High Quality Child Care Is Out of Reach for Working Families

Introduction and key findings

In recent decades most Americans have endured stagnant hourly pay, despite significant economy-wide income growth (Bivens and Mishel 2015). In essence, only a fraction of overall economic growth is trickling down to typical households. There is no silver bullet for ensuring ordinary Americans share in the country’s prosperity; instead, it will take a range of policies. Some should give workers more leverage in the labor market, and some should expand social insurance and public investments to boost incomes. An obvious example of the latter is helping American families cope with the high cost of child care.

The high cost of child care has received attention from an array of policymakers. For example, in his 2015 State of the Union address, President Obama cited child care affordability as a key to helping middle-class families feel more secure in a world of constant change (White House 2015). New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio recognized similar concerns and released an interagency implementation plan for free, high-quality, full-day universal prekindergarten (NYC 2014). High quality, dependable, and affordable child care for children of all ages is more important than ever, especially since having both parents in the workforce is an economic necessity for many families.

This paper uses a number of benchmarks to gauge the affordability of child care across the country. It begins by explaining how child care costs fit into EPI’s basic family budget thresholds, which measure the income families need in order to attain a modest yet adequate standard of living in 618 communities. The report then compares child care costs to state minimum wages and public college tuition. Finally, to determine how child care costs differ by location and family composition, the paper reconstructs budgets for two-parent, two-child families in 10 locations to include the higher cost of infant care, compares these families’ child care costs to those of families without infants, and compares costs for both family types with metro area median incomes.

Key findings include:

-

Child care costs account for a significant portion of family budgets.

- EPI’s basic family budget threshold for a two-parent, two-child family ranges from $49,114 (Morristown, Tennessee) to $106,493 (Washington, D.C.). In the median family budget area for this family type (Des Moines, Iowa), a two-parent, two-child family needs $63,741 to attain a modest yet adequate standard of living.

- Across regions and family types, child care costs account for the greatest variability in family budgets. Monthly child care costs for a household with one child (a 4-year-old) range from $344 in rural South Carolina to $1,472 in Washington, D.C.

- As a share of total family budgets, center-based child care for single-parent families with two children (ages 4 and 8) ranges from 11.7 percent in New Orleans to 33.7 percent in Buffalo, New York.

- Among families with two children (a 4-year-old and an 8-year-old), child care costs exceed rent in 500 out of 618 family budget areas. For two-child families, child care costs range from about half as much as rent in San Francisco to nearly three times rent in Binghamton, New York.

-

Child care is particularly unaffordable for minimum-wage workers.

- The high cost of child care means that a full-time, full-year minimum-wage worker with one child falls far below the family budget threshold in all 618 family budget areas—even after adjusting for higher state and city minimum wages.

- Among families with young children, child care costs constitute a large share of annual earnings for families living off one full-time, full-year minimum-wage income. For example, to meet the demands of infant care costs for a year, a minimum-wage worker in Hawaii—the state with the median state minimum wage ($7.75)—would have to devote his or her entire earnings from working full time (40 hours a week) from January until September.

-

Other salient benchmarks highlight the extremely high costs of child care.

- In 33 states and the District of Columbia, infant care costs exceed the average cost of in-state college tuition at public 4-year institutions.

- In terms of child care costs’ share of total family budgets, only in a handful of EPI’s 618 family budget areas are child care costs close to the 10 percent affordability threshold established by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

- Child care costs are particularly high for younger children. When 10 family budgets in various areas are reconstructed to include two-parent, two-child families with an infant and a 4-year-old (instead of a 4-year-old and an 8-year-old), child care ranges from 19.3 percent to 28.7 percent of total family budgets. This compares with a range of 11.8 percent to 21.6 percent for families with a 4-year-old and an 8-year-old.

- In these 10 areas, child care costs for an infant and a 4-year-old constitute between approximately 20 percent and 31 percent of median family income—far above the HHS’s 10 percent affordability standard.

Child care costs and EPI’s basic family budgets

Perhaps the best way to evaluate the affordability of child care is to determine the share of a family’s budget accounted for by child care costs. Toward this end, this paper relies upon EPI’s Family Budget Calculator (Gould, Cooke, and Kimball 2015), which measures the income families need in order to attain a modest yet adequate living standard where they live by estimating community-specific costs of housing, food, child care, transportation, health care, other necessities, and taxes, for 10 family types living in 618 U.S. communities.

