As Encryption Spreads, U.S. Grapples With Clash Between Privacy, Security

For months, federal law enforcement agencies and industry have been deadlocked on a highly contentious issue: Should tech companies be obliged to guarantee government access to encrypted data on smartphones and other digital devices, and is that even possible without compromising the security of law-abiding customers?

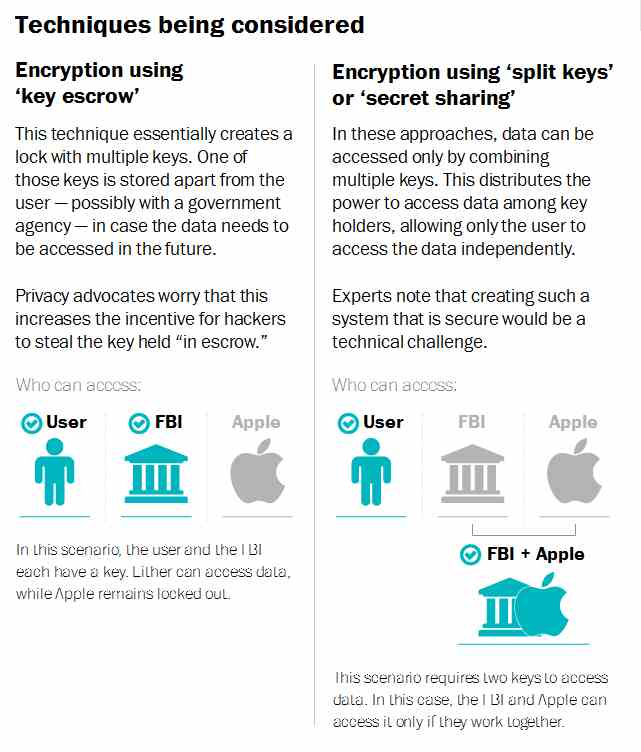

Recently, the head of the National Security Agency provided a rare hint of what some U.S. officials think might be a technical solution. Why not, suggested Adm. Michael S. Rogers, require technology companies to create a digital key that could open any smartphone or other locked device to obtain text messages or photos, but divide the key into pieces so that no one person or agency alone could decide to use it?

“I don’t want a back door,” Rogers, the director of the nation’s top electronic spy agency, said during a speech at Princeton University, using a tech industry term for covert measures to bypass device security. “I want a front door. And I want the front door to have multiple locks. Big locks.”

Law enforcement and intelligence officials have been warning that the growing use of encryption could seriously hinder criminal and national security investigations. But the White House, which is preparing a report for President Obama on the issue, is still weighing a range of options, including whether authorities have other ways to get the data they need rather than compelling companies through regulatory or legislative action.

The task is not easy. Those taking part in the debate have polarized views, with advocates of default commercial encryption finding little common ground with government officials who see increasing peril as the technology becomes widespread on mobile phones and on text messaging apps.

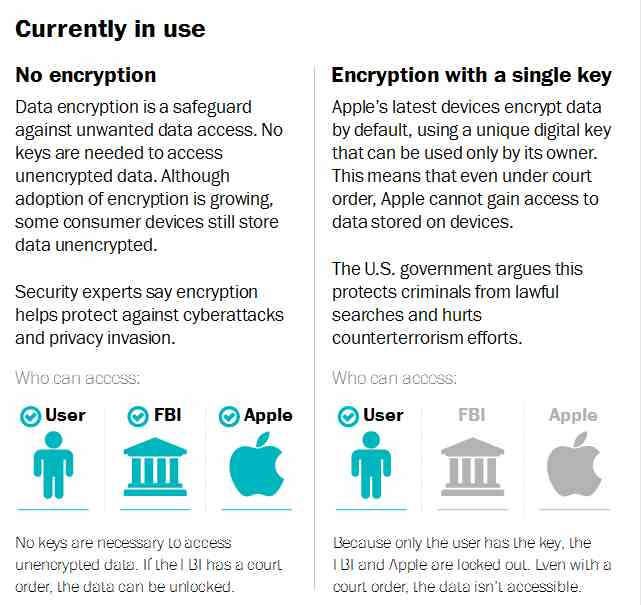

Apple catalyzed the public debate in September when it announced that one of the world’s most popular smartphones would come equipped with a unique digital key that can be used only by its owner. Even if presented with a warrant, Apple could no longer unlock an iPhone that runs its latest operating system.

