Identifying the Policy Levers Generating Wage Suppression and Wage Inequality

Inequalities abound in the U.S. economy, and a central driver in recent decades is the widening gap between the hourly compensation of a typical (median) worker and productivity—the income generated per hour of work. This growing divergence has been driven by two other widening gaps, that between the compensation received by the vast majority of workers and those at the top, and that between labor’s share of income and capital’s. This paper presents evidence that the divorce between the growth of median compensation and productivity, the inequality of compensation, and the erosion of labor’s share of income has been generated primarily through intentional policy decisions designed to suppress typical workers’ wage growth, the failure to improve and update existing policies, and the failure to thwart new corporate practices and structures aimed at wage suppression. Inequality will stop rising, and paychecks for typical workers will start rising robustly in line with productivity, only when we enforce labor standards and embrace policies that reestablish individual and collective bargaining power for workers.

Between 1979 and 2017, the compensation of median workers trailed economywide (net) productivity growth by roughly 43%, leading to rising inequality. The effects have been felt broadly: During this time 90% of U.S. workers experienced wage growth slower than the economywide average, while workers at the top (mostly highly credentialed professionals and corporate managers) and owners of capital reaped large rewards made possible only by this anemic wage growth for the bottom 90%. Because the historical legacy of racism has concentrated Black and Latinx workers in the lower half of the wage scale more so than white workers, widespread wage suppression based on class position has inflicted disproportionate harm on them. Further, while women’s wages have grown faster than those for men in recent decades, women’s wage growth still has lagged the economy’s potential. In the fight for a piece of the ever-shrinking share of economic growth available to the bottom 90%, any one group’s gain can feel like another’s loss, leading to political divisions and hindering the formation of cross-racial coalitions based on common interests as workers. In other words, the disappointing wage growth of recent decades is an important economic and political issue.

Yet sluggish wage growth is not a political secret; it has been widely recognized across the political spectrum, even cited by both the Republican and Democratic Party platforms in 2016.1 The root causes of the trend have frequently been misidentified, however. One prominent interpretation is that disappointing wage growth is an unfortunate result of apolitical market forces that one neither can nor would want to alter. Since labor markets are generally competitive and workers and employers have roughly balanced degrees of market power, this argument naively assumes, fundamental apolitical forces like technological change and automation, as well as globalization, have mechanically shifted demand away from non-college-educated and middle-wage workers. But, as this paper will show, the premier research cited in support of an automation/technological theory has itself actually offered empirical metrics that demonstrate that automation/technological change fails to explain wage trends and wage inequality, especially in the period since 1995. Since the automation/technological change explanation is the preeminent explanation drawn from competitive labor market analyses based on equal bargaining power between employers and employees, the failure of automation/technological change to explain wage suppression and wage inequality represents the inability of competitive labor market analyses to adequately explain one of the most salient features of the economy over the last four decades.

Thus, we need to look further for more convincing empirical explanations of why, during a period of rising productivity, hourly compensation for the bottom 90% of all workers has risen so slowly in spite of overall income growth. Doing so requires explaining the key dynamics. The growing wedge between rising productivity and compensation growth for the typical worker financed the increased share of compensation going to top earners, especially those in the top 1% and 0.1%, along with a declining share of income going to labor. In addition, over the last four decades there has been a persistent disparity in the growth of earnings between those in the 90–99% range and those in the middle. Further, wage disparities by gender, race, and ethnicity from the late 1970s, reflecting systemic sexism and racism, remain with us and have sometimes even worsened. Any accounting of where we are and what policies we need must address these issues.

This paper offers a narrative and supporting evidence on the mechanisms that have suppressed wage growth since the late 1970s. We refer in this analysis to wage suppression rather than wage stagnation because it was an actively sought outcome—engineered by policymakers who invited and enabled capital owners and business managers to assault the leverage and bargaining power of typical workers, with the inevitable result that those at the top claim a larger share of income. These policy changes and the change in business practices they enabled have systematically undercut individual workers’ market (exit and voice) options and the ability of workers to obtain higher pay, job security, and better-quality jobs. These corporate and policy decisions had the most adverse consequences for low- and middle-wage workers, who are disproportionately women and minorities, the groups whose legacy of being discriminated against in labor markets means that they especially need low unemployment, unions, strong labor standards, and policy supports for leverage when bargaining with employers.

Neither slow productivity growth nor inevitable economic forces can explain U.S. wage problems. Rather, wage suppression reflects the failure of economic growth to reach the vast majority. It was a “failure by design” (Bivens 2010), engineered by those with the most wealth and power. The dynamics are primarily located in the labor market and the strengthening of employers’ power relative to their rank-and-file workforce (which increasingly includes those workers with a four-year college degree). In other words, the dynamics that have challenged the growth of living standards for the vast majority are based on workers not sharing in economic gains, not, as some have argued, on consumers suffering from monopolistic prices. Changes in product market monopoly and corporate structures have had an impact, but primarily by squeezing supply chain profits and wages rather than by spurring higher consumer prices through much wider profit margins.

As we will discuss, six factors can collectively explain most of the growth of wage inequality and the erosion of labor’s share that resulted in wage suppression over the last four decades (specifically 1979–2017):

- Austerity macroeconomics, including facilitating unemployment higher than it needed to be to keep inflation in check, and responding to recessions with insufficient force;

- Corporate-driven globalization, resulting from policy choices, largely at the behest of multinational corporations, that undercut wages and job security of non-college-educated workers while protecting profits and the pay of business managers and professionals;

- Purposely eroded collective bargaining, resulting from judicial decisions, and policy choices that invited ever more aggressive anti-union business practices;

- Weaker labor standards, including a declining minimum wage, eroded overtime protections, nonenforcement against instances of “wage theft,” or discrimination based on gender, race, and/or ethnicity;

- New employer-imposed contract terms, such as agreements not to compete after leaving employment and to submit to forced private and individualized arbitration of grievances; and

- Shifts in corporate structures, resulting from fissuring (or domestic outsourcing), industry deregulation, privatization, buyer dominance affecting entire supply chains, and increases in the concentration of employers.

Concretely, our analysis attempts to account for the 43 percentage point divergence between the growth of productivity (net of depreciation) and median hourly compensation (wage and benefit) growth between 1979 and 2017. This 43 percentage point wedge excludes any impact of the differing measures of prices used to inflation-adjust productivity and compensation growth. Had median hourly compensation grown with net productivity it would have increased from $20.48 in 1979 to $33.10 in 2017 ($2019). In fact, median hourly compensation was $23.15 in 2017, a $9.95 shortfall from the net productivity benchmark.

We estimate that the first three factors—the impacts that are largest and best measured, i.e., excessive unemployment, eroded collective bargaining, and corporate-driven globalization—explain 55% of the divergence between growth in productivity and median hourly compensation, and specific other factors included above—a diminished overtime salary threshold, employee misclassification, employer-imposed noncompete agreements, and corporate fissuring-subcontracting and major-buyer dominance—explain another 20%. Together, the factors for which we have been able to assess their impact on the median wage can account for three-fourths of the divergence between productivity and median hourly compensation growth from 1979 to 2017. Other factors that we have not been able to empirically assess—increased wage theft and weak enforcement, anti-poaching agreements, increased discrimination, forced arbitration agreements, guestworker programs, and increased prevalence of employer-created “lawless zones” in the labor market where workers are deprived of effective labor protections because of their immigration status—have also contributed to wage suppression.

