The Poems of Amiri Baraka

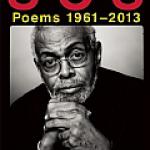

S.O.S.: POEMS 1961 - 2013 BY AMIRI BARAKA, EDITED BY PAUL VANGELISTI

Grove Press

ISBN: 978-0802123350

S.O.S. Poems 1961-2013 is a broad selection of arguably the best of now-deceased Amiri Baraka's poetry. Editor Paul Vangelisti has brought together the complete contents of two previous collections he edited, Transbluesency: the Selected poetry of Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones 1961-1995 and Funk Lore, along with a generous portion of Baraka's late work, spanning the years 1996-2013. Baraka approved of the selections made for the earlier volumes, but Vangelisti was on his own selecting the later work. He demonstrates an excellent sense, however, for understanding the finer nuances of Baraka's poems, and this final section impeccably demonstrates how strong Baraka's skills as a poet remained to the very end of his life.

The closing lines of the final poem in the book "Ballad Air & Fire," with its dedication for Sylvia or Amina (Baraka's wife), fittingly encapsulate Baraka's passionate embrace of a life dedicated to being a poet first and foremost:

to have been together

and known you, and despite our pain

to have grasped much of what joy exists

accompanied by the ring and peal of your

romantic laughter

is what it was about, really. Life.

Loving someone, and struggling

Baraka spent a lifetime writing highly political, engaging work without ever shying away from also allowing for its presentation embedded within the experimental and challenging nature of poetics to which he was drawn. Yet, without crossing over into pathetic cliché, there are a number of low-key yet commanding instances of love poems to Amina scattered throughout the late work. These are poems which in their formal, near philosophical reflection upon the experience of Love, call to mind the French troubadours, whose work was deeply influential on other poets of Baraka's generation, and one-time members of his social milieu, such as Paul Blackburn and Robert Creeley, along with the Modernist American poet William Carlos Williams's own late-in-life love poem to his wife, Flossie, "Asphodel, That Greeny Flower."

Baraka dwells over the rewards of having shared his life with a lover, finding solace in its place for him in the vast scheme of things:

hear yourself thinking about some person other than you

and then look up and yes there will be some other person

some closeness and echoed tenderness, that makes us more than dots

under the far away, that makes us more than split seconds of

light

("Chamber Music")

And he probes the larger meaning behind the mysteries of how Love teaches its lessons, witnessing its force as powerfully present as any other he's known:

As weird as it is, Love is a form of knowledge, and any persons

you say you love know

you like you know them. My wife, Amina, is like that, for me,

the heartbeat, like my

own, and what it is is what it says and what it reaches is what it

touches.

("Big Foot")

Recognizing the seeming impossibility of its shared reality, and yet how abiding a reassurance it nonetheless remains:

We are what we can be together never enough

Though without each other we don't know ourselves

("Note to Sylvia Robinson from when I saw her walking through the projects in 1966")

Before his life with Amina, Baraka lived through times when his sense of self was far more fractured. The degree to which his poetry reveals his remarkable ability to endlessly endeavor to seek out a future self-identity and accompanying philosophy is in large part an accurate measure of his striking accomplishment. Baraka never ceased to be critically engaged with his individual personal development and to pour that struggle into his poems. His writing is thoroughly self-reflective, an outgrowth of his extensive readings in literature and philosophy. While in the U.S. Army he had taken advantage of his assignment as a night librarian on an isolated base overseas to begin his self-education by reading the avant-garde Modernist literature that naturally called out to his rebellious sensitivity. Soon he was an active participant in the exploding scene in American poetry during the 1950s, happening not in the university but rather out on the street, alive to the harmonies and demands of the life found there.

In The Dead Lecturer, his second collection of poetry published while he still publicly identified by his birth name, LeRoi Jones, the poet declares "let my poems be a graph / of me" ("Balboa, The Entertainer"). Here he echoes his poet-peer Philip Whalen's description of his own poems as "a picture or graph of the mind moving." Baraka/Jones appeared notably as the only African American alongside Whalen and a host of likeminded associates of their generation in Don Allen's anthology The New American Poetry: 1945-1960. Baraka/Jones's own work and personal friendships at the time bridged several of the "schools" of poetry represented in Allen's book: the Beats, New York School, and Black Mountain. During this period, Baraka/Jones was smack in the center of the heady midst of the poetry scene in New York City's Lower East Side, editing the Floating Bear poetry newsletter with Italian-American poet Diane Di Prima, with whom he was having an extramarital affair and frequently engaging in drunken late night parties with white poets. His poetry records inner struggle and dissatisfaction:

I am inside someone

who hates me. I look

out from his eyes. Smell

what fouled tunes come in

to his breath. Love his

wretched women.

