The Black Panther Party is often associated with armed resistance, but one of the most potent weapons in its outreach to African-Americans in cities across the country was its artwork. In posters, pamphlets and its popular newspaper, The Black Panther, the party’s imagery was guided by the vision of Emory Douglas, its minister of culture.

His art came from many sources. As a teenager in San Francisco during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Mr. Douglas found himself incarcerated at the Youth Training School in Ontario, Calif., where he got involved with its printing shop. He went on to study graphic design at San Francisco City College, where he developed a deep interest in the Black Arts Movement, the artistic arm of the Black Power Movement.

His particular background, a combination of art, printmaking and activism, eventually attracted the eye of the Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale, and led to Mr. Douglas’s becoming a central figure in the party. The newspaper’s circulation eventually climbed to over 200,000, making it one of the most popular black newspapers of its day. In the years since the party’s demise, Mr. Douglas’s posters have come to be known as iconic artifacts of their era.

Mr. Douglas’s work is currently on display in an exhibition at Manhattan’s Urban Justice Center, and it remains a touchstone for many younger artists looking to marry their practice and their social consciousness. The painter Jordan Casteel, 27, an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, called Mr. Douglas’s work “a literal depiction and a visual representation of a time.”

“Art serves as a blueprint to be inspired by, but it’s also a language that continues on,” she said.

To create a conversation between the past and present, and to explore the relevance and importance of his Black Panthers artwork 50 years later, we interviewed Mr. Douglas, who is now retired but still creating art, traveling, and living in San Francisco, along with two young artists who often look to him for inspiration: Ms. Casteel and Fahamu Pecou, whose solo exhibition, “Black Matter Lives,” is on view at the Lyons Wier Gallery in Chelsea. Their comments below have been lightly edited for space and clarity.

War and Protest

Emory Douglas: The reaction to my Vietnam War art then was positive. It was a message to the G.I.s and to the broader community that the abuses, murders and lynchings of people in our community was not caused by Vietnam or the Vietnamese. Our struggle was not in Vietnam, our fight was here in the United States. The tears in the image reflect the pain and suffering that I heard when I talked to people in the struggle, or in the military.

Jordan Casteel: This image of a black man crying challenges our perceptions of masculinity and strength in our community. It acknowledges black people fighting in a war but questioning, “What is our war? What battles should we be in? And how do we make those decisions? What war is ours? What does it mean to be in battle with your own country?” The evidence is there in the photos on the helmet: We are being killed in the streets here but also being asked to kill or be killed in another country. It is so jarring to me. It made me feel uncomfortable, but in all the right ways.

Fahamu Pecou: One of the major tenets of their agenda was to shape their own media image, as opposed to having their image be dominated by the more dominant media landscape. So coming up with the pamphlets and The Black Panther newspaper was all a part of that agenda: “If we wait for someone else to tell our story they’re going to paint a picture of us that doesn’t reflect our values, doesn’t reflect our agenda. So we have to lead the charge on what the Black Panther Party is about.” And that’s where these images really come from.

Powerful Women

Emory Douglas: My daughter’s mother worked with me designing for The Black Panther newspaper. There was also Tarika Lewis, who was the first artist that worked with me on the newspaper as an artist. And then there were many other women who contributed to the production of the newspaper. The women depicted in my artwork are a reflection of the party. Women went to jail and were in leadership roles. Women started chapters and branches of the Black Panther Party as well. When we used to read some of the stories, you would see women in the Vietnam and Palestine struggle and in the African liberation movement. Women were an integral part of those movements so all that played into how I expressed them in my own artwork.

Fahamu Pecou: In my own work, I am often working from a position of changing the perspective that we as black people have about what we can do with our bodies, and what kind of power we actually possess. So, trying to move ourselves from a perception of ourselves as being victimized and rather seeing ourselves as being empowered, and being capable of making the changes that we want to see. And I think that that takes a great deal of work, to change the way people see themselves. When we have various atrocities that happen within the black community and to the black community, and we continue to survive, we continue to thrive — it brings you a reflection of the power that’s deep within us. So I’m interested in that idea: that we can change the way we move in the world by changing the way we think about and see ourselves in this society.