Background on EPI’s basic family budgets

EPI’s basic family budgets differ by location, since certain costs, such as housing, vary significantly depending on where one resides. Geographical cost-of-living differences are built into the budget calculations by incorporating regional, state, or local variations in prices (depending on item). Basic family budget measurements are also adjustable by family type because expenses vary considerably depending on the number of children in a family (if any), and whether a family is headed by a single parent or two parents. The 10 family types include one or two adults with zero to four children. To estimate family costs, we assume one-child families have a 4-year-old, and that a second child is 8 years old, a third 12 years old, and a fourth 16 years old. (For more on the methodology used to construct the budgets, see Gould et al. 2015.)

The shares of expenses going to various categories vary substantially across areas and family types. Unsurprisingly, the lowest family budgets are for a single person. Except for child care (in which case families composed of two adults with no children also spend nothing), one-person families have the lowest expenses in every category. For example, they require only efficiency housing and only need to purchase other items, such as food and health care, for one. Budgets rise significantly with family size, since more children require more housing, food, health care, and child care.

What it takes to get by varies greatly across the country, as displayed in Figure A. For a two-parent, two-child family, the family budget threshold ranges from $49,114 (in Morristown, Tennessee) to $106,493 (in Washington, D.C.). In the median family budget area for this family type—Des Moines, Iowa—a two-parent, two-child family needs $63,741 to attain a modest yet adequate standard of living.

Annual income necessary to secure a modest yet adequate standard of living for a two-parent, two-child family, 2014

The cost of living in the Chicago/Joliet/Naperville, IL metro area is:

How child care costs fit into EPI’s basic family budgets

Child care costs are one of the most significant expenses in a family’s budget, largely because child care and early education is a labor-intensive industry, requiring a low student-to-teacher ratio (CCAA 2014). Across regions and family types, child care costs account for the greatest variability in family budgets. Monthly child care costs for a household with one child (a 4-year-old) range from $344 in rural South Carolina to $1,472 in Washington, D.C.

In EPI’s family budgets, child care costs in metropolitan areas—which constitute over 90 percent of our family budget areas—are statewide averages of the cost of center-based care. (For rural areas, which may not have easy access to center-based care, the budgets assume family-based care.) Although center-based care varies in quality, it serves as the standard for child care costs in the vast majority of our budget areas because it is the predominant form of child care (CCAA 2014).

However, center-based care is out of reach for many working families. Costs are particularly high for families with infants due to increased staff sizes and additional training and licensing requirements (CCAA 2014); center-based infant care costs range from $468 a month in Mississippi to $1,868 a month in the District of Columbia. Child care costs are even higher for families with multiple children; in the District of Columbia, monthly child care costs for a three-child household (with a 4-year-old, an 8-year-old, and a 12-year-old) are $2,784—nearly 90 percent higher than for a household with one child (a 4-year-old).

As a share of total family budgets, center-based child care for single-parent families with two children (ages 4 and 8) ranges from 11.7 percent in New Orleans to 33.7 percent in Buffalo, New York. When comparing child care costs with other budget components, the high expense of child care becomes even more evident. In fact, among one-child families with a 4-year-old, child care expenses exceed housing expenses in 90 of 618 family budget areas. Among two-child families with a 4-year-old and an 8-year-old, child care costs exceed rent in 500 of 618 family budget areas. For two-child families, child care costs range from about half as much as housing costs in San Francisco to nearly three times housing costs in Binghamton, New York.

Affording child care on the minimum wage

Affording child care is particularly difficult for families living off a minimum-wage income. By a wide range of measures, the current federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour is well below the historical peak reached in 1968, with profound implications for the standard of living of workers at or near the minimum wage (Cooper, Schmitt, and Mishel 2015). Even in the best of economic times, many parents in low-wage jobs will not earn enough through work to meet basic family needs. Indeed, annual wages total just $15,080 for a full-time, full-year worker (i.e., one who works 40 hours per week, 52 weeks per year) paid the federal minimum wage. Even after adjusting for higher state and city minimum wages, a full-time, full-year minimum-wage worker is paid less than is necessary for one adult to meet his local family budget threshold—and far below what is required for an adult with even just one child to make ends meet anywhere.