Our analysis also seeks to account for the falling wages at the 10th percentile and the growth of the wage gap between the 10th percentile and the 50th. We find that these are readily explained by excessive unemployment and the failure to maintain the real value of the minimum wage, factors that have lowered the earnings of the bottom third. Other factors for which we do not yet have good measures of their impact (increased wage theft, the increased share of workers without effective legally protected rights due to their immigration status, and employee misclassification) likely play a role as well. In contrast, our analysis of data (in a section below and in Appendix A) related to automation and skill-biased technological change finds that these factors have had no impact on the suppression of median wages for at least the last 25 years.

Centering power and policy, not apolitical ‘market forces,’ in debates over U.S. wages

The large increase in inequality in the U.S. economy coincided with a pronounced political movement that called for increasing the reach and influence of markets in American life. This movement, known as market fundamentalism and often shorthanded as neoliberalism, has a long history in both U.S. and international policy debates. By the late 1970s, it achieved great prominence, even within the Democratic Party. Neoliberalism’s belief that markets are more efficient and effective than alternative instruments for distributing resources and organizing economic life led it straight to many of the policy recommendations that drove the rise in inequality. Neoliberals, for example, see minimum wages as an inefficient friction in otherwise competitive and efficient labor markets. So, minimum wages have been allowed to be battered by inflation.

The neoliberal policy agenda has often had its most enthusiastic proponents among economists. Under the influence of neoliberalism the economics profession, encompassing both the liberal and conservative wings, shed many older but supremely valuable insights about the importance of institutional checks on markets (especially labor markets) and began analyzing all labor market developments through the lens of textbook competitive models. In these models, the great wage deceleration for the vast majority of workers after 1979 and the resulting rise in inequality could only have happened if impersonal market forces shifted relative demand or supply curves for different sorts of labor.

The mistake of assuming that markets are always well characterized by the simplest competitive models of textbooks proliferated well beyond the labor market. With regard to product markets, the assumption led economists to argue for a retreat from robust anti-trust enforcement and for the deregulation of industries in sectors such as trucking, airlines, interstate busing, and utilities. The assumption that financial markets were competitive led economists to argue for financial deregulation. The promotion of shareholder primacy, that corporations and executives should only advance the profit needs of shareholders, was an important component of this market fundamentalism.

But the greatest damage occurred in labor markets. The focus on labor market competition led to the promotion of “labor flexibility” to achieve growth; this policy agenda sought to weaken collective bargaining, worker protections, and the social safety net (e.g., unemployment insurance). If your model says that only apolitical market-driven shifts of demand and supply curves can explain wage and employment trends, then what might these forces be? As wage suppression took hold, the consensus of elite economists, both liberals and conservatives, excused it as the result of computer-driven automation, a factor we would neither want to nor could restrain. In this scenario, the sole answer is to provide more skills and college education for the workers who have skill deficits—or essentially telling workers that they themselves are to blame for their loss of quality jobs.

But these explanations just don’t fit the data, and when data and model conflict, the wise move is to follow the data. So, if the neoliberal analysis fails to explain wage trends, then the resulting neoliberal policy recommendations should be jettisoned. If we manage to do this, our analysis of just what has happened to U.S. wages and inequality will be stronger and provide a better basis for fixing these issues going forward.

A good example of how the policies we have adopted rather than markets explain wage trends can be found by looking at the wage gaps between workers of different races, genders, and ethnicities. Understanding wage suppression as the result of the exercise of power in labor markets widens our understanding of the potential sources of these long-standing race and gender disparities, gaps that widened during the coronavirus pandemic. The systemic racism that slots minority workers into lesser-paid jobs has made these workers the primary victims of the systematic weakening of worker power. Consequently, one of the key mechanisms to lessen racial and gender inequities is to restore worker power generally as well as to shape policy to ensure all workers have access to good jobs.

This paper’s analysis complements and points in the same direction as other recent research that has focused attention on worker power. For instance, Stansbury and Summers (2020) also argue that reduced worker power explains sluggish wage growth and a declining labor share of income. New empirical examinations of employer monopsony power have identified a growing (at least since the late 1990s) and pervasive employer ability to mark down wages from 20% to 50% and to exert more power over low-wage workers than others. This new monopsony literature provides a top-down analysis, estimating the aggregate potential employer power to suppress wages and then examining the contributing role of countervailing forces like unionization, high-pressure labor markets, and high values of minimum wages in explaining an aggregate net metric of employer power. In contrast, we provide a bottom-up analysis examining the impact of many specific factors and gauging their contribution to the overall divergence between productivity and median compensation growth.

Joseph Stiglitz (2012, 2021) has long focused on power in markets, emphasizing both product market monopoly power and the weakening of employee power relative to employers. He recently provided an analysis similar to the framework of this paper:

The commonsense statement that employers have power over their employees has long been heretical in the economics profession…. More and more, firms have demonstrated high and increasing levels of market power. At the same time, the bargaining power of workers has weakened…. his imbalance of market power has consequences…. It enables firms to suppress wages of workers below what they would be in a competitive marketplace—contributing to the inequality crisis facing the country…. Employers and employees need to be able to bargain on more-equal footing. (Stiglitz 2021)

Our research and these other recent findings demonstrate that employer power is ubiquitous in labor markets, and that wages will be lower and wage growth suppressed absent institutions and policies that provide countervailing power. In other words, employer power is a constant of modern labor markets, but what has changed over the past generation or two is the erosion of institutions and policies—high-pressure labor markets, robust enforcement, unions, and meaningful minimum wages—that once provided that countervailing power.

The paper proceeds as follows. The first step is examining the wage and profit trends that any theory of wage suppression needs to explain. The second section assesses the conventional explanation of “skill-biased technological change”—namely, that in the face of rapid technological change or automation workers lack the skills necessary for more modern production systems. The third section identifies the six factors, from excessive unemployment and eroded collective bargaining to shifts in corporate structures, that we believe much better explain wage suppression. The final section reviews how this paper fits into the overall literature on wage inequality and draws on the estimated impact of the various factors to establish how much they explain the overall divergence between productivity and median hourly compensation as well as the growth of the 50/10 wage gap and changes of the 10th percentile wage.

Wage trends and patterns to be explained

There are three remarkable disparities in growth of wages by workers’ wage rankings that policymakers need to understand and economists need to explain: the one between the highest earners (the top 1% and top 0.1%) and other high-wage earners; the one between high-wage and middle-wage earners (the 95/50 or the 90/50 wage gaps); and the one between middle- and low-wage earners (the 50/10 wage gap). In addition, a theory about wage trends will need to explain the decline in the share of overall income accruing to labor, since this drop saps wage growth; the differing growth rates by educational credential, especially four-year college degrees; the growing divergence between typical workers’ pay (including both wages and benefits) and economywide productivity; and the widening wage gaps that appear between workers of different races, genders, and ethnicities.

Wage growth trends by percentile

Below we delve into some detail in these trends. The rough summary of inflation-adjusted wage growth, detailed below, is as follows. Between 1979 and 2019 (the end of the last business cycle), inflation-adjusted annual wages at the very top have grown tremendously. Those in the top 1% enjoyed 160% growth, and those at the very top—the top 0.1%—experienced growth of 345%. Growth was much slower at the 95th percentile—63% (using hourly wage data), slower still at the 50th (15%), and a snail’s pace at the 10th (3%)—though it is worth noting that growth rates at the middle and the bottom were not remarkably different since the late 1980s. Two key wage gaps have grown since the late 1980s: the one between the top and very top on the one hand and all other earners, including even those at the 95th percentile, on the other, and the gap between high earners and middle earners, illustrated by the ratio of wages at the 95th (or 90th) percentile and the median wage.