Jordan Casteel: Emory was working toward getting people information through his visual language, and that necessity was much more pungent at that time. Now information can just be turned over immediately. You can take a photograph, upload it to Instagram or Facebook and say, “This happened.” Then all of a sudden on social media, we are all chiming in to a visual language and trying to take a stance. Using graphic design and graphic imagery as a way to take a stance behind something is still a part of my generation.

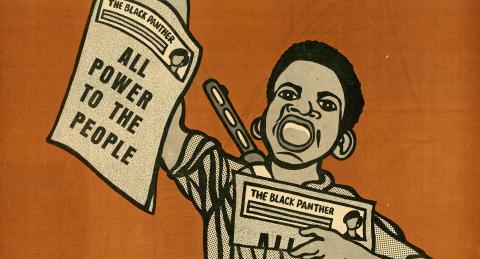

Panther Kids

Emory Douglas: Racial profiling was taking place back then and is taking place now, too. So, I wanted to express the police abuse in the community. The photograph on the right was actually taken when we would take our Panther kids to the courthouse where they would get patted down by the security there. I think this image also connects today in the context of Black Lives Matter and being more aware of the profiling that exists in this country. People can see how frustrating it is for those dealing with profiling and how that creates the conditions for resistance.

Jordan Casteel: Kids represent an innocence, and Tamir Rice is all I can think about looking at this. He was a young boy who was just playing, and his life was struck. I think of my nephews as well, because they are being raised at a time when what it means to be a young person of color is in question. But it’s important to still create possibility and dreams. They should be whatever they want to be and we have to create that world for them.

Fahamu Pecou: These images that feature children I think are really, really impactful. To be able to use their platform as a way to initiate children into a certain way of thinking about themselves in the world, or thinking about what the Black Panther Party was doing, I think was really a brilliant practice. The Black Panther Party’s work with children also helped them to have an inroad with the adults, because the adults saw that these people are really invested in the livelihood of this community. They’re not just out there starting trouble with the cops. They’re really doing something to help save the babies.

‘All Power to the People’

Emory Douglas: When Huey Newton and Bobby Seale would come to San Francisco for community organizing, they were often confronted by the police and so they began to call them swine and pigs. Out of their conversations about the police came the definition of a pig: a no-nation beast that has no regard for rights, the law or justice and bites the hand that feeds it. So one day, Huey and Bobby gave me this clip art of a pig on four legs that they wanted me to draw. In American culture, pigs are animals wallowing in filth and dirty. So I took that thought and applied it to the pig drawing itself. Then once I put the pig on two legs, gave it a badge and had the flies flying around, it transcended the boundaries of the African-American community and became an international icon that everybody identified with as a symbol of oppression by government and the police. In the context of today, if a pig image was used in a contemporary way, I’m pretty sure it would have the same kind of impact.

Fahamu Pecou: It was about being able to speak to people on multiple levels, so of course you had the language, the text, which was informative and spelled out very clearly what the Black Panther Party represented. But these images also worked to operate on a different intellectual, psychological register that would get into people’s minds and help them not just read about themselves or know themselves, but see themselves as empowered, see themselves as agents of change. See themselves as heroes, and see the villains as they were. And I think those kinds of things are really powerful. It really speaks to the power of the visual art, to operate as a kind of text itself.

Jordan Casteel: I think everything here is about hope. Even if the guns are present, revolution isn’t always about destruction. It’s about re-creation. It’s about resurrection. It’s about new beginnings.

Seeking Justice

Emory Douglas: Even though we may plot for progress, in many ways there is still structural racism and institutional racism that exists today and has to be dealt with. So that’s what I try to continue to do with the art itself is try to make a contribution to those issues. Fifty years later though, it makes me think that the struggle continues.

