Fifty years ago, the US Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling banning poll taxes in all elections. The case was brought by Virginia voters who challenged the Jim Crow-era law as a violation of their constitutional rights. Catherine Komp has more for Virginia Currents.

Learn More: Read the US Supreme Court's decision in Harper v Virginia Board of Elections. Find audio and complete transcripts of the Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections at the Oyez Project, an excellent resource for the US Supreme Court. Thanks to Commonwealth Recording in Omaha, Nebraska for their assistance and to the families of Ms. Butts and Mr. Jordan for providing archival photos and documents.

Transcript:

A faded pink pamphlet from the late 1950s outlines all the steps necessary to qualify to vote. First, pay three years of poll taxes, plus any penalties and interest. That sum was $4.50, the equivalent of $37.00 today. Charlene Ligon remembers her mother talking about barriers like these.

Charlene Ligon: There was a time in Virginia that when you went to register to vote, they give you a blank piece of paper and you had to guess what you need to put on the registration form.

On that blank piece of paper, you needed to answer from memory about a dozen questions, including your occupation for the last two years and the state, county and precinct where you voted in past elections.

Voter guide from Virginia's Third Force

Rodney Jordan: There were all kinds of devices used to try to deny African Americans and poor whites, we kind of forget that, basically poor people, from having the opportunity to vote.

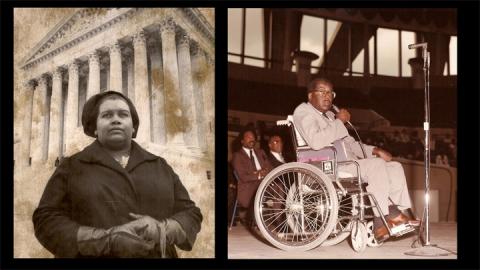

That’s Rodney Jordan. His uncle Joseph A. Jordan teamed up with Charlene Ligon’s mother, Evelyn T. Butts. The Norfolk civil rights advocates fought segregation, discrimination and voter disenfranchisement.

Charlene Ligon: She had never been afraid to speak her mind and she wasn't afraid of any of the tensions that might have gone on during those times.

Evelyn Butts was an entrepreneur, says Ligon, working as a seamstress to take care of the family after her husband was severely wounded in World War II. She was also a fierce advocate for equal rights and a talented organizer.

Charlene Ligon: My mom was on a very strong activist. She began her interest in politics and in civic endeavours about 1954, after the passage of Brown vs. Board of Education.

Joseph Jordan was also a veteran, paralyzed from the waist down during World War II. He spent four years recovering at McGuire Veterans Hospital, finished undergrad studies at Virginia Union University, then went to Brooklyn Law School. His law firm Jordan, Dawley & Holt, fought civil rights cases across the South.

Veteran, lawyer, lawmaker and judge Joseph Jordan

Rodney Jordan: It’s kind of hard to appreciate in 2016 but literally there were attorneys who were driven out of the state, there were families who faced terrorism as a result of their activism. Uncle Joseph shared with me himself that had it not been for his veteran’s pension and the salary that my Aunt Pat had, his wife, he probably would have been driven out of the state as well.

Jordan and Butts knew the ballot box was a path toward greater equality, Through a group called Virginia’s Third Force, they helped thousands understand the poll tax and register to vote. Rodney Jordan says it was a way to comply with the law while simultaneously working to eliminate it.

Jordan: The idea of Virginia's Third Force was you had Republicans, you had Democrats, and then you have this large group of disenfranchised individuals who were not allowed to participate because of poll taxes and other devices, so he coined them as this Third Force.

Their grassroots campaign included a “voter mobile” that traveled the state and a lawsuit to open up Norfolk’s voter rolls. After they won, Butts went down to the registrar's office, copied the voter info written on index cards and used the data to prioritize registration efforts.

Ligon: They would not give them what we take for granted now, we could go get a voter file. Where at that particular time, during that era, they weren't making the voter files public so that's why they they did that because they wanted to know who the voters were so they could target the non-voters.

Jordan: In 2016, where we have all this data and everyone is using technology and talking about social media and the ability to target voters by their voting history and where they live and what their preferences are, Mrs. Butts was doing that on index cards and with pen and paper and with a force of ladies supported by men and that’s how they were able to get people registered and organize communities and mobilize people.