Wages at the top—the upper 1% and 0.1%

One of the trends that went unrecognized and unexamined in the mainstream labor economics literature for decades was the remarkable growth for those in the upper 1% and the even faster growth among those in the top 0.1% of wage earners. This growth in wages for the highest-earning households is a key cause of the better-known phenomenon of growth in the household incomes of the top 1%, a finding popularized by Occupy Wall Street and based on the well-known data developed by Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez (2003). The headline Piketty and Saez data are for households (“tax units” to be precise, but importantly they are not for individual workers) and include both wages earned by household members but also other income such as dividends, capital gains, and business income. However, one can analyze data to focus solely on wage and salary income of individual earners. Such an examination also shows superlative growth at the very top and demonstrates the importance of the upward redistribution of wage and salary income to the overall growth of top 1% household incomes.

Figure A, based on Social Security Administration data (see Mishel and Kandra 2020 for details), shows wage growth by the differing wage groups, including those at the top and very top. The Social Security data include all W-2 earnings as reported by employers (including the value of realized stock options and vested stock awards received by executives). Between 1979 and 2019, annual wages for the top 1% grew 160%. The wage growth of the top 0.1%—345%—is listed but not represented on the graph because it is on such a different scale.

In contrast, the wages of the bottom 90% grew by just 26% over those 40 years, with most of the growth occurring in a couple of brief and discrete periods of sustained low unemployment. The total wage growth in the 1995–2000 and 2013–2019 periods was 20%, roughly three-quarters of the cumulative wage growth for the bottom 90% over the entire 1979–2019 period. High earners in the 90th to 95th percentiles had wage growth faster than the vast majority (up 52%) but nowhere near that of those at the very top.

The share of all wages earned by those in the top 1% nearly doubled from 1979 to 2019, from 7.3% to 13.2%. Correspondingly, the share of wages earned by the bottom 90% eroded throughout this time, from 69.8% in 1979 to 60.9% in 2019 (Mishel and Kandra 2020). Had this redistribution not taken place, wages for those in the bottom 90% could have grown by 44.6%, 18.5 percentage points more than was the case.2 In short, the redistribution of wages from low and middle to high percentiles has greatly mattered for what the vast majority took home in their paychecks.

Wage gaps for most everyone else: The 95/50 and 50/10 gaps

Outside the top 1%, the clearest growth in wage gaps between percentiles in the wage distribution has been between high earners and middle-wage earners. This is often illustrated by the wage gap between the earners at the 95th percentile and the median (50th percentile) worker. Perhaps surprisingly to some, wage gaps in the bottom half of the distribution of wages (those between middle-wage and low-wage workers) have not grown for more than 30 years (basically since 1987–1988).

Figures B and C show the trends in the 95/50 and 50/10 wage gaps by gender. One striking dimension of the growth of wage inequality is the persistent, continuous growth of the wage gap between those higher up, the 95th percentile, and middle-wage workers since 1979, among both men and women (Figure B). The growth of the 95/50 wage gap has accelerated over time, growing faster in the more recent period (either 1995–2019 or 2000–2019) than it did earlier.3 The growth of the gap between those at the top and the middle of the wage distribution, and its acceleration after the late 1990s, is one of the key wage patterns that need to be explained.

In contrast, there has been little change (or an actual decline) in the 50/10 wage gap since the late 1980s (Figure C). The log 50/10 wage gap (using the same data as in the figure) grew from 0.57 in 1979 to 0.75 in 1987 and then declined to 0.68 in 2000 and to 0.65 in 2019. There was a jump in this gap in the early and mid-1980s, especially among women. The fact that there was a much more modest increase in the 50/10 wage gap among men provides an important clue as to the source of this rising gap: the erosion of the real value of the federal minimum wage. Federal inaction on the minimum wage in the 1980s had a much larger impact on low-wage women than low-wage men because women are far more likely to earn wages low enough to be affected by the minimum wage. The importance of institutions (the federal minimum wage) in this case will become a pattern as we look at the data on wage gaps and their causes more generally. The decline in the 50/10 wage gap since 1987–1988 presents a severe challenge to explanations of wage inequality focused on skill or education premiums, since it appears that those with the least education fared somewhat better than those with middling educations. The fact that the 50/10 wage gaps were relatively constant since the late 1980s indicates that a similar, or related, set of forces were at work suppressing wages at both the bottom and the middle.

Wage differences by education

The academic and policy debate about wage inequality has often focused on wage gaps across education groups, especially between those with a (four-year) college degree versus those without. Growing education wage differentials have been the basis of the premier conventional explanation of growing wage inequality, which attributes it to “skill-biased technological change.” This theory holds that labor markets are well characterized by competitive models and that an exogenous technology shock—often identified as automation driven by information technologies—has reduced the relative demand for workers without a college degree relative to their college peers, leading to widening inequality between wage earners. The policy corollary to this view has been a call for workers to get college degrees.

The automation-driven skills-gap narrative is critically examined in a later section and in Appendix A. In this section the basic contours of education wage gaps over time are examined. The key metric for capturing education wage differentials is the college–high school premium, or simply the college wage premium, the difference in hourly wages between a college graduate and a high school graduate, controlling for demographic characteristics such as gender, race, and experience. The trend in the college wage premium since 1979 is shown in Figure D.4

The college wage premium grew sharply in the 1980s and early 1990s, the era when research arguing for a skills-based explanation of wage inequality grew in prestige. However, growth in the college wage premium has been quite modest since the mid-1990s: It rose by 17.5 log points over the 16 years between 1979 and 1995 but by only 6.4 log points in the 24 years from 1995 to 2019. In annual terms the premium grew 1.1% in the 1979–1995 period but just 0.3% between 1995 and 2019—and just 0.1% per year in the 2000s. The deceleration did not occur because there was an upsurge in the availability of college graduates; in fact, Autor, Goldin, and Katz (2020) show that the relative supply of college graduates grew more slowly in the 1999-2017 period than in the earlier 1979–1999 period.5

It is worth noting that other education wage differentials, such as that between high school graduates and those who left high school and between associate-degree holders and high school graduates, have been fairly stable since 1995. For example, the wage gap, regression-adjusted, between those with a high school degree and those not completing high school (or a GED) rose only slightly between 1979 and 1987—up 2.6 log points—hardly sufficient to explain the sharp rise in the 50/10 wage gap over that period. Between 1987 and 2018 this wage gap shrank by 3.0 log points, reversing the entire 1979–1987 rise and leaving the wage gap where it was in 1979. Since there was hardly any growth in education wage gaps among the bottom three education groups, any explanation for wage gaps in the bottom half that relies on education gaps has little explanatory power.

The gap between productivity and median hourly compensation

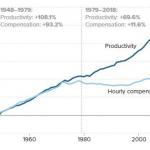

The last four decades have seen a systematic divergence between the growth of economywide productivity (the amount of income generated in an average hour of work) and the growth of hourly compensation (wages and benefits) for typical workers. We proxy the wages of “typical” workers as either wages for nonsupervisory workers (roughly 80% of the private-sector workforce) or wages for the worker earning the median wage. Figure E, which shows the growth of productivity and the typical worker’s hourly compensation since 1948, uses the hourly compensation of production-nonsupervisory workers because that is the only series available for the entire period since 1948.6 While productivity and a typical workers’ compensation grew in tandem over the 1948–1973 period, they diverged thereafter, splitting entirely after 1979. In the latter period productivity decelerated significantly, but much more rapid deceleration (or even stagnation) occurred in a typical worker’s compensation. Productivity grew 108.1% from 1948 to 1979, accompanied by 93.2% growth in a worker’s compensation. Between 1979 and 2018 productivity grew 69.6% (1.2% annually) further, but a typical worker’s compensation (wages and benefits) grew only by 11.6% (0.24% annually).

