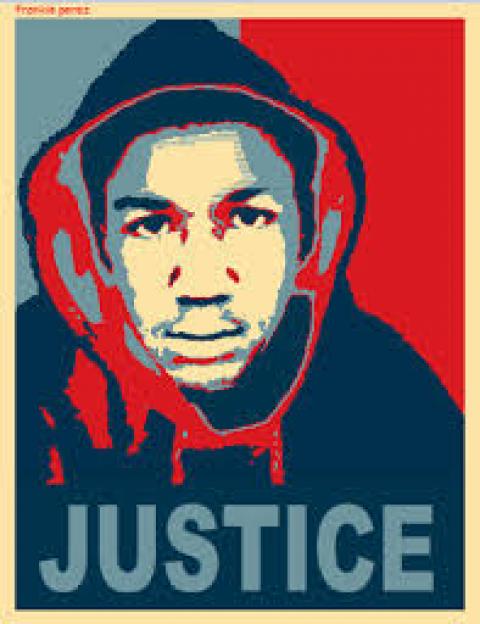

On February 26, 2012, 28-year-old George Zimmerman shot and killed an unarmed 17-year-old African American teenager who, after buying Skittles and iced tea at the local 7-Eleven, was on his way home. Zimmerman claimed he was acting in self-defense, and the Sanford, Florida police force, after a brief investigation, refused to press charges. Following several months of demonstrations, Florida Governor Rick Scott (no fan of anthropology, as you may recall) assigned the case to State Attorney Angela Corey, who charged Zimmerman with 2nd degree murder. A year and a half after the killing, on July 13, 2013, a virtually all-white (and all-female) jury found George Zimmerman not guilty of murdering Trayvon Martin (see journalist Charles Blow for an excellent discussion of the systemic racism that brought us to this moment). Though prosecutors, many journalists and large segments of the public saw the case as a quintessential example of race profiling - there is ample evidence, many believed, that Zimmerman profiled the teenager because he was a young Black man - during and after the trial both teams of lawyers and the jurors tripped over themselves proclaiming that neither the murder nor the subsequent not guilty verdict had anything to do with race. How do we explain these startlingly different responses as to the role of race?

As a discipline, anthropology has a special relationship to race - the concept that figured so strongly in the Trayvon Martin case and, as I wrote in a 2005 article in the Annual Review of Anthropology, a conflicted history with respect to race and racism. Anthropology is the discipline that fostered and nurtured "scientific racism," a world view that transforms certain perceived differences into genetically determined inequality and provides a rationale for slavery, colonialism, segregation, eugenics, and terror. Our discipline also has a significant tradition of anti-racism that emerged from the tumult leading to World War II.

Color-Blind/Post-Racial Racism: Denial

In the United States, after more than 200 years of slavery and 100 years of legal segregation, the Black Freedom Struggle culminated in the Civil Rights Movement and resulted in significant victories. "Whites-only" signs are gone, antidiscrimination laws have prohibited overt forms of discrimination, and we have elected a Black president. However, other means of exclusion support residential and educational segregation; voting is made increasingly difficult because of gerrymandering, voter identification requirements, and most recently the Supreme Court's gutting of the Voting Rights Act. As well, the criminal justice system remains stunningly unjust - a phenomenon aptly named "the new Jim Crow" by Michelle Alexander.

What has changed is that these inequalities are no longer explained in terms of the racist structures and practices that produce them; indeed the existence of racism is denied. We now live in what has been termed a post-racial age, with new ideologies of racism, such as "color blindness." As sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva explains, the essence of the new "color-blind" racism is that "racial inequality is explained in terms of nonracial dynamics." In other words, flagrant forms of racism coexist with the denial of racism. It is therefore not surprising that at the press conference following the announcement of the verdict, Zimmerman's defense lawyer, Mark O'Mara, not only denied that the case was about race, but, when asked whether the outcome of the case might have been different if Zimmerman had been a 17-year-old African American teenager with a gun who followed and shot a 29-year-old white man walking home in the rain, O'Mara responded that if Zimmerman had been Black, "he would never have been charged with the crime." Even Michael Steele, former chairman of the Republican Party and an African American man, was moved to ask, "Is he high?" Importantly, the ideological framework of color blindness not only rationalizes racial inequality; it also serves to erase and delegitimize antiracist activities. Hence O'Mara also felt free to attack the Civil Rights activists who called for the investigation that finally led to the trial.

