A Louisville Union Built its Strength as Blacks, Whites Took on International Harvester

They crop up right around now, along with the ads for mattress sales: the annual assessments of the state of the American labor movement. There will be a certain mournful sameness to these Labor Day reflections.

While wages stagnate and inequality escalates, union membership rates continue plunging.

The Trump Administration and the Republican-controlled Congress are not, to put it mildly, looking to reverse that trend.

“Right-to-work” is now the rule in most states, as Kentucky and Missouri passed such legislation earlier this year.

And just a few weeks ago, the high-profile organizing effort at Nissan’s Mississippi plant ended in failure.

If you’re a union supporter, all that might well put a damper on your backyard barbecue.

Inevitably, these analyses will focus on the American South. They’ll note the region’s lack of union tradition, the chronically sub-par standard of living, the toxic division sown by racism. The Mason-Dixon line serves as firewall, sustaining an employer-safe zone that undermines organized labor’s ability to secure a firm foothold anywhere else. This deeply-rooted reality makes it hard, these days, to envision how working people can unite to challenge corporate power.

Except that not too long ago, and right here in Louisville, a different story was being written.

“We’re not going to be second-class citizens in the South.” That’s what the 2,000 workers at the sprawling new International Harvester factory — which once stood where planes now take off from Standiford Field — declared in 1947. They objected to the lower pay scale that Harvester management had imposed, and to underscore their point, they walked out of the plant. They then kept it shut down tight in a raucous strike that dominated Louisville’s headlines for over 40 days.

What made this action run contrary to much conventional wisdom is that Harvester’s wages were generous by Southern standards. And nearly all of those who walked out had never been in a union before. And during the strike, whites and African-Americans demonstrated a level of solidarity unprecedented in then heavily-segregated Louisville. And one more thing made the “Southern differential” strike of 1947 noteworthy, then and now: With only $61 in their local union’s treasury, the workers took on one of the world’s most powerful corporations — and won.

Industrial empire built on anti-unionism

International Harvester ceased to exist in the mid-1980s, so it bears reminding that it was one of America’s original industrial empires. Cyrus McCormick began production of his namesake reaper in Chicago before the Civil War and soon became one of the nation’s richest men; in 1902 the company — which the McCormick family continued to control — morphed into International Harvester, a farm equipment monopoly employing hundreds of thousands. IH was a global enterprise well before “globalism” became common parlance, with factories, mines and mills scattered from Australia to Russia to Benham, Kentucky (a coal operation and company town Harvester built and owned in its entirety).

But from its early days the company also garnered a reputation for something else: anti-unionism.

Police violence during a strike outside the McCormick factory triggered the 1886 protest at Chicago’s Haymarket Square, which devolved into chaos when a bomb suddenly exploded. In the aftermath four anarchists were hanged and the eight-hour movement died with them. Cyrus McCormick II played a prominent role in securing both outcomes.

In the early 20th century, IH pioneered in the new field of industrial relations, developing more sophisticated methods to quash workers’ organizing efforts. Consequently, even with the upsurge of activism in the Great Depression, International Harvester remained union-free, holding out even after behemoths such as General Motors, Ford, Republic Steel and General Electric had succumbed. It was not until 1941 that Harvester president Fowler McCormick (grandson of both Cyrus McCormick I and John D. Rockefeller) finally signed a multi-plant contract. By the end of World War II, Harvester’s many manufacturing operations — all of them located in the Midwest or Northeast — were at long last unionized.

No surprise, then, that the union that broke through at IH was bold and unflinching. The Farm Equipment Workers, known as FE, was officially formed in 1938; it was one of the founding unions in the Congress of Industrial Organizations — the CIO. It was never a very big operation but garnered an outsized reputation for its militancy, with many of its key leaders connected to the Communist Party. “The philosophy of our union,” an FE official explained, “was that management had no right to exist.” In practice, this meant, among other things, a preference for addressing workers’ complaints at once, instead of adjudicating them through a grievance procedure; plants represented by the FE thus registered exceptionally high levels of walkouts between contracts. It, then, was at the least ironic, and perhaps constituted some measure of poetic justice, that historically anti-union IH would find itself saddled with the relentlessly radical FE.

