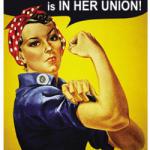

Trade Union Women

One of the joys of the 2010 British movie Made in Dagenham comes from watching a working-class woman who’s a trade unionist slowly discovering her ability to inspire other women to stand up to injustice and eventually lead them to victory. What adds to the fun is the fact that the story is based on real events — a strike in 1968 by sewing machinists working for the Ford Motor Company at the River Pant in the United Kingdom that led to the UK’s passage of the Equal Pay Act in 1970.

A book launch in mid-March for Gender and Leadership in Unions, a scholarly comparative look at women in the U.K. and the U.S.A., brought this film to mind and set off an exploration for their story and those of other factory women who took part in the fight against sex discrimination and for equality and power within their unions.

The stories of the fight for equal pay with men and the role of trade unionists and their allies in that struggle have receded in peoples’ consciousness. Most women in both the UK and the USA know little about either the leaders or the foot soldiers who took part in these epic battles for the 1970 Equal Pay Act in the UK and the Equal Pay Act of 1963 in the U.S.

Sarah Boston’s Women Workers and the Trade Unions, published in Great Britain in 1980, documents the history of women from 1874 to 1975. It’s a lively account, lucidly written, with chapter titles such as Asking for Bread and Getting a Stone (1923-39) and Be True to Us on Budget Day (1950-60). The last two chapters, Little Indication of Progress (1960-68) and You’ll Have to Do It Yourselves (1968-75) provide a vivid depiction of the possibilities brought about by women trade unionists of the Dagenham generation.

As Boston writes, “The early 1960s were curious years for women workers. They were transitory years between the conservatism of the 1950s and the new militancy of which the strike of machinists at Fords, Dagenham, in 1968 marked the beginning.” One important factor in laying the groundwork for militant dissent was the huge gap between women’s rights in the public sector versus those of the private sector:.

“Sick pay and occupational pension schemes, maternity leave and greater job opportunities were all gains which public sector women benefited from but were notably absent for women in private industry.”

Another factor was the huge increase in the number of female members in trade unions affiliated to the Trade Union Congress as women accounted for a full 70 percent of the increase between 1964 and 1970. As their numbers grew, women began to assert themselves within the trade union movement.

The summer of 1968 was a critically important milestone on a global basis — and a turning point for women workers. As Boston writes,

“In global terms the action of women at Ford’s may have seemed quite insignificant, but in terms of the long struggle by women workers in Britain for equality it was highly significant. The fact that it was a strike of women in a very clearly defined area of ‘women’s work—machinists demanding that the value of their work be recognized—was important. Equally important, the women demonstrated their industrial strength by bringing Ford’s Dagenham to a standstill. Although the strike was made official, it was very clearly a strike by women and for women, with very clear leadership from a well-organized, active women’s strike committee. Whilst it was not unique for women to demand recognition of their worth or to bring work to a halt, the bringing of the mighty Ford’s to a standstill by women machinists and the bringing in of Barbara Castle, the employment minister, to help negotiate a settlement attracted widespread attention to the strike. But it was the attention the strike drew from other women workers’ which was to give it its particular significance. Women had been growing impatient with the failure of the TUC and their unions to act in their interests and the strike at Ford gave women a lead. Other women quickly realized that if they wanted to improve their lot they would have to do so themselves and persuade, drag, or demand support from their fellow trade unionists. The strike marked a radical turning-point in the attitude of the women and men who formed the vanguard of the movement for women’s equal rights. Obviously this change did not happen overnight, but the Ford’s strike was the point from which the women’s movement in the British labour movement ‘took off’.”

For an analysis of the American counterpart to the British struggles documented by Sarah Boston, we look to Dorothy Sue Cobble’s The Other Women’s Movement: Workplace Justice and Social Rights in Modern America, published in 2004. Cobble’s book carries the story of working-class women’s activism or “labor feminism” forward from the 1940s through the comparable worth movement of the 1980s. Her analysis resurrects different variants of feminism and alternative visions of equality. This rich history explores the debate among trade union women over the fight for equal pay versus the broader, more expansive vision of comparable pay. She exhumes many previously unexplored corners and layers of female leadership in unions and allied organizations, and succeeds in documenting a vibrant socially and ethnically diverse movement for change.

From these two propitious thresholds, filled with possibilities and portents for progress, we move forward to the current assessment of women’s position in trade unions as documented by the research that went into Gender and Leadership in Unions. This is a collaborative product of British scholars Gill Kirton and Geraldine Healy, as editors and primary authors, and other academic researchers who made contributions to the project. In addition to the trade union women who took part in the study, ten U.K. women and ten U.S. women traveled to exchange insights and experiences, and in the process, established bonds.