Hailed as a victory for consumer privacy and security, the development dismayed law enforcement officials, who said it threatens what they describe as a centuries-old social compact in which the government, with a warrant based on probable cause, may seize evidence relevant to criminal investigations.

“What we’re concerned about is the technology risks” bringing the country to a point where the smartphone owner alone, who may be a criminal or terrorist, has control of the data, Deputy Assistant Attorney General David Bitkower said at a recent panel on encryption hosted by the nonprofit Congressional Internet Caucus Advisory Committee. That, he said, has not been the “standard American principle for the last couple of hundred years.”

Tech industry officials and privacy advocates take a different view. “I don’t believe that law enforcement has an absolute right to gain access to every way in which two people may choose to communicate,” said Marc Zwillinger, an attorney working for tech companies on encryption-related matters and a former Justice Department official. “And I don’t think our Founding Fathers would think so, either. The fact that the Constitution offers a process for obtaining a search warrant where there is probable cause is not support for the notion that it should be illegal to make an unbreakable lock. These are two distinct concepts.”

The increasing use of encrypted storage extends well beyond the iPhone or the similar option that Google offers — though not by default — on new versions of its Android operating system. Windows and Apple offer simple settings to encrypt the contents of personal computers, and several cloud storage companies encrypt the data they host with keys known only to their customers.

The Obama administration says it is not seeking to weaken the security tools themselves. “There’s no scenario in which we don’t want really strong encryption,” President Obama said in an interview with the online tech news outlet Re/Code in February. “I lean probably further in the direction of strong encryption than some do inside of law enforcement. But I am sympathetic to law enforcement, because I know the kind of pressure they’re under to keep us safe. And it’s not as black and white as it’s sometimes portrayed.”

Until Rogers’s remarks, U.S. officials had declined to say how they believed they could guarantee government access to a locked device without introducing security flaws that others could also find.

Academic and industry experts, including Yahoo’s chief of information security, Alex Stamos, say law enforcement is asking for the impossible. Any means of bypassing encryption, they say, is by definition a weakness that hackers and foreign spy agencies may exploit.

The split-key approach is just one of the options being studied by the White House as senior policy officials weigh the needs of companies and consumers as well as law enforcement — and try to determine how imminent the latter’s problem is. With input from the FBI, intelligence community and the departments of Justice, State, Commerce and Homeland Security, they are assessing regulatory and legislative approaches, among others.

The White House is also considering options that avoid having the company or a third party hold a key. One possibility, for example, might have a judge direct a company to set up a mirror account so that law enforcement conducting a criminal investigation is able to read text messages shortly after they have been sent. For encrypted photos, the judge might order the company to back up the suspect’s data to a company server when the phone is on and the data is unencrypted. Technologists say there are still issues with these approaches, and companies probably would resist them.

White House aides aim to report to Obama this month, though the date could slip. “We want to give the president a sense of what the art of the possible is,” said a senior administration official who requested anonymity because he was not authorized to speak on the record. “We want to enable him to make some decisions and strategic choices about this very critical issue that has so many strategic implications, not just for our cybersecurity but for law enforcement and national security, economic competitiveness overseas, foreign relations, privacy and consumer security.”

A central issue in the policy debate is trust, said Lance J. Hoffmann, founder of George Washington University’s Cyberspace Security Policy and Research Institute. “It’s who do you trust with your data? Do you want to default to the government? To the company? Or to the individual? If you make a hybrid, how do you make the trade-off?”

The odds of passing a new law appear slim, given a divided Congress and the increased attention to privacy in the aftermath of leaks by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. There are bills pending to ban government back doors into communications devices. So far, there is no legislation proposed by the government or lawmakers to require Internet and tech firms to make their services and devices wiretap-ready.