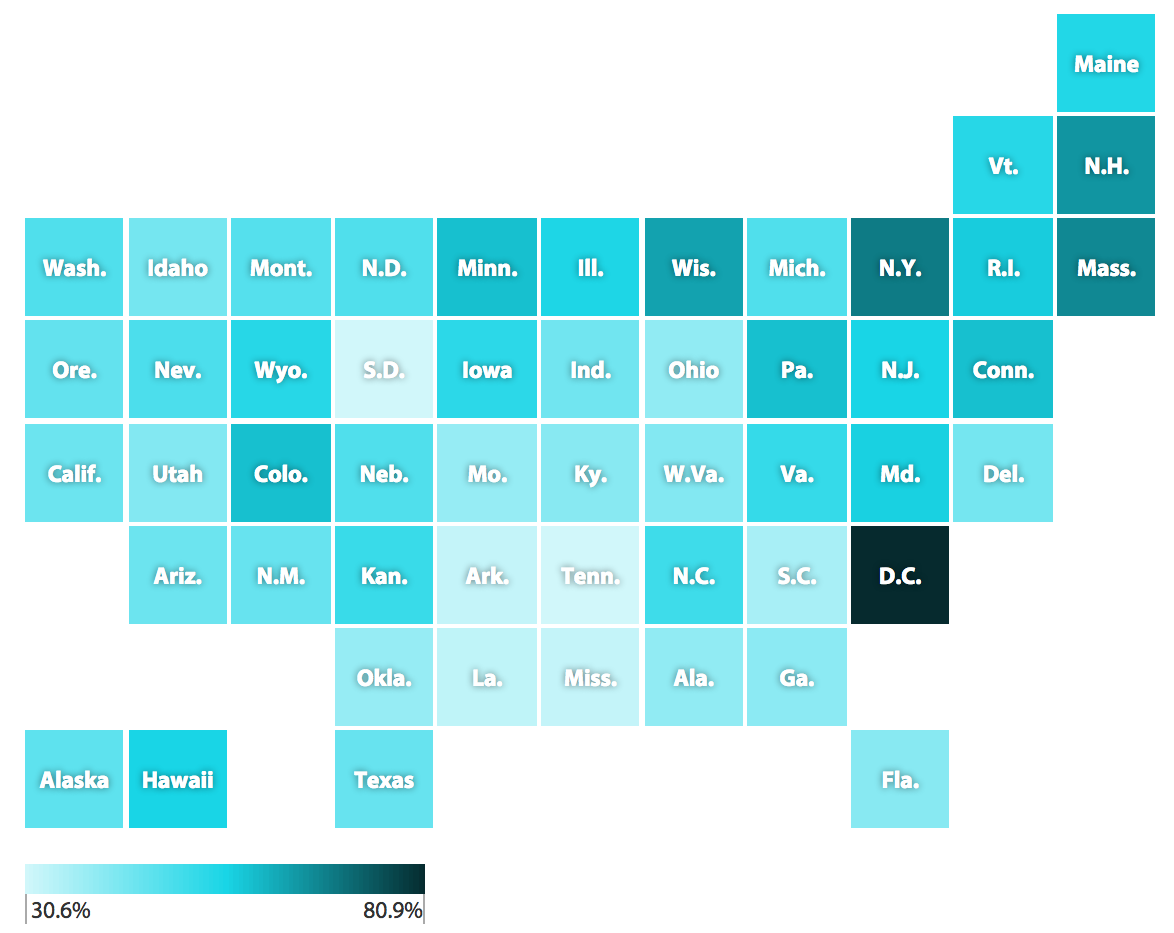

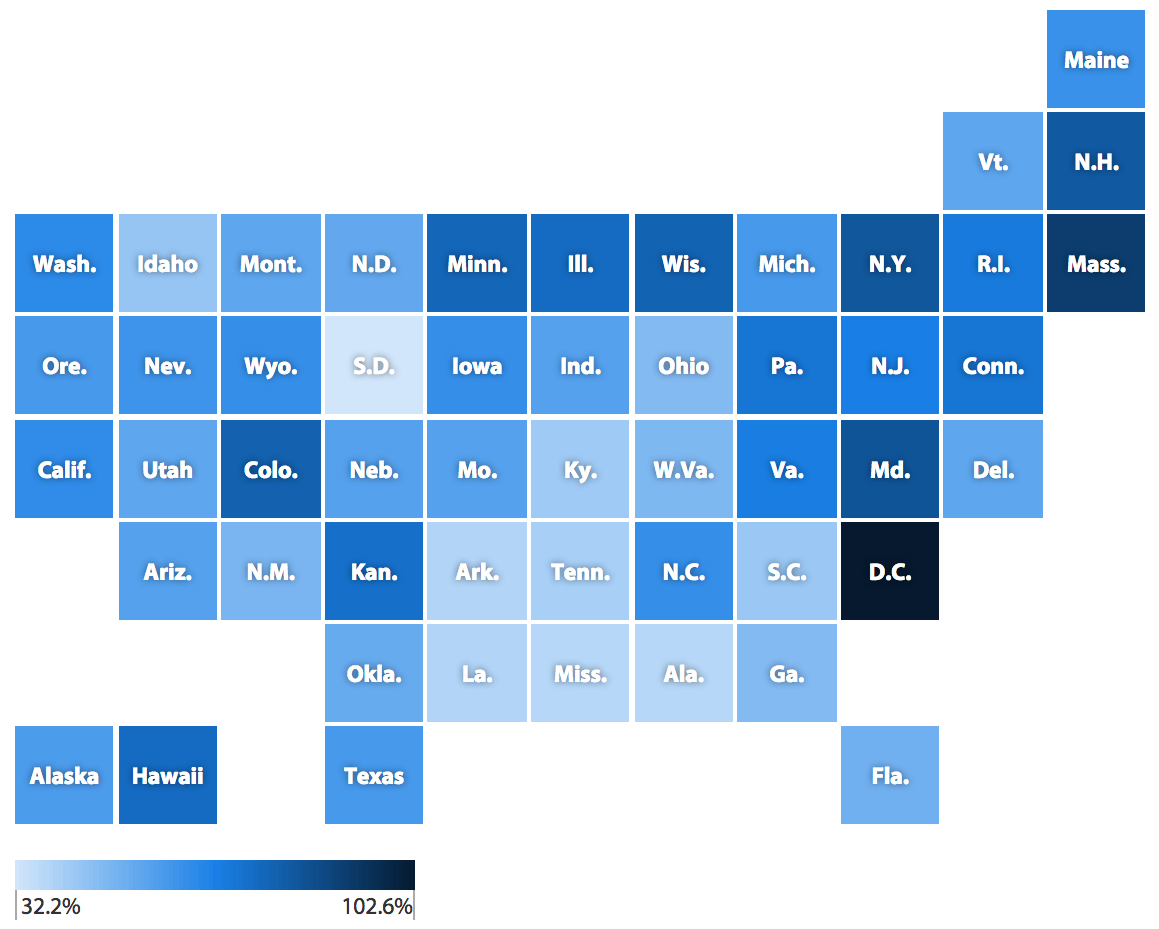

In fact, a large share of annual earnings from a full-time, full-year minimum-wage job must be devoted to child care. The shares of annual minimum-wage earnings required to afford 4-year-old care costs in each state are depicted in Figure B; Figure C depicts these shares for infant care costs.

Annual child care costs for a 4-year-old as a share of full-time, full-year minimum-wage earnings, by state

Annual infant care costs as a share of full-time, full-year minimum-wage earnings, by state

In Hawaii, the state with the median state minimum wage ($7.75), annual costs for 4-year-old care are equal to 55.8 percent of minimum-wage earnings. This means a minimum-wage worker would have to work 1,162 hours—or full time (40 hours a week) from January until July—to cover annual child care costs for a 4-year-old. In comparison, annual infant care costs in Hawaii are equal to 74.4 percent of minimum-wage earnings. In other words, to pay for infant care for a year, a minimum-wage worker in the state would have to work 1,548 hours, or from January until September.

Of course, in families with more than one child, these expenses are even higher. In two-child families, with an infant and a 4-year-old, child care expenditures as a share of full-time, full-year minimum-wage earnings range from 62.9 percent in South Dakota to 183.5 percent in Washington, D.C. (not shown).

Child care costs exceed college tuition in many states

High and rising college tuition is a well-known phenomenon; while hourly wages have stagnated, college tuition has grown faster than both overall inflation and median incomes, making college increasingly unaffordable (Barrett 2015). What is less well known is how comparable college tuition is to child care costs.