This divergence was first pointed out in the early 1990s (Mishel and Bernstein 1994) to demonstrate that stagnant wages for the typical worker over the previous decade or so could not be explained solely by the slowdown of productivity growth. Bivens and Mishel (2015) examined the wedge between typical workers’ pay and productivity and decomposed the main factors generating it. Once technical influences like differing price deflators were accounted for, the remaining wedge between pay and productivity growth was driven by two facets of inequality: the decline in labor’s share of income (particularly in the 2000s) and the growth of inequality of compensation, such that compensation grew far faster at the very top, as shown above.7 In other words, the factors driving inequalities in the labor market are responsible for workers’ inability to make gains commensurate with productivity growth. Whether workers make wage gains commensurate with future productivity growth will depend on whether we prevent this ongoing, and eminently preventable, growth in wage inequality. These dynamics will, in turn, dictate the extent of inequalities across households.

What has this divergence meant for a typical worker’s compensation? Building on the Bivens and Mishel (2015) analysis, we calculate that between 1979 and 2017 economywide productivity rose 68.1% while median hourly compensation rose 13.0% (the median hourly wage rose 12.2%), yielding a 55.2 percentage point divergence. Excluding the impact of differing price deflators (using the same index to deflate both productivity and median hourly compensation) yields a 43 percentage point divergence. Thus, the pay for typical workers would be more than 40% higher today if inequality had not risen over the 1979–2017 period. In the final section we examine the impact of particular factors to gauge whether their cumulative impact can explain the productivity–median compensation divergence. We use the 1979–2017 period as the benchmark, since that period corresponds to some key estimates of the impact of particular factors on median wages.

The decline in labor’s share of income

One of the trends that alerted analysts to the erosion of worker bargaining power and the corresponding strengthening of employer bargaining power has been the erosion of labor’s share of income in the 2000s. The distributional conflict between workers and employers (or capital and labor shares) is best examined in the corporate sector, where all income is divided between compensation going to workers and income accruing to owners of capital. Focusing on the corporate sector hence avoids issues of having to decide whether some other form of income—”proprietor’s income,” or income of noncorporate businesses—is labor or capital (see Bivens 2019 for measurement details).

The trend in the labor share of corporate-sector income is presented in Figure F.

The data clearly show a lowering of labor’s share in the 2000s, even when cyclical ups and downs are factored in. In business cycles before the 2000s, labor’s share generally rose during recessions, as profits fell, but then dropped sharply in early recoveries, as high unemployment weighed on wage growth even as the economy and profits recovered. By the time of each business cycle peak, labor’s share had generally recovered its previous peak. After 2000, though, labor’s share has often not recovered its previous peak following recessions. For example, it fell from 82.4% in 2000 to 77.9% in 2007, the last year before the Great Recession, and by 2016, when unemployment had reached levels comparable to what had prevailed in 2006 and 2007, it remained roughly 2.5 percentage points below its 2007 level. The fall in labor’s share from 82.4% in 2000 to 75.5% in 2016 is the equivalent of an 8.4% across-the-board cut in compensation for every employee; equivalently, it would require an across-the-board compensation boost of 9.1% to restore labor’s share to its 2000 level.8 This computation may exaggerate the impact of labor’s falling share, since 2000 was a near high point for it historically, driven in part by unemployment falling to its lowest level in decades (4.0%). However, the unemployment rate in 2018 and 2019 also averaged below 4.0%, and labor’s share ended 2019 at 77.3%, well below 2000’s level. This shift toward greater capital income and returns is even more impressive given that real interest rates have fallen sharply in recent years, a development that should (all else equal) be accompanied by a lower return to capital (Farhi and Gourio 2018).

Wage disparities by race and gender

Race and gender wage disparities have been persistent and insidious and reflect key dynamics that need to be understood in any analysis of the labor market.

Most measures of overall gender wage inequality have fallen over the last four decades. Figure G traces the gender wage gap over 1979–2019 in two ways, the percentage gap between the male and female median wage and the unexplained (log) percent of the gender wage gap (on average) after controlling for race and ethnicity, education, age, and geographic division. By both measures the wage disparities between men and women have substantially declined. The gap at the median has been cut in half, from 36.7% in 1979 to 15.8% in 2019, and the gap that is unexplained fell from 37.7 to 22.6 log points.

Conversely, most measures of Black–white wage disparities have grown in the last four decades (Figure H) and have exacerbated the growth of overall wage inequality (Wilson and Rodgers 2016; Wilson 2020). The increase has not occurred along a straight line, however. During the early 1980s rising unemployment, declining unionization, and policies such as the failure to raise the minimum wage and lax enforcement of anti-discrimination laws contributed to the growing Black–white wage gap. During the late 1990s the gap shrank in part due to increases in the minimum wage and in part to tighter labor markets, which made discrimination more costly to employers. Since 2000 the gap has grown again. As of 2015, relative to the average hourly wages of white men with the same education, experience, metro status, and region of residence, Black men made 22.0% less and Black women 34.2% less. Black women earn 11.7% less than their white female counterparts. The median Black worker’s hourly wage rose only 5.3% from 1979 to 2019, lagging far behind the 20.0% hourly growth enjoyed by the median white worker. The 7.6 log point growth of the “unexplained” portion of the Black–white average wage gap suggests that the economic bite of discriminatory pay practices has grown and accounts for a large share of the relative wage growth disadvantage of Black workers.9

The causal connection between racial, gender, and ethnic wage growth differences and wage growth differences by percentiles likely runs in both directions. On the one hand, because white women and Black workers tend to be disproportionately concentrated in the bottom 90% of the wage distribution, any force that suppresses wages for the bottom 90% will make them lose ground to white men and whites overall, all else equal. In a study of racial differences in household income, for example, Manduca (2018) finds that the percentile rank of the median Black household in the overall household income distribution climbed rapidly between 1968 and 2016, from the 24th to the 36th percentile. Yet because inequality concentrated gains in the top half of the income distribution over that time, and because white households were disproportionately concentrated in the top half, the income gap (measured in dollars or as a percentage) between white and Black households actually grew. So, a redistribution of income or wages to top and very top earners can increase gender and racial inequities even when Blacks and women achieve better equity among the bottom 90%.

Conversely, racial and gender differences in pay could in theory feed through to measures of inequality by percentile. For example, if the gap in wages paid to otherwise-equivalent Black and white workers can be pocketed entirely by the employers of Black workers, then this pay-setting discrimination would translate one-for-one into lower measured wages of typical workers of all races. If, on the other hand, pay-setting discrimination reflects employer preferences for white workers over Black workers, then some of this Black/white wage gap is a de facto transfer from Black workers to white workers. Less mechanically, if the maintenance of racial and gender wage gaps fosters division and hamstrings collective cross-race and cross-gender efforts to raise wages in workplaces, then these gaps could be a powerful force for employers looking to keep overall wages suppressed.

The failure of automation and skill gaps to explain wage suppression or wage inequality

That a huge proportion of U.S. workers have “skills deficits,” i.e., lack the skills necessary to deal with technological change (including primarily automation of the tasks performed by workers without a four-year college degree), has been the predominant explanation offered by economists, pundits, policymakers, and the media to explaining sluggish wage growth and inequality in the United States, at least until recently (see Box A for why we focus on “automation” rather than a more general “technological” explanation). This is the skill-biased technological change hypothesis, which points to the increased use of computer equipment in the workplace and the onset of the information age. One version, focused on education wage gaps, argues that computerized automation has made more-educated workers—generally referring to those with at least a four-year college degree—more valuable to employers and has correspondingly reduced the value of those without a college degree (Katz and Murphy 1992; Goldin and Katz 2007, 2008). This growing wage gap between college-educated and non-college-educated workers—the college wage premium—is used to explain rising wage inequality between high earners and the majority of earners who lack a four-year college credential (62% of earners in 2019, down from 82% in 197910).