Evelyn T. Butts, entrepreneur, civil rights activist.

By late 1965, the poll tax had been eliminated in federal elections and the Voting Rights Act had expanded protections and prohibited discriminatory measures like literacy tests. But Virginia, Alabama, Mississippi and Texas still maintained a poll tax in state and local elections. Vermont did too, for town meetings, town elections and school district elections. During this time, Jordan and Butts challenged Virginia’s poll tax in court. Their suits were dismissed, but they didn’t give up. The case finally made it to the US Supreme Court, consolidated with a similar suit, Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections.

Ligon: My mom talks about that day, you know that's really a great day for her, to have been able to attend that session at the Supreme Court, to have met Thurgood Marshall and also to have met Robert Kennedy, who was Attorney General and was in the courtroom that day. She was really excited to have met all of those folks and of course she was excited to be a part of history.

Justice Earl Warren: Number 48, Annie E. Harper et al., Appellants, versus Virginia State Board of Elections et al., and Number 655, Evelyn Butts, Appellant, versus Albertis Harrison, Governor, et al.

Rodney Jordan, nephew of Joseph Jordan

On January 25 and 26th, 1966, the US Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case. The late Allison Brown Jr. represented Fairfax’s Annie E. Harper.

Allison Brown Jr: This Court in the case decided last term, Harman v. Forssenius commented on the well-known fact that the disenfranchisement of the poor is occasioned by the failure to pay the tax. The tax not only disenfranchises persons without any means but persons who are below the level of economic income where the question of paying a tax represents a choice between the necessities of life, food, clothing, shelter, medicine, and so forth.

Brown cited census numbers at the time, that 28% of all Virginia families had incomes below $3,000 a year. Justices Stewart and Clark asked for clarification.

Potter Stewart: For a family, isn't it?

Allison W. Brown, Jr.: That's for a family income, yes sir.

Tom C. Clark: Did you say 28?

Allison W. Brown, Jr.: 28% of all Virginia families, yes sir. And among white families, it's 22% who have incomes below $3,000.

Charlene Ligon, daughter of Evelyn T. Butts.

And among nonwhite families, said Brown, 54% had incomes below $3,000.

Earl Warren: Mr. Solicitor General.

Joining the appellants’ lawyers in arguing the case was Thurgood Marshall. This was fourteen years after he argued Brown v. Board of Education and a year before he’d be appointed to the High Court.

Thurgood Marshall: The United States appears in this case because of the grave importance that our government attaches to the whole problem and while the poll tax is today in full force only in four states, Virginia, Alabama, Mississippi and Texas; and secondly, by virtue of the Twenty-Fourth Amendment applies only to state elections, it remains a serious clog in the exercise of the franchise. What is more, the problem of the poll tax as a real value to voting has become more not less acute. And the reason is that with the removal of most of the restrictions by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, it's pretty clear that the poll tax is going to be the one weapon left remaining and then it will come into its full position, I assert.

Ligon: She was just proud to be there, you know the Supreme Court is a huge symbol for democracy so I am sure that she-- you know it meant that her voice was heard and African-American voices were heard.

Jordan: The level of tenacity and determination that they had and I think this sense of patriotism. We talk about patriotism in some ways, I don't think we talk about patriotism enough when it comes to ensuring that every citizen has the right to take full advantage of all that our country offers.

George D. Gibson: Now, whatever may be the practice in other states, it has been repeatedly found that in Virginia, the poll tax is in fact administered without any racial discrimination.

Arguing for the state in support of the poll tax was George D. Gibson.

Gibson: I believe, Mr. Justice Fortas, he did. Counsel below said at the hearing and I quote that the only issue was “an economic hardship.”

Justice Warren asked Gibson whether a person who paid the $1.50 poll tax, but was delinquent on thousands of dollars of other taxes could still vote. After some back and forth, Mr. Gibson concedes the Justice was correct.

Gibson: Your honor, it’s quite rare. But it is quite true that the payment of all taxes is not required as a conditions to voting in Virginia.