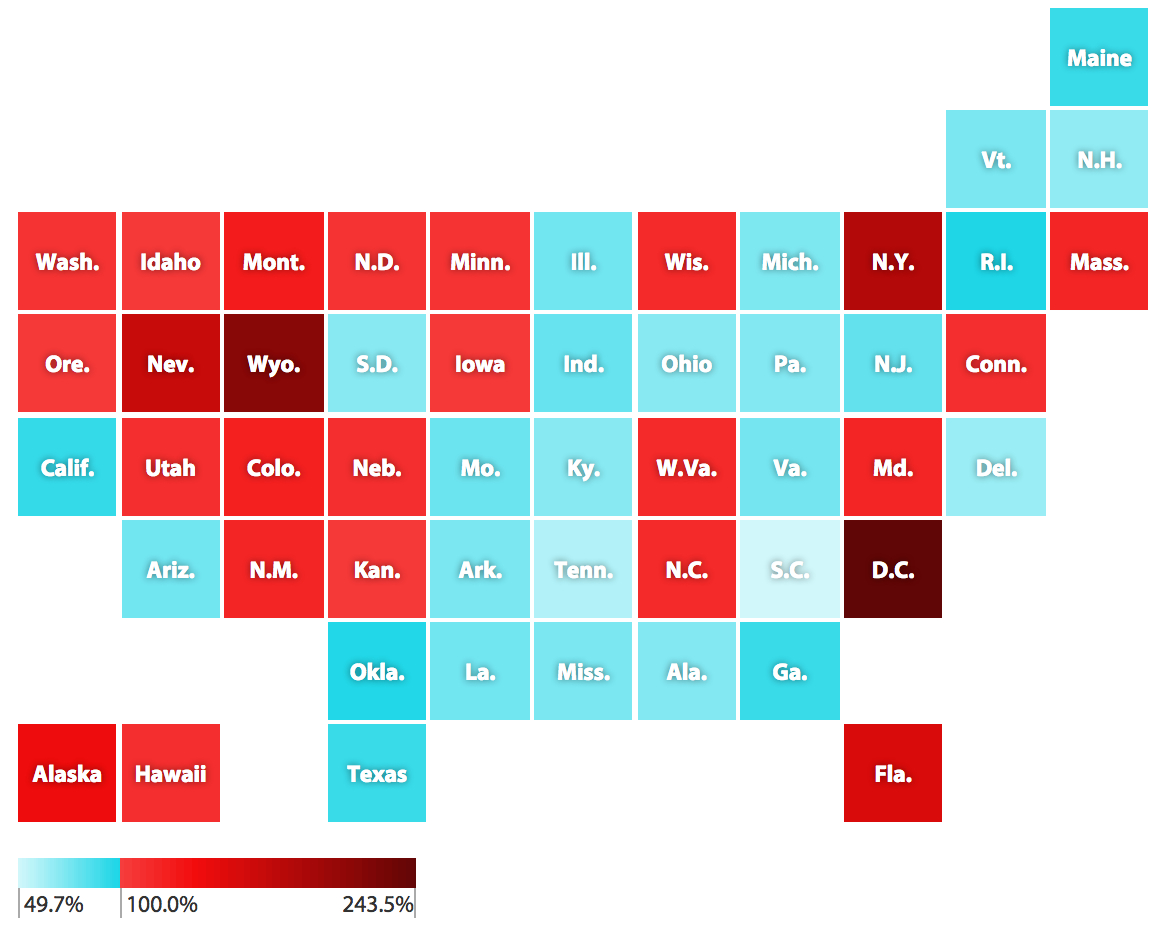

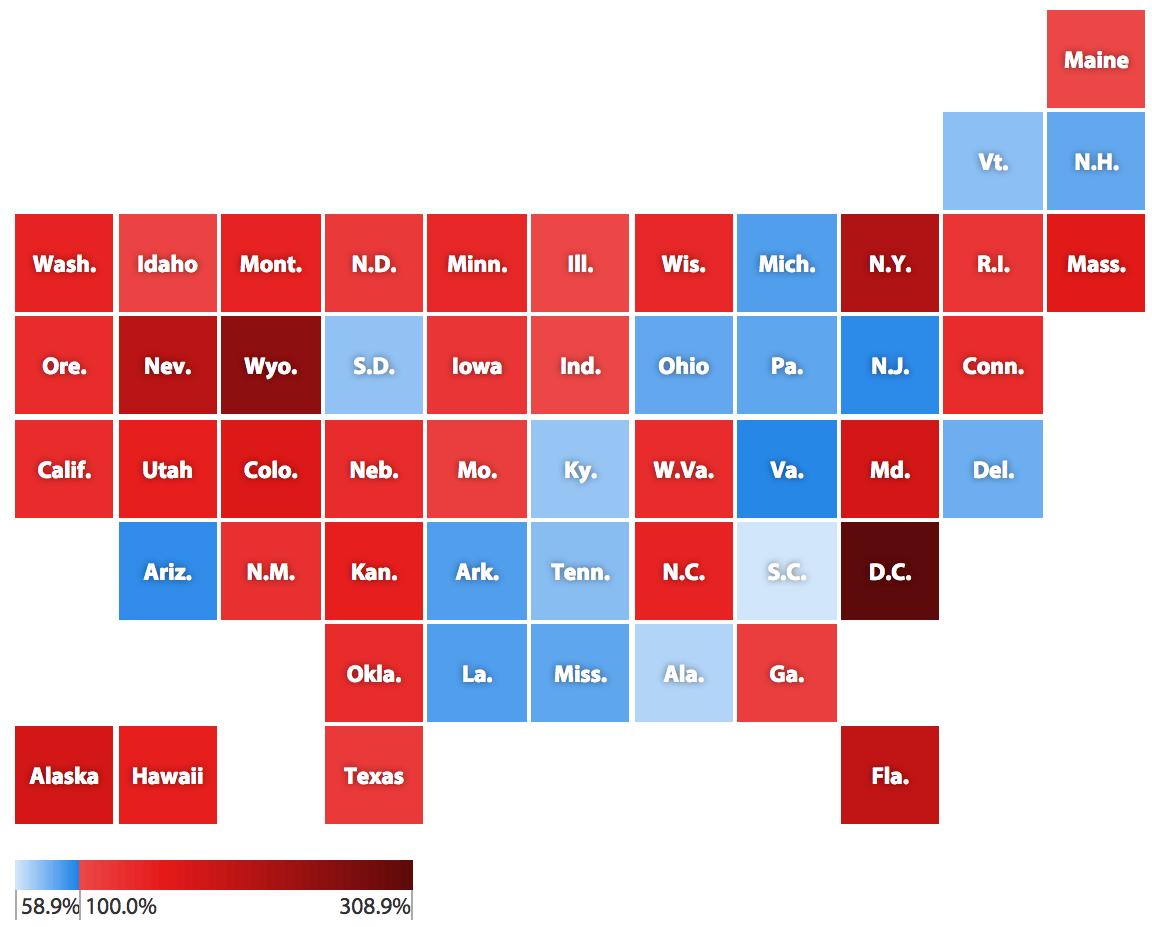

As with child care costs, postsecondary education costs vary greatly by institution type and state. The average annual cost of tuition for an in-state full-time undergraduate student in a degree-granting public institution ranges from $3,756 in Wyoming to $14,469 in New Hampshire (NCES 2014). While these sums are sizable, 4-year-old care exceeds the average cost of in-state college tuition at public 4-year institutions in 24 states and the District of Columbia (as shown in Figure D). Similarly, infant care costs exceed tuition in 33 states and the District of Columbia (as shown in Figure E). Even when looking at out-of-state tuition at public 4-year institutions, which is significantly more expensive than in-state tuition, college costs still do not dwarf child care costs.

Four-year-old child care costs as a share of full-time, in-state public college tuition, by state, 2014

Infant care costs as a share of full-time, in-state public college tuition, by state, 2014

Is child care affordable?

Another benchmark against which to measure child care costs is the Department of Health and Human Services’s official affordability threshold of 10 percent or less of a family’s income (HHS 2014). In only a handful of EPI’s 618 family budget areas (all in Louisiana) are child care costs close to 10 percent of the income required for a family with two parents and two children (a 4-year-old and an 8-year-old) to attain a modest yet adequate living standard.