Anthropology, Race and Racism

In the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, cultural anthropologists in particular have understood race to be a social construction - not a biological given (indeed, this is almost a mantra). Race is constructed in the sense that racial hierarchies are created at specific historical moments, frequently linked to labor exploitation, conquest, nation-building, and racialized definitions of citizenship. The racial projects that create the hierarchies are historically contingent, mutable, and at once structural and dynamic. Although the American Anthropological Association's Race: Are We So Different? initiative has made a major contribution to addressing the racial ideologies of the world that anthropologists helped to make, what we have not always done so well is to demonstrate that though race is socially constructed, racism is a lethal social reality, constraining the potential, if not threatening the lives, of millions of people.

Given the major role anthropology played in the earlier elaboration of race as a "scientific" category, the Trayvon Martin tragedy should provide an opportunity for reflection on our discipline, our association, and our scholarship. Anthropologist Karen Brodkin correctly points out that many anthropologists have become race-avoidant in their practices, in their workplaces, and in the association, unfortunately and perhaps unknowingly reinforcing racism by ignoring or denying it. In 2007, former AAA President Alan Goodman created a Commission on Race and Racism within Anthropology and the AAA. The commission's findings about practices in many anthropology departments were, to say the least, discouraging. Anthropology is one of the least integrated disciplines. The commission found that sister organizations, including the American Sociological Association, the American Psychological Association, and even the American Economics Association and the American Political Science Association had more robust, proactive and aggressive strategies to retain and attract scholars of color. The AAA Committee on Minority Issues in Anthropology, initially created in 1993 as an outcome of the Commission on Minority Issues, is the only association-wide committee charged with addressing the recruitment and retention of scholars of color. It has had a troubled history, despite the best efforts of able chairs and the support of several presidents. In its most recent iteration, the committee's expanding charge and composition has evolved in such a way that anti-racism has not always been seen as a predominant concern. Sadly, this and the failure of other initiatives are in part due to the association's reluctance, despite good intentions, to recognize, confront and act on racism.

Diversity has become a threadbare term used throughout the academy and the workplace to refer to almost any type of variation. Expanding diversity is admirable but does not in itself address the historical injustices of racial exclusion. To the extent that it substitutes for antiracist affirmative action, or underplays the US history of creating a hierarchy of racialized populations, emphasis on diversity obscures the systemic character of racism in the United States. All forms of discrimination are lamentable, but they are not equal nor even necessarily comparable, and often require different interventions. To lump the issue of all differences together and to expect a committee or any other body to address all inequalities is to guarantee failure, which then serves to support the view that the problem is intractable. The events of the Martin case underscore the importance of reestablishing anti-racism as CMIA's primary aim and working more systematically to address racism in our discipline, association, workplace and the academy.

The Task Force on Race and Racism

In November 2012 I appointed a Task Force on Race and Racism, co-chaired by Karen Brodkin and Raymond Codrington. The Task Force set itself three modest priorities for the year: (1) to construct a website that is at least on par with those of our sister disciplines; (2) to hold a roundtable at AAA meetings to promote a discussion of recruitment and retention of racialized anthropologists in the subfields, particularly archaeology and biological anthropology, where they are woefully underrepresented; and (3) to administer a survey to the membership that could produce baseline data on both representation and the racial climate. This third priority is perhaps one of the more controversial initiatives; some of our members are understandably offended about being asked about their racial/ethnic identity. Task force members are well aware that individuals have many identities, but also know that, as anthropologist Lee Baker put it, there is a difference between identity and identification. In whatever ways Trayvon Martin may have conceived of his identity, it was how George Zimmerman identified him, supported by a structure of racism that led to his death. Those who suggest that concern about racism is a misplaced concern of the previous generation would do well to remember that Trayvon Martin was only 17 years old.

Needless to say, the problems of race in our association pale in comparison to the loss of a young life - but it would be a mistake to imagine that they are wholly disconnected. Those of us who research race, racism and inequality must continue to name racism without sugarcoating it; to analyze the ways in which racism is maintained and produced inside and outside of our discipline without overtly targeting its victims; and to use the tools of anthropology to identify the underlying social relationships and informal workings of racist projects. Most important, we need to interrogate the new hidden forms of structural racism and deconstruct, in the best sense of the word, the ways in which racism expresses itself in the age of "post-racial color blindness." In this way, we do our best to honor the memory of those, such as Trayvon Martin, who have paid the ultimate price for racism.

[Leith Mullings is the president of the American Anthropological Association.]

[Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.]

Spread the word