BOX A

The difference between ‘technology’ and ‘automation’ as a driver of inequality

Economists inadvertently talk past the public when they refer to “technology” driving wage inequality when they are really talking about the skill-biased technological change thesis, which centers on workplace automation of tasks performed by workers without a four-year college degree. Technological change is a broad term that applies to everyday life and involves communications technology, technology embedded in consumer products (e.g., phones, cars, energy-saving appliances), and other technologies separate and independent of workplace automation. There may be rapid change in the technologies observed in consumer products or in telecommunications even though workplace automation—and its relative effect on workers with different education credentials—is proceeding at a historically average or slower pace. Changes in communications technology may help fuel globalization and may help enable domestic outsourcing (“fissuring”) to be undertaken more cheaply, but these channels through which technology may affect labor market trends are quite different than those sketched out by theories of skill-biased technological change in the workplace.

Skill-biased technological change represents automation, the change in production methods where machinery and software replace the tasks formerly performed by workers without a four-year college degree, thereby generating a new mix of the human capital needed (more “skilled labor,” less “less-skilled” labor).

A second version of the automation story, frequently referred to as the “job polarization thesis,” argues that technological change

has increased the value of abstract reasoning, of creativity, of expertise, of judgment and devalued a lot of skilled work that people did that followed well-understood rules and procedures. So that would be many clerical jobs, phone answering jobs, calculating, accounting, bookkeeping, copying, and filing, but also many production jobs, which often involved skilled, repetitive tasks. But increasingly once we understand the rule book for that type of work, it’s feasible to encode it in software and have it executed by machines or by computers.” (David Autor, interviewed by Greenhouse 2020)

This type of automation sees the replacement of human labor by computers or other modes of automation as not just falling along the lines of greater/fewer education credentials (whether a worker has a college degree or not). Instead, occupational susceptibility to having tasks automated is said to be “polarized”—middle-wage occupations specializing in routine, automatable tasks shrink while employment expands in both higher-wage “abstract reasoning” occupations and in lower-wage non-routinized occupations.

These versions of skill-biased technological change portray the cause of wage suppression and wage inequality as due to a factor, automation, that is both inevitable (one can’t stop technology’s forward march) and desirable (after all, technological change is a key driver of rising living standards). Thus, the resulting economic adversity for some workers is the unfortunate byproduct of a dynamic that one would neither want to nor could change. Given this view, the only appropriate remedy is to adapt to automation, primarily by upgrading workers’ skills and education and perhaps by providing a more adequate safety net for workers temporarily displaced.

The skills narrative is the premier explanation of wage inequality that relies on the existence of competitive labor markets and sees a role for policy only in fostering skills development—not in boosting workers’ bargaining power or mandating changes in corporate practices. As such, the failure of the skills narrative to explain wage suppression and wage inequality also reflects the failure of analyses based on equal bargaining power between employers and employees and competitive labor markets to adequately address one of the most salient features of the economy over the last four decades.

As examined in detail in Appendix A, skill-biased technological change has always been a weak explanation for the wage trends since 1979, but is a prima facie implausible explanation for the trends since the mid-1990s or since 1999. None of the basic indicators of automation’s impact and of skill deficits used to establish these narratives has been evident over the last 25 years. Consequently, there is no basis for considering automation-driven skill-biased technological change as a significant factor in wage suppression or the growth of wage inequality since the mid-1990s—and we assign it an impact of zero since 1995 in our analysis below.

The extreme weakness of the hypothesis is why the consensus, at least of center-left economists, no longer highlights it in discussions of wage problems. Lawrence Summers went so far as to say:

I am concerned that if we allow the idea to take hold that all we need to do is there are all these jobs with skills and if we just can train people a bit then they will be able to get into them and the whole problem will go away. I think that is fundamentally an evasion of a profound social challenge. (Summers 2015, 75–76)

The following sections, drawing on Appendix A, offer some critiques of the skills narrative, focusing particularly on its inability to explain wage trends since the mid-1990s.

Omissions in the skills-based wage-gap story

One problem with the automation narratives is that they ignore, or perhaps fail to address, important dimensions of wage suppression and wage inequality. For instance, they sidestep the superlative wage growth of the top 1% (and the top 0.1%) and the corresponding upward shift of 6 percentage points of aggregate earnings to the top 1% between 1979 and 2019 (Mishel and Kandra 2020). The growth of wages for the top 1% primarily reflects the growth of executive compensation and the expansion of the financial sector (and its high earners). Similarly, the narratives accord no attention to the erosion of labor’s share of income, and the data show that the link between automation and the decline of labor’s share is at least as inconsistent with real-world data as is the link between automation and wage inequality (Stansbury and Summers 2020). These are substantial oversights.

Evidentiary problems with the skills-gap, or automation, hypothesis

Recent research by the leading proponents of the skill-biased narrative (Autor, Goldin, and Katz 2020) demonstrates the failure of this hypothesis to contribute to our understanding of wage suppression since the mid-1990s. The three biggest evidentiary failures are the following.

There has been little growth in the college wage premium

Autor, Goldin, and Katz (2020) note that “returns to a year of college rose by 6.5 log points, from 0.076 in 1980 to 0.126 in 2000 to 0.141 in 2017.” Yet note the slowdown from the 1980–2000 period to the 2000–2017 period. In the former period, the log college wage premium rose 0.0325 percentage points each year, far faster than the 0.0088 percentage point increase each year between 2000 and 2017. This represents a 70% reduction in growth. Given that the log 95/50 wage gap grew faster between 2000 and 2019 than in 1979–2000 (see Appendix Figure A), it is evident that the education wage gap has not driven wage inequality in the top half since 2000.

There has been a sharp deceleration in automation-driven relative demand for college graduates since the mid-1990s

The substantial deceleration in the college wage premium, even as the supply of college graduates slowed, implies a dramatic slowing in the growth of relative demand for college graduates. As Autor, Goldin, and Katz (2020) note:

he model’s results…divulge a puzzling slowdown in the trend demand growth for college equivalents starting in the early 1990s. Rapid and disruptive technological change from computerization, robots, and artificial intelligence is not to be found though the impact of these technologies may not be well captured by this two-factor setup.

Their results (based on Autor, Goldin, and Katz, Table A2) show a deceleration in growth of relative demand for college graduates in the 1999–2017 period relative to earlier periods: a 45.8% deceleration relative to the 1979–1999 period and a 41.8% deceleration relative to the longer 1959–1999 period. The period since 1999, therefore, has been one featuring a historically small impact of automation on (relative) demand for college graduates.

Autor (2017) provides similar findings in an update of the Katz and Murphy (1992) metric of relative demand for college graduates and dates the slowdown to the mid-1990s.

If automation’s impact has been far less in the last 25 years than in earlier decades, it cannot explain the ongoing strong, even faster, growth of wage inequality in the top half, illustrated by the growth of the 95/50 wage gap.

There has been no expansion of the wage gap in the bottom half since 1987

In the skills-gap story, the more education workers have, the more they are in demand and the higher their wages. Yet over the last three decades there have been no increases in the wage gaps between those with some college, those with a high school diploma, and those who left high school. Similarly, that the wage gap between median (50th percentile) workers and low-wage (10th percentile) workers has been stable or declining since 1987 stands as a long-standing critique of the education wage-gap hypothesis (Mishel, Bernstein, and Schmitt 1997a; Card and DiNardo 2002; Acemoglu and Autor 2012).