As mentioned previously, child care is even less affordable for families with infants. To illustrate this, we reconstructed family budgets in 10 areas for two-parent, two-child families with an infant and a 4-year-old (instead of a 4-year-old and an 8-year-old). To account for population differences and geographic variations in the cost of individual components, we reconstructed budgets for a range of areas, including San Francisco; Stamford, Connecticut; Tampa, Florida; Atlanta; Chicago; Boston; Detroit; Kansas City, Missouri; Raleigh, North Carolina; and Las Vegas.

Costs greatly increase when substituting an infant for an 8-year-old in EPI’s basic family budgets, as shown in Figure F. While infants require a smaller food budget than 8-year-olds, infant care costs greatly exceed child care costs for an 8-year-old. Annual budgets for two-parent families with an infant and a 4-year-old range from $67,536 in Atlanta (which saw the smallest change in its overall budget, increasing $3,648) to $108,245 in Stamford. (Boston saw the largest change in its overall budget, increasing $16,921.) Annual child care costs for an infant and a 4-year-old range from $13,245 in Atlanta to $29,478 in Boston. As a share of total family budgets, these child care costs range from 19.3 percent in San Francisco to 28.7 percent in Boston. This compares with a range of 11.8 percent in San Francisco to 21.6 percent in Chicago for families with a 4-year-old and an 8-year-old.