So, as Fowler McCormick planned his company’s postwar expansion, he looked to the largely nonunion and low-wage South. In 1946 IH purchased a former aircraft facility in Louisville and began retrofitting it to manufacture small Cub tractors. When it opened, all the employees were men, most quite young; a hefty percentage were recently-returned World War II veterans. The factory would become the largest in Kentucky, employing by the 1950s over 6,000 people — more than 15 percent of them African-American, as IH applied its equal opportunity policy to its Southern plant — and was once the biggest tractor production facility in the world.

But Harvester did not achieve all it had hoped for in its move South: In July 1947, FE Local 236 secured bargaining rights at the Louisville plant.

‘Hell, a Negro couldn’t even look at a machine’

The leaders of this new local, said FE literature, believed in “something hitherto almost unknown in Louisville — their policy of militant trade-unionism, their conviction that once the Negro and white workers were united, the low-wage system of the South would collapse.” Its president was hard-charging, hard-drinking and politically radical Chuck Gibson, a white worker from the assembly department. Fred Marrero, already known in Louisville as an outspoken African-American activist, was the Local’s Secretary-Treasurer. African-Americans Sterling Neal and Jim Wright were also key leaders. And the FE staffer assigned to Louisville was Bud James, a patrician-turned-firebrand, who’d abandoned his University of Chicago education first to join the Communist Party and then to sign on as an FE organizer. Within this group, the oldest was in his early 30s and all but Neal had seen active combat during World War II.

As their first undertaking, they decided to challenge International Harvester over the very reason the company had come to Kentucky in the first place.

Harvester claimed a “belief in Louisville and its future” brought it to town, but Local 236 insisted the company was instead drawn by “bright dreams of cheap Southern labor.” Wages “are set in accordance with the generally prevailing rates in a given community,” so Harvester said to defend its Louisville pay scale, the lowest at any IH factory.

It was this “Southern differential” that Local 236 leaders vowed to eliminate.

But before taking on management, they first needed to convince the Louisville workforce that they were owed more than they were being offered. Initially, it was a tough sell. Harvester’s wages were at least as good as those paid by nearby employers, and for blacks, in particular, the plant promised opportunities unavailable elsewhere. Jim Wright remembers that even he had to be persuaded at first:

“To the common guy on the street, that got a job at Harvester, well, you’d think he’d gone to heaven. They give those guys jobs, give them a machine — hell, a Negro couldn’t even look at a machine nowhere, wouldn’t even let him clean it up — and here they were running it, had all these benefits, and things. If a guy in Indianapolis, or someplace like that, doing the same job like I was on, and I was getting 35 cents an hour less than he was getting, I used to think that was all right …”

Yet the Local 236 leadership hammered away at the differential.

“We make the same tractors [Harvester] sells to the same farmers; they don’t sell a Southern tractor one penny cheaper than they sell another tractor,” Sterling Neal said, recalling the arguments they used. “We’re not going to be second-class citizens in the South.”

To prevail on this point, Local 236 leaders insisted that racial unity was essential. FE literature emphasized that “the Southern bosses for generations had played Negro against white, and white against Negro” and insisted “there was a direct connection between that and the fact that Southern workers were the lowest paid in the country.”

Given the characteristics of the workforce — the vast majority white, many from outside Louisville — Jim Wright was not sure this would prove a winning argument. “We had hillbillies, that’s all we had,” he said. “Farmers. Guys who wore overalls. Chewed tobacco, spitting on the floor. And those kind of guys were racist — I mean real racist.”

FE leaders in Louisville hoped they had convinced workers, both black and white, to challenge their status as “second-class citizens” within the Harvester empire. It was nonetheless a gamble when, on Sept. 17, 1947, a union contingent went to the front office with petitions calling for the elimination of the “Southern differential.” But when the plant manager refused to discuss the matter, “a lot of the workers spontaneously began to shout, ‘Let’s hit the bricks,’” Sterling Neal recalled.