“There is zero chance of any domestic restrictions on encryption absent a catastrophic event which clearly could have been stopped if the government had been able to break some encryption,” said Michael Vatis, a senior Justice Department cyber-official in the Clinton administration and a partner at Steptoe and Johnson. “That is the only way I could even imagine any restriction on encryption being passed by Congress.”

Even if Congress passed such a law, it could not bind device-makers and software engineers overseas. Privacy advocates said strong encryption technology is now sufficiently widespread that it is effectively beyond the reach of government control.

That is what Britain is discovering: It has a law that would require any telecom company to give the government access to data, but the law cannot be used to compel foreign firms that lack encryption keys to create them, legal experts said.

The debate in some ways harks back to the “cryptowars” of the 1990s, when the Clinton administration proposed having the government hold a decryption key “in escrow” for law enforcement seeking to wiretap encrypted voice calls. The proposal had its origins in the nuclear bunker where, to avoid the risk of a rogue actor launching a nuclear weapon, the government required two people, each holding part of a key, to put their parts together to unlock the weapon.

The government lost, primarily on policy grounds. “Fundamentally, what bothered me, and I think many people, is the notion that you don’t have a right to try to protect your communications but are forced to trust a third party over which you have no control,” said Whitfield Diffie, a pioneer of public-key cryptography who was part of the opposition that killed the proposal.

The debate now differs in at least one key respect: its global reach. Today, demand for data security transcends borders, as does law enforcement’s desire to obtain the data. Countries including the United Kingdom, Australia and China have passed or are contemplating laws seeking government access to communications similar to that sought by U.S. authorities.

The split-key approach floated by Rogers is a variant on that old approach and is intended to resolve some of the policy objections. Storing a master key in pieces would reduce the risk from hackers. A court could oversee the access.

But some technologists still see difficulties. The technique requires a complex set of separate boxes or systems to carry the keys, recombine them and destroy the new key once it has been used. “Get any part of that wrong,” said Johns Hopkins University cryptologist Matthew Green, “and all your guarantees go out the window.”

Officials say that if default encryption of e-mails, photos and text messages becomes the norm without the company holding a key, it could, as Bitkower said, render a warrant “no better than a piece of paper.”

Neither Bitkower nor FBI Director James B. Comey, who also has been vocal about the problem, has been able to cite a case in which locked data thwarted a prosecution. But they have offered examples of how the data are crucial to convicting a person.

Bitkower cited a case in Miami in December in which a long-haul trucker kidnapped his girlfriend, held her in his truck, drove her from state to state and repeatedly sexually assaulted her. She eventually escaped and pressed charges for sexual assault and kidnapping. His defense, Bitkower said, was that she engaged in consensual sex. As it turned out, the trucker had video-recorded his assault, and the phone did not have device encryption enabled. Law enforcement agents were able to get a warrant and retrieve the video. It “revealed in quite disturbing fashion that this was not consensual,” Bitkower said. The jury convicted the trucker.

Officials and former agents say there will be cases in which crimes will go unsolved because the data was unattainable because only the phone owner held the key. “I just look at the number of cases I had where, if the bad guy was using one of these devices, we never would have caught him,” said Timothy P. Ryan, a former FBI supervisory special agent who now leads Kroll Associates’ cyber-investigations practice.

But, he said, “I think the genie’s out of the bottle on this one.”

Some experts say the challenge of device encryption may be diminished if law enforcement can compel a suspect to unlock his phone. But, they add, doing so may raise Fifth Amendment issues of self-incrimination in some cases.

Encryption of phone calls is the harder challenge and the one that agencies such as the NSA, which needs to hear what targets are saying rather than gather evidence for a prosecution, are more concerned about. Brute-force decryption is difficult and time-consuming, and getting covert access through manufacturers requires a level of specificity and access that is not often available, intelligence officials say.

“The basic question is, is it possible to design a completely secure system” to hold a master key available to the U.S. government but not adversaries, said Donna Dodson, chief cybersecurity adviser at the Commerce Department’s National Institute of Standards and Technologies. “There’s no way to do this where you don’t have unintentional vulnerabilities.”