Child care costs as a share of family budgets for two-parent, two-child families in select metro areas, by age of children, 2014

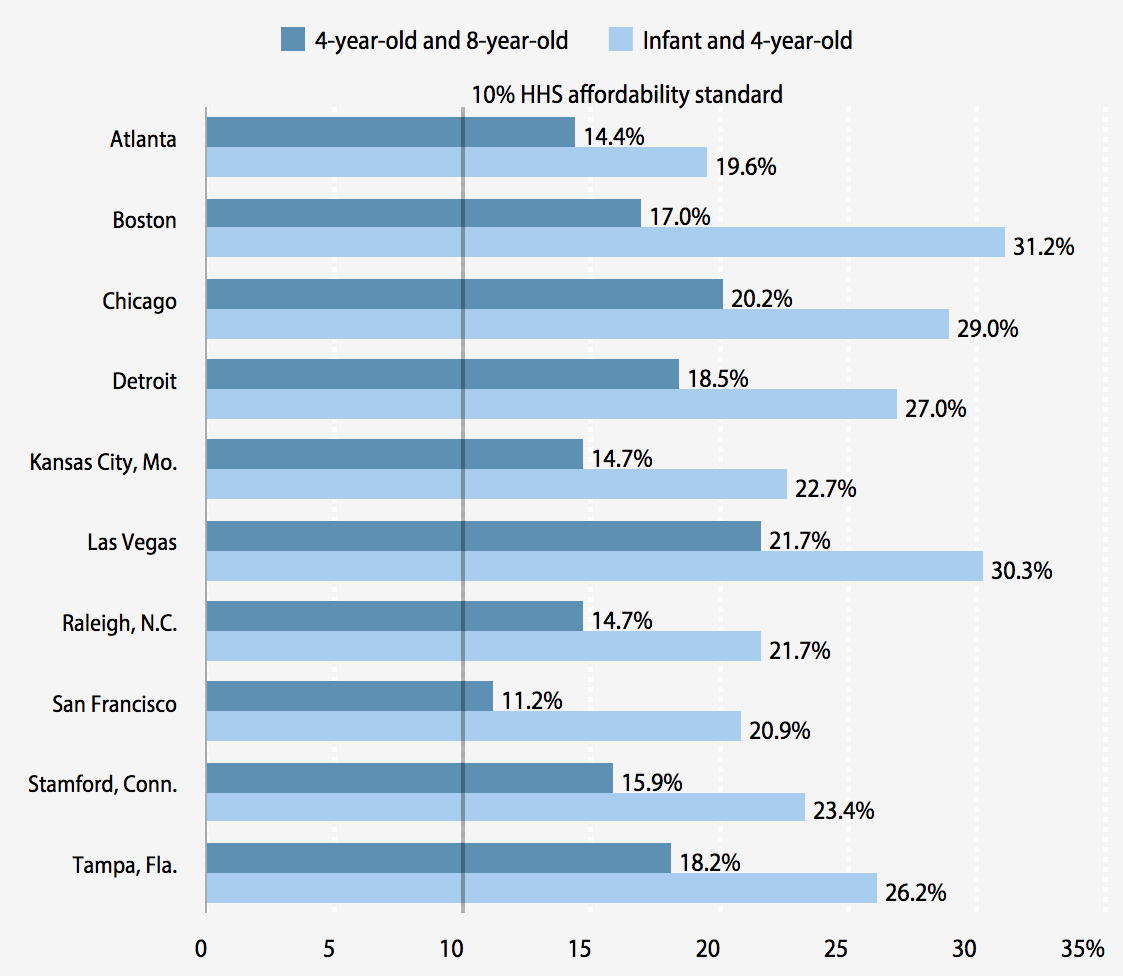

We next measure these child care costs against what families actually earn. Specifically, as shown in Figure G, we compare median incomes in these 10 areas to child care costs both for two-child families with an infant and a 4-year-old, and for families with a 4-year-old and an 8-year-old. Even in Atlanta—the area in our case study with the lowest child care costs—child care costs for an infant and a 4-year-old equal nearly 20 percent of median family income, almost double the HHS affordability standard. This share increases in places with more expensive child care, peaking in Boston at over 31 percent for an infant and a 4-year-old—over three times the affordability standard. However, lower child care costs do not necessarily equal affordability. For example, in Las Vegas—which had middle-of-the-pack child care costs in our case study—child care costs for an infant and a 4-year-old equal 30.3 percent of median family income, because the area’s median income is relatively low. This provides further evidence that child care is unaffordable for many families. Moreover, half of families actually earn less than the median, suggesting that far more families cannot afford child care than the data imply.

