverting attention from the looting of wealth to defining the problem as one of ‘poverty’, not power. Growth in the presence of the transnational development NGOs and an exponential proliferation of their local Burkinabé counterparts (all dependent on foreign aid and numbering in the hundreds) has been a feature of the Campaoré regime.

Oxfam Québec’s involvement in Burkina Faso, for example, escalated after Campaoré took power in 1987. More recently, Plan Canada received millions of dollars from the Canadian government to enable it to collaborate with the transnational gold mining corporation, Iamgold, to provide services around the gold mines of Burkina Faso that would make the corporation appear less pernicious in its exploitation of the land and its people.

What we see here is an increasingly common example of the transition of development NGOs to becoming the handmaidens of neoliberal development and in particular of transnational corporations. They have evolved into an integral part of neocolonial rule, providing services to native populations that the state will not. In so doing, they are complicit in a form of violence, serving to dominate the mental universe of the African and ‘the control, through culture, of how people perceived themselves and their relationship to the world’, as Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o puts it.

With the fall of Campaoré, it is unclear what is likely to happen next in Burkina Faso. Thomas Sankara’s name is once again on people’s lips, a confirmation that you can kill a person but you can’t kill an idea. What these movements will need is support to rekindle the ideas behind the Sankara revolution. For that, they need not aid, nor development, but solidarity.

Firoze Manji is the director of the Pan-African Baraza in Nairobi and the founder of Pambazuka News