“It wasn’t started as a strike — it was merely a demonstration in the shop,” Bud James said, adding, however, “the guys were so startled by seeing their own strength that they pulled out together” and the plant emptied out. The Local didn’t have a union hall yet, so James scrambled to find one; FE leaders were also uncertain whether their walkout was legal — especially because a new law, the Taft-Hartley Act, had just been passed — so they dubbed it “a continuous meeting.” And they didn’t even have a membership roster or a list of employees, so the day after the strike began they put out a call for workers to come by the new union hall in downtown Louisville to sign up for picket duty — or rather, register as “meeting notifiers” — figuring that way they’d be able to collect some names. The response stunned even the leadership, as James recalled:

“Well, the next day something like 2,000 people showed up, and there was a double line, and the girls at the typewriters spent the whole day giving them their slips and their duties. This double line stretched out into the hall, down the stairs and onto the sidewalk and clear around the block. They waited all day in line to register for that strike. I’ll never forget that line.”

Arrests did not stop strikers

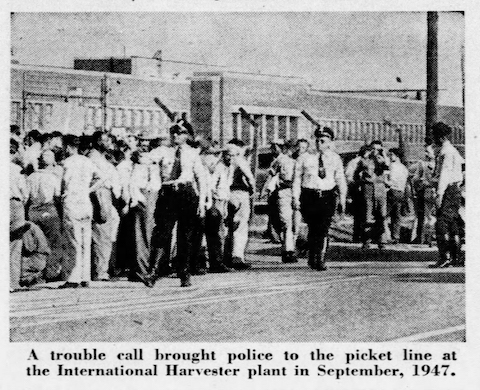

With this early demonstration of enthusiasm, the walkout became what Jim Wright called “a humdinger.” Production was entirely halted at the plant, as sizable picket lines patrolled the gates, at first turning back even management personnel. This was too much for Harvester to accept; “unlawfully and by force,” the company argued in court, Local 236 had effected “a seizure of the Louisville Works [which] resulted in the denial to Harvester of access to its own property except by permission of the union.” Ten days into the walkout, IH got the injunction it sought, limiting to two the number of strikers at any of the plant’s six entrances.

This didn’t change things much, however, as Chuck Gibson seized on the fact that the order omitted any mention of how often substitutions were allowed. “Nothing can prevent you from replacing a fellow worker every 30 seconds,” Gibson told the Local’s members, and so they still congregated near the plant — sometimes over 1,000 strong — waiting to take their turn on the line. Since the surrounding area was then largely vacant countryside, the police tolerated the throngs, so long as they “stood away from the gates.”

But they frequently pressed too close. In one two-day stretch in October, for instance, 30 union members, both black and white — including Chuck Gibson, Bud James, Fred Marrero and Jim Wright — were arrested for various forms of picket-line misconduct. Gibson was charged with overturning a plant foreman’s car — while the foreman was still in it. Once out on bail, they went back at it again: James was hauled in at least six times during the strike. Though Harvester invited employees to return, few did; the union claimed only a few dozen white workers, and no African-Americans, crossed the picket line.

“In Louisville there hadn’t been a successful strike in an industry,” Sterling Neal indicated, “since anybody could remember … it wasn’t like Detroit or Chicago or Pittsburgh, or someplace where shops had been shut down. It just had never been done here.” Yet the Local’s rank-and-file took easily to aggressive, and creative, labor activism. One morning, 800 World War II veterans in the Local, wearing their old uniforms, paraded around the plant, led by an African-American, former Marine sergeant. On another occasion, they parked their cars, three abreast, on the street leading to the plant; traffic was gridlocked as the union conducted a meeting in the middle of the road.

The FE also appealed to the broader public, insisting that “Harvester is not being a good citizen of this community.” The differential enriched the company and the McCormicks, while Louisville workers “can afford to buy less consumer goods, less services, less of what the farmer produces.” On their lone hand-operated mimeograph machine, Neal said, “we ran off about 10,000 handbills a day” and union members “went out into the street corners and left the stuff all over town.”

