Can Auto Shed Its Tiers?

https://portside.org/2015-07-26/can-auto-shed-its-tiers

Portside Date:

Author: Alexandra Bradbury

Date of source:

Labor Notes

Eight years after accepting a drastic two-tier system of wages and benefits—and nearly a decade since the first tier got a raise—the United Auto Workers are bargaining with the Big 3 automakers.

Talks began July 13 with a ceremonial handshake. It’s the first contract expiration since Michigan’s “right to work” law went into effect, which means disgruntled members in the union’s most populous state could jump ship.

The Big 3 bargain at separate tables. Traditionally, as talks develop, the union will zero in on one to settle with first. The others generally fall in line. Separate local bargaining, already begun, covers non-economic issues like work schedules.

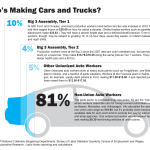

Together the contracts cover about 137,000 workers—including a lower-wage second tier that makes up 45 percent of the workforce at Chrysler, 25 percent at Ford, and 20 percent at General Motors, according to the Center for Automotive Research.

Tier 1 production workers, hired before the 2007 deal, have been frozen at $28.69 ever since. Gone is the cost-of-living raise (COLA) that used to link wages to inflation. They’ve also been hit by concessions on holiday pay and overtime.

The top tier has lost more than $4 an hour, calculates Detroit-area Chrysler worker Bill Parker, former president of UAW Local 1700.

Meanwhile Tier 2 production workers—anyone hired since 2007, though they may do the same jobs—top out at $19.28, with an inferior health plan and a 401(k) instead of a pension.

MIND THE GAP

The second tier was originally supposed to be capped at 20 percent of each workforce. To comply, this spring Ford moved 500 second-tier workers up to the higher rate. But for GM and Chrysler, the caps were lifted as part of the government bailout deals.

And despite the employers’ recovery, now that it can’t be un-bailed out, Chrysler makes no secret of its desire to phase out the top tier altogether. CEO Sergio Marchionne told reporters last year he wants to make first-tier workers “a dying class.”

“Why not let the CEO class be a dying class?” counters Asar Amen-Ra, a 20-year employee at the Chrysler subsidiary Mopar in Center Line, Michigan.

From his point of view, Amen-Ra says, “the point of bargaining this year should be to make all UAW employees whole, from the time we made all those concessions.” He means both the first and second tiers—and the union’s unacknowledged third tier, outsourced workers.

In his plant, janitors now work for a contractor, Caravan Facilities Management. And though they’re UAW members too, they make just $11-$14.88.

“Those used to be good jobs,” Amen-Ra says, the kind you’d get with 25 years’ seniority, so you could “spend your last years doing so-called easier work… We want those workers to have a livable wage, and we want those jobs back in-house.”

The Wall Street Journal claimed in May that the union is considering creating an official third tier to get the companies to “insource” this sort of currently outsourced work in the plants—“low-skilled jobs, such as organizing auto parts in bins”—but for even lower wages, $10-15.

Yet another unacknowledged tier is all the work that’s been spun off or outsourced over the years to lower-wage suppliers, union or not.

Parker says since the 1990s he’s been fruitlessly pointing out to union officials how the industry’s changed from the days when Big 3 plants “brought in iron ore and rubber, and drove out a car. Now everybody buys tires from somebody else, and seats from somebody else… The union is not looking at what any of that means.”

“We’re making a mistake if we limit the struggle over two-tier to just getting parity inside the Big 3,” agrees Ford retiree Ron Lare.

WHERE’S THE STRATEGY?

So what’s the plan to win back all that’s been lost? As with past contracts, the international union isn’t running any contract campaign. There are no petitions, sticker days, rallies, or pickets.

In the rare case where those activities are happening, they’re locally driven—like in Local 551, where Scott Houldieson was recently elected vice president.

In an online survey, “we’re asking members to give their most important issues in the upcoming contract negotiations,” said Houldieson, an electrician at the Ford Assembly Plant in Chicago.

“We’re also asking them to update their info so that we have everybody’s cell phone numbers and email addresses—so that if we do go on strike, we would be able to get hold of everybody and give them their assignment.

“Also we’ve ordered 6,000 buttons that say ‘I’m Saving to Strike for a Better Contract,’ so we’ve been passing those out.”

Amen-Ra and a few co-workers have been preparing by studying the union’s bargaining history. “For some reason, the UAW always extends the contract,” he says.

He’d rather the union treat the September 14 expiration as a strike deadline, following the example of the Canadian Auto Workers (now Unifor). “When they set a deadline, they actually go out on strike, they don’t play games,” Amen-Ra says, “and we need to do the same thing.”

Trouble is, “the union doesn’t have a strategy of its own,” says Parker. “Its strategy is to help the companies survive.”

The union’s bargaining convention in March was tightly controlled. A resolution from leadership that called for “bridging the gap” between tiers was vague—but activists couldn’t muster the votes to make eliminating the gap an explicit bargaining priority.

“The way they’re talking with members isn’t a way to talk about waging a struggle,” Parker says. “It’s a way to talk about justifying very small gains.”

WRONG WAY TO CLOSE GAP

How small? The automakers are telling the press they want to cut costs or keep them steady. So if they also say they’re interested in closing the gap between tiers, they don’t mean that in a good way.

In fact, the employers also say they want to cut health care costs. UAW President Dennis Williams has hinted at the possibility of moving current employees into the underfunded, union-run trust fund, the VEBA, that now covers retirees.

There’s also been press noise about cutting health care benefits to avoid the so-called Cadillac tax, though Houldieson suspects that’s “more a tactic to keep people off balance.” His statement from Ford shows his first-tier plan is far below the threshold that would make the tax kick in.

And in the days leading up to bargaining, the companies have been rattling their sabers by threatening job cuts. GM announced it’s investing $350 million in a Mexican plant; Ford said it will move two compact cars out of its Michigan Assembly Plant to an unspecified location outside the U.S.

On the other hand, the Big 3 may recognize they’ve got to throw the union a bone if they don’t want to kill off their partner in production, now that Michigan members could quit the union.

“You would think that would put a pressure on the International to negotiate a better deal,” says Wendy Thompson, a retired local president from GM spinoff American Axle, “but they may just be able to camouflage it.

“They like to put forward the public face that they’re not worried about [right to work]. If they’re not, they should be.”

It’s unlikely the companies would accept an unpredictable new cost like restoring the COLA, warns Chrysler retiree Amy Bromsen. She says it’s more likely they’ve budgeted a set amount that the union will distribute to try to placate each member constituency.

Thompson worries the union’s plan for two-tier may turn out to be sleight of hand—perhaps along the lines of what happened last year at a Lear plant in Hammond, Indiana, that supplies seats to Ford.

That local declared it had ended two-tier when the whole plant moved to a $16.50-$21.58 scale. The catch: some jobs and workers were moved to Lear II, a new plant with a lower scale, $12-$15.25.

“There are so many ways they can say they have solved the two-tier problem when they haven’t really done so,” says Thompson.

The Autoworker Caravan network of activists is planning a speakout in Detroit on August 23.

CORRECTION: Asar Amen-Ra is a 20-year employee, not 40-year.