Jordan Casteel: What does it mean to be a person who literally feels hypervisible and invisible at the same time? Black and brown bodies are forced to deal with that every day. At some point you have to make choices about how you want to be projected in that state of being seen and unseen. As artists, we have the choice to contribute to that visual language and contribute a potential change to its understanding, fear, love or history. And Emory has done that. He participated in and contributed to that history.

My own work came about from noticing the differences between what I would see of those I loved, particularly black men like my brothers and father, and how they were portrayed by the world. The portrayals were full of fear or assumptions I never understood. So I used my paintings to enlighten and inform but also genuinely create a sense of empathy for these men — to really see them.

Fahamu Pecou: I think that sentiment of “revolution in our lifetime” is something that really resonates with today’s movement. There appears to be very little patience for change — we really want to see it. Too many of us have dealt with lip service for many, many years from our so-called political leaders, and others who have continued to try to talk us into waiting for change to happen, or to be patient with the process, or to allow justice to take its course. And as we’ve seen over several of these police shootings, and just different kinds of impositions like stop-and-frisk, this whole notion of justice taking its course is not going in the direction that we’re moving in.

New Era, Same Voice

Emory Douglas: Sometimes there are those in the community who feel strongly but may not be able to act in that way so you capture that in the artwork. The art is a language, communicating with the community. The sense of urgency shown comes from what we had seen and we’re doing. The fact was that we could be wiped off the map at any given time. The urgency in the artwork was a reflection of the urgency in the race and the fear that people had. You had to be accessible to the community and interpret them into the art like making the people heroes on the stage. There’s also a sense of urgency today, of course, it just comes out in a different way.

Jordan Casteel: An older woman and an older man talking about “Seize the Time” is pretty phenomenal, and telling. What does it mean to come out of slavery and to now seize one’s voice? It says, “I want to be seen, I want to be heard.” These guns are symbols of war and carnage, yes. But the carnage has already occurred for black people, and continues to occur.

Fahamu Pecou: Being an artist who plays with text in my work a lot, I’m certainly attracted to Douglas’s use of text. For me the things that really stand out are those phrases like “revolution in our lifetime,” or “seize the time.” The immediacy of those phrases in relation to the politics in the image is something that really resonates: what needs to happen, what we want to happen, has to happen — now, not later, not on someone else’s clock, but now. It’s because of the children. In all those images, you always see children. The pin that the brother’s wearing in front has a child on it. So the importance of this notion of revolution is underscored by a reflection of how it will impact our children. And I think that is really powerful.

Jordan Casteel: I talk about how I grew up in the time of Black Lives Matter and it was important just like my mom remembers her Afro and pinning a “Free Angela” sticker on her fridge. We are all talking about the same things. When we get to the core of that intergenerationally, all of us are still fighting for the same voice.

‘Clues of Hope’

Emory Douglas: This image was about hope. Every day we were around the community kids and the schools. These children were Panther cubs who grew up in the party, lived in collectives and went to the alternative school where the kids were taught how to think and not what to think so they could analyze for themselves and critique for themselves. So this spirit of growth, development and survival was what it was all about. And I wanted to reflect that spirit in the art. If young people can continue to get knowledge, they would survive.

Jordan Casteel: I felt this piece of work the most initially, because of that desire to share an example of something different, beautiful and transformative. I think we both desire, in the end, to transform a mind-set or a way of thinking that has been destructive to our communities.

Fahamu Pecou: The power of the visual is really what allows some of the messages of the party to really resonate with people. It was more than political rhetoric. It was underground action, in an effort to save, protect and raise our children to be strong, healthy, functioning adults.

Jordan Casteel: In this work in particular, it’s kind of amazing how Douglas designs the sun rays. They look like sun rays to me because of the circular pin of a young boy at the top of the hat; it is so reminiscent of a sun. These upward rays generate, to me, a beginning rather than an ending. It’s a sunrise. There are a lot of clues of hope. Emory kept the minimalism and the beauty of what he created. He made something out of nothing. That’s real. That’s lemonade. And that’s why we’re artists.

Spread the word