Some material was distributed even farther afield. “Quite a few of the boys had relatives all around through what we call Kentuckiana, between here and Indianapolis and as far South as the Tennessee line, and those fellows making the trips over the weekend while we were on strike, they’d take a lot of those handbills and they’d leave them off in these little hamlets [and] the general stores,” Neal recalled. Strikers’ wives, as well, visiting “scores of rural communities” helped circulate fliers pointing out to small farmers — the IH Cub’s customer base — “that they would not get the tractor any cheaper if the tractor was made in Louisville but still the company wanted to pay a cheaper wage.”

Black and white on the picket lines

This activity transformed the Local’s membership. “Everybody was cutting everybody’s throat in this area,” Sterling Neal said of race relations among workers, and thus outside the FE “everyone was sure we were going to lose” when the strike began. “This is a Southern town, and the thinking of the guys is Southern,” Neal said. “But one thing that happened during that strike: The fellows met together in the hall, they ate together, they picketed together and they practically lived together down in the hall, which was an unusual thing … it was the first strike in Louisville when Negro and white guys were really out on the picket lines battling together.” As a result, Jim Wright said, the 1947 walkout “unified the people” in nascent Local 236.

International Harvester, of course, made its own appeals during the walkout. In late October, Harvester sent a letter to all its employees represented by the FE, decrying the “situation” in Louisville. “The Company wants good relations with responsible unions,” but with the FE that was impossible, the letter said, since its officials were “irresponsible radicals.” The letter concluded with this advice to the FE membership: “Get yourself some new leaders.”

Those “irresponsible radicals” in the union’s top leadership responded by threatening to pull all 35,000 Harvester workers in the FE out on strike, because the “precedent in Louisville” would allow the company “to cut wages … throughout the chain.”

Harvester capitulated, granting hefty wage increases to end the walkout. On Oct. 27, the members of Local 236 returned to work with “two smashing victories in hand,” so said the FE News, “one over International Harvester, the other over the Mason-Dixon, low-wage line.”

‘A religious feeling of them sticking together’

The “Southern differential” fight was over, but its lessons reverberated. Local 236 waged “a constant campaign” about racial solidarity, said civil rights leader Anne Braden, who began working with the FE in 1948.

“I never went to a meeting that somebody didn’t get up and make a speech about the reason we’re so strong and we can win — and they always said that they had the highest wages in the South, and I never saw that refuted anywhere. The reason we’ve got all that is because we stick together, black and white. They attack a black worker, and we’re there to do something. We’re going to walk out of that plant — this is the reason we’ve got the strong union. And they preached that constantly.”

This “constant campaign” carried into the community as well, with Local 236 at the forefront of battles in the late 1940s and early 1950s to desegregate Louisville. But to Jim Wright, perhaps the FE’s biggest impact came at the personal level, as those whites who had come into the Harvester plant as “real racists” became friends with black workers there.

“They’d go along with [blacks], eat with them, go places with them, go hunting with them, walk out with them, work on a machine with them, have fun in the shop with them. That was a new thing for [the white workers]. That union had put what people call some kind of religious — I don’t mean a biblical religion — I mean a religious feeling of them sticking together.”

But the militant FE, beset not just by International Harvester but the labor establishment too — was declared “communist-dominated” and expelled from the CIO in 1949. It was unable to survive. In 1955, the FE merged into the much larger United Auto Workers.

So the union and the company are both long gone. But something remarkable happened at the plant that once stood on Crittenden Drive: Black and white workers there decided that none of them should be “second-class citizens,” and fighting together, they got what they deserved.

On this Labor Day in particular, that’s worth remembering. •

Toni Gilpin, a labor historian, is working on a book about the Farm Equipment Workers union, entitled “The Long Deep Grudge: An Epic Clash Between Big Capital and Radical Labor in the American Heartland.”

Spread the word