("An Agony. As Now")

As the 1960s progressed and his political consciousness became increasingly radicalized along racial lines he dramatically and abruptly broke away from all his associations with whites, leaving his interracial marriage to poet Hettie Jones and moving up to Harlem and later to Newark, New Jersey. His self-identity was radically changing:

When they say, "It is Roi

Who is dead?" I wonder

Who will they mean?

("The Liar")

LeRoi Jones became Amiri Baraka, adding his vocal support as poet, playwright, novelist, and radical thinker to the Black Power movement and the ongoing struggle for African American equality. Throughout his life Baraka continually advanced in his political thought, ever deepening his commitment to poor disadvantaged people of color. As he progressed from a Black Nationalist separatist philosophy to one of Militant Marxism, which lead him in turn eventually to an international Socialism, his involvement always remained focused upon his local community. Everything Baraka experienced encouraged his belief in the absolute validity that for African American communities: "This was always, and remains / a foreign land" ("Stellar Nilotic").

Along with many other African-American writers and intellectuals, Baraka recognized that the racial divide within the cultural consciousness split the individual self-consciousness as well. As a poet he readily identified with French poet Arthur Rimbaud's famous statement that "JE est un autre" ("I is Another"), which never left him, being quite evident in his poem "Small Talk in the Mirror" from the late work:

There is some kind of skeleton of ignorant greed

Clutching our ears knows mouth where we breathe

Not you, the other then, the one

Who follows, the one who wont acknowledge

The teeth in your tongue, the stomach in every song

You have sung.

Baraka admirably held himself to account as much as anybody else. Just as he would never let himself forget the injustices, historical as well as contemporary, waged upon African-American people, he never let white America forget either. His poem "In the Tradition" is a fierce indictment and reminder of the strength of African-American resilience by way of artistic expression to centuries of oppression and disastrous public policies in the Western hemisphere. It is also a hilariously thrilling talking back to the euro-centric, bigoted blindness displayed by the American musical community of predominantly white critics and would-be connoisseurs claiming a "tradition" for their own while feigning ignorance of how clearly it derives solely from out African American music. For Baraka, jazz, "nigger music," is clearly the single greatest contribution to defining any worthwhile sense of "American music."'

We are the composers, racists & gunbearers

We are the artists

Don't tell me shit about a tradition of deadness & capitulation

of slavemasters sipping tea in the parlor

while we bleed to death in fields

tradition of cc rider

see what you done done

dont tell me shit about the tradition of slavemasters

& henry james I know about it up to my asshole in it

dont tell me shit about bach mozart or even ½ nigger

beethoven

get out of europe

come out of europe if you can

cancel on the English depts this is america

north, this is America

where's yr american music

gwashington won the war

where's yr american culture southernagrarians

academic aryans

penwarrens & wilburs

say something American if you dare

if you

can

where's yr american

music

nigger music?

Later in the poem he mockingly urges white America:

you better go up in appalachia

and get some mountain some coal mining

songs, you better go down south in our land

& talk to the angloamerican national minority

they can fetch up a song or two, country & western

could save you from looking like saps before the world

Baraka ends the poem sounding off with a righteously inspired curse:

Sing!

Fight!

Sing!

Fight!

Sing!

Fight! &c. &c.

Boosheee dooooo doo

Doooo dee doooo

Doooooooooo!

DEATH TO THE KLAN!

In 1982 when this poem was first published this closing may have sounded predictably over-determined and expected from Baraka. Coming out of the 1970s, much of the country felt as if the Black Power movement, along with similar social movements of struggle, had finally been more failure than success but nonetheless racial issues were often taken to be a settled matter. Of course Baraka never felt this to be the case. However, in light of the recent media spotlight brought upon the ongoing frequency of racial profiling by police departments throughout the country and the disparity of incarceration rates between whites and blacks, combined with the rash of high profile police murders of unarmed young black men, the line sounds as prescient as ever. The Klan as such may not appear publicly active yet the corrupt beliefs driving its core principles are very much at play throughout American society.

Baraka's code words for whites, along with those blacks and others who he witnesses sharing in any racist agenda, include: ghosts, the dead, corpses, vampires, and heathens. The latter he mercilessly skewers in a later collection of satirically drenched poems entitled Heathens:

Heathen Bliss

To be alive

& Ignorant.

Since Baraka saw his poems as "hot serenades / to keep the ghosts away" ("Ars Gratia Arts") he regularly utilized them as a means for publicly attacking and shaming those politicians responsible for social policies that resulted in the further degradation of people on the basis of race and class. These politicians often happened to be Republican Presidents:

The word / BUSH // Mean // DUMB // MOTHER FUCKER

("Lowcoup Linguistic")

My poetry, then,

as always been aimed at destroying ugly shit.

So why, Ronald Reagan, shd you get away?