Evidentiary problems with claims that ‘occupational polarization’ of labor demand can explain wage patterns

As mentioned earlier, a recent twist on the traditional story of skills-driven wage trends is the idea of labor market “polarization.” In this view, labor demand has not been rising commensurately with every level of education; rather, there has been an increase in labor demand for high-skill occupations but also for nonroutine manual occupations generally associated with low wages. The losers are those with routine, nonabstract skills that have traditionally been associated with middle-wage occupations, such as in manufacturing.

There are two clear empirical problems with the polarization narrative as an explanation for the wage trends over the full 1979–2019 period.

There has been no occupational employment polarization since 1999

Most strikingly, Autor (2010) and Acemoglu and Autor (2012) document that job polarization has not been evident since 1999:

rowth of high-skill, high-wage occupations (those associated with abstract work) decelerated markedly in the 2000s, with no relative growth in the top two deciles of the occupational skill distribution during 1999 through 2007, and only a modest recovery between 2007 and 2012. Stated plainly, the U-shaped growth of occupational employment came increasingly to resemble a downward ramp in the 2000s. (Autor 2014)

A “downward ramp” and the absence of a “U-shaped growth of occupational employment” amount to an acknowledgment, although offered in a less-than-direct fashion, that job polarization was not present between 1999 and 2012.

Occupational employment patterns do not correspond to wage patterns

The job polarization narrative relies on mapping occupational employment patterns to explain wage trends. But surprisingly, the polarization literature has never presented evidence that these occupational employment shifts directly affect wages. And indeed, they don’t. Mishel, Shierholz, and Schmitt (2013) show that in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, changes in occupational employment shares (whether employment in an occupation expands or contracts relative to other occupations) were not related to changes in relative wages by occupation (whether wages rose or fell in that occupation relative to wages of other occupations). It is also worth noting that middle-wage occupations have shrunk and higher-wage occupations have expanded since the 1950s, but median wages and wage inequality have risen and fallen over this time with no apparent correspondence to employment polarization trends.

If occupational employment patterns do not directly correlate with occupational relative wages, then the narrative that employment polarization reflects a shift in the relative demand for specific types of skills makes little sense; shifting relative labor demand curves should cause both employment and wages to move together. Moreover, if occupational job polarization does not shape relative occupational wages, then it is certainly not much of an explanation for wage inequality.

A more convincing theory of sluggish wage growth and inequality in the U.S.: Policy-driven wage suppression

If forces unrelated to policy decisions, particularly automation, do not seem to be driving wage trends, what are the factors leading to wage suppression? Our answer is that there has been an intentional policy assault—including policy forbearance in the face of new anti-worker business practices—that diminished the institutional sources of leverage and bargaining power for typical workers in the labor market. The point was to suppress labor costs. This policy assault (acts of commission and omission, such as failing to update labor law or the value of the minimum wage) either directly undercut these institutional sources of power or accommodated employers’ efforts to undercut them. Business forces were secure knowing that policymakers (legislators, executive branch officials, and judges) would not change legislation, enforcement priorities and effectiveness, or legal interpretations to countermand this assault on a typical workers’ power in the labor market.

Why this policy and corporate assault began when it did, and why it was successful politically, are questions mostly outside the bounds of this paper. (See two relatively recent books by Hacker and Pierson (2011, 2020) for the political science explanations.) Among academic and policy economists starting in the 1970s, policies promoting wage suppression were forwarded as the solution to decelerating productivity growth, accelerating inflation, and high unemployment, where the goal was to improve aggregate efficiency and growth. But it did not work: Economic growth between 1979 and 1995 was historically slow, and the brief pickup between 1995 and 2000 was driven by a burst of business spending to connect to the internet and the decision by the Federal Reserve to shunt aside inflation fears and allow unemployment to fall to historically low levels. Slow productivity growth reasserted itself quickly in the 2000s as the burst of information-technology investment receded.

BOX B

Wage suppression and the upward distribution to the top 1%

The data are clear that wage growth for the vast majority of U.S. workers decelerated radically in the post-1979 era. This near-stagnation of wages cannot be nearly fully explained by the slowdown in the economy’s overall ability to pay higher wages (measured, for example, by growth in economywide productivity). Overall economic growth did slow significantly post-1979, but growth for the bottom 90% of wage earners slowed far more. This pattern left a large excess available for the top 10% to grab, and most of it went to the top 1% and, especially, the top 0.1%. While this paper does not undertake to directly explain the growth of wages at the very top—those of the top 0.1% and 1%—we would argue that this growth is just the mirror image of wage suppression at the bottom. The forces that weighed on wage growth for the majority (excess unemployment, stagnation of the minimum wage, deunionization) largely do not slow wage growth for the top 1%; instead, they just allow more income (income, wages, and profits that are not going to typical workers’ paychecks) to be claimed by the very top. In a sense, the wage suppression felt by the bottom 90% was zero-sum (or even negative sum), as their loss financed a sharp redistribution of wages and incomes to the very top.

As Bivens and Mishel (2013) argue:

The increase in the incomes and wages of the top 1% over the last three decades should be interpreted as driven largely by the creation and/or redistribution of economic rents, and not simply as the outcome of well-functioning competitive markets rewarding skills or productivity based on marginal differences. This rise in rents accruing to the top 1% could be the result of increased opportunities for rent-shifting, increased incentives for rent-shifting, or a combination of both. Second, this rise in incomes at the very top has been the primary impediment to having growth in living standards for low- and moderate-income households approach the growth rate of economywide productivity. Third, because this rise in top incomes is largely driven by rents, there is the potential for checking (or even reversing) this rise through policy measures with little to no adverse impact on overall economic growth.

As evidence for this view, Bivens and Mishel highlight the growth of chief executive officer (and other executive) pay and the incomes of financial-sector professionals. A vast body of research demonstrates that no plausible force coming from the interplay of competitive markets could account for the explosive income growth of these actors. These are not the “just deserts” of the high earners reflecting their heightened productivity.

The opinions of academic economists aside, the larger political dynamics of why this wage-suppression campaign began and became a key priority for corporate and business interests in the 1970s are clearly important. Levy and Temin (2007), Bivens (2010), and Mishel, Rhinehart, and Windham (2020) provide an overview of this period and document the concerted shift of the corporate sector away from the “Treaty of Detroit” regime established in the early 1950s that tolerated (or even encouraged) collective bargaining and toward policies maximizing shareholder value and deregulation. The falling profitability of the corporate sector in the 1970s was clearly a part of this dynamic, as was the rising ease of moving production offshore.

While the root causes and the political support behind the policy assault on bargaining power are not addressed here, a growing body of evidence shows that the specific policies launched in this attack can explain the overwhelming majority of wage suppression experienced in recent decades. This section examines these policies and estimates the impact of each. When added together, as we do in the final section, the impact is large enough to explain the lion’s share of the 43% difference since the late 1970s between the growth of median hourly compensation and economywide productivity.

Austerity macroeconomic policy: Excessive unemployment

The Federal Reserve Board’s dual mandate is to pursue the maximum level of employment consistent with stable inflation. However, since 1979 the Fed’s actions suggest that it took the inflation mandate more seriously, thereby tolerating (by failing to lower) or actually generating excessive unemployment for extended periods in the name of keeping inflation tame. Whenever an economic expansion pushed unemployment down, the Fed often feared that tighter labor markets would mean that workers, endowed with more leverage since they were now in a better position to quit or strike, would demand higher nominal wages, in turn putting upward pressure on inflation.