The book is expensive ($125 from Routledge Publishing), is filled with citations that connect to the scholarly research and is written in clear, albeit academic language. But its utility is found in the baseline it provides for measuring the position of women and the issues they face in exerting their presence within their respective trade union movements.

The other quite useful function of the book is that it places the current research alongside earlier research and together creates an overall, in-depth picture of the subject.

The good news is minimal. We learn what any active trade unionist on either side of the Atlantic knows, but with documentation and context, that women are still in the position of having to push an agenda that prioritizes female workers’ needs and concerns — what the authors refer to as “gendered policies.” As they write: “istorically the unions have done little to challenge the prevailing pattern of gender segregation so strongly connected to gender inequalities, and some even argue that unions have even contributed to it by their efforts to exclude women from the best jobs and maintain women’s lower pay.”

Even with good reasons for changing the practices and behavior of male-dominated unions, resistance persists: “The structure of women’s employment and the impact of family on women’s employment participation make it clear that there is a distinct set of work issues that are of particular concern to women that the unions can no longer afford to ignore.”

The authors make the case for why it makes sense for unions to pay attention to gender-based issues:

There is a compelling argument on social justice grounds for unions to bargain and campaign vigorously at a variety of levels for improvements on behalf of women…The feminization of the labour market in recent decades means that there is also a business case for unions to develop and sustain gendered policies of attraction and retention.”

However, as they note, the timing for this agenda is bad: “It is obviously problematic that the debate about unions and gender equality is now taking place in the context of a weakened union movement.”

Whatever happened to the push in the late 70s and early 80s for gender equality and shared power? Why are women still peddling over the same ground? The chapter on Women Union Leaders: Influences, Routes, Barriers… offers plenty of insights. Subjects speak about exclusionary experiences and the litany of these behaviors is long and familiar:

Well it’s difficult just to be noticed … for us to say look we are here…The barriers are that union officials either feel threatened or just don’t buy into the equality issue…cannot deal with strong women and that’s a real problem.

Another familiar problem is the intersection of gender with race, “creating a hierarchy that distributes most leadership positions to white men, but that also privileges white women above women of color and other minority groups.”

Despite the recurring barriers women must cope with, changes are evident—and the situation isn’t unrelentingly depressing.

Some interviewees felt respected and supported by their male peers, with some stating that they did not feel marginalized at all in their unions. A significant number of respondents found that they gained respect once their male colleagues saw how competent they were. Some of these respondents stated they did not experience sexism in their unions, whilst others felt that their positive personal experiences co-existed with continued sexism in their union.

While women in both the US and the UK are underrepresented at the top of the unions and in their respective federations, the AFL-CIO and the TUC, some women – “notable exceptions” – despite all odds, have succeeded in gaining top positions.

An interesting question is, what, if any role does political consciousness play in the lives of active trade union women leaders? Here, unsurprisingly, researchers found a sharp divergence between women in the UK and the US when it comes to the influence of explicit political ideology on their commitment to the union and their view of leadership. Most of the UK high-level women leaders we interviewed made links between the labour movement, the women’s movement, class consciousness, and progressive politics…in describing the labour movement, one UK woman leader stated, ‘ tradition of internationalism is in our blood.

In contrast, “lthough the US high-level women leaders expressed deep commitment to the labour movement, they tended to identify their leadership philosophy as rooted in their personal ethics and involving a pursuit of individual fairness rather than related to larger issues of systematic injustice or power differentials.”

Now that the trade unions are almost flat on their backs and young people are sidelined as the shrinkage in labors’ ranks marginalizes union membership, organizing at the workplace is coming back into vogue. As this piece is written, thousands of fast food workers are walking off their jobs, mounting one-day strikes to call attention to their poverty wages and lack of benefits. For employees of Walmart and other low-wage empires that pay their workers next to nothing and make their survival dependent upon government assistance programs, organizing collectively alongside a union becomes an option for America’s new army of the underemployed.

Walking with eyes wide open into the ranks of labor is a necessity. An informed approach is critical. Learning about the history, the limitations and the possibilities of a revitalized labor—or labour—movement becomes part of the tool kit for workers crafting novel approaches to challenge their working conditions. Knowledge is a form of power.

For young women trying to fathom their role in creating a path to empowerment, a trip to the British blog Lipstick Socialist (http://lipsticksocialist.wordpress.com/) is highly recommended. It will provide an infusion of energy—a look at the traditions and the joy and power of collective action. The site, out of Manchester, links the trade union, feminist, and socialist traditions of Northwest Britain, and makes manifest what it means to be backed up by a conscious connection to the power of history.

Jane LaTour is a New York City labor activist and journalist. She is the author of Sisters in the Brotherhoods: Working Women Organizing for Equality in New York City and is working on an oral history about union dissidents and the limits of reform in organized labor.