("Ars Gratia Artis")

FOR BUSH 2

The Main Thing

Wrong

w/ You

is

You ain't

in

Jail

Baraka had no time for being politically correct or on the "right side" of any argument. He called it as he saw it. Democrat or Republican, black or white, if he didn't see the support as being there for disadvantaged citizens of color he unleashed his fury.

Whether you speak Spanish or Greek whether it comes out of

Christies mouth or Booker's, Bloomberg or some other Freak.

This the new anti fascist war we must fight, Against the rule of

The Corpses. The Corporate Dictatorship forming in front of

Our eyes.

("What's That Who is this in Them Old Nazi Clothes? Nazi's Dead")

"Christies mouth" is New Jersey governor and potential Republican candidate for president in 2016 Chris Christie; "Booker's" is former mayor of Baraka's hometown Newark ("New Ark") and now U.S. Senator Corey Booker, who Baraka describes in another of his poems "Got Any Change" as "a Negro / Ghoul, a sepia Lieutenant Nazi," "the May Whore," "Ghost brain / In a rubber brown / 'Black Man' costume"; "Bloomberg" is billionaire Michael Bloomberg whose public policies as mayor of New York City attended to his billionaire interests. In a superbly ironic twist of fate, Baraka's son Ras was elected mayor in Newark to replace Booker. There's a charming photo from shortly after his taking office of Ras Baraka and his crew sitting down with Governor Christie and his crew where the tension visibly oozes out from under the stern-faced alabaster veneer of the hulking "corpse" of the Governor.

Baraka was no stranger to scandal. He found himself stripped of the New Jersey Poet Laureateship for the following lines from his poem "Somebody Blew up America," written in response to the attacks of Sept 11, 2001:

Who knew the World Trade Center was gonna get bombed

Who told 4000 Israeli workers at the Twin Towers

To stay home that day

Why did Sharon stay away?

If read in context of the long poem in which the lines appear, it is difficult to understand the charges of anti-Semitism subsequently flung at Baraka. The attacks against him were as absurd as they were abundant. Baraka clearly adopts the role of poet-as-vatic in this poem as he had done in so many previous. The repeated refrain of "who" used at the beginning of lines throughout the poem: "Who say they God & still be the Devil"; "Who? Who? Who?"; "Who own the oil / Who do no toil"; "Who put the Jews in ovens, / and who helped them do it" is intended to be heard as an Owl's hoot "Like an Owl exploding / In your life in your brain in your self" and Baraka clearly states in the poem with whom he's laying blame. The culprit is much larger than any single nation or religion:

Who make dough from fear and lies

Who want the world like it is

Who want the world to be ruled by imperialism and national

oppression and terror violence, and hunger and poverty.

The media's maelstrom surrounding the absolute refusal to even attempt to read a poem as a poem came as little surprise to Baraka. At the height of his Black Nationalism phase, a judge sent him to jail on a trumped up charge of gun possession upon the basis of his having written a poem about killing whites. The judge argued in his sentencing that the poem was indeed the equivalent of a physical act. If he had written it, he might as well of gone into the streets and acted it out.

Baraka believed that in poetry there's no room for niceties. He quickly tired of such faux politesse. As he asks of the unnamed poet(s) addressed in "The Terrorism of Abstraction," why bother with writing a poem if you aren't fully committed to the art:

Why lie an "I" & vanish

Into parsed diction. Why

Enhance an empty place

With fantasy furniture

& say it is the truth?

Why not tell us something

Other than the sound effects

Of impotent evasion?

Why make believe poetry

Is about arrogant pretense

& social denial. Why

Try to trick us you can sing?

By the end of his long and productive life Baraka hadn't the time for fakery. He knew the score. In one of his late masterpieces, "Fashion This, From the Irony of the World," he announces himself "I the undaunted Laureate of the place" and leaves no doubt where he's coming from:

I speak with the rage of Angels

Them that be with Marx.

I speak with the clarity and inferno of the necessary

Like my man John on Patmos

Baraka's poetry is worth both study and celebration because of the readily apparent beauty, intense with its balancing of the devastating and the heroic as experienced in everyday reality:

That's why we are the blues

ourselves

that's why we

are the

actual

song

So dark & tragic

So old &

Magic

that's why we are

the Blues

our Selves

("Funk Lore")

The only blemish upon S.O.S. is how much Vangelisti's preface to this new collection is merely a restatement of his foreword to Transbluesency. Little attempt was made to rework much of that material; there are just a few additional remarks concerning the later work. It would have been much more valuable to leave the previous foreword as is and offer something entirely fresh as a preface for S.O.S. However, this volume appeared right on the heels of Baraka's passing, so publication was likely well ahead of Vangelisti's writing schedule. A lengthier critical appreciation would have nicely enhanced the volume, as would have some notes regarding individual collections, if not individual poems. But the important thing is that Baraka's work is presented in the copious manner it well deserves, allowing for it to fill room after room.