Wage growth resulting from tight labor markets can indeed feed into price growth, and so sufficiently empowered workers may demand even higher wages, allowing wage/inflation momentum to build. The policy recourse for stopping the wage/price spiral has traditionally relied on the Fed raising interest rates to slow the expansion and stop the downward movement of unemployment.

Presumably in this policy vision there is a sweet spot where workers can experience decent wage growth without fostering unsustainable inflationary pressure. But nobody knows for sure beforehand where that level is, and efforts to empirically identify the economy’s “natural rate of unemployment” are notoriously imprecise (Staiger, Stock, and Watson 1997). Given this uncertainty, the Fed must exercise judgment in weighing the benefits of tighter labor markets against the risks of inflationary pressure. Too often in the post-1979 period, Fed policymakers have been so worried about the inflation risks and not impressed enough by the benefits of full employment that they have raised interest rates prematurely and cut expansions short before they generated decent wage growth. The result has been unemployment higher than it had to be to ensure stable inflation.

Historically, the anti-inflation orientation of the Fed was quite political and conscious of the institutional determinants of wage growth. Specifically, past Fed chairs, determined to keep wage growth “moderate,” explicitly saw the use of high unemployment as a means to restrain union-negotiated wage increases or even to seek union wage concessions.

Mitchell and Erickson (2005) characterized this policy orientation during the era of Paul Volcker’s chairmanship of the Fed (1979–1987), when there was a deep recession and a sharp reduction in unionization (40% of the erosion of unions over the 1979–2017 period occurred in 1979–1984):

Volcker viewed affecting union wage determination through monetary restraint as important for the Fed’s disinflation campaign. One commentator characterized the Fed chair’s view as founded on the idea that “inflation would not be securely defeated…until all those workers and their unions agreed to accept less. If they were not impressed by words, perhaps the liquidation of several million more jobs would convince them.” …Others at the Fed apparently had similar wage-push ideas. To Volcker, direct intervention in particular wage settlements was not desirable (and clearly not the province of the Fed). But a monetary squeeze that forced the union sector to hold down nominal wages in the hopes of preserving jobs was an appropriate policy instrument. Squeeze the unions and other wages (and prices) would fall into line.

Hooper, Mishkin, and Sufi (2019, 25) note that “since the 1980s the Fed focused much more on avoiding labor market overheating in order to stabilize inflation.” The discussion in Appendix B provides a further analysis of the Federal Reserve policy that maintained excessive unemployment.

Bivens and Zipperer (2018), analyzing the links between excess unemployment and wage growth, note that full employment (at least by the too conservative measure of matching actual unemployment to preexisting estimates of the “natural rate”) was the norm after World War II but became the exception after 1979. Between 1949 and 1979, the cumulative difference between the actual unemployment rate and estimates of the unemployment rate consistent with stable inflation—the “natural rate” or the NAIRU, the nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment—was negative 15.3 percentage points, meaning that on average actual unemployment was 0.52 percentage points below the estimated NAIRU each year. In contrast, between 1979 and 2017 the cumulative difference was positive 35.7 percentage points, meaning that actual unemployment was persistently above the estimated natural rate. This trend was not driven only by the Great Recession: Between 1979 and 2007 the cumulative difference was a positive 15.5 percentage points. Put another way, unemployment was 1 percentage point higher each year in 1979–2007 than in 1949–1979.

This consistent excess unemployment was deeply damaging to wage growth. Research indicates that a 1 percentage point drop in unemployment results in annual wage growth 0.5–1.5 percentage points faster for workers at the 10th percentile. For example, if annual real wage growth is 1%, then a 1 percentage point fall in unemployment would result in annual real wage growth rising to 1.5% to 2.5%. For workers near the median of the wage distribution, wage growth is faster by 0.4–0.9 percentage points, and for workers at the 90th percentile it is 0.3–0.5 percentage points faster. These estimates indicate that excessive unemployment generates increases in both the 50/10 and 90/50 wage gaps.11

Using the lower bound of the Bivens and Zipperer estimates to assess the impact of excessive unemployment on median and 10th percentile wages in the 1979–2017 period, we find excessive unemployment had lowered the median hourly wage by 12.2%. These estimated impacts of unemployment are far below those of Katz and Krueger (1999, Table 8), whose Phillips curve estimates using a 1973–1998 time series were double those of Bivens and Zipperer at the median and three times those at the 10th percentile.

However, to err on the side of caution we make an adjustment to our estimates of the wage impact of higher unemployment to account for the “flattening” of the Phillips curve in recent years (a lessening of the relationship between unemployment and wage growth): We apply one impact for the 1979–2007 years and a lesser impact for the 2008–2017 years.12 The coefficient on unemployment levels in regressions explaining wage growth is notably smaller in the time period after 2008.13 It should be noted that, as Hooper, Mishkin, and Sufi (2019) found, the “wage-Phillips curve…flattened significantly less and retained greater nonlinearity” than the price Phillips curve. However, one should be clear what is driving the flattening of the wage Phillips curves in the post-2008 period: the failure of high unemployment to force actual reductions in nominal wages in just a small number of years (2008-2014, mostly), a finding highlighted in Bivens (2019). If one removes this subset of years from the sample, the regression coefficient for the overall post-1979 sample is far closer to what one obtains from running the regression over the period from 1979 to 2007. It seems clear that this is the issue of “downward nominal wage rigidity bending the Phillips curve,” as expressed by Daly and Hobijin (2014). This implies that we are overcorrecting in our markdown of the impact of unemployment on wages post-2008; that is, we are understating the negative impact of high unemployment.

Taking this flattening of the Phillips curve into account we find that, if unemployment over 1979–2017 had averaged just the “natural rate” of 5.5% rather than 6.3%, median wages would have been 10.0% higher in 2017. If the unemployment rate had been held even lower, say 5.0%, median wages would have been 18.3% higher by 2017.

About a fourth of this impact is the result of the corrosive effects of the extended period of high unemployment following the Great Recession. In those years, the real culprit for keeping labor markets too soft to generate decent wage growth was not the Federal Reserve Board (the Fed actually tried hard to boost economic growth in those years). Instead, fiscal policymakers—both the Republican-led Congress and state and local governments after 2010—imposed historically contractionary degrees of spending austerity.

As analyzed in the final section, excessive unemployment’s impact on the median wage of 10.0% can explain nearly a fourth of the productivity–median compensation divergence of 43.0% and is a sizable factor expanding the wage gaps in both the bottom and top halves of the wage structure. For instance, excessive unemployment had a larger impact on low-wage workers, lowering the 10th percentile wage by 11.6% by 2017 and raising the 50/10 wage gap by 2.7 percentage points. If our analysis uses 5.0% rather than 5.5% as the full employment target, then the 10th percentile wage would have been 21.2% higher in 2017 absent excessive unemployment.

Because Black workers are disproportionately concentrated in the bottom half of the wage distribution, the corrosive effect on wage growth of excess unemployment falls more heavily on them. Wilson (2015) has found that the wage-depressing effect of each additional percentage point of unemployment is roughly twice as large for the median Black wage as for the median white wage. Wilson and Rodgers (2016) find that the wage penalty for the median Black worker relative to the median white worker increased by nearly 9 percentage points between 1979 and 2014. This growth in the Black–white wage gap could be entirely explained by excessive unemployment over this period, given the differing responsiveness of Black and white wages to unemployment.