Child care costs as a share of median family income in select metro areas, by age of children, 2014

Conclusion

As policymakers look for ways to improve living standards for the vast majority of Americans who have endured decades of stagnant wages, increasing child care affordability is an excellent place to start. Child care costs constitute a large portion of the income families need in order to achieve a modest yet adequate standard of living—and are particularly onerous for workers paid the minimum wage. Measuring child care costs against a variety of benchmarks—including the cost of college tuition, the HHS’s 10 percent affordability threshold, and median family incomes—demonstrates that high quality child care is out of reach for working families.

Every week in the United States, nearly 11 million children younger than age 5 are in some type of child care arrangement. On average, these children spend 36 hours a week in child care, with costs ranging upwards of $500 a month for an infant (CCAA 2014). As child care consumes a larger proportion of family budgets, funding high-quality child care services should be a paramount concern for governments, business leaders, and families alike.

About the authors

Elise Gould, senior economist, joined EPI in 2003 and is the institute’s director of health policy research. Her research areas include wages, poverty, economic mobility, and health care. She is a co-author of The State of Working America, 12th Edition. In the past, she has authored a chapter on health in The State of Working America 2008/09; co-authored a book on health insurance coverage in retirement; published in venues such as The Chronicle of Higher Education, Challenge Magazine, and Tax Notes; and written for academic journals including Health Economics, Health Affairs, Journal of Aging and Social Policy, Risk Management & Insurance Review, Environmental Health Perspectives, and International Journal of Health Services. She holds a master’s in public affairs from the University of Texas at Austin and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Tanyell Cooke joined EPI in 2014. As a research assistant, she supports the research of EPI’s economists on topics such as wages, labor markets, inequality, education, race and ethnicity, and immigration. She holds a B.A. in economics and statistics from The George Washington University.

References

Barrett, Jennifer. 2015. “What’s the Value of a College Education? It Depends.” CNBC.com, June 19.

Bivens, Josh, and Lawrence Mishel. 2015. Understanding the Historic Divergence Between Productivity and a Typical Worker’s Pay: Why It Matters and Why It’s Real. Economic Policy Institute, Briefing Paper No. 406.

Bivens, Josh, Elise Gould, Lawrence Mishel, and Heidi Shierholz. 2014. Raising America’s Pay: Why It’s Our Central Economic Policy Challenge. Economic Policy Institute, Briefing Paper No. 378.

Child Care Aware of America (CCAA). 2014. Parents and the High Cost of Child Care: 2014 Report.

Cooper, David, John Schmitt, and Lawrence Mishel. 2015. We Can Afford a $12.00 Federal Minimum Wage in 2020. Economic Policy Institute, Briefing Paper No. 398.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2015. “Minimum Wage Tracker” (last updated September 15).

Gould, Elise, Tanyell Cooke, and Will Kimball. 2015. “Family Budget Calculator.” Economic Policy Institute.

Gould, Elise, Tanyell Cooke, Alyssa Davis, and Will Kimball. 2015. Economic Policy Institute 2015 Family Budget Calculator: Technical Documentation. Economic Policy Institute, Working Paper No. 299.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). 2014. Digest of Education Statistics, “Table B330.20: Average Undergraduate Tuition and Fees and Room and Board Rates Charged for Full-Time Students in Degree-Granting Postsecondary Institutions, by Control and Level of Institutions and State of Jurisdiction: 2012–13 and 2013–14.”

Office of the Mayor of New York City (NYC). 2014. “City Releases Implementation Plan for Free, High Quality, Full-Day Universal Pre-Kindergarten,” January 27.

Office of the White House Press Secretary (White House). 2015. “State of the Union Address.” January 20.

U.S. Census Bureau, various years. American Community Survey (2009-2013), “Table B19113: Median Family Income in the Past 12 Months (In 2013 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars).”

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 2014. “Fun”damentals of CCDF Administration.