On the second day of arguments, Joseph A. Jordan addressed the bench. He called Gibson’s arguments a “corruption of the history that we know.” He emphasized that before the reinstatement of the poll tax at the 1902 constitutional convention, many blacks “held numerous state offices, including numerous seats in the governing body of Virginia, its general assembly.”

Ligon (2nd left, bottom row) and the Jordanettes.

Joseph A Jordan: Almost like a magic wand after the passage of this law, these poll tax laws, not a single Negro has sat in the Virginia General Assembly, and not a single Negro has held a single elected state office in the state of Virginia. We say that the evil intent was accomplished and that it was accomplished in direct confrontation to the Fifteenth Amendment. We say that there is discrimination in Virginia which deprives Negroes of the right to vote and we say this is a direct violation of the 15th Amendment.

The US Supreme Court delivered a decision in less than two months, ruling that a fee or tax in order to vote violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. In a Virginia Pilot article from March 25th, 1966, Evelyn Butts said she was sewing when she got the news. “I was very glad it was all over,” she told the paper. “It will help the state of Virginia to progress.” Joseph Jordan had a similar sentiment, saying “It has given my state the way to get into the 20th century.”

Ligon: That was a great day because they had won the case and it proved the point that the poll tax actually kept poor people and only poor black people but poor white people from voting so it kept a lot of people from participating in the process.

Jordan: The sense of pride, the sense of euphoria, the sense of being a full citizen. Even to this day I think we still find ourselves struggling at times to feel like we belong and so I just feel like the opportunity to participate in American democracy meant so much to them. That’s why you saw the voter registration swell and voter participation rates swell because they valued that vote and that franchise that has been denied for so long.

Jordan, after he was elected to City Council.

The end of the poll tax, combined with continued voter education efforts, led to some of the first African Americans elected to office since Reconstruction, including Joseph Jordan himself. He won a seat on Norfolk’s City Council in 1968 and later served Vice Mayor. In 1977, he appointed as a General District Court Judge.

Jordan: William P. Robinson came into the House of Delegates in 1970 I believe it was, Doug Wilder who was also someone who attended Virginia Union as Uncle Joseph did ended up in the Senate and later became governor. So the push of African Americans and women into elected office, I believe can be traced right back to the elimination of the poll tax.

Evelyn Butts continued her community and political organizing and became the first black female commissioner of Norfolk’s Redevelopment and Housing Authority, where she fought for families to have safe and affordable housing.

Ligon: One of the things she stressed when they started to redevelop Oakwood and Rosemont, that she did not want it to be a housing project, she wanted it to be a place where people could buy affordable housing. Home ownership was important to her, that people should own their homes instead of renting, so yeah that was really important to her.

Jordan: I think they were visionaries, their creativity was unmatched, I believe; just the ideas that they came up with, the fortitude that they had. For Mrs. Butts and Uncle Joseph, they put their livelihoods at at risk so to believe in a cause that much and to believe in justice to that extent, to really put your family and your personal well-being at stake, I just think speaks volumes. And if we can celebrate Patrick Henry and if we can celebrate Thomas Jefferson and if we can celebrate these others, I think we should celebrate all those who have worked towards trying to make sure that this American ideal is realized.

There are no monuments recognizing Butts, Jordan and others who fought to end Virginia’s poll tax. But in Norfolk, the late Joseph A. Jordan has a public library named after him, and Evelyn T. Butts, has an avenue.

Lignon: And what’s amazing is that it is the end of the line for a lot of bus routes so when you are in Norfolk and you see a city bus, it is not uncommon to see a bus with the name Evelyn T Butts Avenue on it so it does keep her name alive. And I've met some people and they say, I've been to Norfolk and I noticed that name of Evelyn T Butts Avenue and I wondered who was Evelyn T. Butts? So it's a great tribute to have had that done for her.

The legacy of Evelyn T. Butts also lives on through her daughter’s work. Now retired from the US Air Force and living in Nebraska, Charlene Ligon’s organized voter registration campaigns, is Chair of the Sarpy County democrats and this year, set up caucuses in 93 counties. She says if her mother were still alive today, she’d be in the streets too, getting out the vote. For Virginia Currents, this is Catherine Komp, WCVE News.

Spread the word