Erosion of workers’ rights to form unions and bargain collectively

The erosion of collective bargaining has been a major factor that has depressed wage growth in the middle and drove the growth of wage inequality over the last four decades. In fact, the only factor having a larger impact is the excessive unemployment perpetrated by policymakers. The impact has been especially adverse for men because they were far more likely to be unionized in 1979 than women (31.5% versus 18.8%), so men had more to lose from the subsequent attack on unions and collective bargaining.14

That collective bargaining leads to more equal wage outcomes was firmly established by research by Richard Freeman and James Medoff in the late 1970s and popularized in their important book, What Do Unions Do?, published in 1984 (Jake Rosenfeld’s 2014 book, What Unions No Longer Do, provides an update of the issues). Consider first the ways that collective bargaining leads to more equal wage outcomes among unionized workers and in unionized industries and occupations.15 First, unions make wage differences between occupations more equal because they give a larger wage boost to low- and middle-wage occupations than to high-wage occupations. Second, unions have boosted wages for low-wage workers the most, and increases have been larger at the middle than at the highest wage levels, larger for Black and Hispanic workers than for white workers, and larger for those with lower levels of education. This pattern of wage increases narrows wage inequalities. Third, unions make wages of workers with similar characteristics more equal in union settings because wages are “standardized,” meaning that wages are set for particular types of work and do not vary across people doing the same work to the same degree as exists in nonunion settings. Fourth, unions have historically been more likely to organize middle-wage than high-wage workers, which lowers inequality by closing gaps between, say, blue-collar and white-collar workers.16 The union impact on inequality is even greater with compensation than with wages alone (Pierce 1999).

Research from the early 1990s documented that the erosion of collective bargaining was responsible for around a fifth of the rise in wage inequality among men in the 1980s (Card 1991; DiNardo, Fortin, and Lemieux 1996; Freeman 1991) but had a more modest impact on women’s wage inequality.

More recent research has incorporated an assessment of the impact of unions on nonunion workers’ wages—sometimes referred to as “spillover effects”—and finds a much larger impact. When the share of workers who are union members is relatively high, as it was in 1979, wages of nonunion workers are higher. For example, had union density remained at its 1979 level, weekly wages of nonunion men in the private sector would have been 5% higher in 2013, equivalent to an additional $2,704 in earnings for year-round workers; among those same workers but without a college education wages would be 8% higher, or $3,016 more per year (Rosenfeld, Denice, and Laird 2016; Denice and Rosenfeld 2018).17 Consequently, estimates of the impact of eroded collective bargaining on wage inequality that incorporate union spillover impacts find a larger role of the impact of unions on wage inequality. For instance, Western and Rosenfeld (2011, Table 2 and analyzed in Mishel et al. 2012, Table 4.38) find that the weakening of collective bargaining explains a third of the increase in male wage inequality and a fifth of the rise of wage inequality among women over the 1973–2007 period. Such research demonstrates that the erosion of collective bargaining has been the largest single factor driving a wedge between middle- and high-wage male workers, which, as established above, is the main dimension of wage inequality that grew among men other than the soaring of earnings for the top 1% (keep in mind that the wage gap between middle- and low-wage men has not grown).

The most recent research provides a more up-to-date analysis that incorporates a spillover impact and provides additional insight because the results directly report on the impact of eroded collective bargaining on the wage gap between high-wage (90th percentile) and middle-wage (50th percentile) workers by gender. These results from Fortin, Lemieux, and Lloyd (2021) are shown in Table 1.

The erosion of unions (column 3) can explain from 28.8% to 36.7% of the growth of male wage inequality as measured, respectively, by the standard deviation of log wages and the Gini coefficient. The most salient finding is that eroded unionization explains 37.3% of the growth of the 90/50 wage gap over the 1979–2017 period. As discussed earlier, this is the only source of growing wage inequality among men in the bottom 90% of earners. Fortin, Lemieux, and Lloyd (2021) show a smaller impact of eroded unions on women’s wage inequality; the erosion explains 6.7% to 8.8% of the growth of women’s wage inequality as measured by the standard deviation of log wages and the Gini coefficient and only 13.0% of the growth of the 90/50 wage gap.

Using an (unpublished) analysis by Thomas Lemieux, who relied on the model in Fortin, Lemieux, and Lloyd (2021), we can examine the impact of deunionization on the median and the 90th percentile wages for men and women combined over the 1979–2017 period. Deunionization raised the log 90/50 wage gap by 7.7 log points, almost entirely by reducing the median hourly wage by 7.6 log points, or by 7.9% (0.2% annually). The impact on men alone is larger, with deunionization lowering the male median wage by 10.9 log points, or 11.6% (0.29% annually). Deunionization therefore explains 33.1% of the 23.2 log point growth of the 90/50 wage gap over the 1979–2017 period.

The Fortin, Lemieux, and Lloyd (2021) results are very comparable to those of Stansbury and Summers (2020). In particular, we have benchmarked the Fortin, Lemieux, and Lloyd estimates of the impact of deunionization on the median wage with the estimate of Stansbury and Summers of the impact on the non-college-educated wage. Once one aligns the time periods, one finds that the Stansbury and Summers estimate is even larger.18 The Fortin, Lemieux, and Lloyd results for how much deunionization explains the growth of wage inequality also align with those by Western and Rosenfeld (2011).19

Newly developed historical data from the early postwar period affirm that collective bargaining was a strong force for greater equality of wages. For instance, Callaway and Collins (2017), using data from a survey of men living in Philadelphia; New Haven, Conn.; Chicago; St. Paul, Minn.; San Francisco; and Los Angeles in 1951, found “the wage premium was larger at the bottom of the income distribution than at the middle or higher, larger for African Americans than for whites, and larger for those with low levels of education,” findings that are “consistent with the view that unions substantially narrowed urban wage inequality at mid-century.” It follows, of course, that the consequent erosion of collective bargaining would increase wage inequality and have the most adverse impact on nonwhite workers, those with the least education, and low- and moderate-wage workers.

Likewise, Farber et al. (2021, 33), who developed data on union households from Gallup surveys going back to 1936, find that “mid-century unions a powerful force for equalizing the income distribution.” This happened because unions disproportionately represented “disadvantaged” workers (nonwhite or less educated), raised the wages of low- and moderate-wage workers the most, and had a large, stable impact of raising wages for union workers by roughly 15–20 log points over the last 80 years.20

Some pundits and analysts, skeptical about the impact of weaker unions on wages or wage inequality, claim that the decline of unions reflects a decline in worker interest in unions or is due to globalization and automation, i.e., endogenous factors. Neither objection is well founded.

Kochan et al. (2018) examined the level of interest in joining a union among unorganized workers and found that the “demand for unions” has risen substantially since the late 1970s. Kochan and Kimball (2019) described these results as

differences in the percentage of non-union workers who indicated a preference for union representation in nationally representative surveys in 1977, 1995, and 2017. Note that the 1977 and 1995 results were nearly identical: approximately one third of the non-union workforce indicated they would vote to have union representation if given an opportunity to do so on their current job. In 2017 that number increased to 48 percent. This number translates into an under-representation of unions of approximately 58 million workers.

Mishel, Rhinehart, and Windham (2020) assess the endogeneity of union decline and find that manufacturing employment decline can account for only a small part of it, perhaps 15–20%. Ongoing automation of manufacturing and globalization surely contributed to the shrinkage of manufacturing employment and the loss of union jobs in manufacturing, but the authors point out that the share of workers covered by collective bargaining declined strongly across the private sector in sectors not heavily affected by globalization, including construction, transportation, communications, utilities, supermarkets, hotels, and mining. So, any focus limited to manufacturing will not capture the full picture. Moreover, the erosion of unions in manufacturing is not due only to automation and globalization.

An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD 2019b) analysis of the cross-country decline in collective bargaining across advanced nations found:

Contrary to a commonly held belief, the combined contributions of demographic changes and structural shifts, such as the shrinking of the manufacturing sector, are small and leave most of this declining trend [in collective bargaining] unexplained.